Selecting The Right Talent for Digital Transformation in FSIs

Also in this issue: What Many FSIs Get Wrong About Agile/Scrum Roles, Other FSI Digital Transformation Weekly Reads

Selecting The Right Talent for Digital Transformation in FSIs

"HR needs to step up its game and get us stronger talent," lamented one of the LOB Heads at the executive offsite. The FSI asked me to facilitate a C-Suite workshop as they embarked on a risky digital transformation journey. When I inquired about the number of employees who had previously worked for advanced competitors or digital native companies, the same executive responded, "We have 10-15 such employees already, but despite having 30 open requisitions, we haven't been able to find suitable candidates." He then glanced at the head of HR across the room as the reason for this miss.

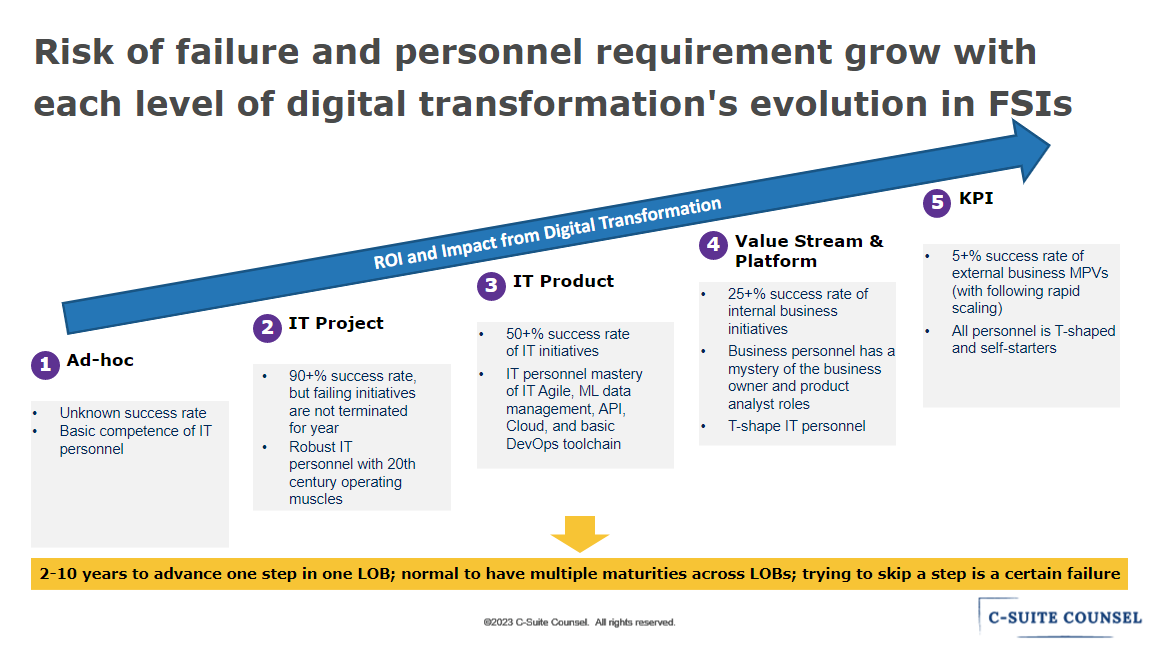

As we discussed in another newsletter, digital transformation centers around personal change for executives who are aiming at significant upgrades in their respective areas of responsibility. This aspect is often the most challenging, as many FSI executives tend to prioritize cool technology and internal politics, hoping that these factors alone will be sufficient. However, for those with the courage to embrace it, we discussed a five-step approach (outlined below) that starts with tactical hands-on activities that an FSI executive may not have engaged in for some time.

With those activities underway, an FSI executive faces the challenge of selecting the right talent within a suboptimal context:

The executive usually lacks experience in what good looks like at the next level of digital transformation.

Existing employees are unlikely to come from more advanced firms.

There is a general corporate pressure to provide new opportunities for all employees.

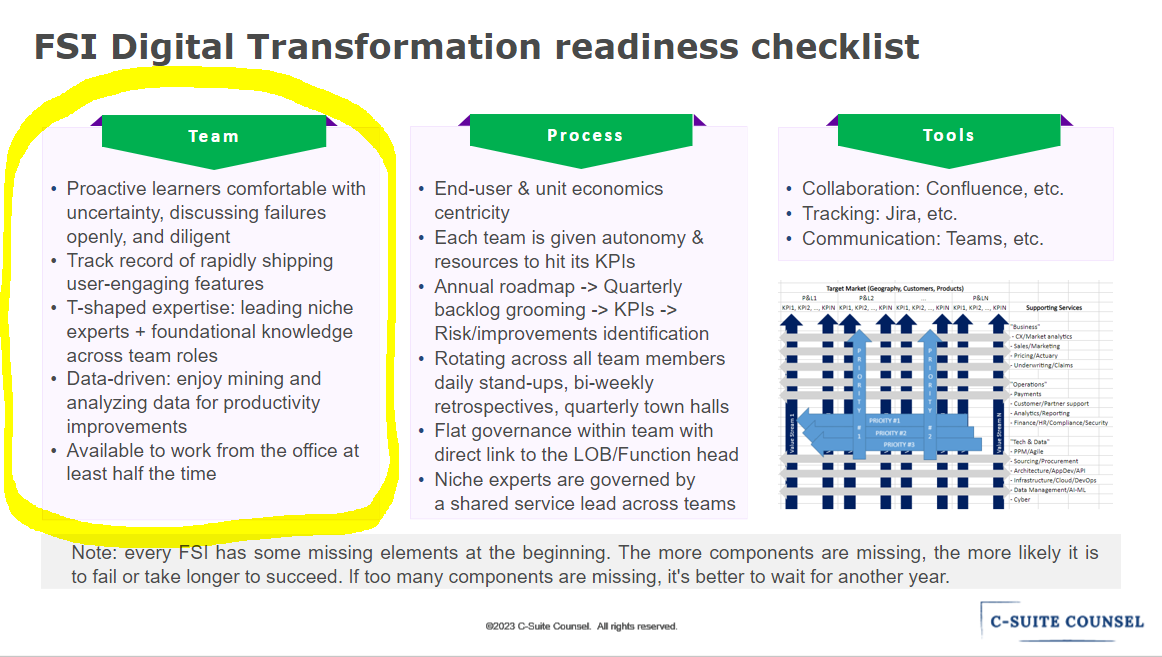

That is why offering employees the opportunity to self-select into a challenging journey (Step 3 on the slide above) is the only viable approach. Similar to a forced marriage, an involuntary assignment would result in a miserable experience for all parties involved. However, it is important to note that employee willingness alone is not sufficient. Digital transformation is a highly complex process that may not come naturally to many employees in a less mature FSI. In other words, many employees may have a blind spot - they believe they can level up when, in reality, they may not be capable of doing so. An FSI executive could utilize the checklist below to ensure that each team member embarking on a digital transformation journey possesses, to some degree, the majority of the following attributes (see image):

In my experience, the above steps would fulfill approximately half of an FSI executive's initial talent requirements. Note that with each phase of digital transformation the risk of failure increases by design, and the expectations placed on each participant become more challenging and distinct. This is the essence of true 'transformation’. For instance, even highly skilled project managers who excel in handling complex waterfall projects may face difficulties transitioning into the role of an IT product lead. Similarly, proficient product leads might struggle when tasked with leading value streams or platform teams.

While irrelevant in terms of the nearest future, the ultimate talent vision is a level of effectiveness that exceeds the typical FSI employee by a factor of '10X’, as seen in the best fintechs. This superiority does not necessarily stem from generating more output, but rather from possessing learned playbooks to prioritize high-impact activities and avoid engaging in low-value ones. This was exemplified by Elon Musk who managed to accelerate Twitter's evolution with 90% fewer employees. When a firm predominantly consists of '10X' employees, it becomes apparent that only a fraction of the workforce is truly necessary, while the rest inadvertently obstruct progress.

Obtaining half of the talent needs from the existing pool of employees is a commendable beginning. However, it does not address the lack of practical knowledge of executing at the next level of digital maturity. To prevent endless debates and the adoption of ineffective practices, the initial squad must consist of a critical mass of talent who possess a clear understanding of what good looks like at that next level. Otherwise, it would be akin to the blind leading the deaf.

And that is where many FSI executives make three mistakes: they settle for ill-suited employees, engage Agile trainers without a proven operating track record, and delegate the task of sourcing stronger talent solely to HR/Recruiting.

The first mistake is particularly unfortunate as it leads to both the executive and a team member experiencing up to three years of mutual disappointment before the inevitable termination. It never fails to astonish me how often FSI executives, who themselves are a good fit for their roles, continue to retain employees who are not. Instead of taking the necessary action of terminating the ill-suited employee, they persist in complaining to me and others about the employee's lack of progress. Meanwhile, the employee becomes increasingly aware that they are falling short of expectations and naturally places the blame on the executive for not providing clear requirements and hands-on guidance.

The right Agile trainer could add significant value while the wrong one would create lasting damage. I always ask clients who claim to have mastered Agile to let me spend an hour with their best Agile team. One such large life insurance firm agreed to let me observe three such teams. What I saw was quite ineffective, so I asked them where they learned Agile. “We have a 20-people Agile coaching group.” Meeting with that group, they honestly acknowledged that they got certified in Agile and began training employees without ever personally building digital products.

Finally, HR/Recruiting is unlikely to get the right talent by themselves. Even if a recruiter used to work in a digital native firm, finding the candidate with just the right digital maturity requires operational expertise. Plus, most of the right candidates wouldn’t be interested in joining a less mature firm. A typical recruiting outreach is likely to be an additional turnoff for them.

Instead, an FSI executive should take full ownership of the sourcing process, including identifying suitable candidates and overseeing a high-quality interviewing workflow. This involves personally posting on platforms like LinkedIn and Twitter, proactively reaching out to potential candidates, and participating in local digital meetups. The encouraging news is that approximately half of the candidates respond positively to such personal outreach from an FSI executive, compared to less than 10% responding to a recruiter. Within this candidate pool, around half may not be immediately interested, only a few may be ready for full-time positions, while others would consider temporary-to-permanent arrangements.

Successful FSIs typically assemble their initial squads using around half of their existing employees, 10-20% of new hires, and 30-40% of contractors (avoiding reliance on consultants or outsourcers for developing new operating muscles). As a consistent pattern with digital transformation, this substantial upfront investment by the FSI executive would generate significant long-term returns.

What Some FSIs Get Wrong About Agile/Scrum Roles

Agile has been present in FSIs for such a long time that it seems like everyone considers themselves an expert on the topic. And indeed, as we discussed in another newsletter, there haven't been any fundamentally new developments in Agile practices for at least a decade. However, some FSIs overlook a crucial aspect of Agile/Scrum roles - they are meant to be temporary. Just like permanent stand-alone heads of digital transformation should be avoided, the primary focus of Agile/Scrum specialists is to level up the permanent employees, rather than indefinitely performing the work on their behalf.

Instead, some FSIs are creating Agile bureaucracies of full-time coaches, team leads, and Agile executives who do not have primary operating responsibility. Consider this Agile Lead job description from a large FSI:

This FSI is clearly focused on developing the necessary operational capabilities for digital transformation, and the activities for leveling up make logical sense. However, this role should not exist as a standalone full-time position, and the concept of having an "agile coaching community" should be avoided. The success of the Agile/Scrum role is determined by how rapidly this person can level up others and become redundant. If an individual brought in to accelerate the transformation of this marketing group continues to carry out the same responsibilities even after six months, it indicates a lack of effectiveness in their role.

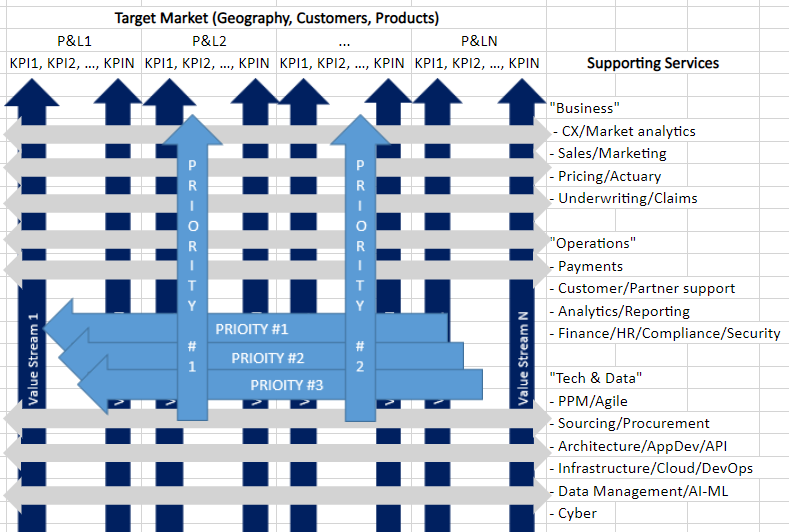

As we discussed in many newsletters, there are only two organization constructs in the target state of digital transformation: vertical value streams that make FSI money and shared services (platforms) that enable value stream at scale. For any Agile/Scrum role, it comes down to which area needs to transform next (e.g., Marketing) and how quickly that group could be leveled up to not require a full-time coach (3-6 months).

Some FSIs are uneasy with this approach as it involves a rapid and significant transformation of their operating model, plus, it requires hands-on executives. Instead, they opt for the presence of permanent Agile/Scrum intermediaries who serve as buffers. They act as a go-in-between among stakeholders who should ideally be working together directly without external coaching. Let's examine the job description of a Scrum Lead in such a role:

Again, while some of those activities are indeed necessary, it raises the question of why they are not being carried out by employees in the primary operating roles. In such cases, Agile/Scrum leads resemble the conventional project managers of the past century who would spend the majority of their time on tasks unrelated to project management itself.

The good news is that many FSIs, especially the advanced ones, have eliminated such permanent roles. They have followed the lead of fintech companies by assigning those responsibilities to the core team members while retaining traditional project manager titles for areas that still operate under a waterfall approach, such as Accounting. Yes, even the best fintechs utilize project managers instead of resorting to esoteric job titles like Agile or Scrum lead. Having well-defined and appropriate roles is a crucial requirement for achieving rapid transformation and organizational scalability.

If you're old enough, you probably remember the previous iteration of such permanent Agile/Scrum roles: Six Sigma Black Belts. These were similar full-time bureaucracies that created playbooks and offered coaching. However, at the end of each business cycle, such as in 2001 and 2008 in the US, FSIs would realize that these groups were providing little value and would eventually shut them down. The same fate is likely to befall these Agile/Scrum groups. Instead of waiting for that decision to be forced upon some FSIs, they could start transitioning these employees into operating roles or short-term contractor positions. Only if individuals can successfully level up one group within 3-6 months should they move on to the next, allowing these expensive overhead positions to have a chance at accelerating digital transformation.