Evolving Oversight of Software Development in Different Phases of Digital Transformation for FSIs

Also in this issue: At Times, Opting Against Digital Transformation in FSIs Is True Customer-Centricity

Evolving Oversight of Software Development in Different Phases of Digital Transformation for FSIs

Software development represents the most technical and potentially frustrating aspect of digital transformation. While many FSI executives can engage in conversations about technology architecture or database structures, very few truly grasp the essence of proficient coding. This might not have been a significant concern during the times when IT was seen as a cost center, or even more recently when IT was self-improving. However, as digital transformation expands across FSIs, software development increasingly becomes a business differentiator. Furthermore, in the ongoing digital arms race where FSIs allocate up to 20% of their revenue to digital transformation, the annual recruitment of hundreds or even thousands of software developers is becoming commonplace. How should FSI executives navigate this evolving landscape?

1. A Clear Path to Excelling in Software Development Oversight

The primary reason behind employee complaints concerning the bureaucratic culture within FSIs is the excess of a pure managerial class. While pep talks and career guidance do have value, the essential expectation from a manager is to offer a hands-on solution. This is typically not problematic during the initial phases of digital transformation, as a substantial portion of IT management is former front-line employees who often excelled as individual contributors. Steve Jobs advocated for this preferred method over hiring professional managers almost four decades ago:

Having the best software developers become managers out of necessity rather than choice might be an ideal scenario, but what should an FSI do when it doesn't have a sufficient number of top-notch software developers? Furthermore, the digital transformation of FSIs frequently demands proficiency in an entirely new category of software and more advanced software development skills. A scarcity of ideal talent naturally results in suboptimal hiring and inconsistent expertise among managers. While Steve Jobs might have been able to personally curate every Apple manager four decades ago, how can a typical executive measure and enhance the performance of software developers in a sizable FSI today?

2. What makes measuring the productivity of software developers so challenging?

The Head of Operations and Technology at a $60 billion revenue FSI felt confident in promising investors a $1 billion cost reduction. For software development alone, the company had over ten thousand highly paid employees whose work seemed to generate limited praise from the Business. Major outsourcing players were offering to absorb 80% of this workforce while enhancing productivity and reducing costs by 10-20%.

The outsourcing deal was signed, and the initial outcomes showed promise. The partner's staff was producing more code at a considerably lower cost per line. However, a few years later, the initiative was reversed, and the decision-maker was replaced. What went wrong? Given that the contract couldn't define the code's impact, focusing solely on volume and testing quality, the outsourcing partner assigned the task to their least experienced junior staff and instructed them to use generic software libraries. The resulting business functionality was quite rudimentary, prompting Business groups to start hiring their own "shadow" developers in order to create distinct code.

Even among leading digital natives, measuring software developer productivity remains a challenge. While it's simple to measure outputs like lines of code deployed per day or the number of software bugs, gauging the code's impact and scalability presents a quandary. Similar to a person’s speech, the same effect could be generated through various methods. The true brilliance lies in achieving the desired outcome in the most elegant manner. As Anton Chekhov said, "Brevity is the sister of talent."

3. McKinsey to the rescue

After forecasting the economic potential of generative AI in June 2023, McKinsey felt prepared to venture beyond an event horizon and delve into the enigma of software developer productivity. The esteemed consulting firm devised a playbook that, in trials with around 20 companies, yielded encouraging outcomes:

20 to 30 percent reduction in customer-reported product defects

20 percent improvement in employee experience scores

60-percentage-point improvement in customer satisfaction ratings

In typical McKinsey fashion, the playbook was founded on the amalgamation of best practices and the company’s own experiences:

Notice the lack of P&L impact, the main reason to pursue digital transformation. A significant proportion of McKinsey's clients find themselves in the earlier stages of digital transformation, lacking a clear method to gauge P&L impact at a team level (such as value stream or platform). As an alternative to assessing revenue impact, McKinsey suggests customer satisfaction, while velocity serves as their substitute for software development costs. The resultant metrics offer valuable insights, facilitating the prioritization of areas requiring further investigation. However, they fall short of revealing whether a team of software developers is generating a business impact with a substantial ROI.

The absence of North Star metrics is evident in two examples highlighted within the McKinsey publication:

One company found that its most talented developers were spending excessive time on noncoding activities such as design sessions or managing interdependencies across teams. In response, the company changed its operating model and clarified roles and responsibilities to enable those highest-value developers to do what they do best: code.

Another company, after discovering relatively low contribution from developers new to the organization, reexamined their onboarding and personal mentorship program.

Observe the focus on narrow functional expertise, which encompasses solely coding, as opposed to T-shaped profiles capable of spanning the entire software development cycle, including design and cross-team alignment. Similarly, there's an emphasis on improving the onboarding program instead of hiring robust talent who can make substantial contributions right from the outset.

4. What sets smart engineers apart from the wise ones?

As a McKinsey alum, I fully appreciate a process orientation and used to share a similar mindset. And it's not even McKinsey’s fault. Remember the first rule of capitalism? “Give customers what they want.” McKinsey serves the C-Suite, who typically are not interested in rolling up their sleeves and getting to know their best software developers. Blaming McKinsey for a top-down, process-oriented playbook is like blaming oil companies for global warming while driving around in an SUV for discretionary errands.

McKinsey responds to a demand from FSI executives who prefer to "manage" from their offices without transforming the operational model. For the typical FSI executive, process specialization for employees and refining existing processes fall within their comfort zone. Senior executives generally hold the belief that their years of experience render them superior in strategy, while the lower ranks should concentrate on optimizing execution. This evokes memories of simpler times in the 20th century, characterized by a command-and-control style with an emphasis on efficiency. This perspective also appears quite sensible to a McKinsey consultant who hasn't experienced scaling software products to capture market share.

The process-oriented approach to supervising software development, in lieu of a P&L impact, is suitable for organizations with low digital maturity. However, it would result in adverse outcomes for FSIs aspiring to be industry leaders. In such companies, top-down process orientation and smart engineers bring forth a notable risk, as explained by Elon Musk:

For an FSI to lead, it necessitates first-principle thinking. This involves the sagacity to devise a novel and elegant solution while competitors are preoccupied with refining conventional methods. This kind of wisdom although sounds self-evident, stems from deep thinking and firsthand expertise gleaned from practical experience in the field.

5. Mastering Software Development Oversight: Lessons from Top Fintechs

It's obvious that no executive possesses the wisdom to oversee every team's optimal software development process. Instead, for a leading FSI, it's imperative for the front-line team to be empowered to design their own process in alignment with their North Star metrics.

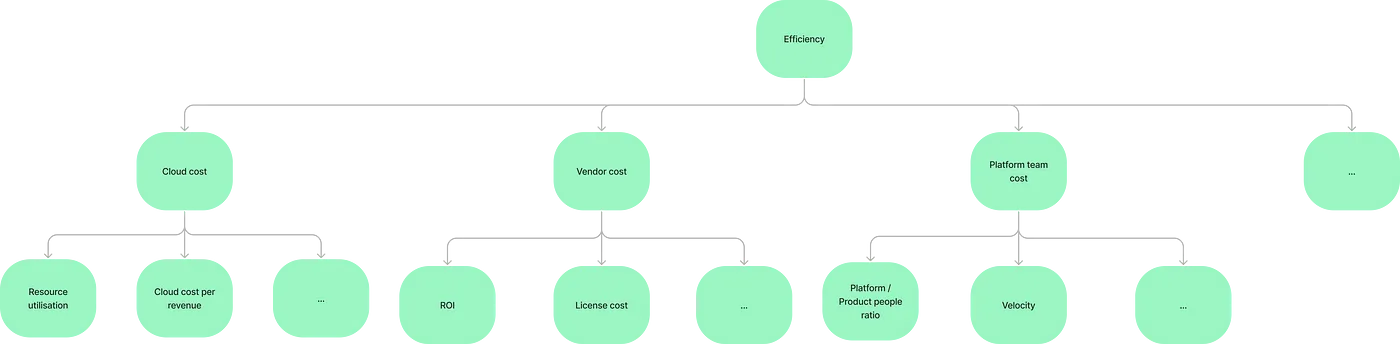

A leading fintech would have thousands of metrics related to the productivity of various teams, organized by KPI Trees. These metrics would naturally be accessible to everyone within the company via dashboards, and input from everyone would be readily welcomed. However, their primary purpose is for the team's consumption, rather than for executive oversight.

As often stated in our newsletters, digital transformation is a lengthy journey, and it's not anticipated that even a leading FSI could match the effectiveness of a top fintech within the next few years. Rather than adopting top-down metrics, every ambitious FSI could choose one or two software development teams to undergo a transformation in their oversight.

This might seem unconventional in comparison to the pragmatic McKinsey playbook. However, this embodies the essence of transformation: recognizing that your present operational strategies have been inadequate for a considerable period, and acknowledging a significant "blind spot" in your current mindset:

Digital transformation ← Personal transformation ← Acknowledging significant "blind spot"

How many FSI executives do you know who are willing to admit that they could have been much more effective in the last few years? Very few. A typical executive’s key priority is to get promoted or, at the very least, retain their job. Even if you present them with substantial evidence regarding their ineffective operating model compared to a proven approach, their response would likely involve questioning your data, your sources, and your biases. However, they won't readily "bridge" the gap; they won't delve into the intricate details, as it could lead to the uncomfortable realization of being mistaken.

If you happen to be among the minority of FSI executives who are open to embarking on a personal transformation journey, consider refraining from requesting more reports from your VPs and Directors. Instead, allocate the time you'd spend on reading and discussing reports to learn from your top developers. They represent the future of your FSI, and your primary emphasis should be on enhancing their effectiveness, not through top-down metrics, but through enablement and empowerment.

At Times, Opting Against Digital Transformation in FSIs Is True Customer-Centricity

Digital transformation should be justified solely by a P&L impact. Since transformation is very risky and costly, undertaking it only to reduce a cost base would rarely result in an attractive ROI. Increasing revenue would be a better approach, but it requires finding many customers willing to spend more. The good news is that despite the presence of thousands of FSIs in the US and a decade of well-funded fintechs, opportunities still exist to create billions in value.

Ramp, one of the finest fintechs we previously profiled, scaled to $300 million in revenue within just 3.5 years of its launch while securing a valuation of $6 billion. In 2019, Ramp identified a void in the value proposition for small businesses from card companies, particularly in aiding them to save. Card companies were leading clients into unnecessary expenditures through intricate rewards programs, and the management of expenses and oversight of spending lacked effective setups for tracking and identifying opportunities for savings. As is often the case, traditional FSIs hesitated to disrupt their well-established business models, creating an avenue for a disruptor to emerge, amplify the issues, and address the needs of dissatisfied customers.

While Ramp continues to experience 3-4X growth in its core product, it's reasonable to anticipate that the startup will eventually diversify its offerings to capture a significant portion of the small business banking relationship. In response, what strategies should traditional banks with a substantial customer base in this segment consider?

1. Are small business customers unhappy with their traditional banking solution?

According to the recent report from Cornerstone Advisors titled “Reinventing Business Checking: The Key to Growing SMB Relationships,” over 90% of small & medium businesses (SMBs) express a “somewhat-to-very” degree of satisfaction with their primary business checking account provider.

Furthermore, even if those SMBs opt to open a new account, digital capabilities would only be one of several factors and not the most critical one.

2. What are the customer segments among small businesses in relation to banking solutions?

As one would expect, Ramp initially attracted primarily small businesses from a similar startup segment. However, with its expanded size, it is now targeting all types of SMBs. Should larger banks or smaller ones be more concerned? While it might appear intuitive to suggest that smaller banks should hold a greater concern due to their lower digital maturity, it's essential to remember from the previous section that digital capabilities don't play a decisive role for small businesses when selecting a new banking relationship.

Furthermore, customers of smaller banks are self-selecting to stay in those banking relationships due to their distinct needs. As per the same report, these customers are twice as likely to write checks and have never borrowed from a digital lender:

3. To transform, or not to transform, should that be the question?

The Cornerstone Advisors report validates a counter-hype concept that digital transformation is not a universally mandatory endeavor. The varying degrees of digital maturity across different sectors of FSIs are not coincidental or due to complacency.

When a substantial unfulfilled customer need exists, it's more beneficial for FSIs to enter the arena rather than hoping that a disruptor won't emerge for a few more years. However, if customers are content and aren't shifting parts of their business to competitors, the sense of urgency diminishes. At times, being customer-centric means refraining from overwhelming your customers with digital features they don't require.