Continuous Learning as a Band-Aid for Digital Transformation in FSIs

Also in this issue: Should FSIs Buy or Build to Accelerate Digital Transformation?

Continuous Learning as a Band-Aid for Digital Transformation in FSIs

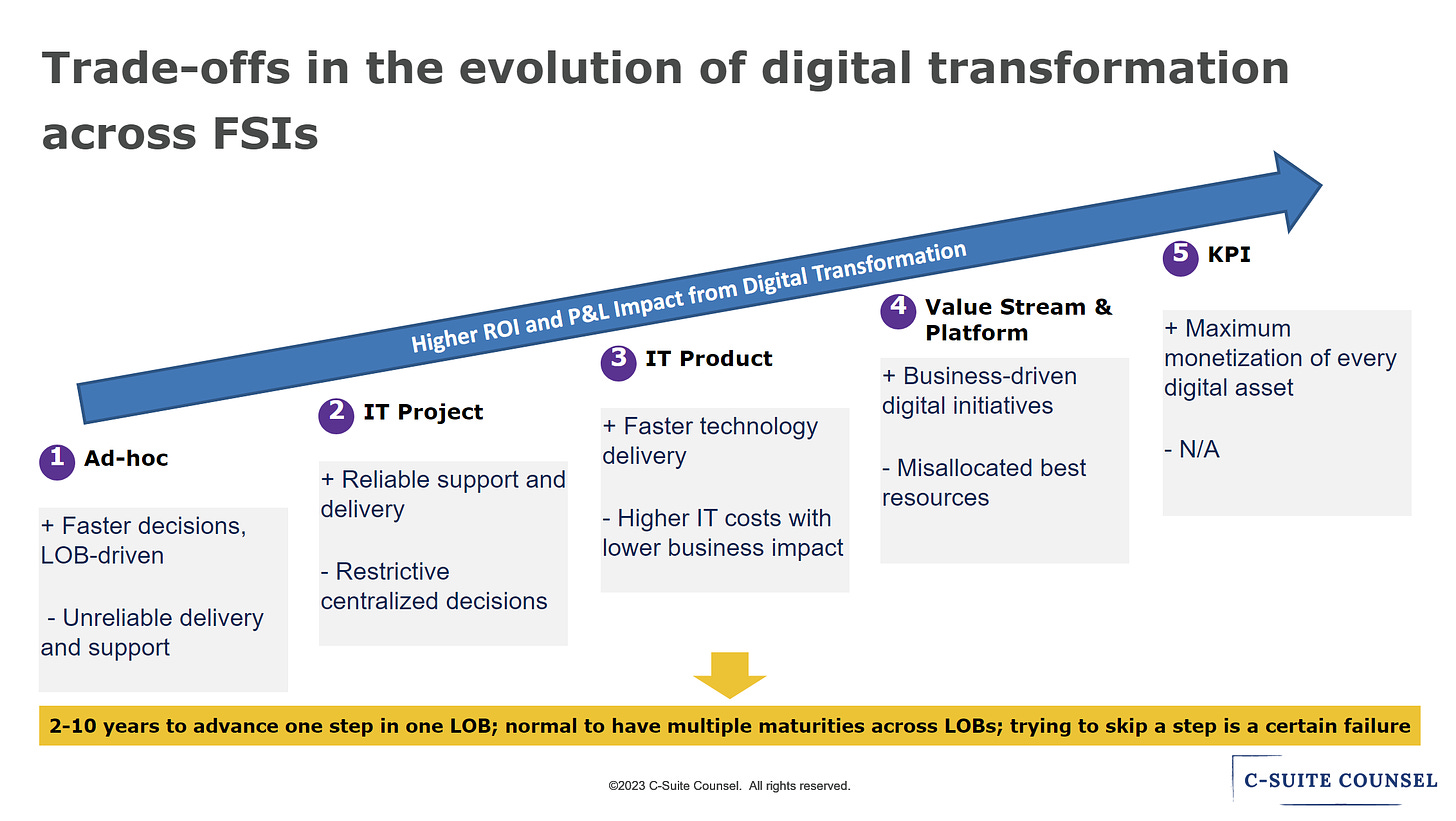

As one of the greatest intellectuals of our times, Thomas Sowell, famously stated, “There are no solutions, only trade-offs.” This is applicable to all big problems, in politics, the economy, and in the digital transformation of FSIs. The analogy in digital lingo is that there is no perfect UX; every re-design will be welcomed by some users and hated by others.

Many FSIs fail to grasp that digital transformation involves the challenging process of reshaping business and operating models. Instead, they often label any substantial digital endeavor as "transformative" without delving into its trade-offs. This is akin to proponents of solar and wind energy who overlook downsides such as increased manufacturing pollution and harm to flora and fauna in the vicinity. However, the consequences of not honing in on specific digital transformation trade-offs are substantial, all the way till reaching the target state.

1. The straightforward learning process in digital transformation

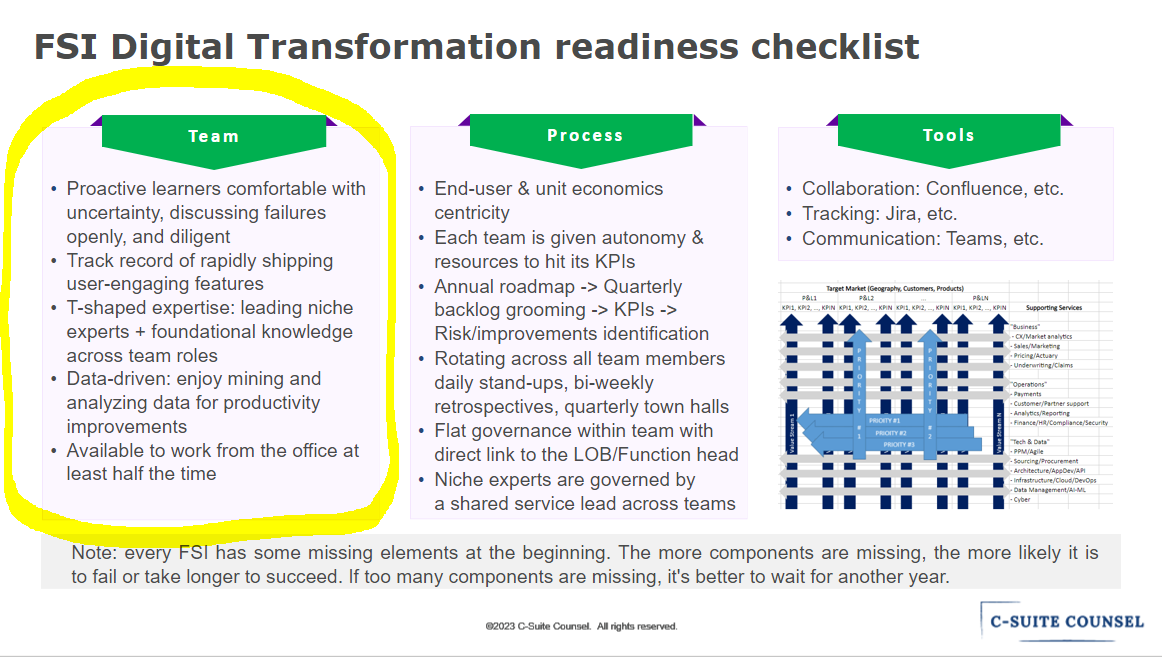

When done correctly, digital transformation is precisely optimized to increase an FSI's profitability. Initially, the focus is on prioritizing the groups that will make more money, followed by identifying the groups that will provide support. This approach involves one group type learning how to maximize profits, while another type learns how to provide the necessary digital capabilities to support them.

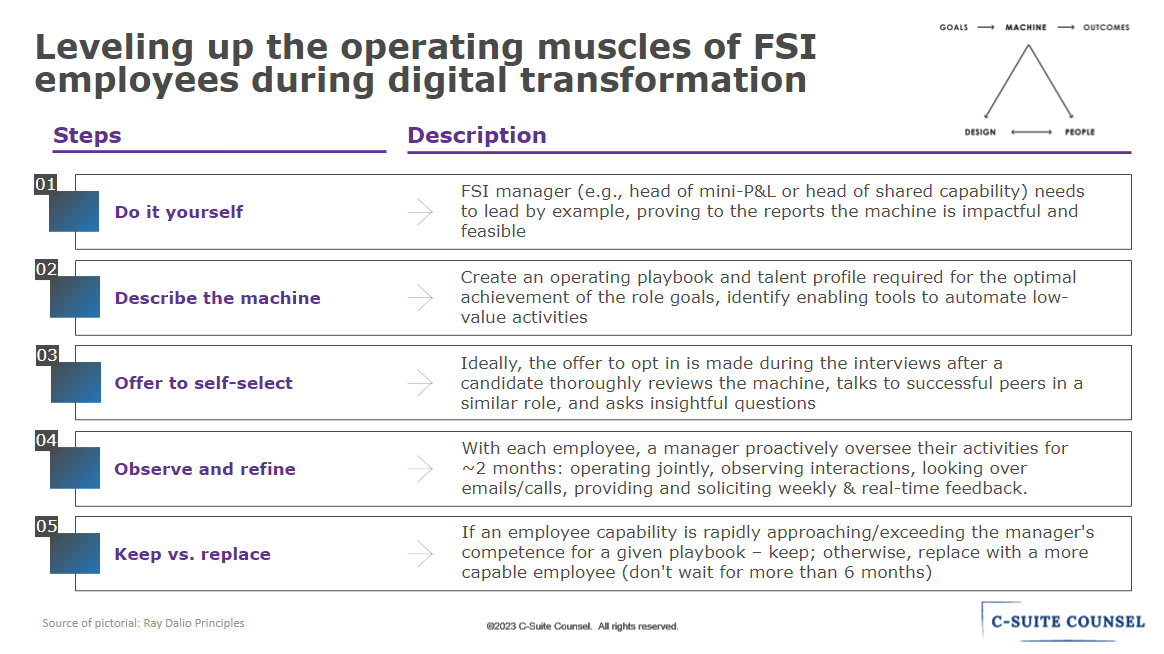

Ideally, some people in both money-making and supporting groups already know what good looks like and could teach others. If not, they engage an internal trainer or a contractor with that experience who could lead everyone by example while leveling up everyone’s operating muscles. The leveling up must start with an executive (manager) of those groups who can then teach their reports once the trainer/contractor leaves.

The enterprise-level employee learning team (sometimes called Learning & Development) is there to accelerate the above efforts with two main outcomes using the least amount of resources:

Scalability of end-users: increasing individual and organizational productivity; and

Scalability of the training group: automating training services.

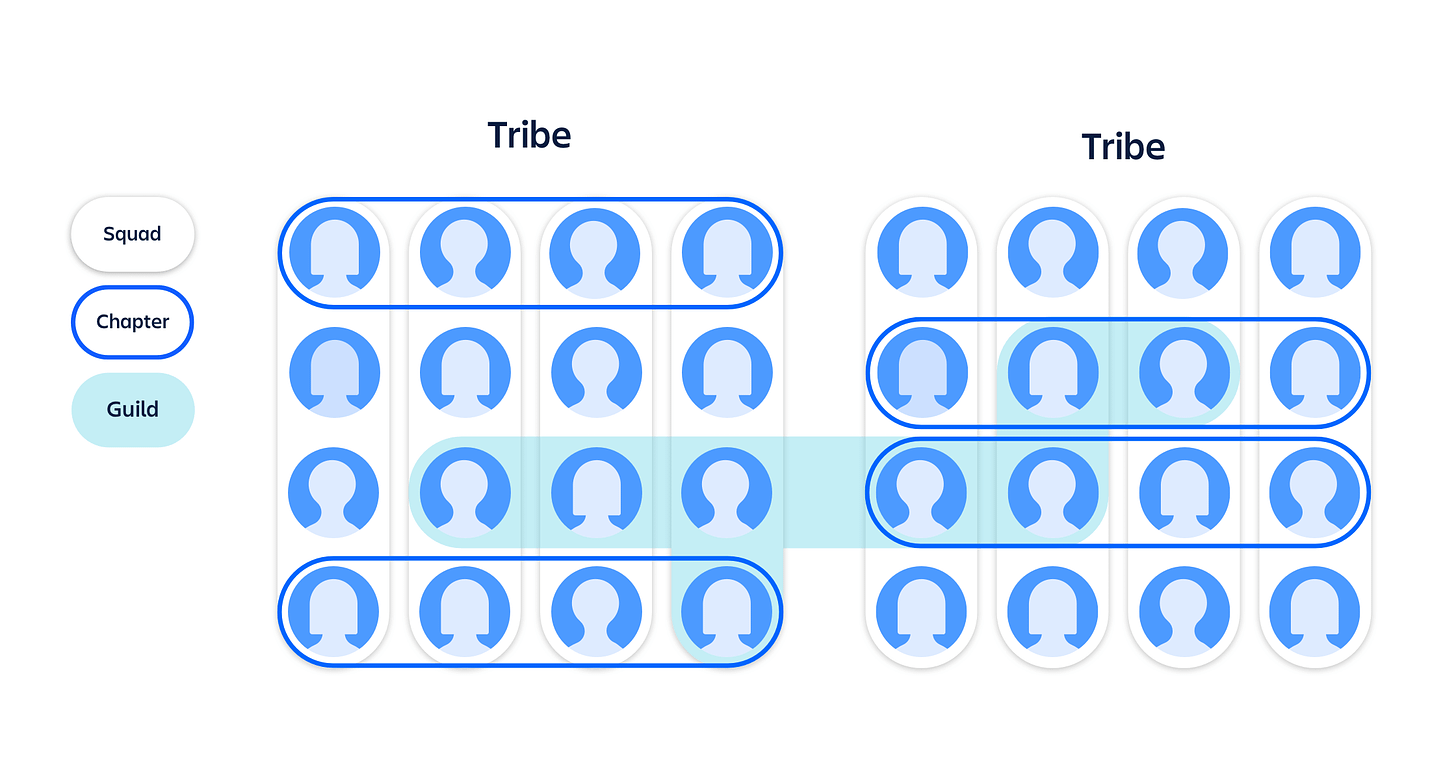

The rest is up to employees if they want to learn something or anything in their spare time. Using Spotify lingo, while Tribes are busy making money and Chapters are busy scaling their support for Tribes, employees are welcome to form Guilds on any topic in case they are getting bored professionally.

2. Simple approach to learning is in conflict with the enterprise-level bloat

As discussed in another newsletter, reducing enterprise bloat goes hand-in-hand with digital transformation, and this process involves eliminating many centralized training programs. However, enterprise management rarely concedes without resistance and often prevails. Cynically, relinquishing control to front-line groups implies giving up power, but enterprise leaders are not deliberately resistant to change just to preserve their positions. Instead, they often lack a clear understanding of the target state practices and are incentivized to promote their services without adequately considering trade-offs.

A recent article by Dilip Venkatachari, the Global Chief Information and Technology Officer at U.S. Bank (the 5th largest bank in the US), illustrates this conundrum:

This is how Dilip describes the North Star metrics for the U.S. Bank learning program:

“Our embedded learning environment takes aim at employee retention and development, helping workers invest in themselves while creating a stronger technology-to-business connection.”

Notice what is missing are the actual North Star metrics for IT executives: making technology support for the business more scalable while enhancing business satisfaction with said support. The right metrics help clarify the scope of learning. The U.S. Bank’s metrics are so vague that they could apply to any centralized learning program. In a large bank like this, there could be hundreds of architects. In digital transformation, that role is becoming obsolete, with some of those employees/managers transitioning into individual contributors within business lines and others being terminated. What is the value in the learning program that retains the Architecture staff and improves their connection to the business?

Like many of his peers in other FSIs, Dilip faces the challenge of navigating true digital transformation, which necessitates collaboration with business counterparts to level up everyone's operational muscles. Hence, it is not surprising that the U.S. Bank CIO tends to view transformation as primarily a technology-focused endeavor.

“The largest technology investment for U.S. Bank came in 2022 when we announced Microsoft Azure as our primary cloud service provider. This move accelerated our ongoing technology transformation… The technology transformation at U.S. Bank is also focused on adopting a more holistic approach to both external and internal talent pipelines.”

U.S. Bank's Enterprise IT is pouring substantial investments into novel technologies and then undergoing significant shifts in enterprise-wide talent sourcing to accommodate these changes. This approach stands in stark contrast to the correct LOB-driven approach to digital transformation, where business units should be the ones determining their technology needs and the associated talent and learning requirements. This situation might be more understandable if it were a struggling small bank seeking to stabilize its operations through centralized processes. However, the fact that the country's fifth-largest bank continues to operate in this manner highlights the immense challenges of achieving genuine digital transformation.

3. Self-propagation of enterprise learning

When an FSI views continuous learning as a vital objective of enterprise-led groups, the expansion of bureaucracy becomes self-propagating. This is why the U.S. Bank places such emphasis on "continuous" learning – there is no inherent mechanism to conclude or at least scale down the program once it achieves the most immediate business goals. The U.S. Bank's continuous learning initiative encompasses four avenues for propagation:

Establishing a flexible learning environment;

Plan: Growing skillsets and knowledge;

Tools: Learning paths and programs; and

Application: Putting experiential learning into practice.

Consider the budget and annual FTEs needed to support all of this: advocating for time allocation for learning, encouraging managers to discuss learning plans, persuading employees to embrace additional learning tools, and facilitating everyone's skill practice in a secure environment:

“… we offer programs such as certification festivals, hackathons, code-a-thons, bootcamps, and other communities of practice for our teammates to hone their newly acquired skills in psychologically and technologically safe, yet productive settings.”

Let’s compare it to how the world’s fastest-growing fintech, Ramp, addresses top-down learning requirements for its new hires:

4. Defining successful outcomes for enterprise-led learning

In digital transformation, the emphasis on scalability implies that support groups like IT should begin each day by asking themselves, "What more can I do to render myself and my team obsolete?" This principle applies even more to enterprise-level groups like Training, which aren't directly overseen by a particular business line. Instead, the enterprise team often gauges their success based on the utilization of their services:

“Since we’ve started this continuous learning journey with our teams, we’re seeing higher employee engagement, an increase in our team’s reported skills and certifications, and a stronger technology-to-business connection across U.S. Bank.”

Such feel-good outcomes would raise a red flag in a top fintech. If the training couldn't be directly linked to enhancing the scalability of an employee and their group, it would likely impede the company's evolution velocity. This is why, when corporate or consultant types enter leading fintechs in the learning function, it often leads to amusing situations.

One such case gained notoriety in 2020 due to the assertive leadership style of one of the world's leading fintechs, Revolut. Instead of being concerned about public perception, Revolut promptly dismissed several recently hired executives in "People Operations" upon recognizing a significant gap in expectations.

The newly hired executives were flabbergasted that they couldn't secure funding to carry out their planned projects. They naturally expected big teams and a large budget, as is the norm in FSIs like U.S. Bank. They couldn't possibly comprehend that learning in a fintech-grade company means a narrow focus on addressing the most significant scaling impediments and that these can often be tackled by a hands-on leader in a Learning group on their own, without the need to hire a team. Nuanced gaps in a high-performance FSI require a very seasoned professional to personally address them.

In summary, in a high-performance company, enterprise-led training is a necessary measure because employees may have been mistakenly hired or moved into roles where they are not leading experts. Learning programs in these firms are not designed to gain a technological edge; they are intended to address upstream oversight issues. Otherwise, they function as a band-aid to conceal gaps in digital transformation.

Should FSIs Buy or Build to Accelerate Digital Transformation?

In an ideal scenario, digital transformation in the financial services industry is initiated by a business executive who recognizes its necessity to significantly increase the company's profitability. This executive assesses the potential benefits of a transformed business in comparison to the initial and ongoing costs and risks. Unless the return on investment (ROI) is evidently substantial, the digital transformation is postponed, and the evaluation process begins anew in the following year.

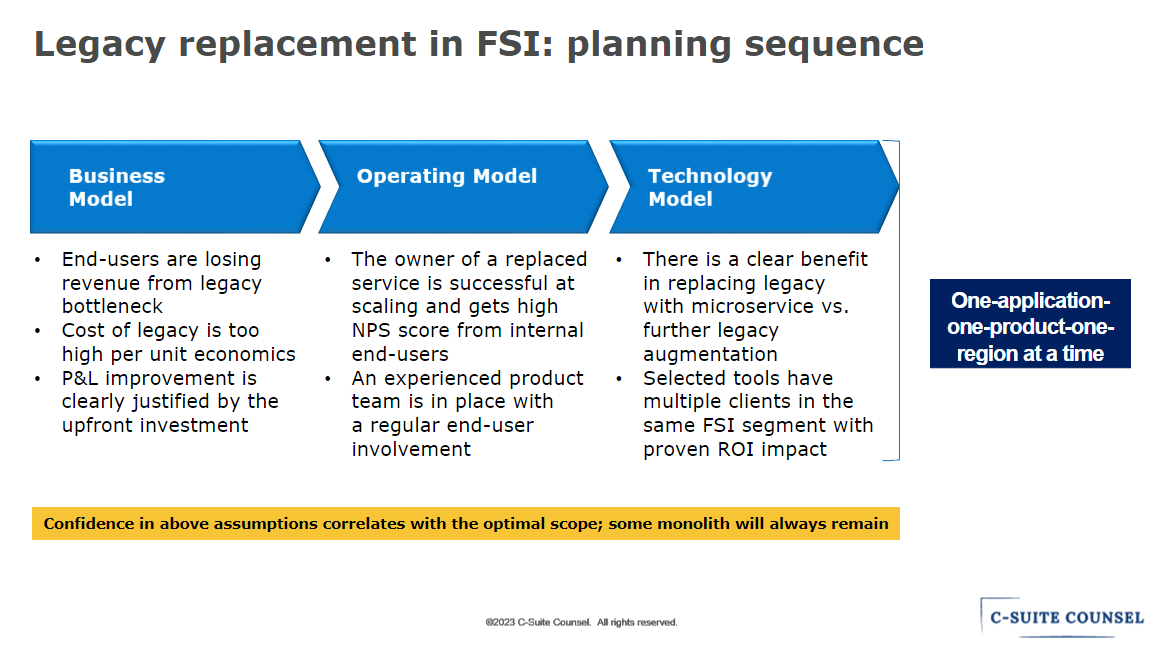

A significant portion of the costs and risks associated with digital transformation in the financial services industry pertains to the replacement of legacy systems. A proactive business executive often finds that replacing these systems with microservices may be more expensive and involve more internal hand-offs, especially when the expected business benefits are not significantly greater. In such cases, they may opt against the transformation project. However, when the benefits clearly outweigh the costs, the crucial decision lies in choosing the type of replacement: whether to build it in-house or acquire it from a vendor.

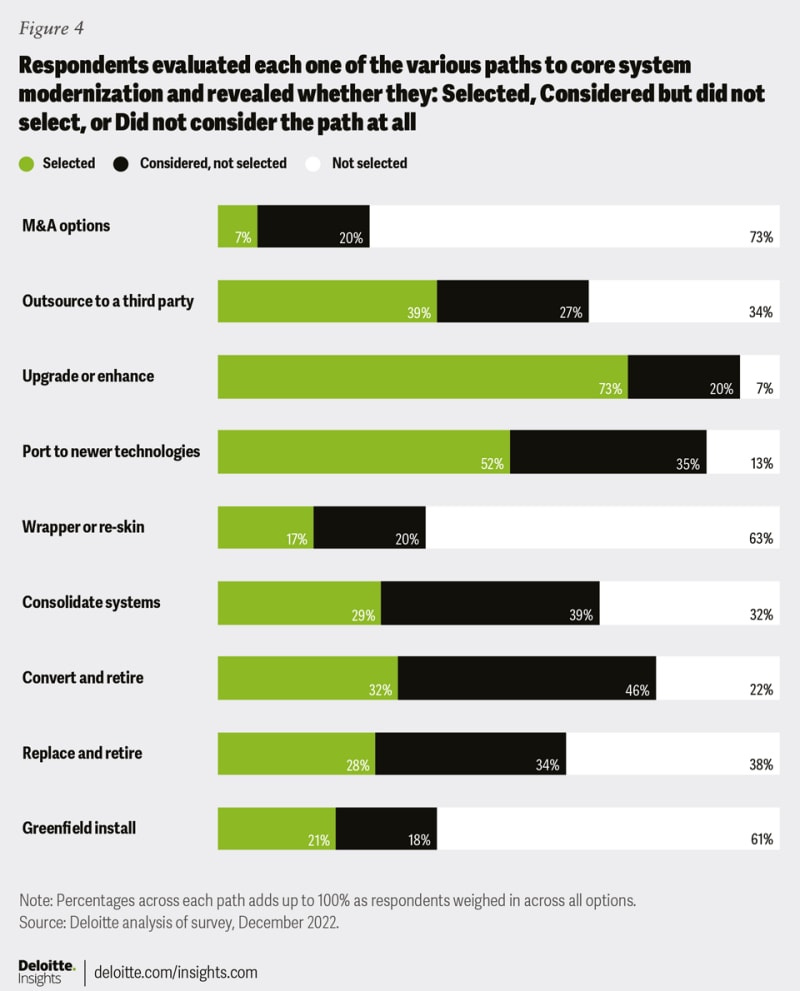

In many financial services institutions (FSIs), the reality doesn't align with this ideal scenario. Typically, it's the IT leadership that spearheads legacy replacement, often termed "platform modernization," with Business providing high-level oversight. These initiatives are funded based on top-down budget allocations, a trend that has seen rapid growth over the last decade, resulting in widespread legacy replacement efforts. Even in the Life Insurance industry, which tends to be less digitally intensive than other sectors within FSI, there has been a significant increase in the percentage of carriers intending to upgrade or enhance their existing core systems, doubling from 36% in 2017 to 73% in 2022:

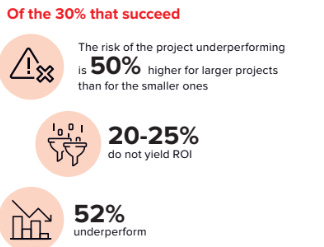

This virtually unconstrained spending on a highly risky endeavor has unsurprisingly led to a high degree of failure. The EY-Parthenon 2022 U.S. Banking Strategic Partnership survey revealed that approximately 40% of all bank partnerships fail to operationalize. The 2023 Innovation in Retail Banking report also found that nearly half of banks express dissatisfaction with partnering with both traditional and fintech vendors.

When FSIs attempt to develop their digital engagement platforms in-house, the failure rate might be even higher. In a recent survey of banks in APAC regions, 70% of these projects have failed due to costly and lengthy in-house efforts. However, even among the remaining 30%, success is not guaranteed:

The decision to buy versus build has been a longstanding challenge for FSIs, and it's only becoming more complex with various intermediate options and different pricing models. Should they choose fintech or traditional vendors? Low code or regular code? Cloud or on-premises? IT leaders now finally have substantial budgets to modernize their legacy systems, but they are not meant to succeed due to a lack of Business engagement in making those complex decisions.

Nevertheless, if the Board, CEO, and investors all believe that doubling technology spending will somehow create business value, IT leadership is smart to play along. CIO pushing against it or insisting on a closer Business engagement could jeopardize their job security. Moreover, many CIOs are enthusiastic about implementing modern technologies. As one CIO of a large FSI once told me, "What kind of CIO would I be if I'm not embracing AI, Cloud, Blockchain, and all the other cool stuff?"

For this typical CIO, there is a simpler criterion to decide between the buy and build decision in order to accelerate digital transformation. Since real digital transformation requires leveling up employees, the CIO needs to pick an option where a more advanced third party, SI or platform vendor, would commit to replacing the legacy system together with FSI staff and managing them in the process.

This way, even though the effort may not meet financial expectations, FSI IT employees would become more effective through intensive on-the-job coaching. Then, when their company finally approaches modernization in a sensible way, the employees will have the necessary skills to maximize ROI.