"Potemkin Villages" in the Digital Transformation of FSIs

Also in this issue: Hey, FSIs, Leave Them Customers Alone

"Potemkin Villages" in the Digital Transformation of FSIs

As with most quaint historical anecdotes, "Potemkin villages" are a myth—a story from 18th-century Russia about creating a nicer appearance to hide the rotten back office, so to speak. Fixing the insides to achieve better outcomes is very hard while repainting the facade is quick - as long as no one tries to take a closer look.

Some FSIs apply this technique to digital transformation, which is supposed to mean the acceleration of business performance by advancing the operating model and leveraging technology capabilities. Instead, they label transformation as large expenditures or large efforts more generally, such as:

Acquiring or setting up startups.

Cutting products, employees, and management layers.

Changing employees' titles to digital-sounding nomenclature a-la Spotify.

Overinvesting in fancy technologies like AI and Cloud.

Those efforts might fool some investors and analysts who don't look too closely, but eventually, most of them become jaded. In a sign of healthier times, "digital transformation" is becoming ridiculed as part of modern corporate speak, increasingly associated with a struggling company.

When an executive extols that their FSI is transforming, in the majority of cases, it means they are repainting the company facade. It's like the periodic clean-up of San Francisco during major gatherings like Dreamforce or APEC. Hassling the homeless to a different area and scaring off criminals with more police presence is welcomed by locals, but they also know by now that there will be no structural changes to make it last.

Digital Facades Don't Work But Are Too Irresistible

The most fascinating example of creating a digital facade is when FSIs set up subsidiaries under a different brand name. While changing the whole company's brand to alter the image might be logical in some exceptional cases, starting a new company and not leveraging the FSI's well-known name always seems counterproductive.

It also sends an implicit signal that an FSI is not trying to transform its core business, operating, and technology models but is setting up a side hassle hoping such a venture could profitably target a new segment, usually, younger demographics. This strategy never works, and yet FSIs keep trying it.

The latest example is MassMutual taking almost a decade to shut down Haven Life due to a 'lack of adoption.'

“As part of our continuous effort to most efficiently and effectively meet the needs of our customers, over time we will shift direct access to MassMutual life insurance products from Haven Life to our own website, MassMutual.com.”

Gaining Efficiency Is Not Transformative

As discussed in another newsletter, cutting bloated bureaucracy in a typical FSI is a prerequisite for digital transformation, especially in reducing the overhead layers of the enterprise groups. But "transformation" literally implies the advancement of the FSI operating model and leveling up of the operating muscles of executives and employees in the transformed groups. That happens very rarely after cost-cutting, especially after the FSI reaches the Level 3 stage, IT-Product digital maturity.

However, differently from other "Potemkin village" techniques, cost-cutting initiatives are easily understood by investors, regardless of how the FSI CEO spins it. The implicit expectation is that a typical FSI has a lot of managers and employees who don't add value, and thus, firing them would save the company a lot of bottom line without impacting the top line. At the extreme, Elon Musk demonstrated that even cutting 80% of staff at X (Twitter) resulted in a higher product launch velocity afterward.

For a typical FSI, that portion rarely exceeds 20%, usually between 5-10%, as seen in the ongoing effort at Citi, the project "Bora Bora." Citi plans to cut at least 10% of jobs in major businesses, following CEO Jane Fraser's strategy to streamline operations with the assistance of Boston Consulting Group.

Labeling a 10% staff reduction with the evocative name "Bora Bora" is clever; it strengthens Citi's upper-level brand image and dispels any hint of toxic masculinity linked to traditional banking. For terminated employees, after years at Citi, this move might be seen as a luxurious retreat, or at the very least, they could get a t-shirt.

The erroneous conflation of efficiency and digital transformation becomes especially evident when the executive in charge of said "transformation" also heads the technology department. An example is Ameritas, a $3 billion revenue life insurer in the US, where Richard Wiedenbeck serves as both Chief Officer of Technology and Transformation. As often discussed, wearing dual hats is a proven approach to transformation compared to having a dedicated head. In a recent interview, Richard demonstrated the correct mindset for managing his dual responsibility:

“I don’t think of it as an extension of the CIO job, but rather as a separate role to ensure we achieve transformation. The good news is I can talk to myself to reset objectives.”

However, the focus of transformation seems misplaced at Ameritas:

The company is in the midst of an enterprise overhaul to drive operational efficiency, not just from a technology perspective, but across business processes and organizational structure.

Transformation is usually too risky and expensive to attempt for anything that doesn't enable significant business growth. Instead of asking the CIO to oversee cost reductions across the enterprise, the optimal path to achieving efficiency is to stop transforming and task the COO with lowering expenses. Bring in management consultants to help if the COO is afraid to push through unpopular changes.

Technology Focus ≠ Transformation

Even when an FSI pursues transformation to achieve top-line growth, having a C-Suite executive in charge who is also responsible for a shared Enterprise group creates a tough dilemma. By the core design of digital transformation, every support role needs to strive to make itself redundant by focusing on higher scalability and user satisfaction with it. The Enterprise IT role is even more challenging since it needs to transition capabilities to the business group to enable maximum autonomy in decision-making. This is doubly unnatural as Enterprise IT doesn't want to relinquish power while some business groups don't want to be responsible for IT. The Enterprise IT CIO's role is to manage that never-ending ordeal.

Most Enterprise CIOs in FSIs don't understand that this is their job in digital transformation. Instead, they continue to act as they did in the 20th century, building shared capabilities in hopes that business groups would leverage them. A recent interview with Kathy Kay, CIO of Principal Group, a $15 billion revenue asset manager, illustrates this point. After starting with Principal in 2020, Kathy focused on enabling five business groups with Cloud and AI technologies. As typical for FSI CIOs, her instinct drove her to develop massive enterprise-wide infrastructure, so business groups would use them one day.

… biggest challenge in setting the stage for her digital ambitions — and one that has involved the entire C-suite — has been unifying the IT operations of Principal Financial’s individual businesses units in order to develop an enterprise-wide data foundation and cloud architecture on which to build its next-generation services... To tackle the unification strategy, Kay and her C-suite colleagues established Enterprise Business Solutions, an internal technology division focused on modernization.

This approach could make sense in less mature FSIs where IT projects are badly managed and business lines don't have competent IT. For more advanced FSIs, this IT strategy typically results in overbuilding once it goes outside of the pilot. The usual rebuttal is that there are shared business opportunities that have to be pursued on the enterprise level. Kathy offers such an example in her interview:

“The customer had a 401(k) with us, for example, insurance benefits, and also asset management services, and [each] of those units did not know they shared a customer. Customers expect to be treated holistically.”

In such examples, I ask CIOs which business executive is responsible for implementing the business case by higher cross-selling and retention of those supposedly dissatisfied customers. There is almost never an answer, and that is the danger of technology-centric transformations. Without evolving the operating model with more ownership for digital solutions placed with business executives, additional technology focus could become just a prettier facade.

To be fair to traditional FSIs, the operating model for enterprise-wide use cases is hard to master, even for the best fintechs. Alex Johnson highlighted such infighting at Block between its core business lines, Square and Cash App:

In addition to squabbling over data, the teams took months to decide on a revenue-sharing agreement for the fees the Cash App transactions would generate from Square merchants. Eventually the quarreling teams agreed on an even split.

Back to traditional FSIs… many transformational technology-centric efforts of synchronizing legacy systems on some modern AI-Cloud-native platform are hugely disruptive to business groups with no performance improvement. Bain recently analyzed 42 of the world's largest banks, and its data confirms an intuitive point: technology focus does not guarantee high performance for most FSIs.

Spending a lot on technology and having more in-house engineers doesn't guarantee superior performance, even for the most tech-savvy FSIs like Capital One, whose outcomes are similar to many other large banks with a relatively small focus on technology.

Such a counterintuitive finding is similar to spending more on public schools and hiring more teachers. Washington DC is one of the biggest spending school districts in the US while having below the nation’s average student proficiency rates.

Similar to U.S. public schools, FSIs should resist the urge to throw money at "Potemkin villages" of digital programs across the board—it is better to fix only a few areas instead.

Hey, FSIs, Leave Them Customers Alone…

… All in all, it's just another product on the wall.

Even Pink Floyd in 1979 couldn't have predicted that the English overbearing educational practices of the 1950s, described in the song, would ever resemble the financial services and insurance industries. Until recently, consumer pain points were widespread. Traditional FSIs were linked to high prices for inadequate services and lacked automated products to address core needs, rather than micromanaging their customers.

Today, customers are inundated with indistinguishable offers and marginal features that will have no visible impact on the quality of their financial lives. I encountered this personally when building SaveOnSend for cross-border money transfers. After meeting hundreds of low-income migrants in their communities, I was surprised to discover that they were not “suffering” from Western Union and MoneyGram’s tight hold on the market. Persuading them to try a fintech offering was quite a challenge.

Traditional FSIs Have Become Pretty Good

One of the main reasons why there are fewer major pain points is that FSIs have become more effective. Just consider credit card companies in the US. Working at American Express from 2005 to 2007, we completely missed the ball on the higher risks of delinquencies. It was puzzling to see late payments from small businesses and consumers in good standing, but there was no capability to figure out that it was due to them prioritizing mortgage payments.

The losses in the aftermath were so staggering that credit card companies' stocks collapsed by 80% or more, and, since the 2005 highs, stocks like Capital One have only gained 30% in total:

But FSIs that survived got to work, improving their operating models, data analytics, and technology to avoid making the same mistake. As a result, the credit card delinquency level in this cycle has not moved much in the last year, despite the Fed Funds rate being as high as in 2006-2007:

Some improvements are becoming so refined that they are resulting in regulatory fines. Citi just paid $26 million for discriminating against Armenians concentrated in one town near Los Angeles. Citi noticed an organized fraud pattern and started profiling similar applicants, asking for more documentation, and denying their credit applications when not feeling comfortable.

Higher fraud rates among certain ethnicities in specific zip codes for particular financial services and insurance products have been well-documented. FSIs now have digital capabilities to identify and preempt such fraud, but they are not allowed under a bizarre suggestion that a bank is doing this out of discrimination against a particular group. The same banker types who are taking risks by adding phantom accounts for anyone are somehow also capable of refusing someone legitimate business out of ethnic dislike. Sigh…

Traditional FSIs are Running Out of Material Use Cases

Not only are FSIs getting better at managing their core products, but the challenge of introducing a new digital product to significantly boost the slope of their revenue growth trajectory is also becoming increasingly difficult. Consider the world’s largest hedge fund, Bridgewater Associates, where I worked a decade ago. The performance of its flagship fund, Pure Alpha I, became legendary in the earlier years, but for the last decade, while passing the $100 billion AUM mark, it has been a dud.

After layoffs earlier in 2023, Bridgewater’s main priority became piloting a fund run by machine learning techniques. The general idea of robo-management seems proven by fintechs like Betterment, founded in 2008, which has reached $40+ billion in AUM. However, Bridgewater already has its own automatically rebalanced fund, called All Weather, also with $40+ billion in AUM. Offering clients another option, even if it is called “machine learning,” is less likely to add a significant uptick in growth compared to even a decade ago.

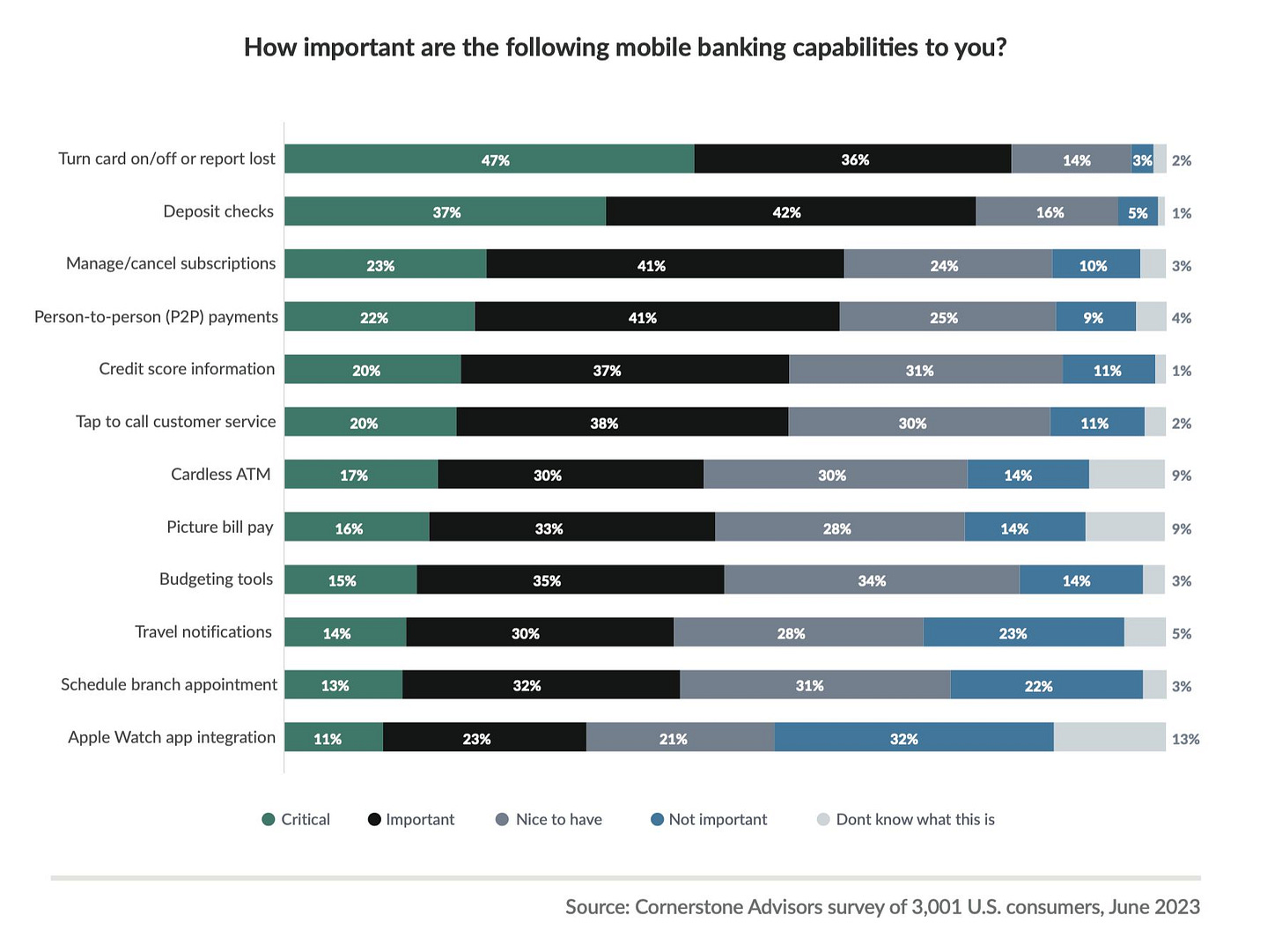

The recent Cornerstone Advisors bank and consumer survey illustrated a broader point of increasingly minor pain points by ranking which digital capabilities matter within the mobile app. Most of the critical features are already available from banks, and the missing ones tend to be less important:

As a more specific example, Regions Bank just announced a new solution - a combination of various tools to help lower-income consumers with weak credit improve their credit history. The anchor product would be a credit card requiring a $250 minimum deposit.

Most promises by FSIs and fintechs to improve the credit of low-income consumers have not been proven with data. This is not surprising, as it would require a fundamental change in a person’s behavior, akin to embracing a long-term diet or cessation of vaping. Is it worth targeting consumers with another product before a larger FSI or fintech has proven that it works at scale?

Fintechs Are Becoming R&D Labs for FSIs

Unlike FSIs, startups are directly incentivized to launch those marginally useful products, although they wouldn't call them as such. VCs have billions that they want to invest in fintechs, so a startup founder just needs to show a humongous TAM and invent a flywheel of low CAC, which is now even easier with hallucinating Chat GPT tools.

That is why we are seeing increasingly narrow use cases. For example, in the past, everyone was worried about young professionals not saving enough for retirement; now, a MAJOR pain point is supposedly that they are saving too much:

While two decades ago, the hope was for startups to disrupt FSI incumbents with 10X better products, a decade ago, the expectation started to downgrade to a 10% improvement and shot at being a contender. These days, fintech differentiation is often minor enough that it is unlikely to attract millions of consumers without expensive marketing incentives. For example, Charlie, a relatively new fintech, was founded to address "the financial woes of retirement," but its key feature is to get social security payments up to 5 days early.

Traditional FSIs should view such efforts as their free R&D lab. There will always be fintechs like Ramp, which are approaching a billion in revenue while still growing rapidly. But, in most cases, FSIs could take time and wait to see if some feature seems to be gaining traction, and only then build it to their customers in that particular segment.

Sure, if your FSI has the ambition of being a category leader like Amazon, Netflix, or Spotify, by all means, keep launching beautiful products to wow consumers before they even know that they need it. For everyone else, listen to customers' complaints, and if there's no sizable pain point, perhaps it's time to give them a bit of a break.