What Is Causing Lack of Talent Flow From Fintechs into Traditional FSIs?

Also in this issue: Why Would FSIs Keep Investing in Physical Locations?

What Is Causing Lack of Talent Flow From Fintechs into Traditional FSIs?

A short while after joining Mastercard in 2012, I attended a company event with clients. Not knowing who was who, I approached two people discussing a mobile application. When I asked if they also worked for MasterCard, they looked at me with disgust and said, “Thank God, No,” before walking away. “They work in a digital bank,” my colleague explained, smiling at my confused expression.

I knew beforehand that it was cooler to work for Goldman Sachs than for a universal bank or to be an investment banker rather than a retail banker, but this was something new. What later became known as fintech was a new preferred destination for cool people. This revised hierarchy seemed illogical: not only was fintech a much riskier and more hectic environment, it also paid less than a similar position in a traditional FSI. But the attraction lay in a different dimension: a new generation of top talent prioritized meaning and freedom above money and stability.

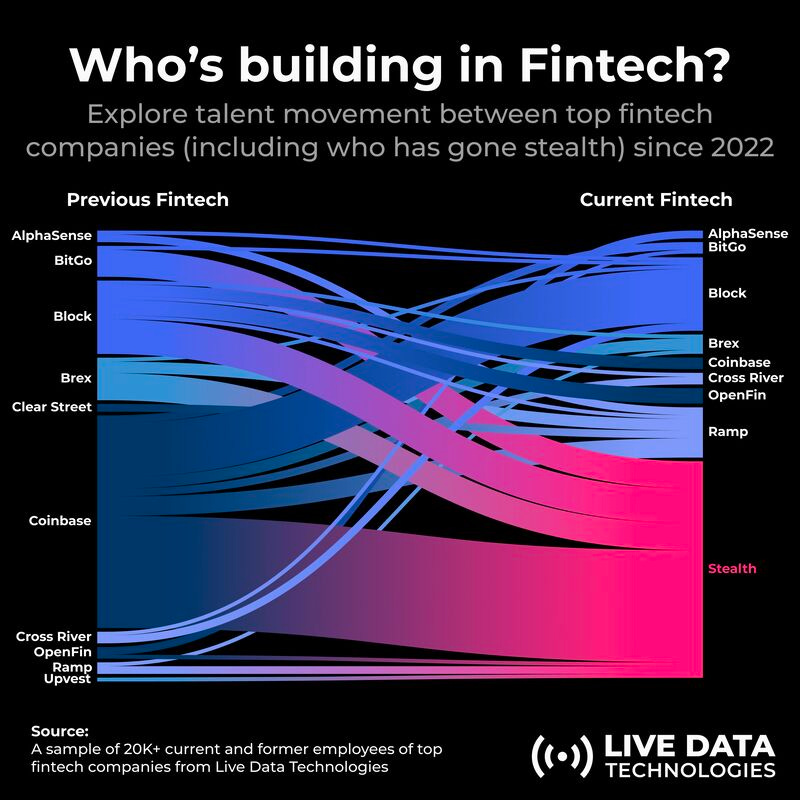

A recent study of over 20,000 employees of top fintech companies illustrated the stark segmentation of talent in financial services between fintechs and traditional FSIs, with virtually no overlap across the two groups. If somebody departs a fintech, they move to another fintech or join a new startup:

The exceptions are rare. A typical case would be a fintech hiring traditional FSI executives into back-office roles in Finance, Legal, or Compliance. The painful lesson for fintechs has been to avoid hiring too many corporate types at once. Revolut learned that lesson in 2020 when it fired several high-ranking managers in their “People Operations” department just a few months into the job. They came from traditional companies and seemed unprepared to operate in a scrappy environment:

This confusion from corporate types highlights a key gap in understanding what it means to transform. For fintech executives, transformation is a daily routine that they need to practice first themselves, and then lead others by example. For traditional FSI executives, digital transformation typically means hiring people with a digital background, purchasing technology, and then offering high-level oversight without undergoing personal transformation. In fintech, personal accountability is usually celebrated, whereas, in a typical FSI, it is often replaced with creating the right perception through upward management.

Without a critical mass of fintech-grade talent, changing the culture of traditional FSIs is almost impossible. At a recent staff meeting, the newly hired head of Citi’s Wealth division, Andy Sieg, made such an attempt in the spirit of ongoing reorganization and the removal of committees and managerial layers. Andy implored staffers to avoid managing up, and every person emailed him afterward that God broke the mold when creating such a brilliant executive:

As FSIs endeavor to digitally transform, they could undoubtedly benefit from fintech-grade talent. It is much more effective to have someone on the team who has internalized what "good" looks like than to hear about it at a conference. FSIs won’t achieve this by merely placing a startup accelerator next to their main building or setting up a separate fintech subsidiary. The hope for such virtual osmosis has been attempted by dozens of large FSIs, each wasting hundreds of millions of dollars in the process.

The minimum success factor is to have a CEO, business product, and shared services heads who are willing to personally level up and gradually push their peers to transform over the years or even decades. With these three executives on board, they could start bringing in fintech-grade employees, one at a time, learning from them, and protecting them from office politics.

Why Would FSIs Keep Investing in Physical Locations?

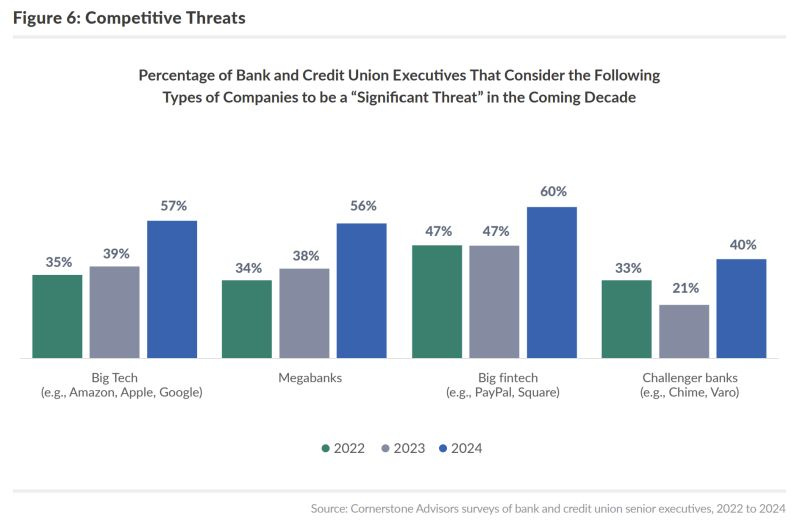

The debate about the necessity of physical locations for FSIs has been ongoing since the late 90s. Initially, it was believed that digital kiosks would replace humans, followed by the idea of websites, then mobile applications, and eventually generative AI. The threat was amplified by the fear of new digital-only players among Big Tech, payments fintechs, and challenger banks. These "disruptors" are thought to excel in digital capabilities to such an extent that their competitive threat is on par with that of top incumbents:

Never mind that the biggest financial services and insurance success stories from Big Tech are wallets, while Goldman Sachs is attempting to exit its partnership with Apple with no apparent takers. Never mind the struggling PayPal or the fact that challenger banks are experiencing rapid deceleration in their growth. Even if the only real threat to FSIs comes from their peers, the debate boils down to a practical question: Should FSIs invest in physical locations beyond bare minimum maintenance?

A large contingent of industry experts responds with a resounding "Hell no," accompanied by typical arguments:

Financial services are as straightforward as e-commerce or gaming.

Young people don’t visit branches.

People only go to branches because their banks are not digital enough.

Branches are only necessary for very poor or wealthy consumers.

Physical Locations are Cool Again

None of those arguments reflect the real data, but when such experts see an FSI making major investments in physical locations, they dismiss such news as a PR stunt, not believing that there might be a solid business case behind it:

However, it’s not just Chase emphasizing branches. Nationwide Building Society in the UK recently advertised keeping branches open as a competitive advantage against rivals like Santander who are reducing their physical footprint. Nationwide is now being sued for that comparison:

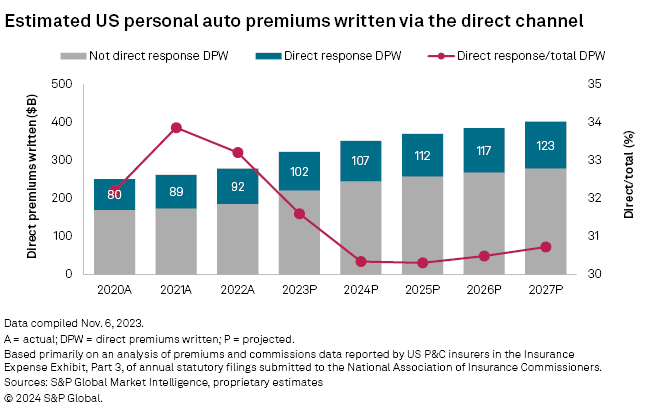

For decades, auto insurance could be purchased directly. And yet, insurance offices remain a fixture of suburban strip malls, while the rate of purchasing auto insurance directly is stuck in the 30-35% range:

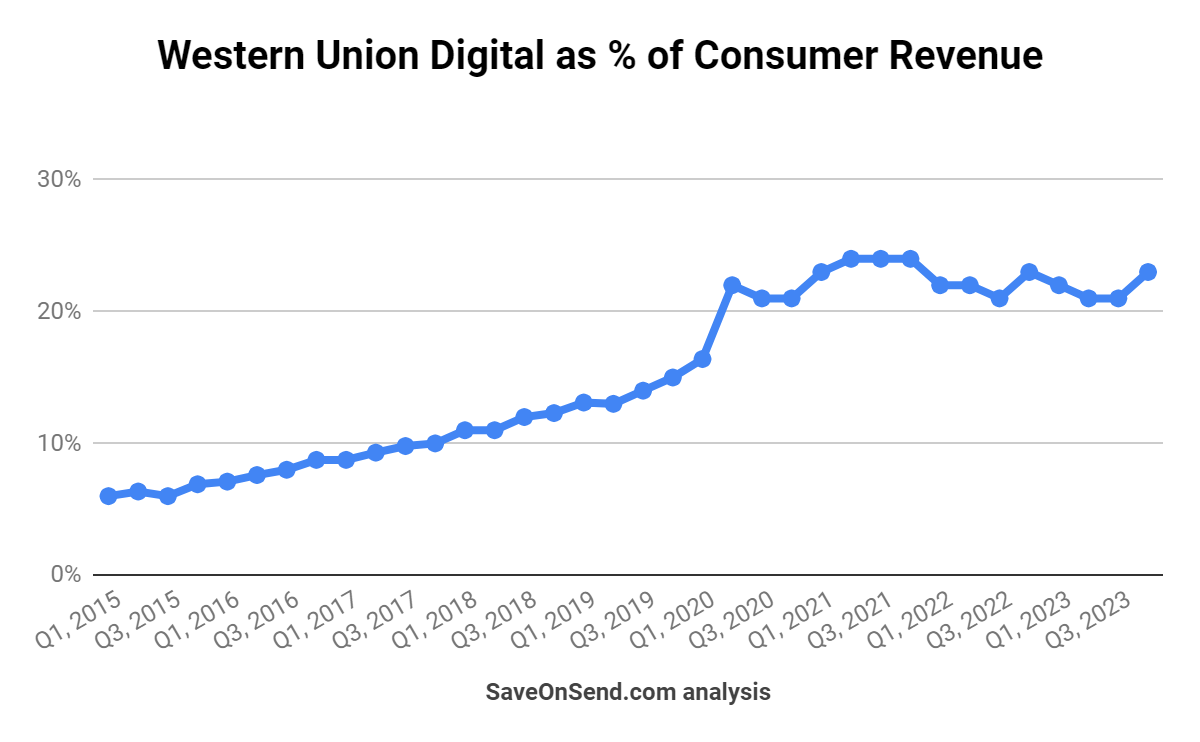

Ok, but at least payment services should not need a physical location. Every cross-border money transfer player probably has the app at its point, so there is no reason for their customers to spend more money and time on in-person transfers. Well, the global incumbent, Western Union, has been stuck with an even smaller ratio of digital transfers, in the 20-25% range:

Moreover, Western Union is innovating heavily with different types of physical formats:

“In 2023, we opened 100 new owned locations in 200 new concept stores which increased our controlled distribution strategy by over 35%. Recall that by enabling an exclusive Western Union experience in high-impact locations, we believe we have more control over the customer experience can test new products and services and creates a new low-cost acquisition engine for our digital business.”

One of its top competitors, Ria Money Transfers, has been on a location growth binge, expanding its global physical footprint by 10% annually with close to 600,000 outposts.

As for the experts' opinions about young people and financial services, do Gen Zers cringe at the thought of visiting a branch? It is quite the opposite. According to the 2023 survey by User Testing, 79% of American digital bank users wished their banks offered some of the perks traditional banks do, with 60% of Gen Zers prioritizing the ability to talk to humans for customer support.

Consensus Bias Meets Reality

In psychology, the false consensus effect, also known as consensus bias, occurs when a person sees their own choices as common and appropriate across a wider population. This is what has been happening with experts since the 90s, who have been steadily bewildered by why FSIs would invest in physical networks. Since these experts and their circle conduct financial services and insurance activities virtually, they mistakenly assume that most consumers are like them.

I had that bias too as someone who handled finances digitally until starting a fintech and realizing how wrong I was. The proponents of the "branch-is-dead" argument are missing some key facts about the majority of FSI consumers. They:

View financial services differently than e-commerce and other mobile apps, with much more risk aversion and confusion.

Are irrational and gullible and could easily make suboptimal financial and insurance decisions without human guidance.

Prefer human interaction with experts versus learning new topics on their own.

Add to that the fact that chatbots have been the biggest source of customer complaints in FSIs and that physical outlets are also used for small business clients whose needs are more complex and not easily digitized or handled by a call center, and it becomes obvious that the offline form will make it into the 22nd century.

Instead of heeding doomsday experts, FSI executives should reflect on the advice of former Chase Co-CEO Jennifer Piepszak, who described a practical mindset required for thinking about physical and digital channels:

“It’s not a binary choice between branch and digital. Most of our banking customers engage with both.” She added that the two channels “cast halo effects on each other, as we see higher digital account production in markets where we have a branch presence.”

Digital transformation's only raison d'être is to accelerate business value creation. Sometimes, FSIs would still find digital initiatives above the ROI threshold, but with the industry becoming increasingly mature, it would be getting much harder with every year. Don't let consensus bias prevent you from considering profitable investment into the good old physical channel.