From the Driver's Seat: Insights of a Former Blackrock Aladdin Technology COO and Delivery Head

The story of BlackRock Aladdin's inception, its business performance, differentiating factors in business, operating, and technology models, and key lessons learned.

From the Driver's Seat: Insights of a Former Blackrock Aladdin Technology COO and Delivery Head

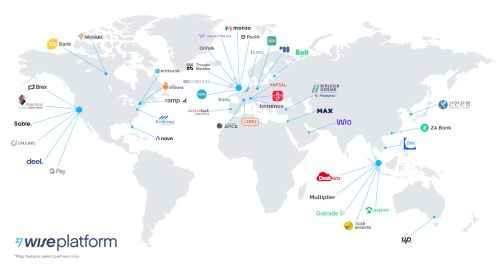

The pinnacle of digital transformation is to scale an exceptionally effective digital business to the extent that your rivals would pay for its underpinning platform. An FSI might dominate its primary sector, and it might even capitalize on data for other sectors, but receiving payment from a competitor is the ultimate flex. This is exceedingly uncommon across all industries, and Amazon's success in having other major e-commerce participants pay for AWS usage stands as one of the few isolated instances. Even one of the world's most effective fintech firms, Wise, is taking a decade to get a sizable revenue from such a platform.

As you're aware from our newsletters, we regard Capital One's credit card division as one of the foremost among traditional FSIs globally in terms of digital capabilities across the five 21st-century pillars: Agile, AI, API, Cloud, and DevOps. Capital One has harbored ambitions of monetizing its platforms for a decade, and it even established a distinct business group named Capital One Software. However, the only solution it has managed to devise is a generic spend management tool for Cloud, and it hasn't generated a noticeable revenue.

Hence, it's even more remarkable that one FSI managed to achieve this feat, and not just in recent years. In 1999, roughly a decade after its spinoff from Blackstone, BlackRock embarked on the monetization of its core platform, Aladdin. This endeavor unfolded somewhat by accident. Another large financial institution became aware of BlackRock’s unique internal platform and essentially asked to purchase it from them. Only after that initial success did the company decide to proactively offer it to others.

Fast forward to today, Aladdin oversees assets worth more than $20 trillion for over 200 clients, contributing around $1.5 billion in revenue from other money management firms to BlackRock’s overall business.

In 2003, four years after Aladdin began its monetization journey, Daniel Rosner became an early hire for its implementation team. Over the next two decades, Daniel held positions such as Head of Aladdin Delivery, COO of Core Transactions Processing, and Head of Core Compliance, among other leadership roles. Daniel recently shared with FSI Digital Transformation Weekly the valuable insights he gained from spearheading such transformative digital efforts.

Similar to our newsletter about fintechs that are already operating at the target state of digital transformation, this discussion might appear overwhelming for many FSI executives. They may not have the opportunity to personally implement this model in their professional lifetime and may rightfully perceive these advanced insights as "rocket science." However, even in the journey to a base camp, it could be beneficial to understand the distance and general direction to the summit. With this knowledge, all of our readers can hopefully gain insights into what the ultimate "good" looks like.

1. Business model

Daniel joined Aladdin with only six live clients, but the list already included one of BlackRock’s top competitors. As we often discuss, the business model determines the success or failure of digital transformation efforts for traditional FSIs and of scaling trajectory for disruptors. Without a unique business model, no amount of agile routines or a cool tool stack could gain a sizable market share by itself. Aladdin recognized the importance of the right "secret sauce" early on.

"In those early years of Aladdin, the competition was homegrown platforms or the 'best-of-breed' combination of vendors. Both solution types included a massive number of interfaces that had to be maintained with a large staff of technologists including often front-office interventions but would frequently break anyway. Aladdin offered a first-of-a-kind integrated platform that enabled clients to focus on core business while obtaining more valuable analytics."

A significant aspect of the integrated system's value proposition was not only that everyone had access to the same real-time data, but also that any corrections or quality improvements made in one part of the organization would have positive implications for all users throughout the organization. In contrast, with a 'best-of-breed' approach, data quality concerns require individual attention for each system - a solution applied by one team might not necessarily yield benefits for other teams using different systems.

Aladdin’s advantage had to be significant enough to not only compel competitors to pay BlackRock but also to entrust it with their most proprietary data. The company discovered how to make data sharing a key component of its value proposition:

"At that juncture, many asset managers were unable to generate daily risk analytics, leading to occasional losses due to late detection of unfavorable positions and incorrect trades. Third-party data platforms lacked access to real-time information, whereas Aladdin integrated risk reporting and trading modules. This integration meant that as trades were entered into the platform the risk system automatically had access to real-time positions, giving clients transparency into broader portfolio risks."

Of course, the major draw for clients was also the industry depth of business processes and data models offered by Aladdin. Clients valued the fact that BlackRock used Aladdin on par with other users, which meant that the platform always had to be top-notch to meet the expectations of a market leader. This user-provider model or "dogfooding" approach led to the development of features that no vendor could possibly match. More than a decade later, Aladdin finally triggered competition among other FSIs like State Street, prompting them to spend billions in attempts to minimize BlackRock's platform dominance.

The distinctive product quickly sparked word-of-mouth recognition within the industry, resulting in the majority of Aladdin's clients coming via referrals. To solidify its initial success, Aladdin offered a simple financial engagement, in stark contrast to the complex and painstaking contract pricing often associated with FSI vendors.

"We were practicing SaaS before even recognizing the term. Our usage fees were uncomplicated, with some variation based on client size. Clients would acquire the complete solution without engaging in convoluted à la carte negotiations. Monthly implementation costs were fixed, with us assuming the associated risks. This value proposition may not have been ideally suited for smaller players, but mid-size and larger players appreciated our straightforward approach."

2. Operating model

The paramount concern when managing financial relationships with competitors revolves around data control. An inadvertent exposure of competitors' positions and trading data to BlackRock's staff could have potentially irreparably damaged the platform's credibility.

"Our platform gains access to the most valuable asset – the portfolio data - of clients, who are also BlackRock's competitors. We went to extraordinary lengths to ensure data segregation and information security, with SOC2 audits providing third party assurances as to effective controls around data leakage risk from Aladdin to BlackRock's core business. Instead of relying on verbal assurances, clients could assess concrete information and provide feedback on the governance and the technological framework between BlackRock and Aladdin."

Likewise, there were intriguing discussions within BlackRock about whether to make Aladdin available to competitors. Aladdin's mission of aiding clients in concentrating on their core business implied that they were becoming more adept at potentially undermining BlackRock's competitive stance. Additionally, accommodating external clients on the same platform meant their demands wielded significant influence on the product roadmap, at times conflicting with BlackRock's preferences.

"In the initial years, BlackRock harbored confidence in its superior intellectual property across the board. Eventually, it came to recognize that client feedback was highly valuable in pinpointing improvements for Aladdin's roadmap. The advantages of utilizing a best-in-class platform continued to expand with the addition of more features and asset classes, as BlackRock alone wouldn't be able to identify and flesh out all these requirements."

In contrast to the typical approach of FSI vendors who often merely pay lip service to client centricity, Aladdin constructed an intricate playbook to discern new prospects for product expansion versus leaving clients constrained by existing options. This endeavor demanded considerably elevated expectations from the Aladdin team, requiring members to acquire the ability to iteratively collaborate with clients on potential alternatives within limitations. As Aladdin's array of offerings continued to grow, the art of balancing competing demands from both a diverse set of clients and a large internal client emerged as a pivotal determinant of success.

Another intricate operational aspect of platform monetization involved the coordination between BlackRock's asset management and Aladdin teams as they collaborated to engage and serve the same clients. The challenge lay in determining where to draw the line between cross-introductions and sharing proprietary information.

"A holistic relationship approach only played a role in a select few large client scenarios, given that the majority of our growth stemmed from referrals. In cases where BlackRock asset management or Aladdin teams working with these major accounts identified a potential expansion opportunity for the other team, they would only facilitate an introduction to the client. The direct sharing of client data within the firm would never happen without the client’s knowledge and approval."

When addressing client delivery and support interactions, many FSI vendors claim a commitment to agility and efficiency. However, the underlying emphasis on short-term profits frequently drives these vendors to prioritize the optimization of resource costs. Consequently, this tendency often leads to the establishment of extensive delivery teams comprised of both onshore and offshore resources, often relying on more tactical and mediocre talent.

In contrast, Aladdin adopted an approach similar to that of many of today's successful fintech companies. They recruited a few exceptional resources, who were then empowered with strategic decision-making authority.

"Having overseen and directed numerous Aladdin implementations, I gained a newfound appreciation for the scarcity of resources we utilized in comparison to the norm among core platform vendors. With just a handful of individuals, we were effectively replacing the 'hearts and lungs' of clients' operations with Aladdin. In stark contrast to clients' harrowing tales of projects gone awry with other vendors, our implementations were consistently executed on time."

One of the primary reasons why most vendor implementations tend to greatly exceed the planned timeline and budget is attributed to their sales-driven culture. In scenarios where new information emerges, implementation teams lack comparable authority and are often not empowered to realign with clients for necessary pivots or to maintain a firm stance. Moreover, once the implementation concludes, an entirely different group of individuals usually takes charge of day-to-day support. Aladdin's operational model was unique in this regard.

"Our Implementation group assumed singular ownership from the initial planning stage through go-live, but we invested in smooth transitions and hand-offs at the beginning and end of each project. For example, typically the implementation team was involved before a final contract was signed, and the ongoing support team would join in the late stages of the implementation. Such close collaboration ensured that after go-live, clients continually benefited from the latest product features as their requirements evolved. During renewals, this effectively deterred our clients from seeking alternative solutions to address new needs."

Aladdin's organizational structure wasn't significantly different. It comprised standard units such as Business Development, Implementation, Relationship Management, and others. This is why the common strategy employed by FSI C-Suites to initiate reorganizations instead of pursuing true transformation often fails to yield substantial value. What holds more importance is the quality of talent brought into these groups, the level of individual accountability they carry, and the extent of autonomy granted to each front-line team.

"Right from my initial implementations, I always felt remarkably empowered to make critical decisions with clients, including the ability to say 'no.' I was confident that Aladdin's leadership would have my back."

Passing through revenue milestones of $10 million, $100 million, and $1 billion naturally led to increased specialization and scalable processes. When clients began systematically raising concerns about specific aspects of the value proposition or when Aladdin could not deploy critical features quickly, this often signaled the need to establish dedicated teams. For example, by shielding developers from ad-hoc requests and establishing a single product pipeline, it became easier to prioritize the most important features.

Adding new organizational units is where Aladdin’s approach of cultivating excellent yet lean talent proved especially valuable. Accompanied by strong employees devoid of excessive bureaucracy, more direct engagement across teams becomes feasible, as long as everyone retains clearly defined primary responsibilities.

3. Technology Model

Aladdin’s decision to adopt a SaaS model more than two decades ago was revolutionary. It occurred well before the trend became widespread and even before Amazon set the standard. This decision had obvious consequences for its technological distinctiveness (click for more on its tech model).

This situation is reminiscent of the almost mythical "API Mandate" issued by Jeff Bezos for Amazon in 2002, famously concluding with the line "Anyone who doesn't do this will be fired. Thank you; have a nice day!" Within Aladdin's technology model, several deficiencies existed, but one aspect was more crucial than all the tool choices combined.

"The decision to adopt a SaaS model was influenced by a practical consideration: to simplify technology maintenance for clients. This level of control over the software allowed us to continuously enhance the product, whereas traditional vendors might only offer one or two major releases per year. Moreover, vendor upgrades on the client side often transformed into substantial projects, introducing significant changes to a client's customizations and potentially necessitating new contracts. Competing vendors also had to contend with the challenge of supporting multiple software versions due to differing clients' decisions about upgrades."

Also similar to Amazon's early years, making an internal platform available to external clients compelled Aladdin to adhere to significantly higher development standards. Each crucial functionality had to be configurable to accommodate various client preferences, and the underlying code had to be elegantly designed to handle this at a massive scale.

The brilliance of these early design elements might seem commonplace in today's context. However, during that era, it was challenging to identify an FSI vendor that adhered to these three fundamental rules of scalable platform architecture.

There should be one way to access a piece of data, or for example, book a trade. Don’t reinvent the wheel.

Front-end applications do not have access to databases or filesystems. They must utilize backend services to accomplish their needs.

Services can run on any host, be moved whenever needed, and can be scaled up by simply starting additional instances (on any host). The corollary is that applications using the services should never need to know the host a service is running on, or be responsible for things like load-balancing.

In summary, the integration of several superior differentiators across its business, operational, and technological models in contrast to client in-house solutions and vendor offerings explains Aladdin's unparalleled success. It wasn't a matter of luck or miracle; instead, it resulted from a series of clever decisions combined with leadership intensity to see them through.

In conclusion

I trust that this firsthand account will serve as inspiration for more FSI executives within the most advanced financial services and insurance firms to consider piloting their platforms for a competitor. You can directly connect with Daniel on his LinkedIn page for further insights. To delve deeper into enhancing your platform management strategies, I recommend exploring this newsletter.