Combatting Rot in Your FSI by Returning to Basics

Also in this issue: How Can Digital Transformation Help FSIs Do Good?

Combatting Rot in Your FSI by Returning to Basics

"Stop bringing up USAA as a case study; it is the only example we ever hear, and we can’t replicate their military affinity anyway!" demanded an FSI executive of a top-10 US insurance company in 2015. He asked me to name an FSI that was a gold standard in digital customer experience, and I couldn’t think of anyone else in USAA’s league.

Since then, USAA has had its first-ever loss, paid a huge fine for not fixing rudimentary AML deficiencies, and its customer scores cratered to the lowest levels among traditional FSIs. What happened?

In my trips to USAA’s HQ in San Antonio, I have witnessed the rot firsthand. From opaque decision-making to hardened organizational silos to a chaperone waiting for me outside of the restroom, USAA increasingly felt more like the Pentagon than a Seal Team 6. The original pioneering spirit and vision seemed gone, and the cultural carriers among the leadership were supplanted by executives from less nimble FSIs. The decision-making focus seemed to have shifted toward more short-term financial results and politics, which crushed not just customer but also employee reviews:

To be fair to USAA, such rot is a natural phenomenon in both traditional FSIs and most fintechs. I call it the Second Law of Digital Transformation in FSIs: Entropy of the Operating Model Increases Over Time. Yes, one can hide its impact through short-term tricks, aka growth hacking, but it mostly works well for a novel product like PayPal in the early days. With so many choices today, clients are more sensitive to being misled, and without an effective and transparent operating model, it is hard to win in a crowded competitive field.

Take, for example, one of the best-known neobanks for small businesses in the US, Mercury. It promises transparency in pricing and features quite attractive specific attributes of its value proposition. However, once you dig a little deeper, their savings account offers only 0.001% interest, and their Treasury account requires a $0.5 million minimum and a specific corporate structure.

Of course, Mercury knows that if it displayed those points, fewer people would sign up for the account. So, employees are learning how to mislead customers for short-term gain. Thus, the seeds of long-term rot are taking hold.

Are Big Tech/Digital Natives Still Superior to FSIs?

Fine, but at least we could always look to Big Tech, leading Digital Natives, for inspiration on what the effective operating model is like. Well, let’s check on how Google is doing.

In its quest for winning in Payments, Google first launched Google Wallet in 2011, then replaced it with Android Pay, then conducted a Google Pay Send revamp, then launched Google Plex, and now it is shutting down Google/Android Pay in the U.S. to focus its payment resources on Google Wallet. Google seems to have expanded Silicon Valley's motto “Fail Fast, Fail Often” to “… Repeat Mistakes.”

Lack of vision and opaque execution have permeated even the most sacred part of Google’s formerly winner-takes-all culture, its R&D. I asked Google's generative AI bot Gemini a factual question about whether any fintech has a higher market cap than Chase. In one sentence, it managed to make 3 out of 3 factual mistakes. Not only was it off in its comparison data, but it also got the simple math wrong in confusing which number was bigger:

While ChatGPT also exhibits clear biases and occasionally makes factual errors, Gemini’s mistakes were so atrocious that Google's CEO had to shut down the creation of human images and acknowledge the unacceptable extent of failure:

Google found itself becoming Exhibit A of Conway’s law: “Organizations that design systems are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.” The more decay in the operating model, the more confusing products a company would create.

Google aside, we often discuss how just three companies are responsible for all operating model practices that FSI executives need to know: how Amazon was operating two decades ago, Netflix 15 years ago, and Spotify a decade ago. There has been nothing better developed on a model level, with all improvement being around underlying implementation tactics.

However, similar to Google’s today vs. two decades ago, this does not mean that FSI executives should target how these three companies operate today. Here is how Netflix’s Head of Data & Insights and Engineering recently explained why she keeps her data teams centralized rather than embedding them within businesses:

Better career path across data teams

More cross-pollination of ideas

More truth-telling to the rest of Netflix

Do you notice something major missing in this rationale?

Those three reasons would be expected from any Enterprise C-Suite executive (CFO, CIO, CMO, CTO, CISO, etc.) in an average FSI: “I don’t want to share my resources, and other groups should come to me for the opinion on how they could do better.” It is a great gig if you could get it. That list is glaringly missing two North Stars for any support function: making P&L groups increasingly satisfied with provided enablement and achieving it with more scale.

The FSI C-Suite Creates Rot and Only They Can Fix It

An ancient proverb “a fish rots from the head down” could be translated into corporate lingo as “organizational rot in FSIs is caused by C-Suite executives.” In a struggling FSI like USAA, the C-Suite needs to reflect on how to get the operating model back to the basics that made it great years ago. If they weren’t around during that more effective period, do they understand what made Amazon, Netflix, and Spotify so effective in the first place (not necessarily how they operate today), and can each executive move their groups to that target operating model?

Whoever is the weakest link in that regard needs to be quickly leveled up or replaced with an executive from more effective FSIs or even other industries. A recent CEO survey illustrated such an issue with Chief Marketing Officers. Too many of them are perceived to be pursuing a siloed agenda rather than enabling the achievement of company-wide goals:

Citi’s CEO Jane Fraser began addressing the rot in recent months. After failing in her first couple of years as CEO to fix the opaque operating model with empathy, she began removing sources of expanding entropy by cutting management layers and bringing heads of divisions from more effective peers like Bank of America for Wealth or J.P. Morgan for Banking. But for the decay to start reversing, those executives now need to be empowered to bring a critical mass of like-minded hires with them, and the CEO would have to be involved in culture clashes on the side of legionaries.

Then again, how to address rot if its main source is the CEO? The board members would be wise to remember Shakespeare’s Hamlet. When Marcellus, an officer of the palace guard, proclaims, “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark,” he then follows Hamlet and his father’s ghost to learn the details despite Horatio’s resistance. In the end, the ruler does get replaced with a foreigner, but if it is the CEO who is causing the rot, what other choice does FSI have?

How Can Digital Transformation Help FSIs Do Good?

I worked at Bridgewater Associates before learning about Elon Musk’s explanation of The First Principles Method, but in retrospect, my work felt like that method was scaled to every excruciating detail, from the color of a new carpet on a trading floor to the first sentence one says in a meeting with their reports. Hence, my shock when years later, post George Floyd, I heard how Ray Dalio, Bridgewater’s founder, answered the interviewer's question on his $50 million donation to a prominent medical school to solve health inequity. “How are you sure that they can solve that problem?” “They know what they are doing,” Ray responded.

No, they don’t; nobody knows. You could force someone to stop smoking and drinking while only eating healthy food and regularly exercising, but there is no need for $50 million to know that would lead to better health. What is unclear is how to modify peoples’ behaviors outside of applying straight-up dictatorial measures to the already largely unhealthy population. What are the cost-effective incentives, not mythological “nudging”, that can create a lasting change?

If a government is too incompetent to solve this while nonprofit medical institutions are disincentivized to have a healthy population, maybe we could learn from private businesses about what it takes to create sustainable positive change in their customers' lives. And we don’t mean “sustainable” as a marketing trick of NetZero or Sustainable commitments which means doing the same activities by either buying fake forest or issuing cards with a different type of plastic:

BMO offers a more interesting case of attempting to drive positive change in Collections. In a recent interview with the Banking Transformed podcast, Anuj Vohra, Head of North American Collections at BMO Financial Group, shared details of their financial wellness program. Implemented in partnership with fintech Springfour, the program refers customers in collections to local services that provide advice on job search, financial management, or grocery savings:

The premise is simple: while BMO is chasing delinquent customers, Springfour’s network of services could potentially improve their financial well-being and make them more likely to repay their debt. So, what has been the cumulative impact over the five years since the partnership launched? 800,000 referrals and millions more dollars in repayments. For a top-10 USA bank with 13 million customers, this doesn’t seem transformative on an annual basis or in terms of the value recouped per referral. But it is a great start. Where should BMO go from here?

The starting point is always a directly aligned North Star. If the goal is to improve customer financial wellness, the North Star should be measuring BMO's success in creating that specific impact. By randomly splitting customers in collections to be pushed into Springfour referrals, how significant is the resulting improvement in less total debt, more emergency cash, and higher credit scores? By measuring the direct impact, BMO will discover that some participants get worse despite referrals or because they received bad advice. If the overall results are not impressive, it will challenge BMO to reevaluate this program.

Through this more intensive approach, BMO will also discover how to use data to fix upstream root causes in consumer targeting and underwriting models. These root causes are broadly divided into two categories: (a) selling the wrong product, and (b) selling to the wrong customer.

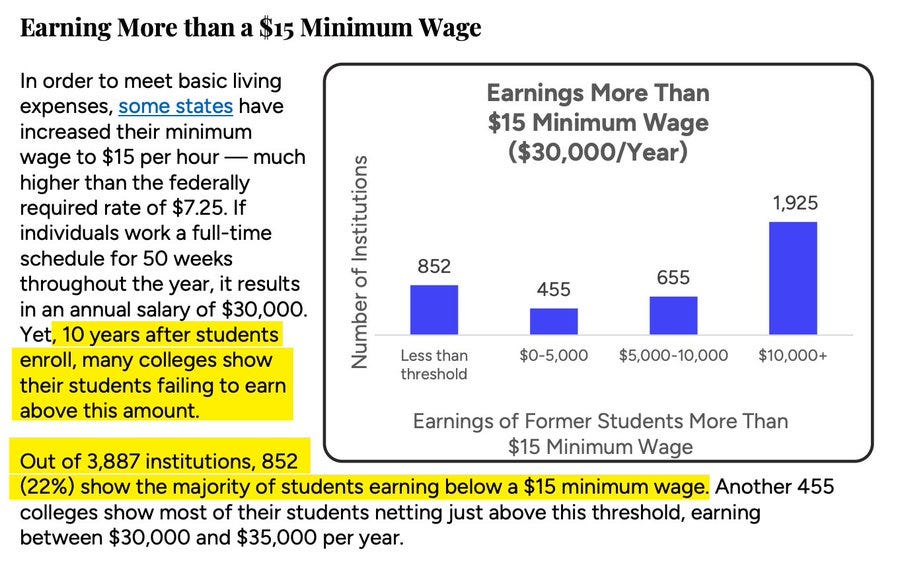

For example, currently, the supply of adults with college degrees in the US is twice as high as the market demand for them. As a result, half of college graduates earn less or around minimum wage 10 years after enrolling in college. Doing good in this case is not giving those types of high school graduates a better student loan, but not giving them one at all.

Finally, it’s important to remember the Law of the Instrument when it comes to digital transformation - sometimes the best way to help customers has nothing to do with digital capabilities. For example, home insurance became very expensive in Florida not just because of the weather, where analytics could play an important role in setting up the right prices and recommending the best way for consumers to build and fortify their homes. Excessive legal costs also were a major contributing factor. Despite having 8% of the country's weather-related insurance claims, Florida faced 75% of lawsuits. Once insurance carriers helped the state to identify and close regulatory loopholes that enabled rampant lawsuits, they started coming back, giving struggling consumers more choices.