The Service Desk in FSIs: A "Canary" in the Digital Transformation "Coal Mine"

Also in this issue: How Come Fintech Executives Forge Their Own Destiny While FSI Executives Fall Victim to Circumstances?

The Service Desk in FSIs: A “Canary” in the Digital Transformation “Coal Mine”

In a traditional FSI, no head of a service desk or customer experience group could answer these basic questions with facts:

Which repeat complaints have the biggest impact on Net Promoter Score (NPS)?

How is my group’s scalability trending year-over-year?

Which product/engineering initiatives should be stopped?

This is due to two fundamental differences in the operating model between traditional FSIs and top fintechs:

Decision-making: top-down within siloes vs. empowered and cross-functional; and

North Star: efficiency (budget, complaints) vs. effectiveness (scale, NPS).

As a result, many executives in traditional FSIs are really good at optimizing within their siloes. They have dashboards to track every process's operational performance, and they regularly implement automation tools. Such service desk and customer experience groups are optimized and adaptable to whatever solutions and end-user segments their FSI wants to pursue. But they are not even considering how to make themselves redundant.

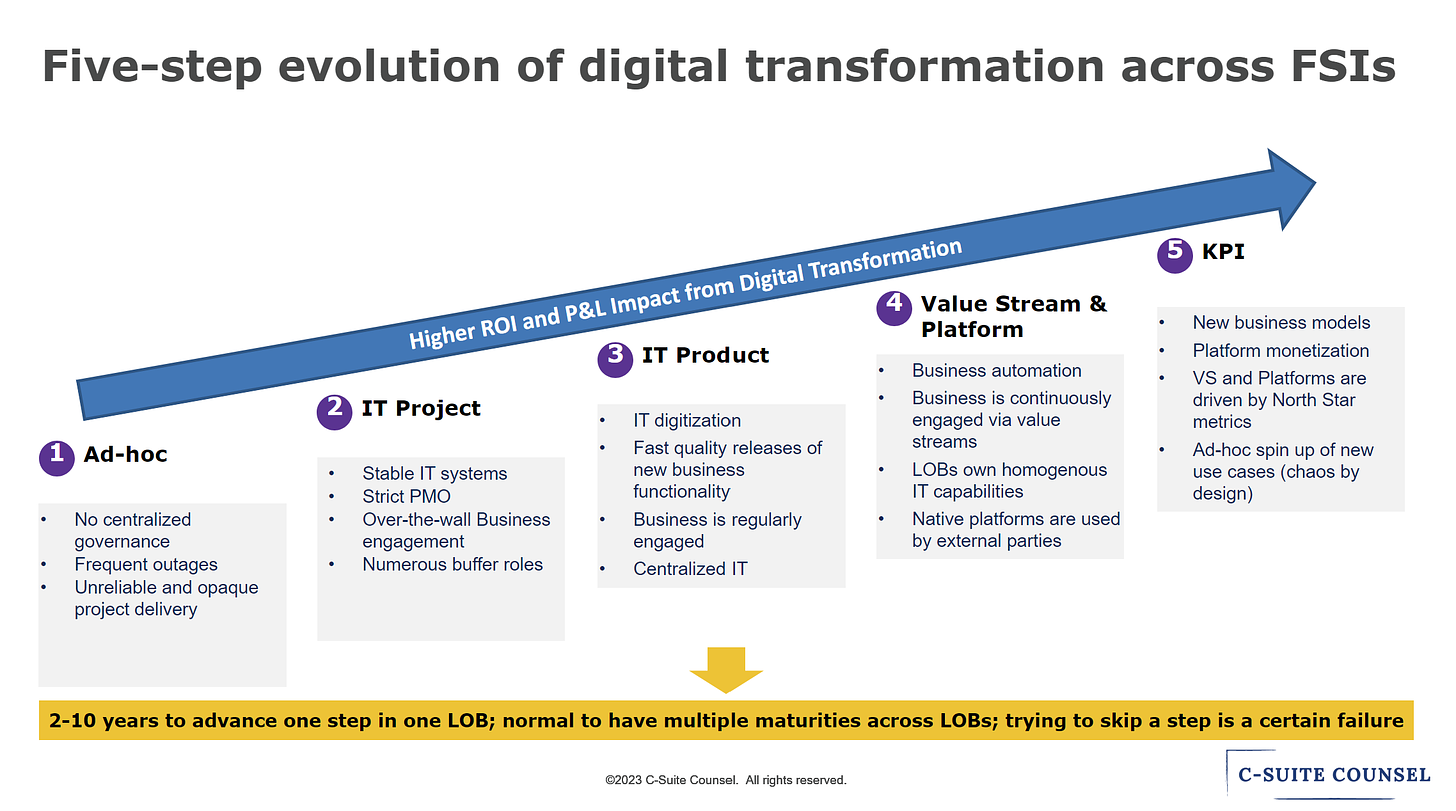

1. Why is digital transformation required?

"We keep track of top client queries and regularly pass that information to Sales and Product groups," responds the Head of Customer Experience of a mid-size asset management firm. When we look at the list together, all the reasons are high-level: status of funds, status of payments, incorrect balance, etc. It is hard to discern what is really driving those issues and what solutions would make the most difference. As is typical for FSIs, there are often some high-level queries that drive the majority of customer or employee complaints.

“Eighty percent of queries across Citigroup’s 96-country network — which includes more than 200 million clients — are payment status queries.”

In this context, help desk and customer experience groups are great indicators of the pace of digital transformation since they have the data to drive change but often don't use it effectively. While other groups in an FSI might have anecdotal evidence of where customers and employees seek fundamental change, these groups are primary aggregators of such data. How they use that data could quickly tell if an FSI is iterating through one-off projects, rapidly becoming more efficient, or is starting to focus on adding value and scalability.

When I meet with VPs and more senior heads of those groups in traditional FSIs, they typically view their roles in a silo. Some have attempted to engage continuously with upstream groups, but usually without a reciprocal interest. As a result, they pass along data with the most common queries and then wait to be engaged. Even more infrequently, anyone asks for their opinion about making fundamental changes in a customer product strategy or a technology solution.

To change such a dynamic, FSIs have to transform their operating model from the top, where a more senior executive would start coaching a cross-functional team on how to collaborate on gradually eliminating the underlying root causes of customer queries.

2. Question everything

With coaching from a more senior executive, a cross-functional team could feel comfortable starting to question everything. Initially, it starts with how the business and IT work together on addressing customer queries, but eventually, they could level up to look at how to preempt customer and employee queries when launching new solutions. Here is another question that no head of a service desk or customer experience group in a traditional FSI could answer:

"What gaps in the internal processes caused a high degree of end-user queries after the most recent product launch?"

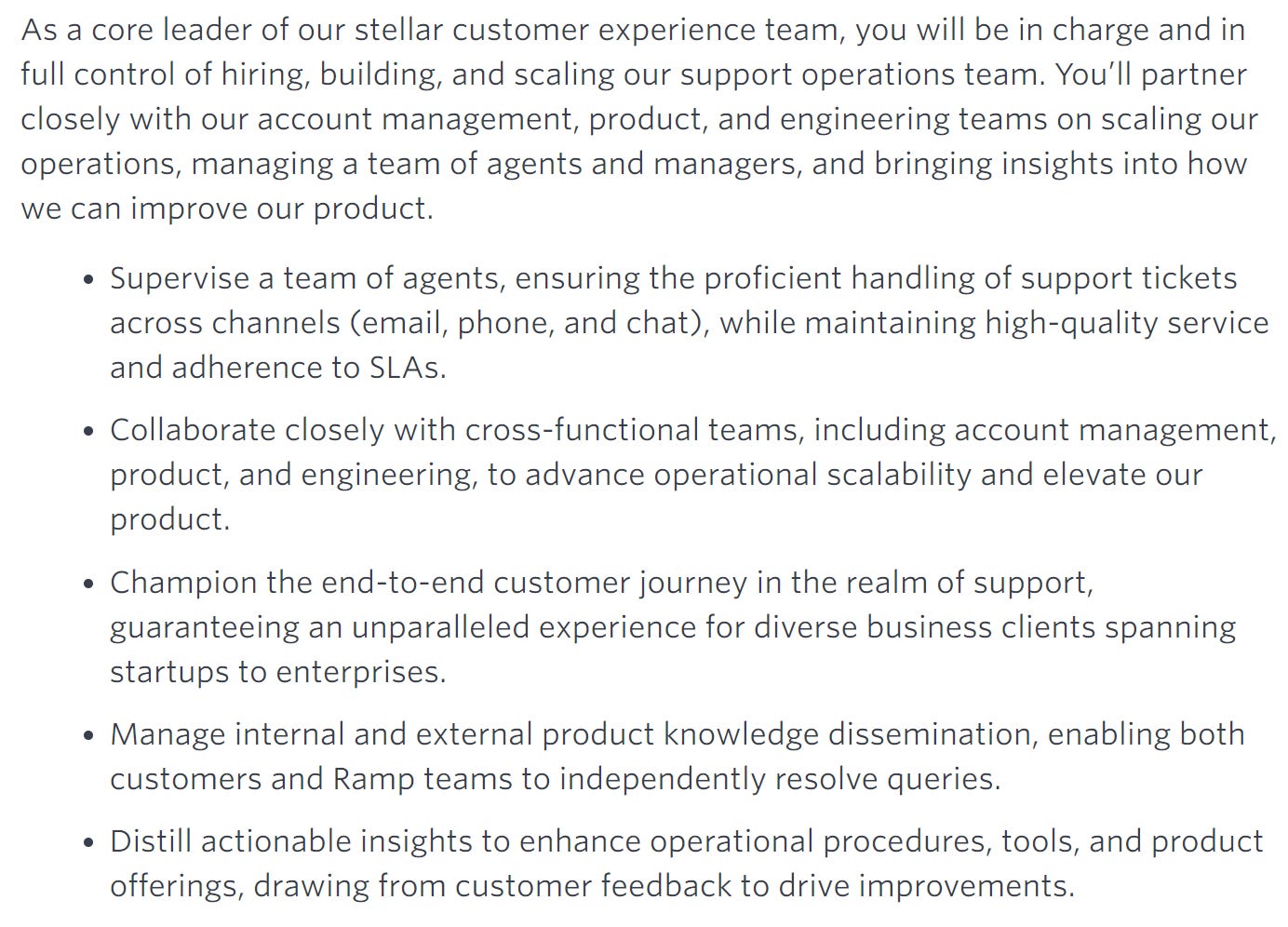

This question goes against their optimization mindset. They are not hired to think through company-wide playbooks like in a fintech. Here is how Ramp, the fastest-growing fintech to reach $100M in revenue, describes the role of a Customer Experience Manager:

3. The KPI-centric target state

Once the reactive clean-up of queries is completed, followed by proactive changes in playbooks for launching new products and technologies, the final step is to embed support costs into the P&L of granular value streams. In a digital transformation, every customer query is treated as a symptom of an upstream mistake in the FSI operating model. The best way to eliminate repeat mistakes is to assign negative incentives to the specific teams that created them.

This might feel like rocket science to a typical FSI executive, but imagine the current alternative - the company is selling multiple products to multiple client segments without really knowing their costs in each because it is unable to break down substantial support efforts for those customers and employees. It means some types of products could be losing money, and some could be too costly, and the leaders of those business areas lack such pertinent information to decide their growth strategy.

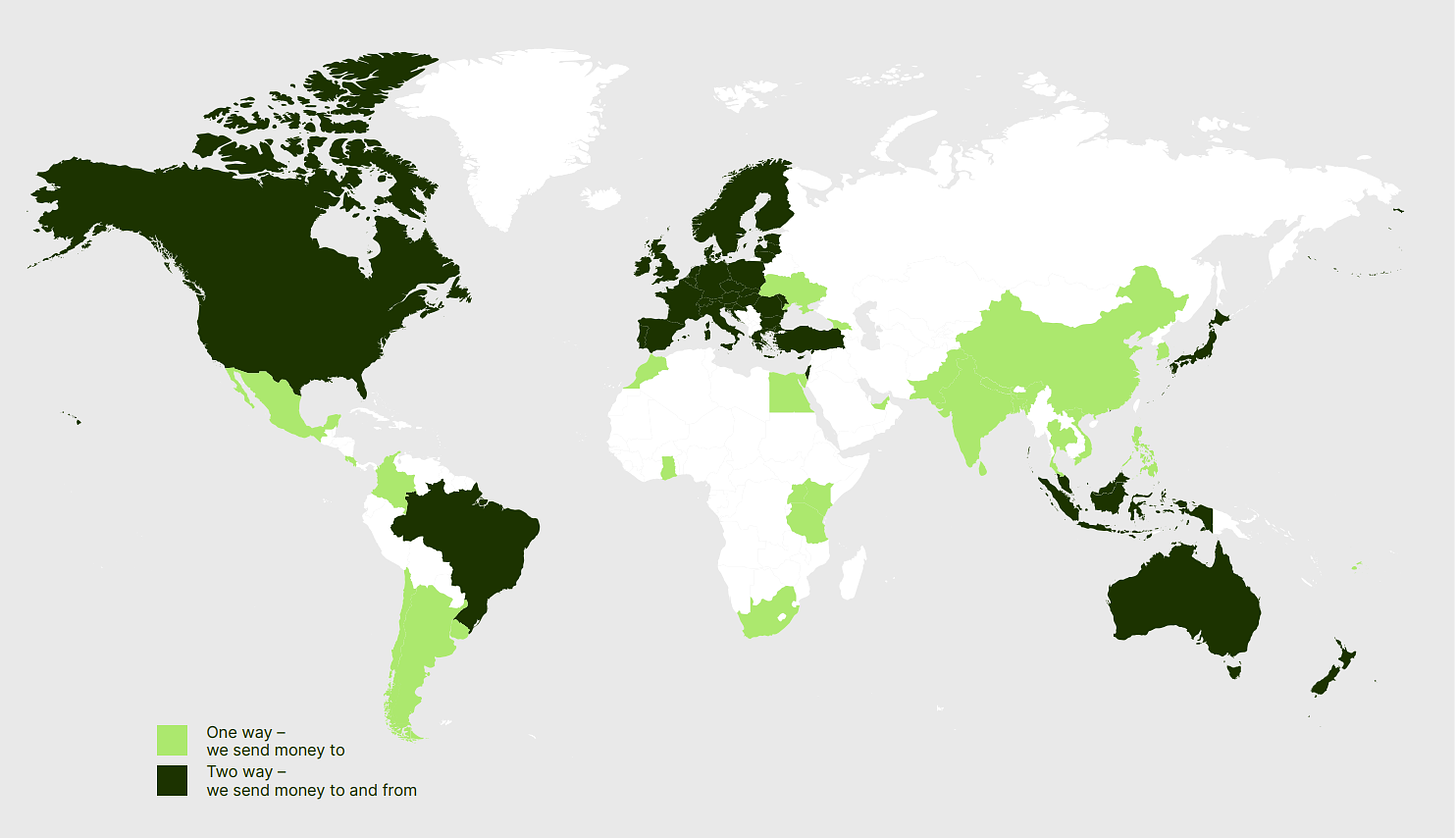

Moreover, most FSIs are based in just one country while one fintech, Wise, solved this problem on a granular level across 170+ countries of operation. Wise transfers money for consumers and businesses across thousands of corridors and can tag associated support costs to that specific pair of countries.

Because Wise is maniacal about reducing prices for customers, it has to fight for every cent that separates it from making its support groups redundant. Assigning those costs at the most atomic level enables those teams to own the resolution. Yes, a typical FSI might be decades away from such a level of sophistication, but the key is to start with one area and keep scaling. The coal mine is deep and dark, but the help desk and customer experience team could show the FSI the dangerous spots.

How Come Fintech Executives Forge Their Own Destiny While FSI Executives Fall Victim to Circumstances?

While fintech managers self-select to tackle challenging problems with innovative solutions, executives in traditional FSIs tend to operate within the status quo. They may still work long hours and acquire new skills, but they are primarily influenced by external factors. This creates a different kind of stress. For fintechs, the challenge is consistently expanding their market share. In contrast, for traditional FSIs, it's the uncertainty of how CEOs and investors might decide to alter an executive's role.

Individuals naturally gravitate toward environments that align with their preferences. I've personally resigned from a few jobs where top-down decisions about my role were the norm. However, many FSI executives prefer such an environment because they are accountable for executing strategic directions rather than setting them. These executives may struggle with the stress of the fintech world, where they would need to establish a direction and face aggressive challenges every step of the way. Moreover, imagine a CEO telling you that your idea is crazy but still allowing you to pursue it. What percentage of FSI executives would want that?

1. Three circumstances defining FSI executive professional life

FSI executives regularly get surprised by changes in direction: budget avalanches or budget cuts, capability outsourcing or insourcing, and of course, reorganizations.

Moreover, it's not like a typical CEO and Board hold strong convictions about the most effective approach to growing the business these days. Instead, they are driven by three factors:

What is trendy? (Cloud, AI, Blockchain);

What do institutional investors care about at the moment? (cutting costs, technology investment, ESG); and

How is the stock performing compared to peers? (better, on par, worse).

In a formula, the FSI strategy would look like this:

Trends * Investors * Stock = Strategy

The multiplier effect results in sudden moves. There is a growing list of FSI CEOs who have consistently been trendsetters rather than trend-followers, but they are still in the minority.

1. From empathy to iron fist

One of the most amusing examples has been Citi’s change in direction from empathy to a top-down reorganization (see this newsletter for more detail). After 2.5 years of “leading with empathy,” which coincided with a massive underperformance vs. peers, Citi's CEO completely changed her tone:

“Get on board. We have incredibly high ambitions for this bank and, the train, it’s gonna move fast,” Fraser told employees at a town hall meeting last week, according to people who heard the remarks. “So lean in, help us win with clients, help us deliver the changes, or get off the train.”

The irony is that the train has a pre-defined path and destination, while trends and investor focus change like the wind. That's why the change in strategy in many traditional FSIs is not deliberate. Not to keep beating down on Citi, but with the exception of a few people at the very top, no one at Citi was part of the discussion on how to start winning against Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan, or, even more fundamentally, what caused Citi to fall behind in the previous 2.5 years.

This is in stark contrast to fintech-grade practices where front-line teams have significant autonomy with only loose strategic direction from their leadership. Every significant change gets a heated debate to prove its potential P&L impact, and the CEO doesn't always win. If a fintech CEO told employees "to lean in or else," it would be a sign of a CEO failure who evidently didn't hire top talent. When a company does hire top talent, they would know better than the CEO how to be effective, as noted by Netflix’s co-founder:

Unfortunately, FSI executives are often not treated like adults by CEOs. Their opinions on strategy, even among top performers, are not welcomed by senior leadership. But are these executives part of the solution or the problem?

2. From spending bonanza to cost-cutting

The change in external circumstances often occurs much faster than 2.5 years. Let's take Truist, for example, which is the 6th largest US bank. Its CEO followed a recent trend of rapidly increasing technology spending, amplified by investors who bought into the mantra that higher technology spend creates a lasting differentiation. With the technology spending arms race underway (see this newsletter for details), Truist also invested in trendy initiatives like Cloud and AI:

“… moving more applications to cloud generates savings for the company. As Truist examines front and back operations, the company sees digitization and AI projects as important parts of the way it operates…”

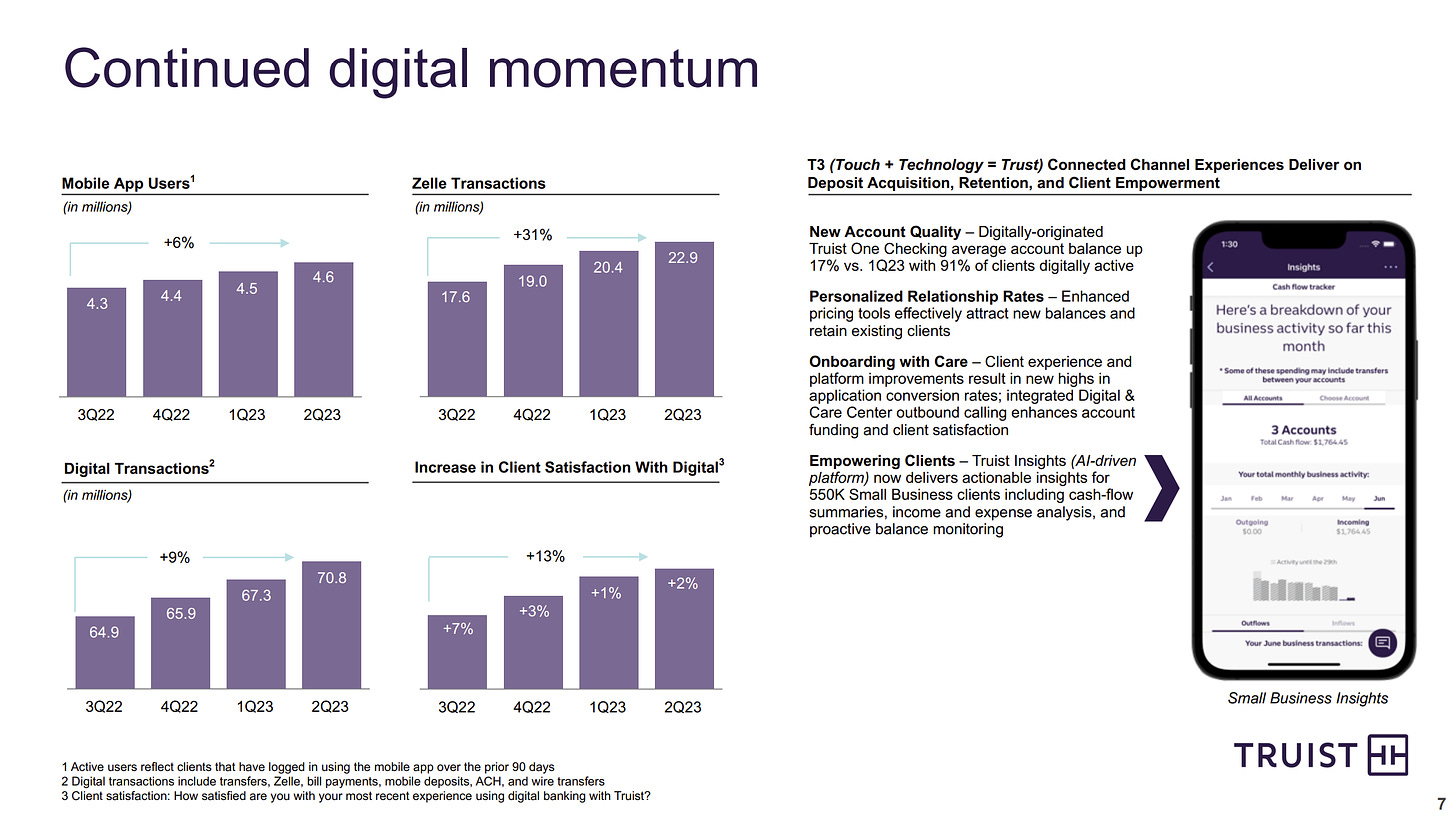

The bank's digital investments encompassed a virtual reality lab, a fintech acquisition, a new digital deposit product, and a chatbot. Until July 2023, the bank was fully committed to this trend, emphasizing its digital momentum in investor presentations.

Notice what is missing on the above slide? Correct, any direct connection to P&L impact. Like “pageviews” two decades ago, the number of users or the number of transactions are vanity metrics. We can look at the case of Charlie Javice, Frank's founder, and former CEO, as the epitome of pushing these vanity metrics to sell her company to JPMorgan Chase in 2021 - and JPMorgan buying into it. According to the press, Javice allegedly fabricated and manipulated Frank's data to make it appear as though her company serviced 4.25 million users, while in reality, the number was less than 300,000. Unsurprisingly, Jamie Dimon later stated that the Frank acquisition 'Was A Huge Mistake'.

The fact that JPMorgan caught the alleged fraud well after the acquisition was completed demonstrates how investors and CEOs are often gullible when it comes to following trends but not indefinitely. They can stay excited for a while as long as earnings are trending positively. But, similar to Citi's "leading with empathy," investor excitement tends to disappear when the business starts significantly underperforming.

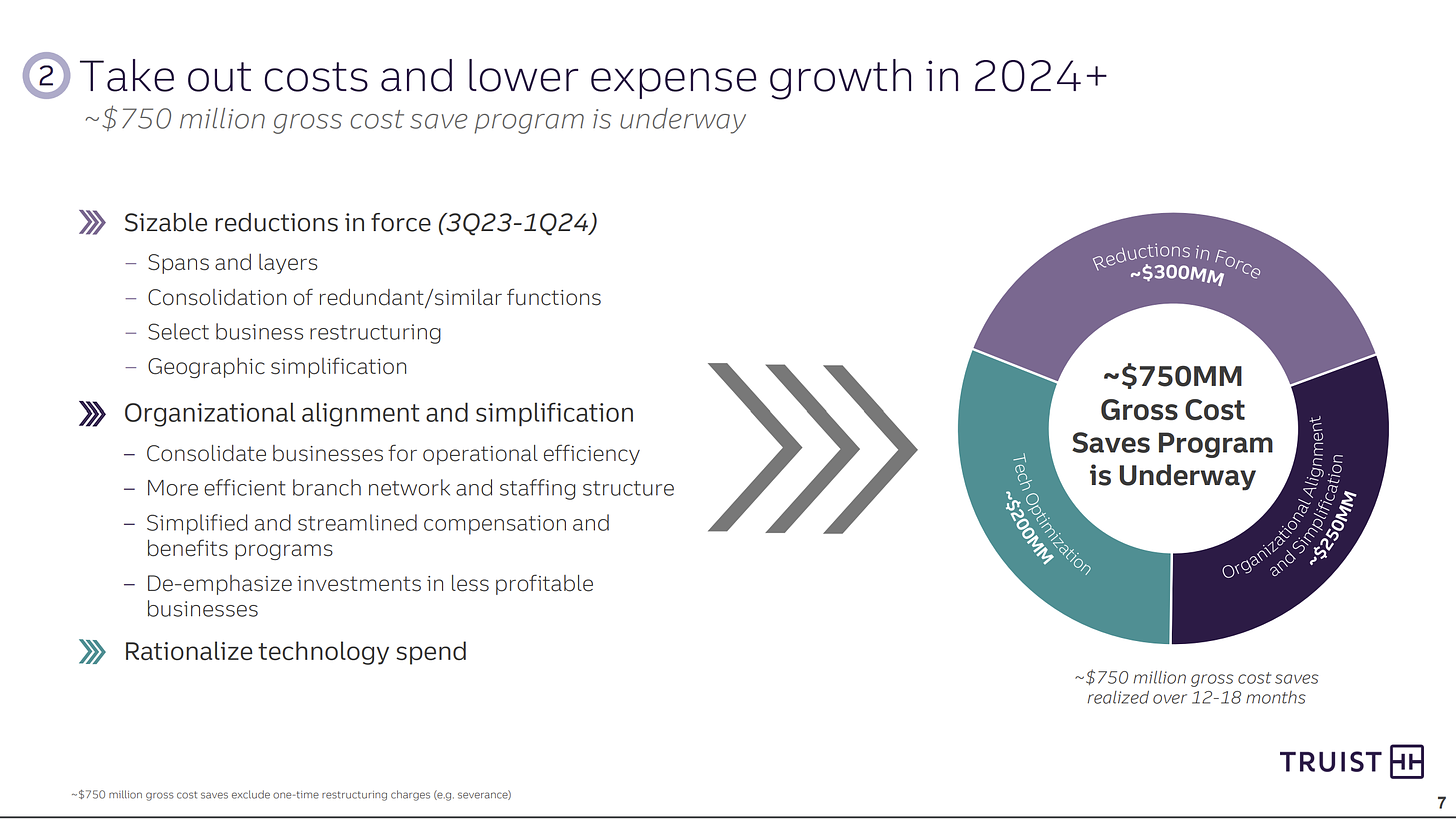

Citi's CEO had to announce radical changes after the stock dropped by 50%. In the case of Truist, the stock plummeted by almost 60% from its 2022 highs and remained at that level for nearly 6 months before the CEO was finally compelled to change direction.

In September 2023, Truist announced various measures including $200 million in “tech optimization” - the bank succumbed to external pressure and pivoted from digital momentum to cost reduction.

Without fact-based conviction in the profitability of its technology initiatives, the spending becomes arbitrary. Without involving executives in the decision-making, the success of any strategic effort gets randomized. In essence, for many FSIs like Truist, hope is the strategy, and FSI executives are usually the victims of those shifting winds.

3. The way out for FSI executives

FSI leaders who don't want to be victims of circumstances first need to develop their own well-considered, fact-based strategy. If they want to be treated like adults, they need to act at that level. This means resisting the temptation of easy approvals just because something is in-trend. If an executive unnecessarily expands their team with mediocre talent just because it's temporarily allowed, they can't complain about the CEO's lack of transparency in strategy. Why collaborate on strategy with someone who doesn't treat company resources as their own?

Once an executive defines such a profitable strategy, the CEO or their reports need to explicitly align on its fact-based P&L impact. It may not be the number of users, transactions, or applications moved to the cloud; it has to be a North Star metric for that FSI executive, either higher revenue or scalability. This way, if a Board member or a sell-side analyst asks why a particular area is not embracing generative AI, not consolidating divisions, or not reducing expenses, the response shall be, 'That would waste our company money and time, and we are pursuing more valuable initiatives instead.'

Finally, if an FSI executive develops a tight and impactful strategy but is told by the CEO to follow a superficial trend or investor wish instead, they should consider resigning to join a more deliberate FSI. Companies like JPMorgan, Capital One, Fidelity, Progressive, and others like them are not perfect, but your input would matter more, and the strategic direction would make more sense to you. A typical FSI executive has accumulated enough financial cushion to take a chance and not feel like a victim.