Digitally Transform Growth Divisions in Your FSI, Strategically Modernize IT Elsewhere

Also in this issue: FSIs Should Improve IT Vendor Management Last, Not First

Digitally Transform Growth Divisions in Your FSI, Strategically Modernize IT Elsewhere

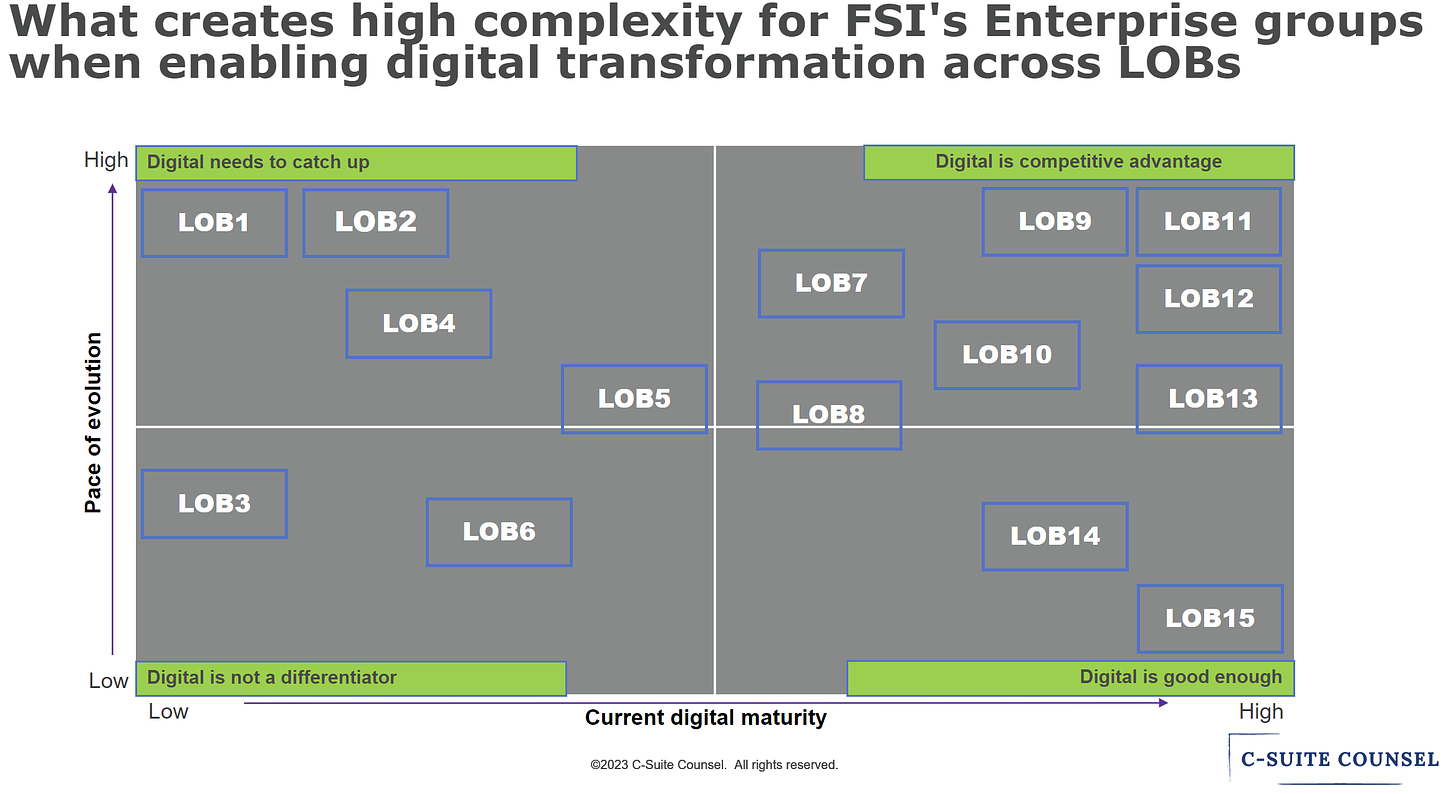

Real digital transformation in financial services isn’t a natural process — but it’s driven by a natural need. It demands that executives both level up their operating muscles and loosen their grip on control. At its core, the reason for transformation is simple: to capture more market share. The complication? Not every executive is chasing the same vision, and not every growth path depends equally on digital capabilities. This creates a surprising reality, even inside the most advanced FSIs: a 5–10 year gap in digital maturity between business units.

Capital One offers one of the clearest illustrations of this dynamic. It built its reputation as a lending powerhouse, particularly in riskier consumer segments. Capital One is globally known for its credit card business, inspiring both traditional competitors and fintech leaders like Nubank and Tinkoff. Yet within two decades, Capital One also claimed a top spot in the auto finance industry, rivaling century-old institutions like Ally Bank, a spinoff of General Motors.

More impressively, in 2023, Capital One Auto launched Navigator — a dealer platform built on a consumer-facing digital tool first introduced in 2015. It layers marketing, financing, and sales capabilities, demonstrating how a well-executed digital foundation can scale across new and complex markets.

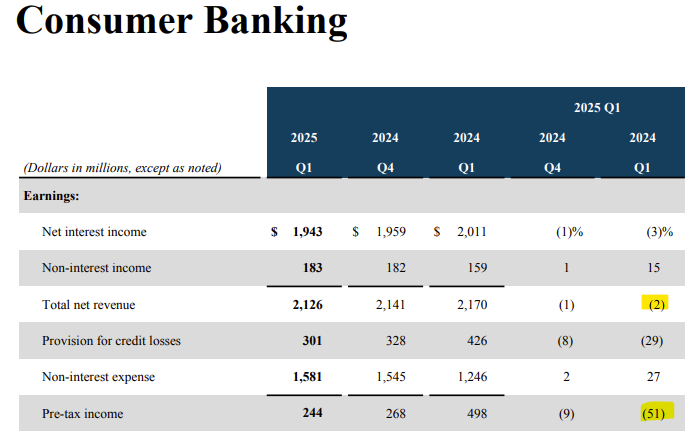

Capital One has a track record of making bold, sometimes risky, bets — and recouping them. Its focus on being best in class often means setting aside internal politics and requiring extra commitment from teams, including leadership. You might expect similar success across other divisions, such as Consumer and Commercial Banking. Yet in Q1, both units reported stagnant or declining revenue, with significant drops in pre-tax income.

Capital One needs its banking operations, if only as a cheaper source of funding — but the smarter long-term move would be to double down on its lending businesses while scaling the rest down to essentials. That, however, won’t happen under the current leadership. On a recent earnings call, CEO Richard Fairbank was still trying to position those divisions as a growth story, even as he acknowledged falling revenues and rising expenses in the same breath:

The clear divide in Capital One’s digital transformation priorities will come into sharper focus with its ongoing acquisition of Discover. What’s telling is where Capital One sees value. Much like its banking divisions, Discover’s product lines are unlikely to become high-growth businesses (its overall revenue grew just 2% in the first quarter of 2025). Instead, the expected return follows a traditional playbook: spend $35.3 billion on the acquisition, another $2.8 billion on integration, and target $2.7 billion in annual cost synergies.

That $2.7 billion breaks down $1.5 billion labeled as “expense synergies” and $1.2 billion as “network synergies.” The latter is straightforward: cutting costs by routing debit card transactions through Discover’s network instead of paying the MasterCard fee. The larger portion, though, rests on integrating Discover’s business and operations onto Capital One’s tech stack, banking on speed and efficiency to make the numbers work:

Most FSI acquisitions fail because they severely underestimate the effort required to bring a target onto the acquirer’s tech stack and wildly overestimate the savings. In Capital One’s case — with its lending divisions roughly five years ahead of Discover on the digital transformation curve — capturing “a lot of cost savings” would require taking over critical data and tech roles at every level.

FSIs have no choice but to embrace the heterogeneity of digital maturity across their businesses and align investments with realistic, business-specific upside. This mindset adds complexity for enterprise leadership, but the alternative is pushing divisional leaders into unnatural personal transformation journeys without a clear business case. A smarter strategy is to selectively modernize IT in those divisions, leveraging shared services where practical, while doubling down on digital in the units where rapid growth truly depends on it.

FSIs Should Improve IT Vendor Management Last, Not First

Deciding what to buy, outsource, or offshore in IT is a complex, multidimensional challenge with no clear playbook, even for leading traditional FSIs. The inherent tension in the C-Suite between efficiency and simplification versus business enablement is often heightened by leadership turnover and an evolving environment. On top of this, the presence of highly charming vendors further complicates the landscape, making it unsurprising that most FSIs regularly shift their strategic direction.

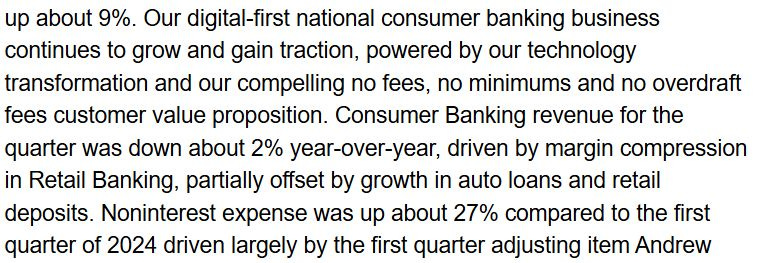

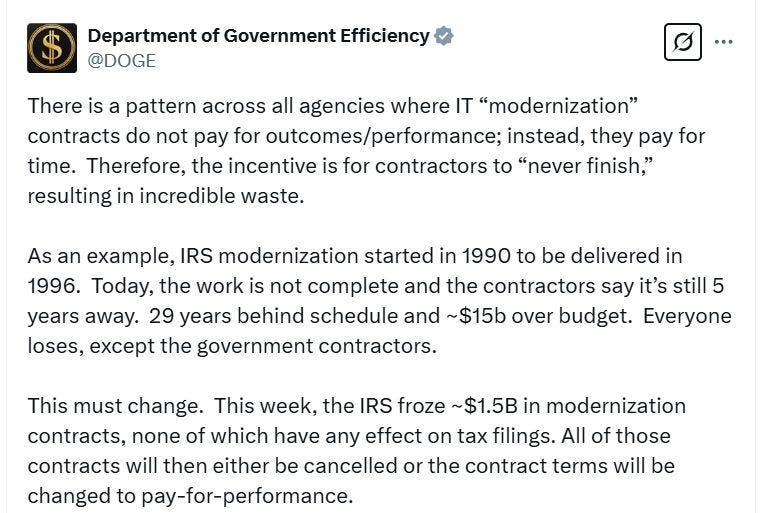

In the private sector, public acknowledgements of major mistakes are rare. However, the Trump administration's aggressive approach has brought transparency to seemingly irrational decisions made by governmental financial agencies. For instance, a group of PMO vendors convinced the IRS to sign a $1.9 billion contract for EPMO support:

Once Elon Musk’s DOGE team uncovered this contract, they promptly canceled it, correctly identifying the core issue — a misalignment of incentives with ROI. But it’s not as though digital natives or leading fintechs have perfected this either. Few, if any, anchor their buy, outsource, or offshore decisions to a clear, measurable ROI and structure vendor contracts around performance against it. It’s often the opposite: the most advanced players spend less time than traditional FSIs on elaborate business cases and vendor selection. They empower IT leaders to make decisions and pivot fast if outcomes disappoint or conditions shift.

In a typical FSI — much like in a government agency — the ROI of modernization programs tends to unravel under a few incisive questions. Vendors know this, which is precisely why they’ll resist any contract that ties payment to those hypothetical outcomes. The DOGE team will soon realize that even with an average IQ of 170, the real challenge lies not just in defining a credible ROI but in convincing vendors to bet on it:

Atul Verma, former CIO of BMO US Personal and Business Banking, recently reflected on lessons from three major banks that embarked on large-scale systems modernization efforts — only to pause or abandon them entirely. Among the core issues are weak business cases and an eagerness to heavily customize vendor solutions without having the internal talent or operating model to support them. No clever contract structure can compensate for those foundational gaps.

Even when a vendor agrees to an unrealistic pay-for-performance model, it’s often a sign of desperation for logos or market presence. In a recent CIO Online interview, National Life CIO Nimesh Mehta cautioned that with younger providers, “you end up almost building it for them,” and there’s a strong likelihood the vendor will get acquired before delivering sustained value:

“When you’re doing a legacy transformation that runs three to five years, you could have one, maybe two changes in ownership along that journey.” That requires carefully crafting contracts that ensure flexibility and leeway to manage those risks with smaller vendors, Mehta says.

Even vendors founded by former FSI executives, armed with seemingly innovative technology models, have struggled to scale. Companies like 10x Banking and Unqork commanded lofty valuations five years ago, as investors bet on technology alone as a disruptive force. Bold promises of 10x improvements in speed or 65% cost reductions grabbed attention, but critically, those outcomes were rarely embedded in vendor agreements or guaranteed in delivery.

When a vendor’s technology is genuinely innovative compared to incumbents, the central question becomes whether the FSI has the digital maturity in that specific business area to capitalize on it and whether it prefers to create the differentiation in-house rather than buy that capability. This nuance often limits product-market fit, resulting in a mixed and fragmented response from the broader industry.

Hence, it’s no surprise that core vendors continue to dominate. In US core banking, this dynamic has reached almost paradoxical proportions. Fiserv, with $20 billion in revenue and a $100 billion market cap, continues to post steady, profitable growth despite holding the lowest satisfaction scores among the top core providers:

The reason core vendors remain entrenched is simple — for all the industry talk about digital transformation and innovation, most traditional FSIs lack the ambition to create genuine differentiation through digital capabilities. While leading fintechs routinely prioritize in-house development, only a handful of the most advanced FSIs have built core applications that outperform top vendors. And even then, those internally developed platforms typically support only the fastest-growing business lines, while the rest of the enterprise continues relying on core vendors with little intention of changing that.

This selective in-house build strategy ties directly to another critical vendor decision: outsourcing and offshoring. The most digitally mature FSIs, like Capital One, recognized early on the risks of disrupting their high-growth divisions. When I worked with Capital One during my early years at McKinsey, they shut down an outsourcing strategy engagement the moment it became clear that the eventual transition would pause their release schedules by just a few weeks.

Other large FSIs learned that the trade-off the hard way. Only in recent years have many companies started insourcing and co-locating IT talent alongside digital teams, triggered by a long-overdue realization: the advanced phases of digital transformation are designed to build unique, defensible differentiation — work that is largely unmanageable for most vendors and poorly suited for remote setups. It’s a distant benchmark, but fast-growing fintechs like Revolut offer a glimpse of the target state: maximizing top-tier internal talent while sharply reducing reliance on outsourced support, especially in their high-growth areas.

The ultimate reason FSIs part ways with vendors is when they aim to turn their in-house core application into a platform they can commercialize, following the playbook of BlackRock’s Aladdin. Unfortunately, just as FSI CEOs finally stopped misusing the word “agile,” we now seem headed for a decade of them misapplying the term “platform.” On a recent earnings call, The Hartford CEO Chris Swift boldly claimed they have the best platform across all their businesses, while in the same breath acknowledging Guidewire as their core vendor for commercial insurance and claims:

“… we’ve been on a journey over the last ten, fifteen years of just making basic improvements into our core platforms in in all businesses… and then recently, we’ve launched a multiyear project, a seven year project to take all our data and applications to the cloud. So I think personally, we have the best platform in all our businesses. For personal lines, we have a modern SaaS based platform group benefits. We’ve modernized our all our platforms there and taking that to the cloud. And Guidewire continues to be our our preferred vendor both for administration in commercial insurance as well as claims.”

Guidewire is a solid vendor, but customizing its features won’t suddenly make it The Hartford’s unique platform. And even if The Hartford built its own platform across every business line, it’s unlikely to be the best in all of them — no FSI has pulled that off. Not even digital natives manage it: Amazon leads in cloud with AWS, but Prime isn’t the top streaming service. Google dominates search, but that success doesn’t automatically carry over to Google Cloud.

If The Hartford’s CEO is serious about having a best-in-class platform, he should focus on a specific segment of commercial clients and commit to building for them. If that segment begins to consistently grow by 20+% while becoming more profitable, then we’ll know Hartford truly has "the best platform" — at least in one area. The decision-making flow is always the same, with vendor management being the final step:

Business Model → Operating Model → Technology Model → Sourcing Model → Vendor Selection → Vendor Management