Disruption in Financial Services and Insurance Has Reached Terminal Velocity

Also in this issue: FSI Data Monetization Meets Regulatory Scrutiny

Disruption in Financial Services and Insurance Has Reached Terminal Velocity

One of the most striking aspects of digital transformation in FSIs is its highly variable impact across countries, product verticals, and client segments. In some niches, fintechs have become the new incumbents, while traditional players dismiss disruption concerns in others. For example, in the US, insurtech stocks remain 75–95% below their highs, while some European counterparts are already insolvent or on the brink of failure.

The original premise of disruption rested on startups being fundamentally more effective than traditional FSIs. While incumbents prioritized business models over operating or technology models, startups relied on superior operating effectiveness to maximize ROI with fewer resources. This advantage was expected to enable fintechs to pursue business models unattainable for incumbents, eventually pushing them out of business.

A recent example of this effectiveness gap played out in the UK’s C2C cross-border market. Around the same time, Atlantic Money, a newly formed startup, and HSBC, a global bank, entered the space. By late 2024, both had acquired around 10,000 repeat customers—but at vastly different costs. Atlantic Money did so with less than $10M in funding and fewer than 20 employees, while HSBC’s Zing spent $100M and hired 400 employees.

This disparity is even more shocking, considering Zing tried to undercut Wise by two-thirds in pricing, generating less than $50 in annual revenue per customer. The Financial Times recently reported that HSBC was actually only 25% short of its target for customer acquisition. In other words, the bank was willing to burn $100M for launch and around $50M annually to generate about $500K in revenue. Fortunately, HSBC’s new CEO—brought in to stop such foolishness—shut down Zing just four months into his tenure.

This superb level of fintech effectiveness is already forcing traditional players and even some fintechs to exit specific product niches, while others, like major banks and specialist providers, are stagnating for now. Will Western Union and Chase still compete in C2C cross-border within a decade? Even Amazon took 16 years to push Borders out of business, and financial services are far stickier.

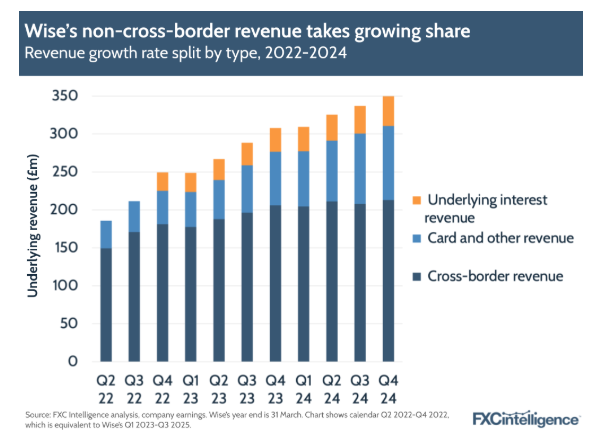

A broader disruption of banking incumbents remains an even more distant scenario. If it happens, Wise is a useful fintech to monitor for the forces at work, given its canonical scaling model—mastering one niche before expanding into adjacent revenue streams, which now account for nearly half its total revenue.

Such a disruption playbook becomes even more futuristic when considering geographical expansion and domination of multiple large financial markets. Whether it’s traditional banks like HSBC and Citi or neobanks like N26 and Cash App, retreating from global ambitions in developed markets seems the most likely outcome—even for seemingly tangential products. Will UK neobanks’ hopes for the US or Chase’s digital play in Europe face a different fate?

That is obviously predicated on whether a digital venture can maintain 20% volume growth after reaching the incumbent scale. This appears to be a terminal velocity number for leading fintechs from diverse products and geographies, like Cash App, SoFi, and Klarna. Some players, like Affirm and Remitly, are still growing around 40%, partially due to smaller volumes. However, eventually, most seem to coalesce around the 20% mark.

A decade ago, there was a small hope that fintechs could directly disrupt incumbents by automatically advising customers on how to use financial products with the most value for them and the least for FSIs. Today, this would be called an AI agent that switches products and negotiates for a monthly fee on your behalf. However, that intriguing business model has struggled to make a dent in incumbents. The latest casualty was a fintech called Cushion, which, after eight years, was only returning $2M in total annual refunds to its customers.

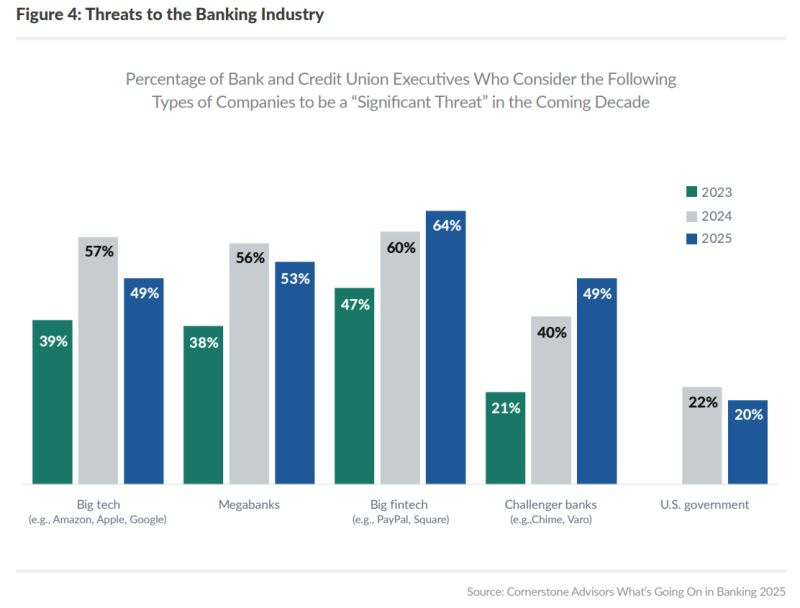

In addition to disruption by fintechs, Big Tech is still viewed as a significant threat. In a recent Cornerstone Advisors survey, US small banks and credit unions expressed concerns about Big Tech on par with challenger banks. This reinforces the repeatedly disproven myth that digital giants would one day aggressively compete with FSIs in a highly regulated market rather than continue selling them high-margin services without the extra hassle.

It’s easy to conflate disruption with growing the pie. Traditional FSIs' revenue could remain stable while disruptors continue growing rapidly because the latter serve first-time or riskier clients without regulatory impediments. A prime illustration is Tether, whose net profit in 2024 surpassed that of American Express. Yet, traditional FSIs aren't rushing to mint their own stablecoins.

The theoretical case for cross-border payment differentiation through stablecoins lies in the absence of a clear, winning fiat rail across the multitude of government, bank-owned, and credit card networks. As stablecoin expert Simon Taylor recently noted: "If I want to go from Visa -> FedNow -> JCB -> China UnionPay, stablecoins are perfect because they are U.S.-based and easily accessible."

The underlying argument is that Visa and UnionPay lack a direct link due to technology or cost barriers—barriers that stablecoins supposedly don't face. However, the more likely explanation is that those links are absent due to a lack of business demand or regulatory constraints.

We presume stablecoins operate in a gray area, as no cross-border payments crypto startup has disclosed details about their core repeat customer segment or total payment value. Or, at the very least, is there any stablecoin startup that compared itself to a fiat fintech for the same use case, explaining how stablecoins create material differentiation?

Instead, the most apparent value proposition seems to be untethered freedom—offering stablecoin issuers fiat money in exchange for privacy. Crypto firms invest in U.S. Treasuries, keeping the interest for themselves while enabling clients to pay for anything and anyone without regulatory oversight.

If traditional FSIs have a substantial footprint in a product where a fintech has reached terminal velocity, they should focus on doing hard things first. FSIs often deploy new digital features for customers not because of their business impact but because they are easier to implement and create the perception of digital maturity. Instead, focusing on real digital transformation would allow FSIs to compete with fintechs in effectiveness, which translates to passing more financial value to customers. This would help FSIs strengthen their position and sustain long-term relevance.

The side benefit of focusing more on transforming product economics rather than deploying more tangential features is that it makes it easier to ensure resilience. Experts often seize on every outage as an opportunity to blame legacy systems and push for fintech SaaS solutions. However, the recent multi-day outages at Capital One and Barclays made major news because they are exceedingly rare. The only exception in the past decade was DBS, which promoted itself as "more like a startup, less like a bank." Its 2023 outages, however, occurred at such an alarming pace that regulators banned some of its business and technology initiatives.

Traditional FSIs should also maintain focus on operating model transformation rather than doubling down on every novel technology hype. Instead of committing to "100%" or "X-first" technology initiatives like many FSIs, JPMorgan Chase has maintained a pragmatic approach to infrastructure, with no plans to move off mainframes for specific core processes. Darrin Alves, CIO of infrastructure platforms at JPMorgan Chase, recently told CIO Dive:

“We were methodical in our approach to cloud, so we didn’t go too quickly,” Alves said. “As we went, we learned that you need to be very thoughtful about which workloads make sense in public cloud.”

Certain banking applications align with on-prem capabilities, while others do not, depending on their function, data needs and scaling requirements.

In some cases, a modernized mainframe is the right call.

“We process more than 10 trillion dollars in payments a day on our systems,” Alves said. “While there are other systems that participate in that, the mainframes are the workhorse that do the bulk of the heavy lifting.”

Even the most novel technologies, such as Generative AI, are not causing rapid disruption. To everyone's shock, foundational GenAI modeling is becoming a cheap commodity less than three years after ChatGPT's launch. Like a cheap blockchain, a cheap GenAI model is impressive but still a solution in search of a problem.

Similar to tokens two decades ago or machine learning a decade ago, the lack of differentiation on the back end means that FSIs must differentiate by scaling profit-generating use cases. This requires a more advanced operating model. Traditional FSIs looking to slow fintech disruptors' terminal velocity must increase their surface area—much like a parachute slows descent by maximizing air resistance. Strengthening digital operating muscles makes FSIs more effective ecosystem partners while enhancing modularity to adapt to disruption threats.

FSI Data Monetization Meets Regulatory Scrutiny

Financial services and insurance are inherently risky businesses, but government intervention adds an entirely different type of risk. State Farm recognized that California's price controls prevented it from adequately pricing risks in certain areas, leading to a rapid exit from those regions while increasing its reinsurance coverage up to $4 billion. However, the exodus wasn't swift or large enough. State Farm's losses have already reached $8 billion following the recent LA fire.

FSIs also face constraints on offering different pricing for similar products. Capital One launched a separate high-yield product to attract new customers and instructed employees not to promote it to existing customers unless directly asked or to prevent attrition. This resulted in a $2 billion lawsuit from the CFPB.

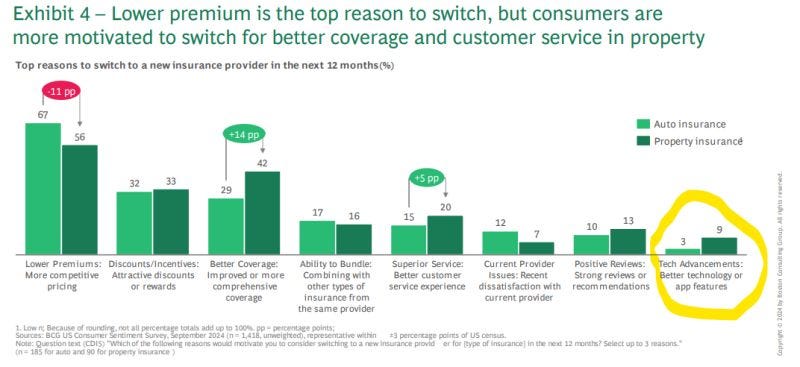

For nearly a decade, auto insurers have partnered with telematics data providers to price policies more accurately based on driving habits. This should benefit both safe drivers, who get fairer rates, and riskier drivers, who gain a clear incentive to improve. Even if a small percentage adjust their behavior, it could save countless lives.

Additionally, auto insurance is one of the fastest-rising categories in the CPI. Given the political focus on inflation, wouldn't regulators and state officials welcome measures that help contain costs?

Nope. The FTC and some states are suing insurers and telematics providers, requiring explicit customer consent for data sharing. Unsurprisingly, they offer no guidance on how to convince distracted drivers to share data that could double their insurance rates.

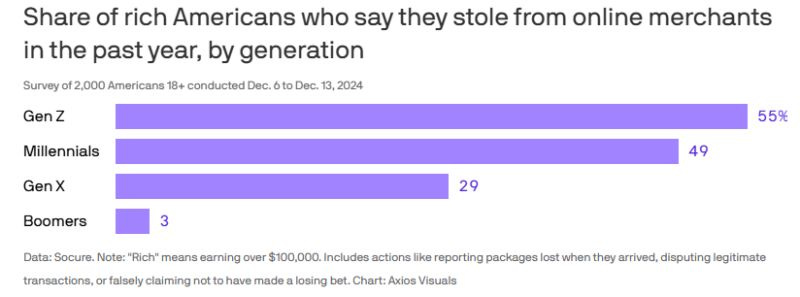

Prohibiting FSIs from using data through price controls or fines contrasts sharply with the leniency shown toward criminals exploiting financial or insurance products. Amid a surge in first-party fraud, where younger generations increasingly steal from online stores for fun, authorities prefer to hold banks accountable for all such fraudulent payments. Banks are expected to bear sole responsibility even when the fraud involves a fintech-issued card.

Public flogging and cutting off hands would certainly eliminate first-party fraud overnight, but that’s a crude comparison to prison sentences. Even in the toughest-on-crime jurisdictions, repeat offenders rarely get to prison—if they’re arrested at all—when theft amounts are small. Last summer’s viral check looting of Chase led to no prison time and just four lawsuits, with the bank requiring at least $80K in fraud to justify legal action.

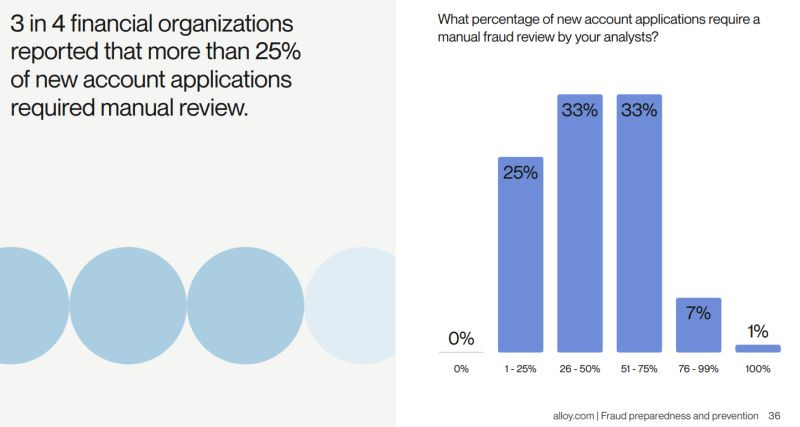

Instead of fully utilizing internal and external data to help law enforcement imprison repeat offenders, FSIs are increasingly forced to rely on manual reviews. The vision of a fully digital bank—or even a fintech—met with fraud, and fraud won.

In the U.S., FSIs' hope under the Trump administration is that the regulatory environment will focus on broader, proven impacts. Rather than fining FSIs for missing identity data or prohibiting the use of predictable information, the government could embrace a "let them cook" approach, allowing market forces to align risks and incentives better. Monetizing data would help FSIs grow and spur more competition for underserved consumers. The current alternative has clearly been ineffective.