FSIs Have the Digital Savvy to Model Risk If Only Politicians Let Them

Also in this issue: Leading FSIs and Fintechs Pursue Traditional and Digital Use Cases Alike.

FSIs Have the Digital Savvy to Model Risk If Only Politicians Let Them.

Digital transformation is like a delicate flower—while a skilled gardener (talent) is necessary, it cannot flourish without a sustainable environment. Conversely, in risky markets, the digital maturity of FSIs becomes less relevant. Consider the challenges a CEO of an FSI with risk-based products might face when deciding whether to enter a market under these conditions:

The market includes segments of astronomically high risk.

The government knows how to manage these risks but chooses not to act.

Prices are set by politicians, with changes taking a year to approve.

A government entity competes but also cannot charge market prices.

Underwriting data sets and model variables are dictated by politicians.

FSIs can be compelled to continue service even as risks drastically increase.

Even avoiding riskier segments, FSIs may be held financially liable for losses.

After catastrophic events, the government enables users to revert to the same risky conditions.

A strong CEO wouldn’t need much deliberation to avoid such a market. While FSIs routinely operate in high-risk markets in developing countries, they do so with the trade-off of being able to charge higher prices, compensating for the risks posed by low maturity and corruption in those jurisdictions.

It took more than three decades for U.S. property and casualty (P&C) carriers to connect the dots that California was becoming a risky market. By 2024, this realization culminated in a mass exodus of insurers. For instance, before canceling another large batch of policies, the largest U.S. P&C insurer, State Farm, requested a 39% rate increase for commercial apartment coverage from the California Department of Insurance but was granted only 23%. Already incurring losses, State Farm announced a complete withdrawal from the state. In response, California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara remarked:

Lara said his plan also involves changing the models insurance companies use to better assess risk and to lower rates for those who protect their homes. "The current modeling is a black box," he said. "We're going to change that to be much more transparent."

When the threat of auditing the underwriting model failed to yield results, the commissioner escalated by questioning the financial solvency of State Farm, the world's largest P&C insurer. He further threatened to investigate their books, as documented by the Los Angeles Times:

“State Farm General’s latest rate filings raise serious questions about its financial condition,” Ricardo Lara, California’s insurance commissioner, said in a statement. He said his department would use all of its “investigatory tools to get to the bottom of State Farm’s financial situation.”

Such constraints have made Los Angeles suburbs popular for building properties in iconic yet high-risk areas. Imagine living in one of the country’s most luxurious neighborhoods while enjoying some of the most affordable insurance rates. Artificially low prices encourage the purchase of properties that might otherwise be unaffordable and fuel massive development. This trend isn't unique to California—similar dynamics have unfolded in South Florida's coastal areas, which are regularly impacted by hurricanes.

There's a critical nuance: this system works only as long as the state doesn't face insolvency while its citizens' homes are repeatedly destroyed. Even in such a scenario, would federal politicians risk appearing unempathetic by refusing to bail them out? This dynamic incentivizes short-term political decisions that avoid addressing long-term risks. For instance, delaying improvements in water availability or allowing brush build-up persists as a strategy to placate California's influential environmentalist constituencies.

And what voter doesn’t appreciate a politician who helps them rebuild quickly—even if it means reconstructing the same homes in the same fire-prone areas?

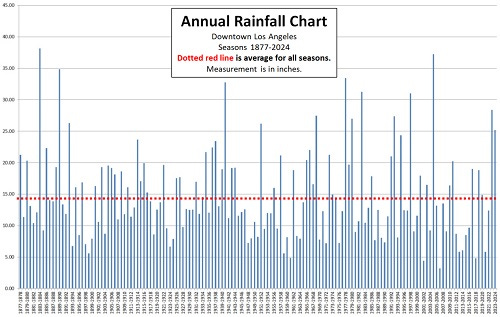

After all, these policies have consistently won the majority support of California voters since the 1980s. A politician must repeat "climate change" three times, and the issue is conveniently forgotten by the next election cycle. Among non-religious individuals, those words carry a weight akin to Deo volente, Insha'Allah, or B'ezrat Hashem. Ironically, the latest California fires occurred in January—during a polar vortex scare—and followed two seasons of heavy rainfall.

Such pandering incompetence poses little challenge for traditional insurance carriers, provided there are no price controls. They can model the impact of the next accidental or arsonist fire in an area filled with dry timber and empty reservoirs for fire hydrants without relying on digital transformation. In a recent CNBC interview, USAA’s CEO Wayne Peacock explained:

“You’ve got more expensive real estate, you have more real estate built … into the fire zones, and then there are all manner of conditions and situations in California that make that even more challenging,” he said.

“We’re seeing today that the cost of the built environment has gone up, and the risk associated with things like weather events has gone up,” he said. Peacock explained that aligning these factors with suitable insurance rates in California had become a challenge.

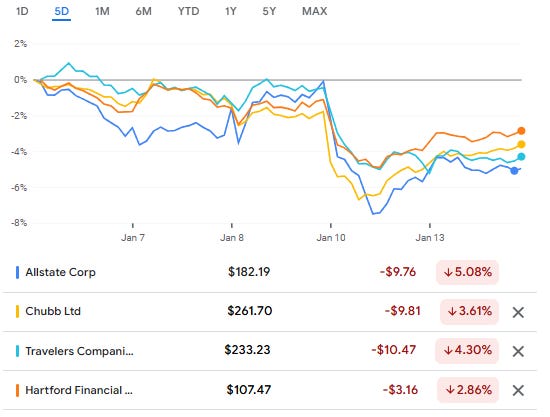

While pulling out of California saved large U.S. carriers billions, they still retained some policies in less risky areas. This means that some losses from the catastrophic fire might be unavoidable due to shared responsibility across all carriers in the state. As a result, the market capitalization of the largest carriers has already dropped by $1-5 billion each since the fire began.

If the system worked as it does in more effective jurisdictions, areas around Los Angeles that are periodically burned down or the frequent hurricane path areas around Fort Myers would be populated by wealthy individuals willing to pay astronomical insurance premiums. This becomes evident when no approved carrier, including government-backed ones, offers services, prompting a non-admitted carrier (also known as "unregulated" or "surplus line") to step in and fill the void. Here is one customer’s description of the parameters of his costly policy in Southern California:

“Here's how they cover it: my policy has a massive $105,000 deductible on wildfire damage, per covered loss. This means it's a per-event deductible (rather than per-year deductible). If I ever have wildfire-related loss, I'll have to pay the first $105,000 out of pocket before insurance even takes a look. And then if it happens again later the same year, the deductible resets. “

Since most people can’t afford these premiums and don't want to risk relying on a government bailout, they will move to less risky areas. Meanwhile, some consumers with more modest means absorb the risk, reflecting a growing trend. FSIs considering entering such risky segments would be better off applying digital transformation use cases to more sustainable markets.

Leading FSIs and Fintechs Pursue Traditional and Digital Use Cases Alike.

Bank of America's Merrill Lynch and the world's leading wealthtech, Betterment, launched consumer investment websites in 2010. Guess which one has 10X AUM? To the disbelief of some fintech experts, it's 120-year-old BofA. To add insult to injury: 1) Young adults represent a third of all investment accounts and half of guided ones, and 2) 80% of new accounts are opened after meeting an advisor.

BofA developed a bundle of multiple products that would offer multiplier rewards the more customers invest with the bank. And it's not like Merrill Edge's early years were fintech-grade. Achieving a somewhat seamless UX between the bank and Merrill took years and is still somewhat clunky. The difficulty of such integration is tangentially evidenced by only one other bank, U.S. Bank, launching a similar product more than a decade later. However, as our newsletter often discusses, the right business models consistently outperform suboptimal operating and IT models.

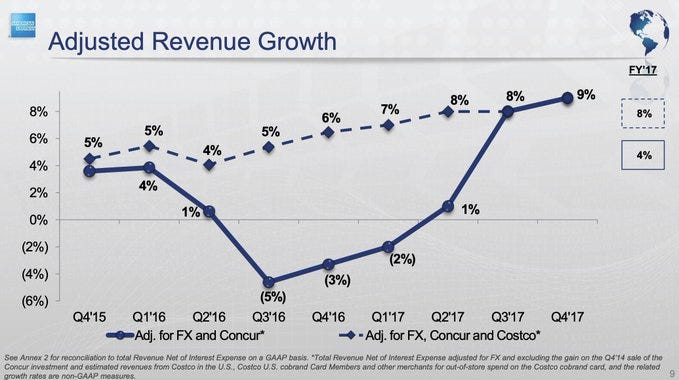

BofA's approach was innovative at a time when other large banks were engaged in bidding wars for co-brands. The most notorious case from that era was American Express's Costco partnership. It took Amex's C-Suite a decade of convincing to enter the credit card space while giving Costco an unheard-of interchange discount. The product became an immediate hit, but Costco was the most formidable negotiator yet. After comparing Amex to ketchup didn’t result in a better renewal offer, Costco shopped around—securing an irresistible offer from Visa, marking the first breach in Citi's foundational relationship with MasterCard.

As recently uncovered by fintech expert Jevgenijs Kazanins, this chart illustrates the profitability of that co-brand product - the hit to Amex revenue growth has lasted for a year and a half:

Not worrying about perfect conditions from the get-go is more common among traditional FSIs than many think. The last decade of massive attempts has resulted in an illustrious graveyard. However, such common failures don’t seem to diminish the digital risk appetite of large FSIs. Chase’s billion-plus-dollar bet on becoming a top-5 digital bank in Europe is the best-known example, but even Wells Fargo is not far behind. True to the ethos of "move fast and break things," the bank first launched the most daring co-brand card in history, Bilt, and only then hired top-notch executives to oversee it.

Moreover, Wells Fargo's approach is less risky since it relies on a partner, Bilt, for digital innovation and acts mainly as a traditional bank in the background. It might be losing $10 million per month, but there are executives with proven expertise in getting co-brand card programs back on track.

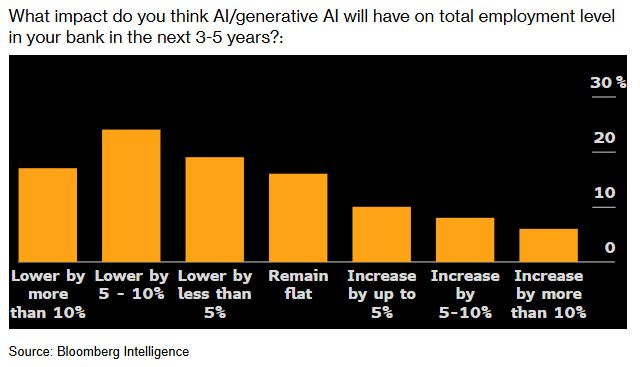

Winning market share through organic digital transformation is much riskier due to the numerous unknowns involved. When Bloomberg recently surveyed CIOs and CTOs of global banks about their expectations for Generative AI’s impact, the responses were underwhelming. With a common target of spending 1% of revenue, CEOs likely expect a substantial improvement in the top and bottom lines in the short term. However, on average, IT executives expected only a 5% workforce reduction within 3-5 years.

One of the reasons behind such hesitation is the uncertainty surrounding novel technology. Even after over a decade of using the cloud at scale, there is still debate over how exactly it generates profit, with some FSIs partially repatriating capacity back on-premise. Generative AI is even riskier. A couple of years ago, many FSI executives bought into the idea that its imminent power would surpass all existing bottlenecks, such as human processes and siloed unstructured data. So it’s not surprising to see more memes from operators who have been struggling to generate value from GenAI:

Despite prodding from digital experts, smaller and even mid-sized FSIs remain cautiously behind in pursuing digital transformation, especially in use cases relying on novel technology. In my conversations with C-Suite executives from these FSIs, they understandably conflate digital transformation with IT modernization. There's little point in aiming to transform operating models into cross-functional value streams and enabling platforms until their IT systems can effectively scale internal product teams. Jennifer Quinn, Vice President of Digital Services at Edwards Federal Credit Union, recently offered a typical definition of digital transformation from this FSI segment to CU Insight:

“… digital transformation is a comprehensive, ongoing effort to evolve our operations, lending, and member services by leveraging technology. We are integrating more digital tools and platforms that enable us to serve our members better and deliver greater value, efficiency, and convenience. This also includes making our staff’s jobs more manageable by reducing friction or streamlining processes through these digital transformation tools.”

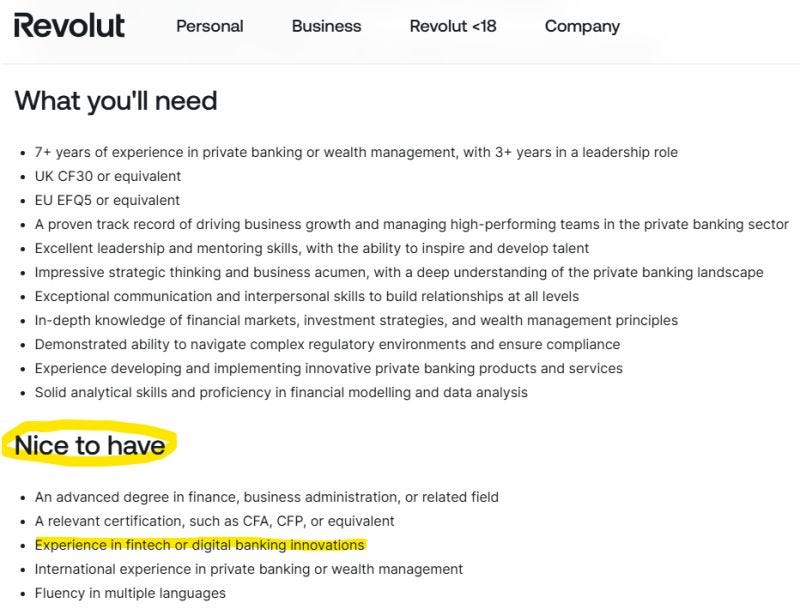

While FSIs are pursuing traditional and digital paths to generating profits, some leading fintechs are doing the same. Revolut, the ultimate fintech blitzscaler, recently announced its expansion into private banking. Rather than joining the banal digital or GenAI wealthtech hype, Revolut wisely sought a Head of New Business with a traditional background. Digital acumen was mentioned as merely a "nice to have."

Most executives who have successfully led transformation will attest that it’s an excruciatingly hard process. Therefore, it's unsurprising that some FSIs prefer to rely on every possible gimmick rather than transform their operating model into cross-functional teams. In situations where digital transformation makes obvious sense, FSIs should prioritize those specific use cases without compromising ongoing lucrative opportunities tied to traditional business models.