FSI Discrimination Against Consumers and Businesses Is a Sound Business Practice, Not a Government Conspiracy

Also in this issue: Is Printing Digital Money the Best Use Case for FSIs?

FSI Discrimination Against Consumers and Businesses Is a Sound Business Practice, Not a Government Conspiracy

Every year in the US alone, nearly 30 million reports are filed on suspicious activities by consumer and business clients potentially linked to financial crimes. Meanwhile, 30-40% of staff at leading fintechs like Revolut and Wise focus on detecting, investigating, and reporting financial crimes and compliance with the regulations. Globally, FSIs spend $200+ billion annually on compliance. Are those efforts making a difference?

“Around a third of our global team is dedicated to fighting financial crime and helping to ensure that we are in compliance with the requirements of the more than 65 regulatory licences that we maintain around the world,” Wise said.

So far, crime seems to be winning. Over half of FSIs report rising consumer and business fraud. The recovery of $10 billion in corruption proceeds since 2010 sounds impressive, but it pales in comparison to the $1.6 trillion laundered annually. Moreover, questions have arisen about whether this massive compliance effort, led by Western governments, is primarily aimed at punishing populist-right politicians and entrepreneurs. These concerns went viral recently when renowned entrepreneur and investor Marc Andreessen, on the Joe Rogan podcast, accused the CFPB of de-banking businesses with politically opposing views.

While Marc got many details wrong, like any good conspiracy theory, the accusations weren't entirely baseless. Most decisions within FSIs are driven by the C-Suite, whose aspirations often revolve around being part of the 'enlightened' class. About a decade ago, addressing the imminent climate catastrophe became fashionable, prompting FSIs to establish sustainability roles and initiatives to combat global warming. After George Floyd’s death, addressing racial inequity took center stage, leading to the creation of DEI groups and anti-racist training programs. More recently, it became trendy to view right-wing populists as potential Hitlers, resulting in FSIs canceling the accounts of certain politicians and even their family members.

Once a trend fades, FSIs quietly unwind these PR-driven initiatives. Politicians like Trump and Farage had their accounts reinstated. American Express no longer holds events claiming capitalism is racist. JPMorgan Chase has pulled back from performative climate frameworks, with its global head of sustainability reintroducing climate finance discussions regarding real ROI.

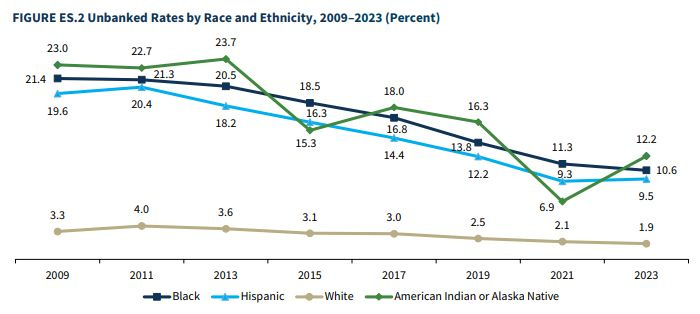

Beyond the FSI C-suite executives' eagerness to align with the elite zeitgeist, they primarily focus on running a profitable business. Unfortunately, some consumers and businesses are often seen as "more trouble than they’re worth." Despite public concerns about the unbanked, no major traditional bank or neobank is investing significant efforts to bank homeless in the Bay Area or blacks living below the poverty line in Alabama and Mississippi. This isn't due to executives disliking the poor or minorities, but because the ROI is likely to be negative.

Being unbanked is a symptom of poverty, not its cause. The unbanked rate has halved over the past decade, not due to digital banking or fintech innovations but because median household income rose by 20%. However, if an FSI indeed views addressing the unbanked as a charitable focus rather than a PR campaign, it must target minorities living below the poverty line. The real question is: how much can an FSI make from this segment compared to the effort required to get them banked?

I first encountered the term "debanking" (or "de-risking") a decade ago after founding SaveOnSend. In the remittances industry, the de-banking of money transfer operators (MTOs) was a common issue, particularly affecting the smallest MTOs, crypto players, and high-risk destinations like Somalia or the Cayman Islands. However, even for the most prominent money transfer specialists, it remains a significant concern. While most of these companies have a primary banking partner, they also maintain business relationships with other major banks as a precautionary measure.

You would think that any bank would be eager to have Western Union or MoneyGram as a client, but the reality isn't as exciting. If these firms were heavily involved in underwriting or M&A deals, it might be different, but the regular fees for banking services often don't justify the added complexity. Here's how the head of financial services & fintechs at a top-4 US bank described the risks of holding a correspondent account for one of the large remittance firms:

“Our bank conducts an annual, two-day, dedicated compliance due diligence with AML, Compliance, and Payments committee members, as well as stakeholders from Risk, Banking, and Cash Management teams. This is necessary because providers, at times, knowingly or unknowingly misrepresent the types of money transfer accounts they serve. Even when discussing the renewal of credit commitments, a large portion of our banking peers usually decline to participate due to potential regulatory concerns.”

The same logic, though on a smaller scale, applies to consumers exhibiting seemingly risky behavior. If someone consistently deposits $9K in cash every month, why would a bank invest days or weeks investigating whether it’s for legitimate reasons or to avoid taxes or overseas capital controls? The same applies to an entrepreneur seeking to scale businesses in sectors like guns, gaming, adult entertainment, or recreational drugs. Statistically, enough of those ventures are likely engaging in nefarious activities, and the potential profit for the bank isn’t worth the risk.

As a result, traditional banks and neobanks find themselves in a lose-lose-lose situation: they’re pouring enormous resources into staying compliant while financial crime continues to grow, and they’re being held accountable by the media and politicians for both this and for not banking every consumer and business. This hostile environment is amplified even by supposedly knowledgeable media outlets like the Financial Times, which recently published an investigative report on Wise’s AML lapses. However, it uncovered an old story about a one-off proof of address requirement in a small jurisdiction, with no fines involved.

Even worse, regulators are not telling FSIs and neobanks who to unbank but are scrutinizing whether any particular consumer or segment is being excluded, effectively forcing banks to conduct a massive effort to prove the negative. Most people, including podcast hosts and technology experts like Joe and Marc, don't fully understand these drivers. While it's tempting to view FSI leaders as cruel and cowardly, like the Wicked Witch of the West, they are often misunderstood and primarily act to preserve their institutions.

Is Printing Digital Money the Best Use Case for FSIs?

Our newsletter often discusses how every ambitious FSI CEO dreams of building a platform like BlackRock’s Aladdin. However, it is tough to create a software solution that your competitors would be willing to pay a premium for—and that their developers would find elegant. But what if there was an easier way for FSIs to make money? What if FSIs could print money? Some, like PayPal, already do.

Half a billion might not seem like much for an FSI like PayPal, with its $80+ billion market capitalization, but it’s essentially free money. Like holders of any currency, there's no expectation of intrinsic return—just the belief that the money is safe and widely accessible. Moreover, unlike the trillion in coins issued by unregulated entities, PayPal holders have a better chance of recourse.

The beauty is that anyone can print digital money with thousands of active cryptocurrencies. Ripple launched XRP in 2012, promising to revolutionize global payments. Despite numerous partnerships with banks and grandiose claims, it has yet to disclose revenue. Moreover, it paid FSIs like MoneyGram to generate liquidity. None of that seems to matter to XRP buyers—it is now the third-largest cryptocurrency, with a market capitalization of over $150 billion, and Ripple is about to launch a stablecoin.

The fourth-largest cryptocurrency is Tether, frequently used for financial crimes and sanctions evasion, and is only now hiring heads of AML in key regions. The only well-known case of a company not being allowed to print money is Facebook. For years, Facebook struggled to scale payments until spinning that group off in 2018 into a crypto venture called Libra, later rebranded as Diem. It tried to launch in the US, then Switzerland, then back to the US, before giving up by early 2022.

Facebook made two categorical errors that FSIs could easily avoid. First, it tried to portray the endeavor as separate from Facebook, which no one believed. Second, it created a massive coalition of 28 corporate backers, including Visa, PayPal, Stripe, and other heavyweights in the financial and digital worlds. With that and Facebook’s already sketchy reputation, US and European regulators blocked the effort with bipartisan support.

The good news for FSIs is that they don’t need to overthink the value proposition. Since Bitcoin’s inception, almost all cryptocurrencies have had a similar pitch: arguing that fiat-based payments are slow and expensive, which negatively impacts unbanked and small businesses in the world’s poorest countries. In contrast, free and instant crypto-based payments are marketed as a game changer for the most unfortunate people.

The disconnect between printing money for well-off holders while portraying currency as a game changer for the poorest consumers was strikingly illustrated when PayPal launched PYUSD in its money transfer subsidiary, Xoom. Instead of simply replacing the fiat rail with PYUSD, Xoom customers had to select a stablecoin rail as a payment method. If transferring money via PYUSD is much faster and cheaper than SWIFT and ACH, why wouldn’t PayPal automatically replace those fiat methods with stablecoin for all transactions? It’s not like consumers know or care about which back-office protocols an FSI uses to provide financial or insurance services.

The answer is straightforward—PayPal does not want to cannibalize its existing profit margins, as Xoom is usually among the more expensive MTOs. Instead, it hopes to attract additional customers and have them keep funds in PYUSD rather than cashing out immediately, offering PayPal free capital. Furthermore, such PR efforts create the perception of a genuine use case for their stablecoin, making it a worthwhile investment even for consumers and businesses with no remittance need.

Additionally, there seems to be some crypto usage among low-income people, just in case regulators ask for proof that the currency solves any problem. Around 200,000 US households with below-average income used crypto at least once in 2023 to send or receive money.

Finally, if your FSI is concerned about government officials disliking a private competitor for its CBDCs, fear no more. In countries like the US, government bankers still don’t fully understand why they need to launch them, and there is solid political blowback when they do. Even in China, which is supposed to be ahead of everyone with CBDCs, there is still no clarity on the benefits beyond what could already be done with their famous super apps. Recently, China’s head of CBDC design was caught accepting bribes—of course, not in digital yuan, but in private cryptos.

So, what’s stopping your FSI from printing digital money?