Why Can't FSIs Be as Effective as Startups?

Also in this issue: If Higher Digital Spending Doesn't Differentiate an FSI, What Does?

Why Can't FSIs Be as Effective as Startups?

"Investment has been cut, and the most senior executive who sponsored the digital subsidiary left the company," shared an insider in a $5B FSI that ventured into a startup-building business a couple of years ago. The warning signs were evident from the beginning - the subsidiary launched five products initially and was led by a large team of executives from the parent company. Despite a decade of consistent lessons from such failures, traditional FSIs can't seem to adopt a simpler approach: a small team of 10X employees, a minimalistic budget, and a focus on one use case.

HSBC launched its cross-border money transfer fintech, Zing, in early 2024 and already has 80 employees. For comparison, Telegram, with nearly a billion monthly active users and offering businesses and payment services, has only 30 employees. Granted, they are not a regulated FSI. Wise, Zing's main competitor, had 80 employees just three years after its launch when it was processing around $100 million per month (known as Transferwise at the time). Atlantic Money was launched less than two years ago and is already handling around $50 million per month with fewer than 20 employees. Why couldn't HSBC achieve a launch similar to Wise or Atlantic Money, considering they are all London-based competitors targeting the same product and customer segment?

Two years of preparations

The problem began two years earlier when HSBC initiated preparations for launching Zing, codenamed project "Marco Polo." It conducted research that yielded a surprising finding: there were no top players in cross-border money transfers offering satisfactory customer experiences.

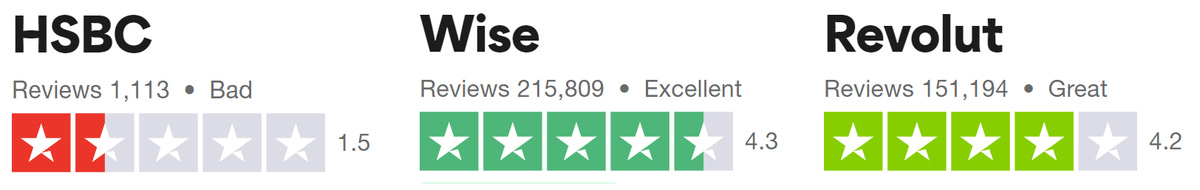

This conclusion was odd because, by 2022, the UK market had become highly competitive between incumbents and fintechs for this product niche. It is more likely that HSBC confused its own customer perception of the bank's cross-border product with how customers of leading players felt about their products.

Setting aside the erroneous research conclusion, what has taken HSBC two years to launch a clone of the simplest financial product with plenty of partner solutions? A recent interview with HSBC's Zing CEO, James Allan, sheds some light on this:

Zing’s offerings have been carefully crafted to ensure they can attract “customers that don’t have a relationship with HSBC”. Even the colour and shape of the logo were carefully considered to catch the international clientele it’s aiming to poach off its rivals.

“We even had dialogues about the way that the word was written,” says Allan. “The lines [in the logo] are meant to point towards forward direction and movement.”

I worked at Bridgewater Associates when it was constructing a new trading floor, with months spent debating the texture and color of the carpet. In a traditional FSI, executives tend to engage with non-revenue-generating matters because their compensation and the company's performance are stable. Why not spend months debating the line on a logo and still receive an HSBC salary? Feast your eyes on the result:

In a fintech, the culture is lean and mean - founders and initial hires often receive minimum pay in the first few years and might not even have windfall gains. Investors closely monitor progress every quarter and will consider selling off or shutting down if the growth curve doesn't materialize as expected.

Besides the logo debates, what else could be occupying 80 people and necessitating 2 years of preparation for a new subsidiary of a traditional FSI? Of course, HSBC had to launch multiple products to serve multiple destinations in the first few months since launch. Customers could hold money in 10 currencies and send them in over 30 currencies.

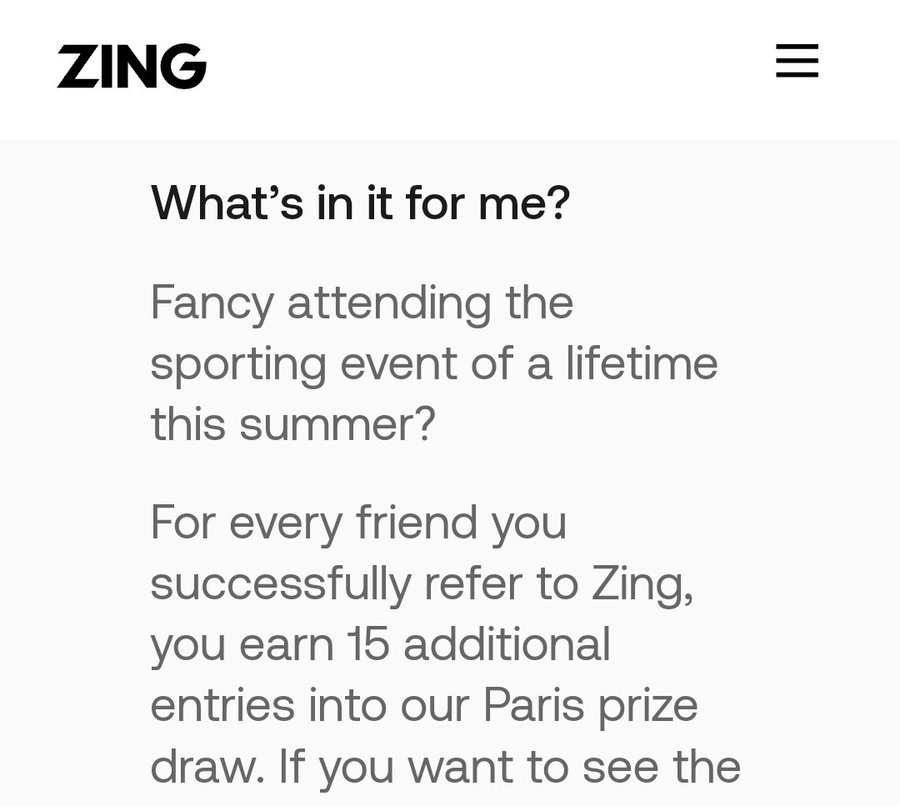

One of the most popular consumer acquisition channels among fintechs is referrals. Assuming a "wow" product, this offers extra incentives to customers who love it to spread the word within their network. For example, players like Wise pay £75 for 3 referrals. However, that might be too simple for a traditional FSI. HSBC's idea to incentivize virality is to offer a hypothetical entry into a prize drawing for a trip to one specific country:

If your FSI is considering launching a startup, keep the above learnings in mind and begin by addressing a fundamental question: can we differentiate ourselves from leading players in data and models? These are the only sustainable competitive advantages for a traditional FSI.

Unfortunately for HSBC, while it conducts over $10 billion in annual money transfer volume for its customers, that represents only a fraction of what leading players like Wise achieve. Moreover, Wise has an additional decade of proprietary analytics. If HSBC were as effective as a fintech, it would have targeted an easier market to disrupt.

If Higher Digital Spending Doesn't Differentiate an FSI, What Does?

The singular reason for digital transformation is to enhance FSI's operating muscles to be more effective than competitors at scaling digital capabilities. This is typically done in a piecemeal fashion, focusing on specific opportunities to generate high ROI and P&L impact. However, being effective does not guarantee indefinite high growth. Some customer segments or products may be too risky, burdened by high regulatory requirements, or facing intense competition from well-funded rivals.

For example, SoFi, one of the most intriguing consumer finance companies with a technology platform business set to generate half a billion in revenues, has seen its stock plummet by over 70% from its highs. Despite a high digital maturity, SoFi’s revenue growth rate has been decreasing by 10-20% per year:

Fintechs recognize this phenomenon and are adaptable in their spending. Unlike traditional FSIs with stagnant budget allocations, startups could flex the relative focus by a factor of two. Money is either preserved or rapidly reallocated from lower-priority areas (e.g., Technology & Data Analytics in the case of Affirm).

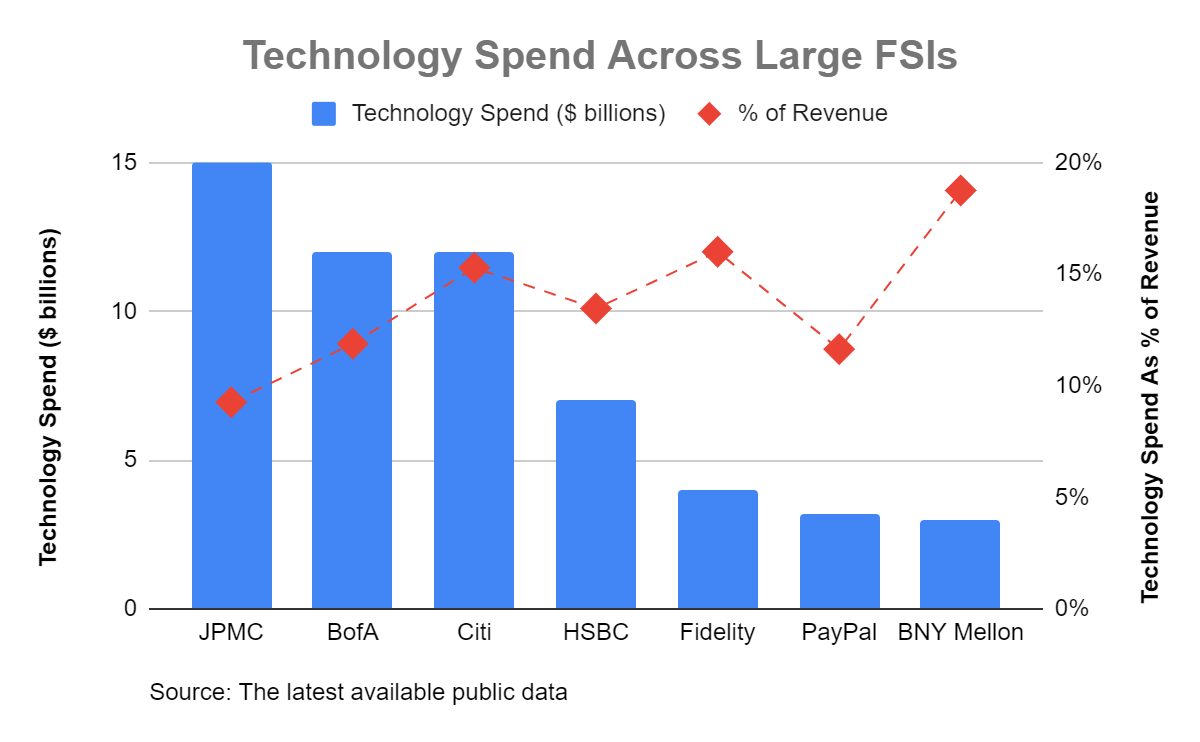

Spending more on technology just to satisfy the hype of digital transformation does not make sense for leading FSIs either. Their relative spending as a proportion of revenue does not correlate with their effectiveness or guarantee future P&L growth.

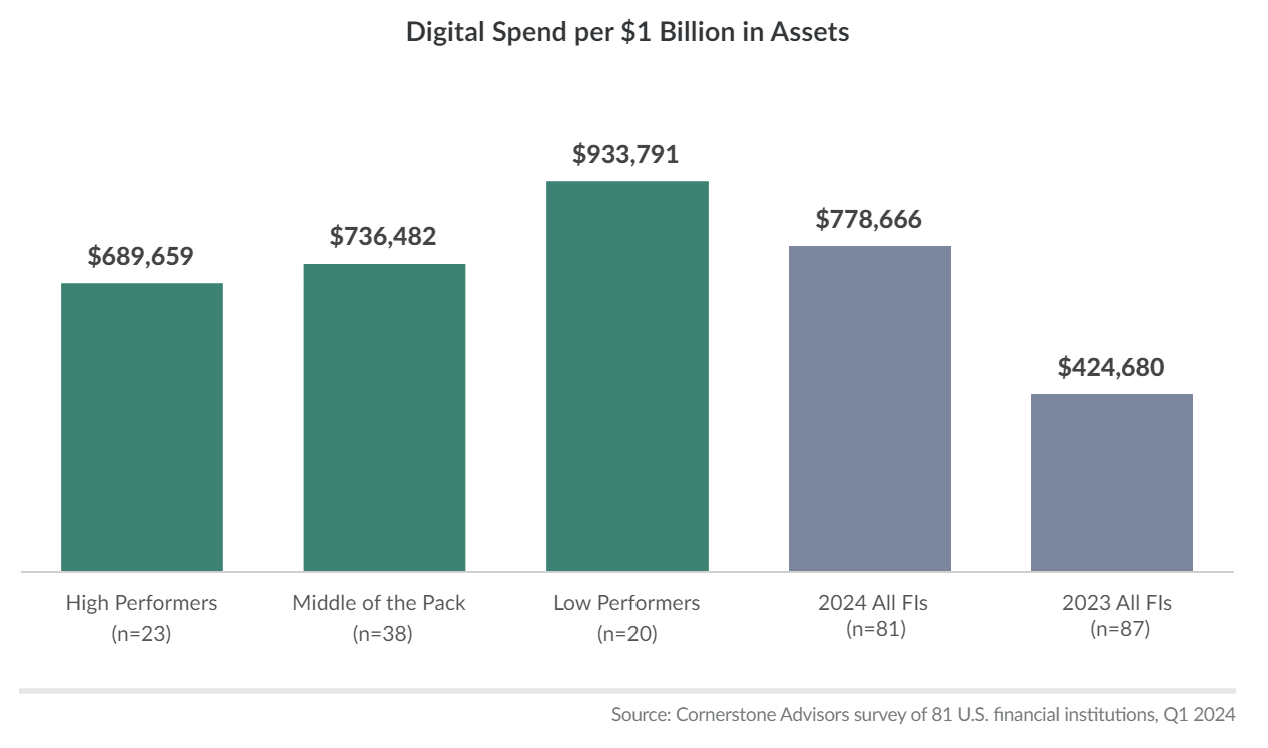

Even among smaller, lower-maturity FSIs, the same lack of correlation holds, as confirmed by The 2024 Digital Banking Performance Metrics Report by Cornerstone Advisors. Among smaller banks and credit unions, lower performers were spending 25% more on digital. Even higher digital usage by consumers did not mean that an FSI in the study was more effective. The only metric signifying higher performance was the average number of monthly P2P transactions per active P2P user.

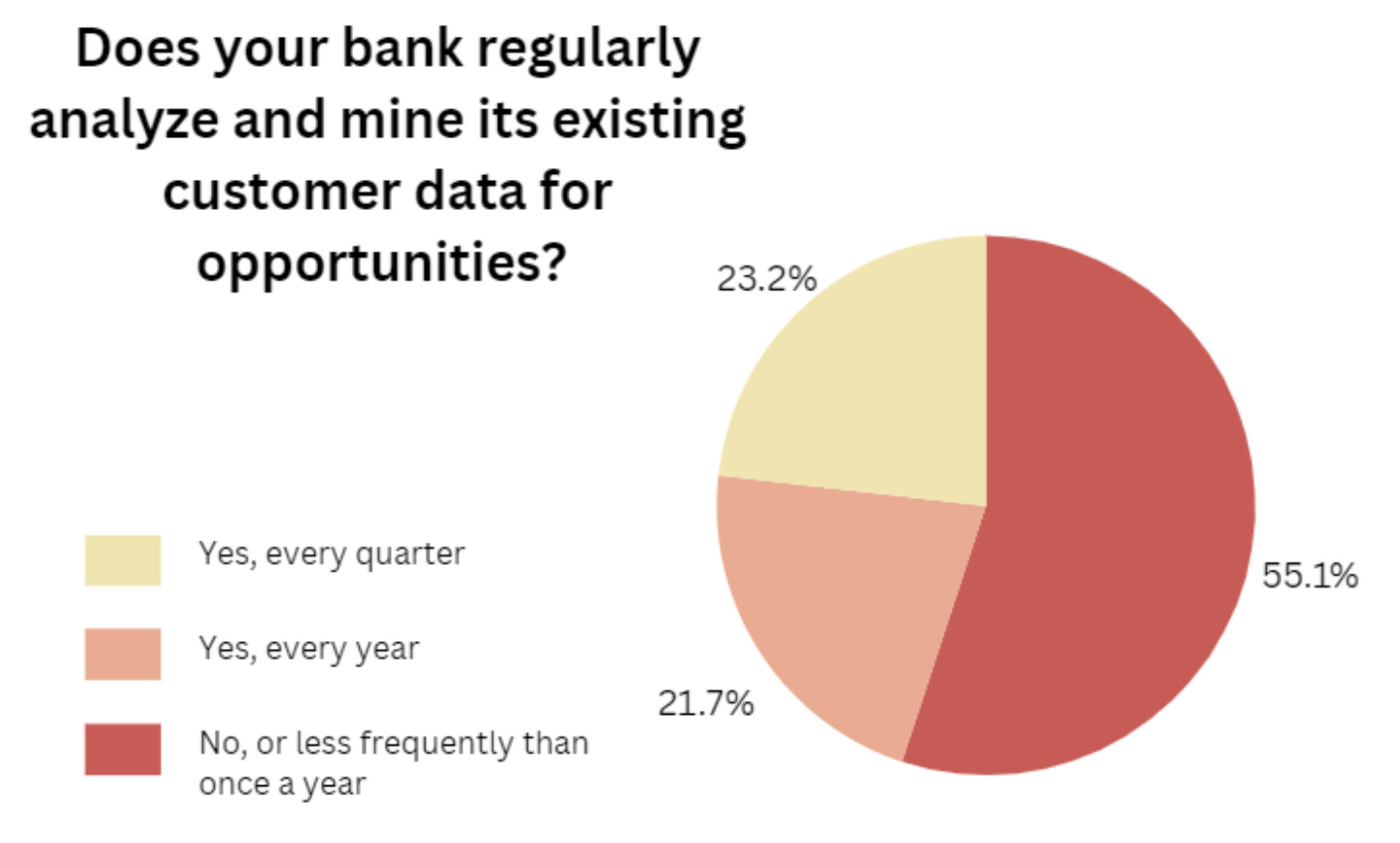

Spending on digital capabilities and technology is easy; getting customers to use revenue-generating products is where differentiation lies. Of course, this requires a robust data & analytics function. Yet, in the recent American Bankers Association survey, over half of banks were not mining those insights even annually:

To address this gap, FSIs don't necessarily need to significantly increase their spending but rather look for a different talent profile. Marketing groups dealing with customer data tend to attract more creative, people-oriented types. It is very hard to find one person who combines those skills with a strong analytics propensity, and vice versa. Hence, the answer often requires hiring two different profiles for each segment/product/channel.

With a stronger talent mix, FSIs could build differentiated models that even leading fintechs might not have yet. For example, first Chase, and now Wells Fargo, claim that their chatbots will be proactively alerting customers to their unhelpful behavior:

Finally, for many financial services and insurance products, digital features are not the primary reason for customer engagement. Similar to selling Bentleys, the brilliance of some FSI products like hedge funds is that their value proposition could be built on exclusive access. Despite disappointing performance or mediocre digital features, leading players cleverly satisfy the desire of their clients to feel exclusive through direct access to experts and their reports.

The trick for FSIs is to create an operating model (aka "culture) where spending less on digital capabilities is rewarded and doesn't preclude a much higher spend when there is a clear investment opportunity again. If executives feel comfortable asking for a 25-50% reduction or increase in any spend bucket, then eventually FSIs could even trust them to spend money without getting pre-approval. Now, that would be quite a differentiation against peers.

![budget cut #2 [dilbert] : r/comics budget cut #2 [dilbert] : r/comics](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3a4741fe-bd5f-4792-98d4-78e43a79a144_403x125.jpeg)