The Best Way for an FSI to Feel Good About Social Impact: Don’t Measure It

Also in this issue - Finita La Commedia: The End of Financial Inclusion Illusions

The Best Way for an FSI to Feel Good About Social Impact: Don’t Measure It

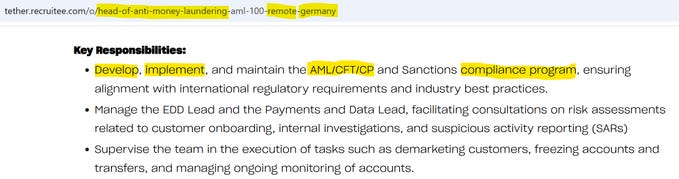

For the first decade after crypto's invention, the industry's naive hope was to disrupt fiat-based private and government payments without engaging with regulations. Yet, the Fed, Visa, and Western Union remain firmly in place, while many early crypto startups have disappeared—and some founders ended up in jail for regulatory violations. Those that survived are adapting, at least attempting to operate within the rules. Even the enigmatic Tether has recently begun searching for a Head of AML:

The more amusing aspect of crypto's origin story is that it was envisioned as revolutionary not just for its technical superiority, but for its promise to empower consumers to be their own bank. That vision has largely fallen flat, as most consumers are uninterested in becoming financial experts. Meanwhile, traditional FSIs and fintechs have significantly enhanced their value propositions since 2008. As a result, crypto adoption has been limited to a niche group using it for trading, some diversification, or as a means to bypass capital controls.

In 2017, when a Nigerian student mentioned paying 20% in fees to send a wire, the US classmate’s “wise” response wasn’t to suggest a cheaper ACH-based alternative but to launch crypto trading across 20 African countries. Bloomberg recently profiled that startup, Yellow Card, intriguingly framing its value proposition as a “workaround for currency shortages.”

The absence of positive social impact is equally apparent in the case of crypto’s government counterpart, Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs). Despite numerous pilot programs worldwide, it remains unclear what real problems CBDCs are meant to address. Christopher Waller, a Federal Reserve Board of Governors member, highlighted this persistent ambiguity in a recent speech, noting the lack of clarity even after more than three years of exploration:

“… three years ago there was an increase in public discussion about creating a new payment instrument called a central bank digital currency (CBDC). The Federal Reserve Board was compiling a report and seeking public comment on the potential benefits and risks of the idea. In a speech I gave in August 2021, I asked, what problem would a CBDC solve? In other words, what market failure or inefficiency demands this specific intervention?2 In more than three years, I have yet to hear a satisfactory answer as applied to CBDC.”

This dimension of the crypto industry is amusing because its leading players continue to portray themselves as drivers of positive social impact. The rationale is clear: governments would likely feel less hesitant to shut them down without this perception. To maintain this image, companies like Coinbase have been running ads emphasizing how their products supposedly address regular payment and money transfer needs.

Many of Coinbase’s ads feel trapped in a time warp, seemingly stuck in 1979, presenting modern crypto solutions as superior by comparison. Even 12 years after its launch and with claims of 50 million crypto users, Coinbase still hasn’t managed to feature a single real-life user genuinely relying on crypto for payments or transfers. One recent ad, for instance, claims that only crypto can help a mom send emergency funds to her son in Mexico. Does Coinbase’s marketing team not realize this has been possible for over 25 years—or do they not care to know?

Asking what market failure crypto solves is like questioning the value of ice cream or video games. Crypto is entertaining, with its own set of trade-offs, and while its disappearance might be lamented briefly, it would likely fade into obscurity over time.

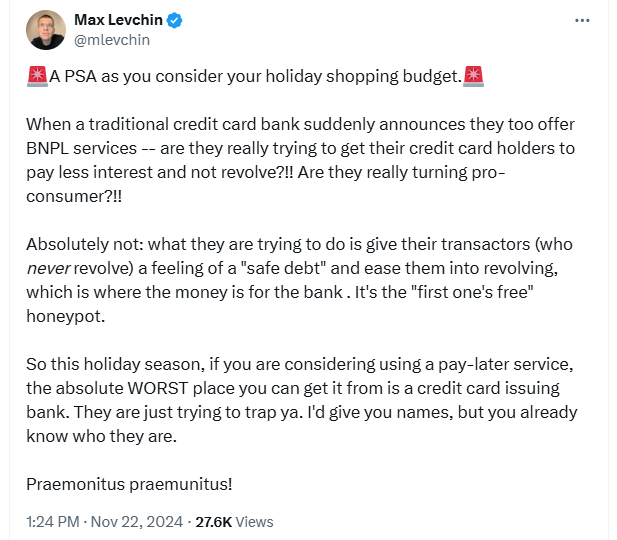

To be fair to Coinbase and its peers, some fintech companies share a similarly odd insistence on creating a positive impact. Take Affirm, a leading BNPL provider, which regularly criticizes banks for offering "usurious" credit products. Most notably, Affirm’s CEO recently likened banks to drug dealers, accusing them of positioning their own BNPL products as a gateway drug to hook consumers on more expensive credit products down the line:

I call it “Critical BNPL Theory”—criticizing banks for trapping consumers in debt while failing to prove that BNPL has a net positive impact on those struggling with debt. Despite numerous requests and having access to their customer credit data, Affirm consistently avoids sharing any meaningful insights.

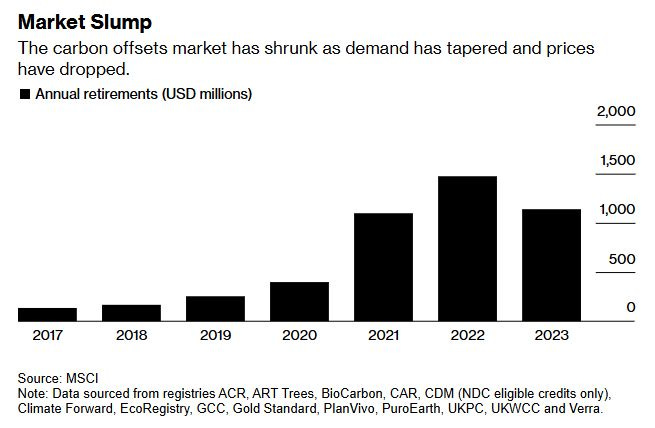

In some corners of the financial services industry, making grand social impact claims is becoming more challenging. ESG funds are under increasing scrutiny, and now carbon offsets, another staple of greenwashing, are falling out of favor. Enron’s once-brilliant invention was designed to make executives feel good about their environmental impact without ever needing to prove whether forests in distant countries were actually planted—or even existed.

Without carbon offsets, FSIs might resort to greenwashing their way to net zero with initiatives like annual tree-planting drives or rebranding themselves with words like "organic." The challenge of pretending to have a positive impact on climate is further complicated by the massive energy demands of GenAI adoption in FSIs, which has driven such a surge in data center usage that the "sustainable" outcome in some cases has been the reopening of fossil fuel power plants. Some FSIs seem to lack even the energy for pretense, choosing instead to quietly downgrade their sustainability functions altogether.

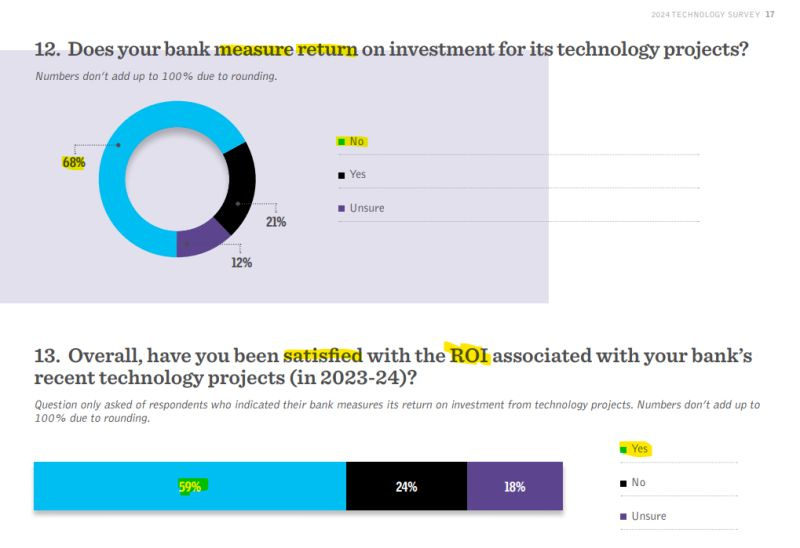

The trick for traditional FSIs is to steer clear of areas where social impact is regulated and subject to measurement scrutiny. Instead, they can take a page from some crypto and fiat fintechs, focusing on topics where nobody can demand numerical proof. With "ignorance is bliss" as a guiding principle, FSIs might approach social impact the same way they handle technology projects. In a recent survey by Bank Director, the majority of FSI executives admitted they don’t measure ROI—but that didn’t stop most of them from feeling satisfied with the outcomes.

Finita La Commedia: The End of Financial Inclusion Illusions

It’s a fascinating time to live in the US after growing up in one of those “shithole” socialist countries. My favorite part is the widespread embrace of price controls on financial and insurance products at the state and federal levels, all in helping poorer consumers with financial inclusion. Neither the history of countries like my homeland, with empty shelves and hours-long queues for basic goods, nor that FSIs have already stopped offering products in certain markets, seem to deter the growing bipartisan support for such measures.

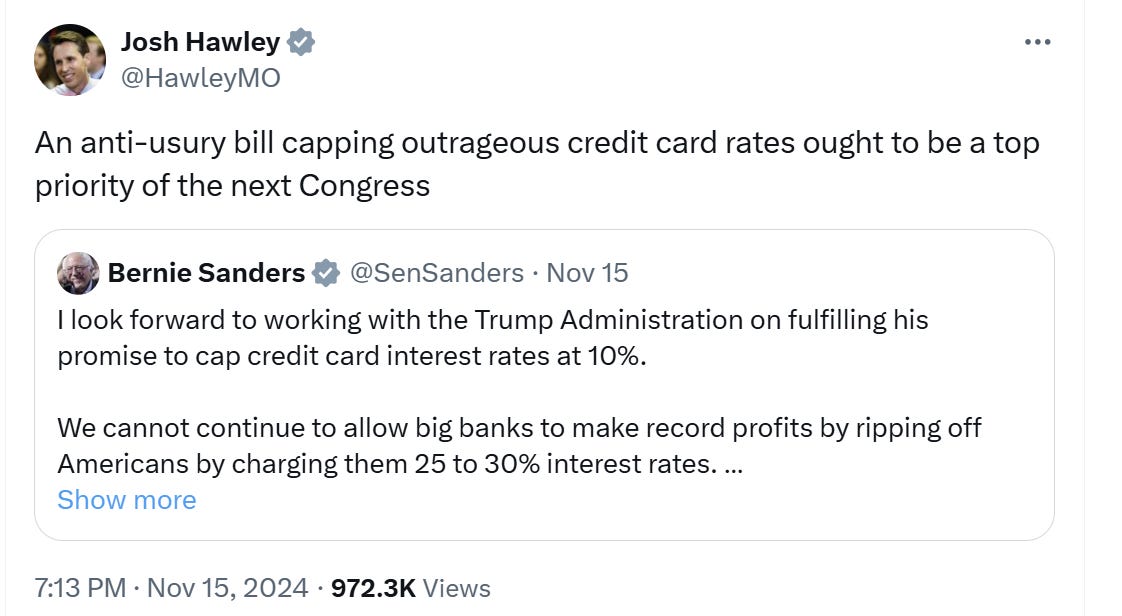

Trump’s promise to reverse the increase in auto insurance prices by half or cap credit card interest rates at 10% has recently garnered active support from leaders in both parties. They believe that limiting prices will mostly hurt opulent bankers who are seen as exploiting the poor. Well, at least for now, bankers aren’t in danger of being massacred or losing their properties, unlike the fate of Jews during Edward I's reign in England when usury was made illegal more than 800 years ago.

Besides price controls, another solution frequently proposed for financial inclusion is stablecoins. But has stablecoin usage significantly reduced the number of unbanked among the homeless in the Bay Area, or in states with the highest concentrations of unbanked populations, such as Alabama and Mississippi? Apparently, it's already transforming global finance to support financial inclusion:

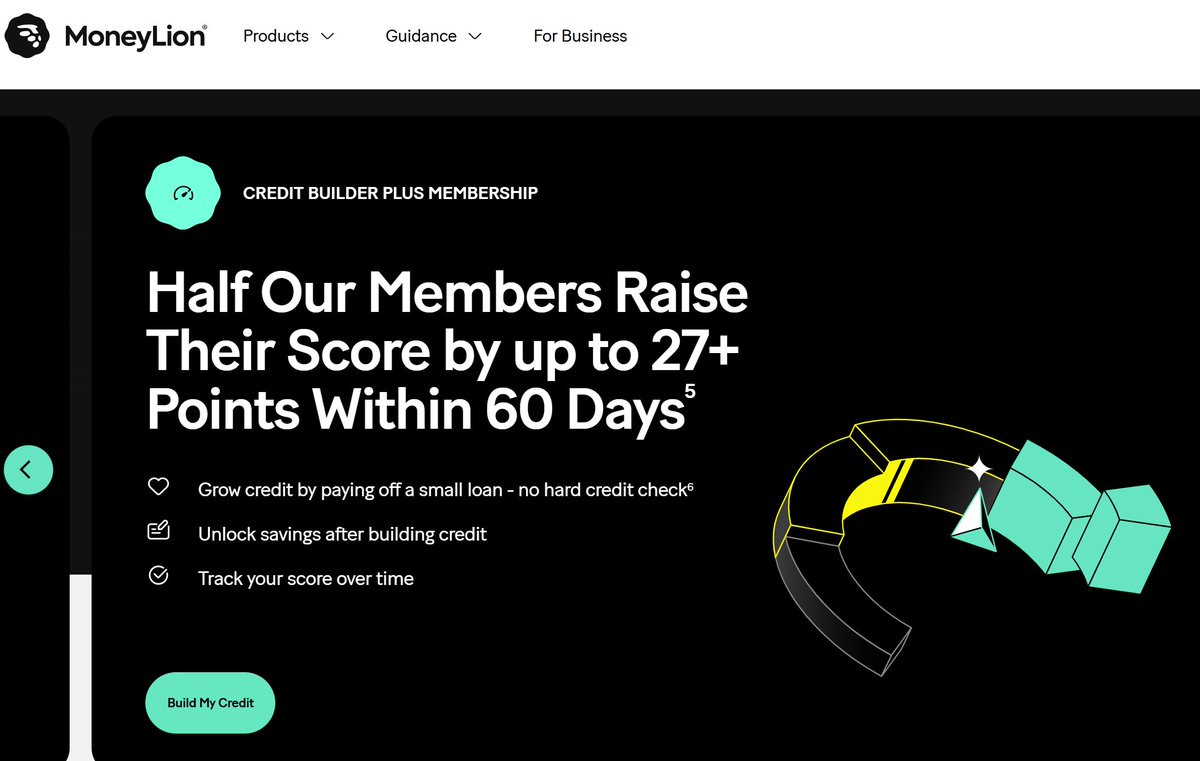

In addition to peculiar government solutions, some fintechs offer products related to financial inclusion. For example, MoneyLion offers a Credit Builder Plus membership for $20 per month, which has apparently helped boost credit scores by over 27 points for half of its users within just two months:

That sounds incredible, except those points don’t carry the same weight as those from traditional credit activities, meaning they don’t necessarily guarantee expanded financial inclusion. It’s surprising that credit bureaus even allow fintechs like MoneyLion to tout credit score boosts. After all, these fintechs often resell the bureaus’ products, which raises questions about potential incentives at play in such promotions.

However, the foundational issue with financial inclusion in developed economies isn't necessarily the irrelevant or harmful solutions, but rather the flawed premise behind why some consumers face higher prices or are excluded from FSI products altogether. Much like my conviction about the West growing up in the Soviet Union, the prevailing belief today is that this exclusion stems from unfair treatment of consumers based on sex and skin color.

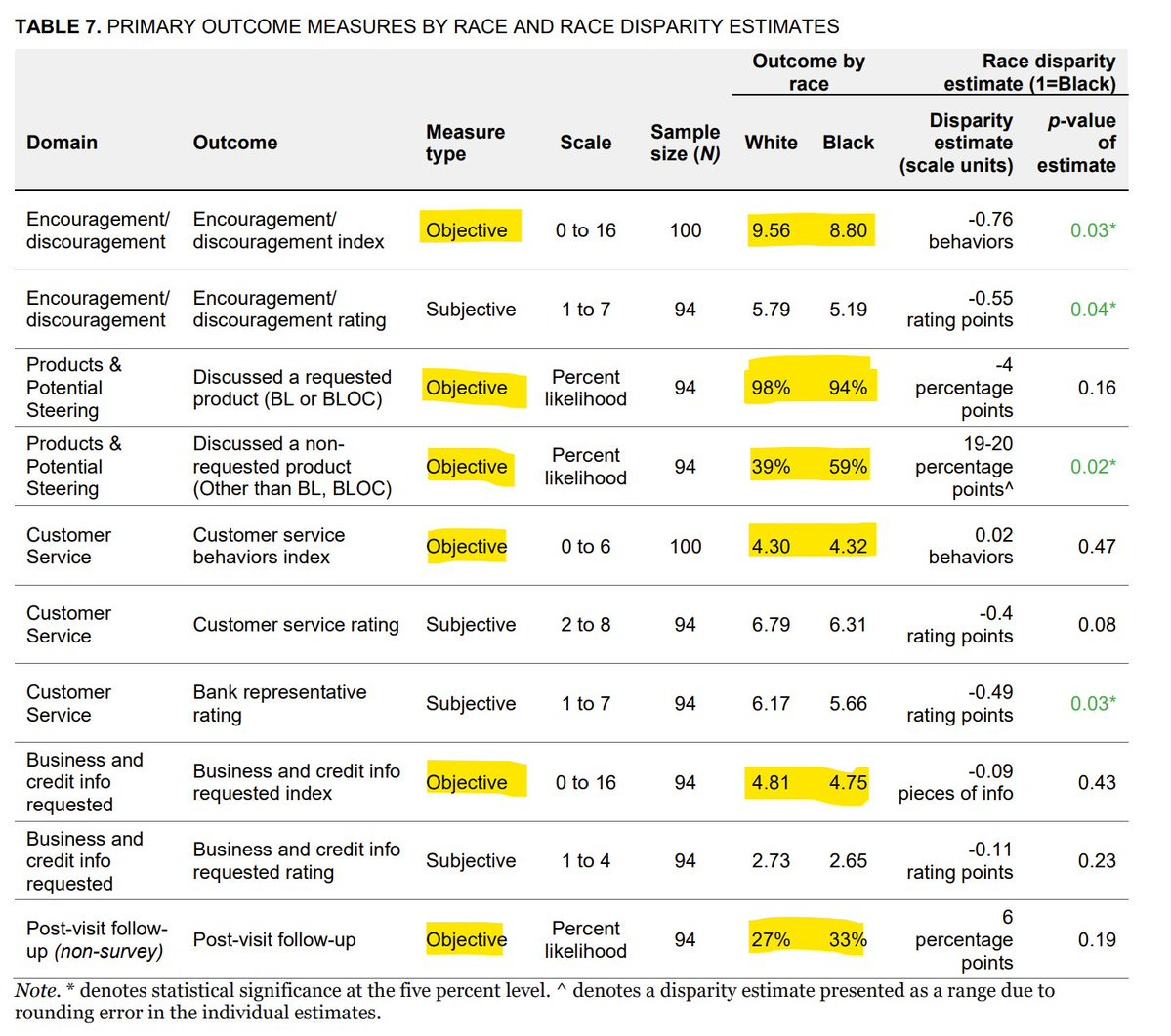

For skeptics, the CFPB recently conducted a study comparing how black and white small business owners were treated when sending actors to various banks. The conclusion appears clear and fact-driven—US banks and their bankers exhibit racial bias.

However, when looking at the actual objective results, black small business prospects received better follow-up, were asked for less information to secure a loan, and experienced better customer service. Even on the supposedly most damning dimension—being encouraged to apply—black prospects scored 8.8 out of 10. While that score may not be exceptional, it doesn’t suggest a significant barrier to financial inclusion.

Another popular focus of financial inclusion is the younger generation. A barrage of articles often portrays each new generation as a victim of financial hardship, unable to access the same products as their predecessors. In reality, however, each new generation, especially Gen Z, has been earning more, becoming smarter investors, and saving better than previous generations.

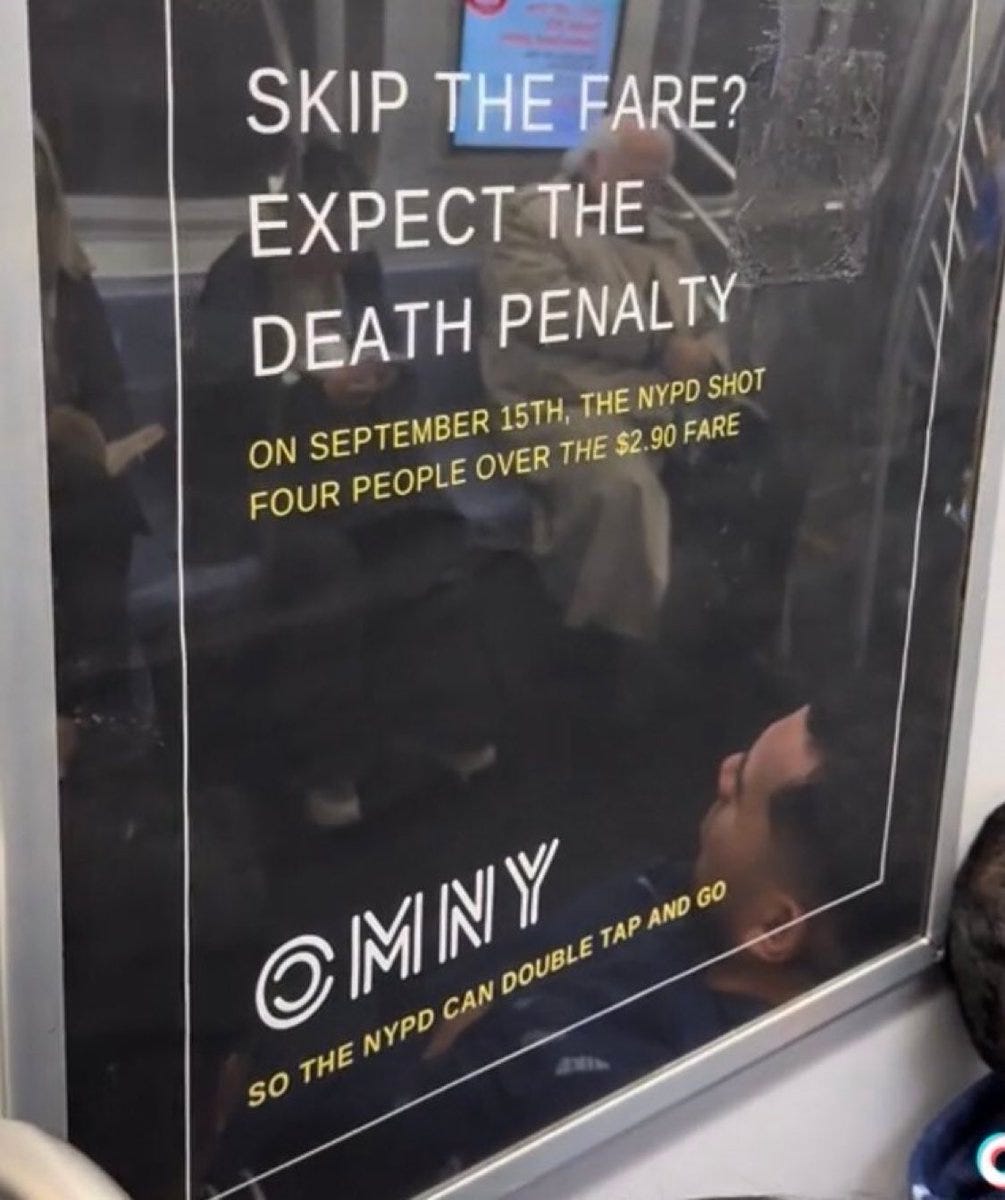

The best way to achieve financial inclusion for the remaining unbanked in the US is by encouraging their use of readily available, free financial products. A recent shooting incident in the NYC subway sparked a protest ad mocking payment requirements. While no one, including NYPD, is advocating for deadly force against turnstile jumpers, let's not pretend that they are helpless victims of financial exclusion who require additional support from the government, banks, or fintechs offering new "inclusive" solutions.