Some FSI Sectors are Only Now Reaching their ‘Barbarians at the Gate’ Moment

Also in this issue - Digital Transformation in FSIs: Simple Target State, Highly Idiosyncratic Journey

Some FSI Sectors Are Only Now Reaching Their ‘Barbarians at the Gate’ Moment

It’s clear why consumer insurtechs have been largely inconsequential, with stocks typically down around 90% from their highs. They targeted a barely profitable industry that relies heavily on historical data and already had decent UX. But why haven’t consumer fintechs triggered a significant decline in the value of bank incumbents? Despite numerous fintechs in the U.S. and U.K. reaching scale a few years ago and continuing to grow rapidly, stocks of banks like JPMorgan Chase and Barclays have only risen:

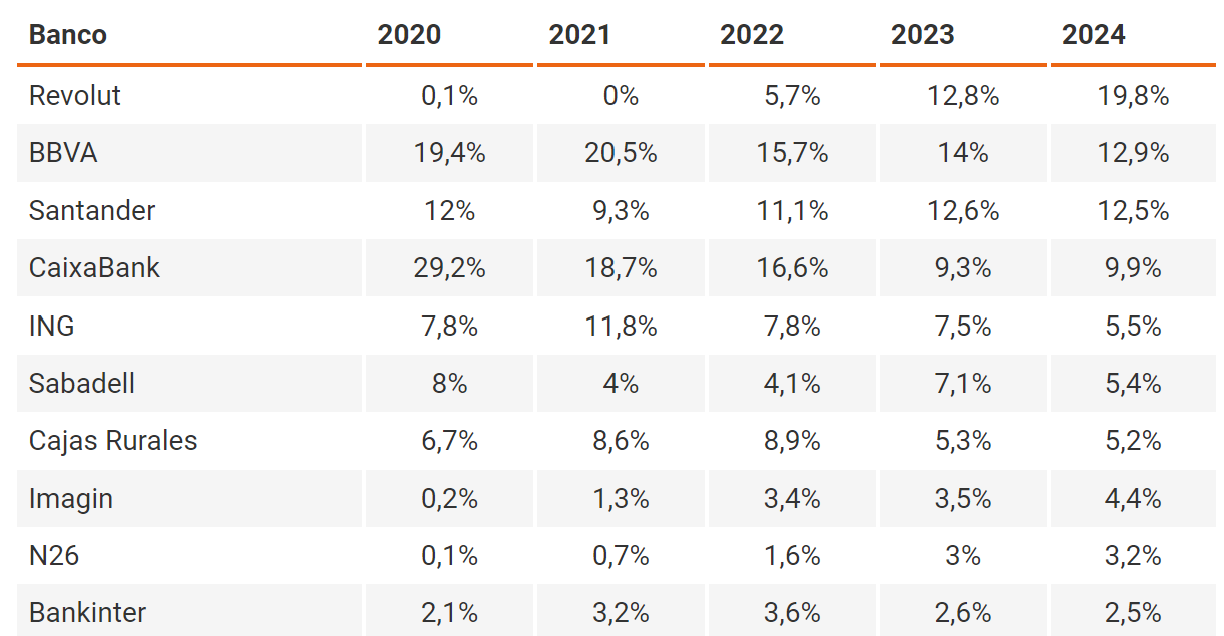

This is especially surprising given regular surveys across the U.S. and Europe showing fintechs winning the battle for new accounts. For instance, a recent Grupo Inmark survey in Spain demonstrates Revolut’s meteoric rise at the expense of some incumbents:

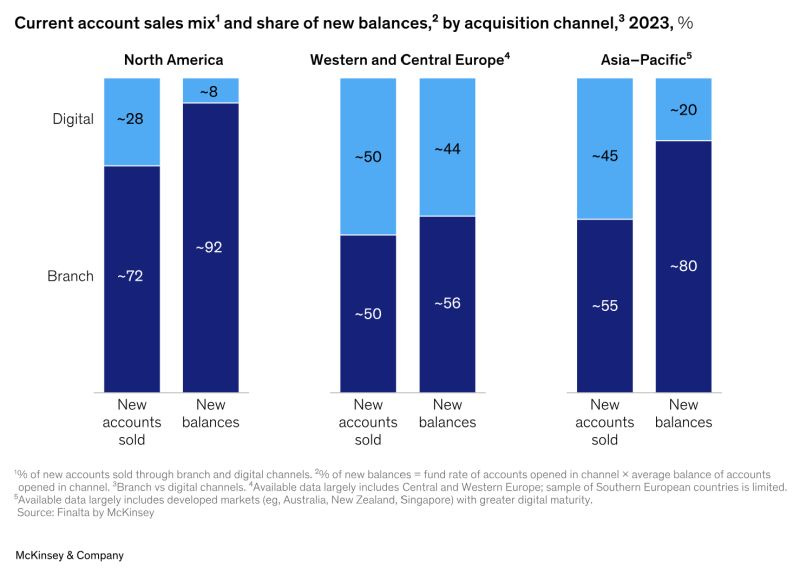

Moreover, consumer fintechs like Revolut have captured greater market share of new accounts in Europe partly because consumers there seem more comfortable with online financial services than those in North America or Asia. A recent McKinsey report highlights Europe’s digital lead not only in new retail banking accounts but, more importantly, in the balances held in those accounts:

European consumers are clearly drawn to the digital UX—an area where fintechs are supposed to shine—and Revolut has been surging in new accounts, particularly in Spain. Imagine the impact on the valuations of Spain’s two largest banks, which have seen their share of new accounts drop by a third and two-thirds in recent years. Surprisingly, the market caps of both banks have nearly doubled in the past couple of years, even as Revolut has tripled its share of new accounts to nearly 20%. What explains this apparent contradiction?

The reason lies in the types of accounts involved. Rather than replacing an incumbent with a neobank, consumers typically add an additional account for a specific niche use case. As an executive at one of Spain's top three incumbents explained to me, Revolut has established a narrow beachhead but has struggled to expand its value proposition much beyond that.

“We are seeing in Spain (and other Eurozone countries) how the average number of accounts held by customers goes from 1.2-1.3 to 2 in just 3 years. The typical use case is people that travel and want have a no-exchange fee account.”

Since the detailed results of the Grupo Inmark paid report are not publicly available, I cannot share them here. In summary, when it came to declaring primary bank relationships, less than 0.5% of survey respondents named Revolut, while the top three banks received over 60%. Regarding UX, a decade ago, there was a noticeable difference between fintechs and incumbents, but nowadays, customers of top banks often prefer their mobile apps, perhaps even more than customers of neobanks do:

Unfortunately for traditional FSIs worldwide, this doesn’t mean they can simply enjoy their current pace and assume that consumer fintechs, like consumer insurtechs, will serve more as a free R&D observatory than as potential disruptors. Leading players like Cash App and Revolut often start with simple products that don’t generate much revenue for traditional FSIs—such as money transfers, cute debit cards, and high-yield savings accounts. However, they eventually branch out into more complex but profitable risk-based products.

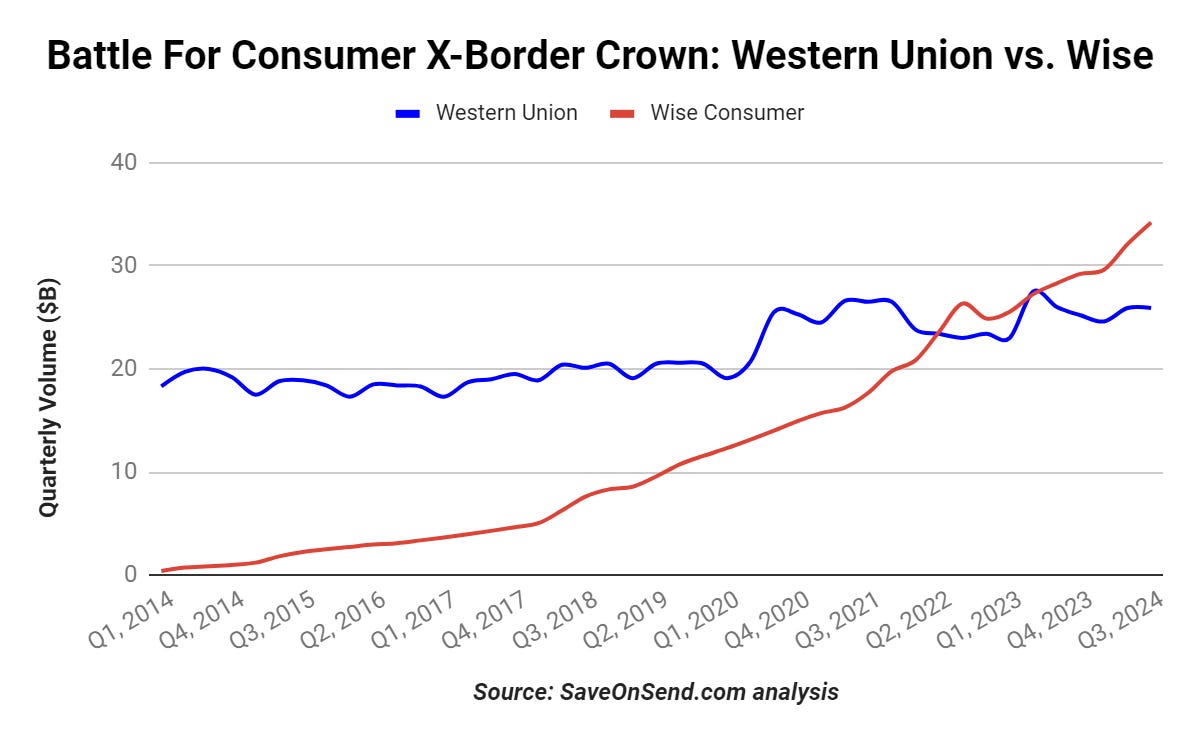

There may be a sense of complacency among traditional FSIs, as revenues won’t collapse immediately. Instead, they will stagnate, with growth trailing behind inflation. This dynamic is well illustrated by simpler products that are further along the disruption continuum. While fintechs like Wise and Remitly haven't disrupted Western Union yet, it's no coincidence that the former leader in C2C cross-border transactions hit a brick wall around four years ago—just as fintechs reached scale:

As some traditional FSIs have been experiencing stagnant revenues for years, they should treat this as a warning sign for struggling product areas. Fintechs may have conquered all the easy vassals in that space, and now they are at the gates.

Digital Transformation in FSIs: Simple Target State, Highly Idiosyncratic Journey

The beauty of digital transformation lies in its singular target state and intuitive tenets, particularly when viewed as a business transformation. It should begin with business leaders deciding to transform their groups by appointing a peer outside of IT to guide the process, helping to avoid rookie mistakes and unnecessary duplications. This individual receives a second title (e.g., Chief Digital Officer) alongside their operational role and starts optimizing for ROI and overall impact. Voilà.

Claude Wade, AIG’s Chief Digital Officer and Head of Business Operations and Claims, recently shared his approach to enabling business transformation. For their core client segment of large corporates, the biggest impact to date has been reducing price quoting from weeks to minutes by leveraging Generative AI. Claude's explanation illustrated the difference from a typical FSI, where digital transformation is often viewed primarily as technology modernization:

Rather than loud, enterprise-wide initiatives, they start small and under the radar, allowing groundbreaking results to create organic FOMO.

Instead of a tech-first mindset, they prioritize aligning the new operating model and then selecting the technology that best supports scaling it.

Rather than adopting a typical kitchen-sink GenAI mentality, there's a focused emphasis on driving double-digit growth while cutting the rest.

Such a business transformation mindset remains rare in my conversations with FSI executives. The allure of generating exciting headlines for the Board and investors pushes them to view digital transformation as a top-down driver of standardization and simplification. In this context, novel technology becomes akin to a genie that will grant them a wish that would be too tedious to accomplish through intuitive means. As a result, after decades of dominance, “McKinsey” is increasingly being replaced by “AI” as the FSI C-suite’s favorite excuse for transformation and layoffs:

The wishful thinking behind this approach is that top-level restructuring, combined with the automation of front-line staff, will create enough momentum for the middle layers to align with a more advanced operating model. This is why we continue to hear major announcements about FSI reorganizations, such as those from Citi and HSBC, which, like half a century ago, anchor their strategies on simplification as some kind of self-evident virtue:

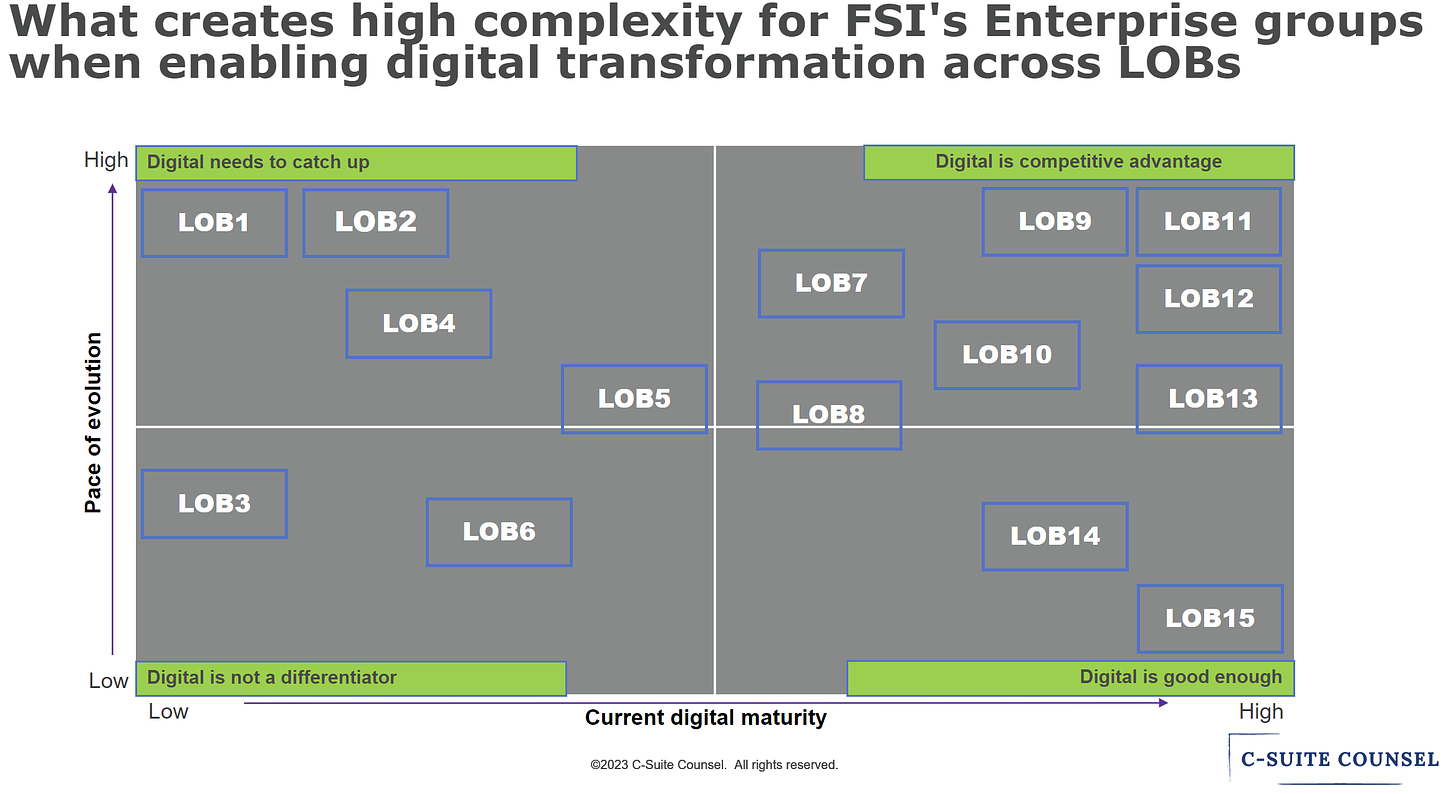

Even if we disregard the fact that HSBC's reorganization collates countries, cities, and subsets of business lines with a hemispheric overlay—setting the stage for another reorganization in a few years—digital transformation is not necessarily about simplifying the operating model. That approach may have worked somewhat in the 20th century when FSIs transitioned from treating IT as an ad-hoc nuisance to establishing robust, project-based IT structures. However, for current sophisticated use cases involving novel technologies, FSIs are highly idiosyncratic, moving at different speeds and maturity levels:

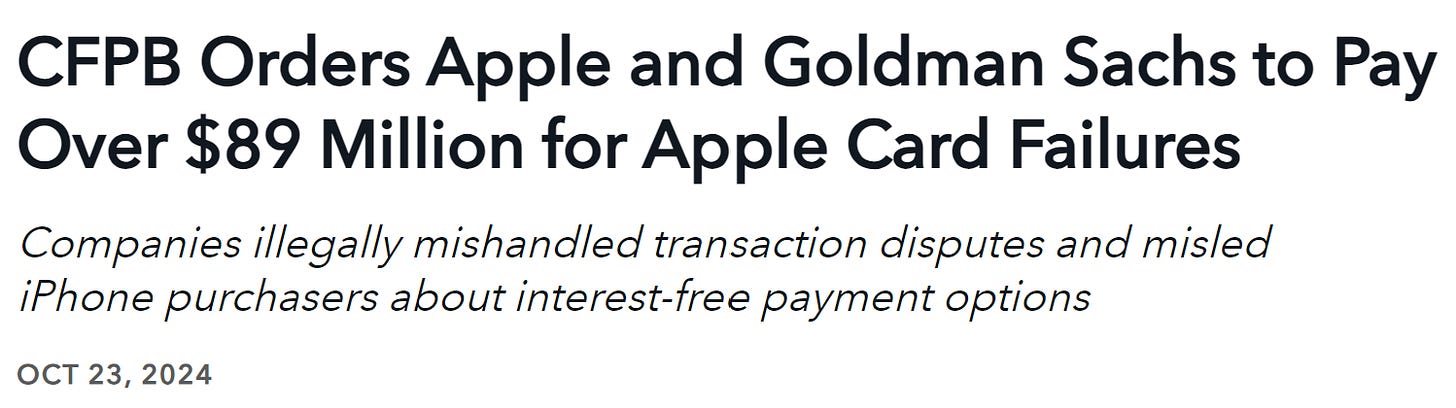

Therefore, the gradual bottom-up transformation described by AIG's Chief Digital Officer represents the most sensible approach. Top-down big-bang initiatives are designed to fail, even when orchestrated by otherwise high-performing companies. In their rush to launch a credit card, Goldman Sachs and Apple had no shortage of talent or funds. Yet, it resulted in a portfolio with an approximate 7% net charge-off rate while taking significant regulatory shortcuts:

Rather than transforming their businesses to gradually learn about new products, customer segments, and partnerships (or better yet, avoiding such excessively uncharted territory altogether), both firms appeared mostly concerned with making a splash. Indeed, it was the most successful credit launch ever, as Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon noted at the time, albeit short-lived.

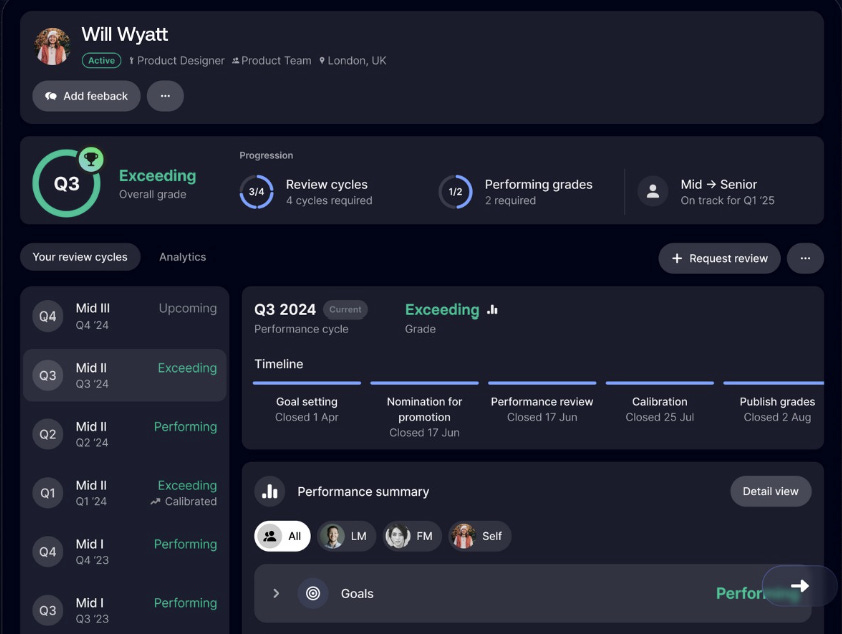

While a proven approach to transformation may seem too gradual and complicated for many FSI executives, the good news is that it will work and can be easily informed by a clear target state from leading global fintechs. Their excruciatingly detailed, number-driven playbooks for each function, even HR, feel like "rocket science" and are often unattainable for most traditional FSIs. Nevertheless, they facilitate easy alignment among executives, helping to guide incremental improvements in operating and technology models.

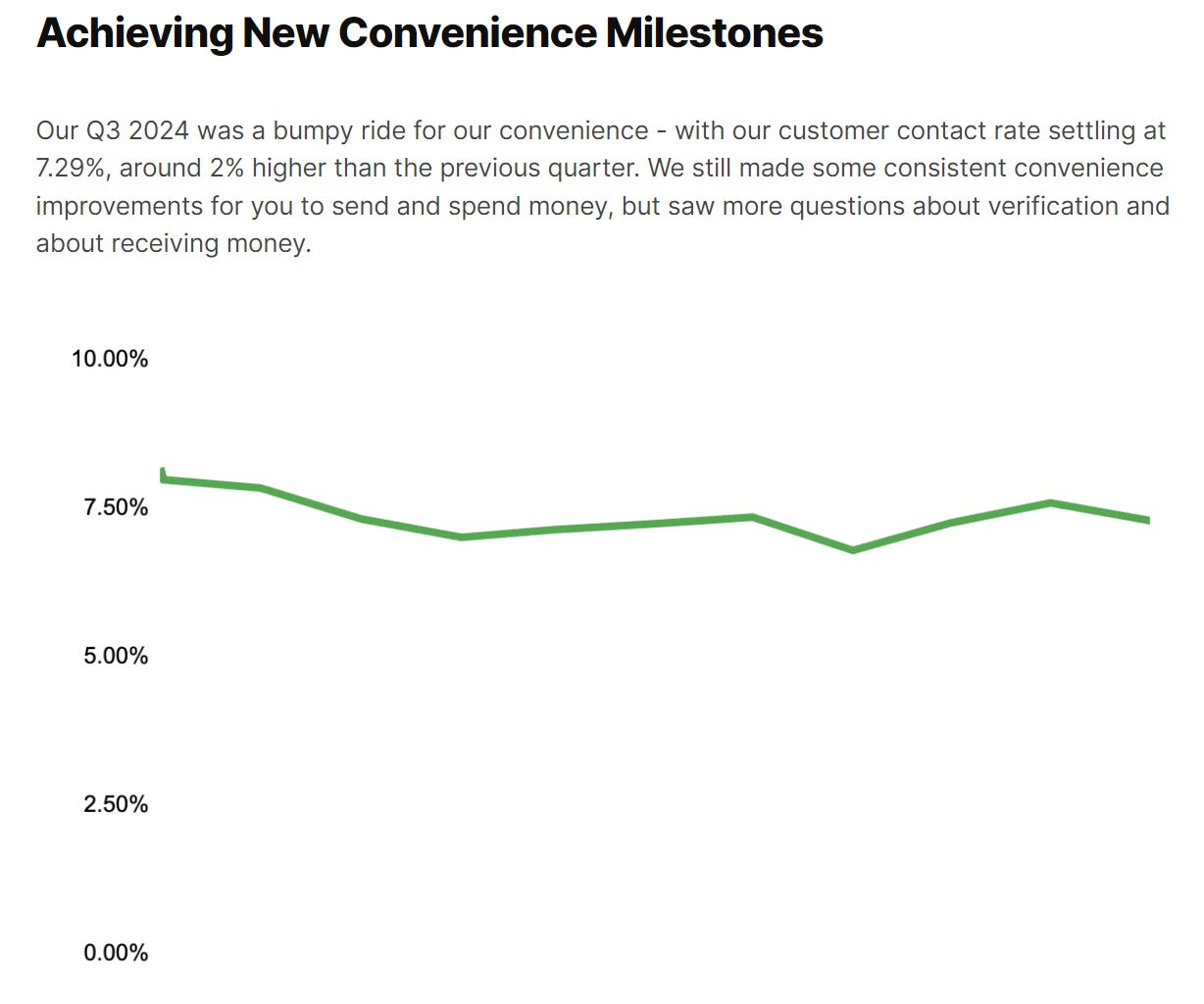

Another short-term benefit of this approach is a more thoughtful allocation of innovation efforts. For example, discussions about using GenAI to drastically cut contact center staff often miss the forest for the trees. Unlike the analog mindset, a fintech-grade operating model views the contact center as a key identifier of upstream UX flaws. As product features expand, the contact center becomes ground zero—a canary in the coal mine—in the race between inevitable UX issues and the product team’s ability to fix them.

With this understanding, your FSIs could still decide to maintain traditional North Star metrics for contact centers, focusing on efficiency and customer satisfaction. However, you could also align internally on when you would be ready to level up closer to fintechs like Wise, whether in a few years or decades. At what point will understanding why customers are reaching out become fundamentally more important to your FSI than merely resolving their issues efficiently?

Even if the CEO conducts simplification reorganizations every few years, it won’t change the target state and unique digital needs of each business line and function in the meantime. Rather than pursuing simplification for its own sake, organizations should embrace their idiosyncrasies while maintaining a clear strategic direction. It's better to have a focused strategy than to hope for miraculous momentum in the middle of the organization.