Does Your FSI Want Employees to Be Fish or Dolphins in a Digital Transformation?

Also in this issue: Two Unanswered Questions That Determine Crypto’s Usefulness for FSIs

Does Your FSI Want Employees to Be Fish or Dolphins in a Digital Transformation?

It’s been a year and a half since Jack Dorsey returned to hands-on management at Block, yet revenue continues to grow only in the mid-single digits, and the stock price remains flat. Dorsey appears to have tried nearly everything: reorganizing every part of the company, conducting multiple rounds of layoffs, shifting to at-will terminations by managers, and freezing most hiring at the 10,000+ employee fintech.

These moves—staff reductions, strategic realignment, and hiring slowdowns—wouldn’t be out of place at a traditional FSI struggling to grow. What stands out at Block is the decision to reassign 193 managers into individual contributor roles. On paper, that’s a bold move. After all, a manager’s #1 job during digital transformation is to accelerate the leveling up of their direct reports. Those who prefer to act as mentors or peers should be accountable only for themselves. But will that be enough?

Block now faces a challenge shared by many traditional FSIs and decade-plus-old fintechs: As operating models age, entropy increases to the point where empowering autonomy—the cornerstone of digital transformation—can become counterproductive. It's like asking a tightly synchronized school of fish—spooked by any movement—to go out and explore new depths.

In high-entropy environments, digital-related change is often better managed through a traditional, 20th-century PMO. That model thrives in structured, disciplined settings where individual contributors aren’t expected to overthink their roles. But when transformation initiatives are fluid and uncertain—as they usually are—a school of fish quickly becomes disoriented.

The real challenge for the CEO of a traditional FSI or fintech like Block is how to help fish become dolphins. Unlike fish, dolphin pods show dynamic group behavior. They learn socially, communicate constantly, and can adapt fluidly—breaking off for solo tasks and rejoining later, even forming temporary alliances. They don’t need micromanagement; they need intelligent coordination.

Your first instinct might be to bring in consultants and sophisticated agile frameworks to enable that behavior. But in practice, these enablers often overwhelm rather than uplift. New technologies like GenAI don’t compensate for a flawed operating model—they amplify its existing strengths and weaknesses.

The only way to truly accelerate transformation in employee effectiveness is for the CEO to lead from the front—personally leveling up their direct reports and helping those leaders do the same for their teams. This process often feels like dragging a stubborn donkey up a hill by its ears, praying it will appreciate the view once you reach the top.

Most CEOs want no part of that grind. It’s far more enjoyable to swap generic war stories, buy companies, or rally for the underserved at industry conferences. Former PayPal CEO Dan Schulman embodied this approach, focusing internal meetings on lofty values while letting a pile of random acquisitions gather dust. His successor doesn’t appear to be much more hands-on. One PayPal insider said, “The new CEO is so unimpressive that most executives are starting to miss Dan Schulman.”

In his recent shareholder letter, even JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon seems too tired to micromanage the leveling up of his reports and their reports. While he may believe he could do their jobs better in his sleep, how does he plan to help his top 400 leaders operate more effectively? At a recent internal senior leadership conference, Dimon led a kind of “master class” that included crowdsourcing efficiency ideas and promising one-on-one follow-ups:

“I’m going to ask each and every one of you, personally – and I'm going to track it – to send me an email. We’re going to have a little team to take these issues you raise and follow up, and this will be permanent. I kind of like bureaucracy busting to get things done. It could be stupid things you’ve observed, any ideas, almost anything. We're not trying to limit you to any specific category.

You’ve got something to say? You want to add something? You want to check out something? You think something doesn't make sense? Please bring it up. Too many people stay in their lane. I'm going to follow up personally with each and every one of you in this room.”

For decades, ideation programs with prizes have been a staple across FSIs worldwide—but they were designed for front-line employees, not senior executives. If any of those leaders isn’t already rapidly growing the profit of their revenue-generating products or scaling their support function effectively, they should be micromanaged until they succeed—or be replaced. Asking underperforming executives to generate ideas may do more harm than good in the long run.

This same disregard for the true accelerators of digital transformation was evident in a recent CIO Online article, which outlined 12 ways to expedite transformation. Notably absent were the three most impactful actions:

Define business initiatives that are only possible by transforming IT’s operating model.

Align CIOs and business leaders on what that transformative model looks like and dedicate time in the trenches to practicing it.

Select talent across business and IT who already operate at that level—or can get there quickly with focused micromanagement.

Now, contrast that with the refreshing honesty of Tokio Marine CIO Robert Pick in a recent interview. He described the real struggle of improving decision-making through so-called agile, acknowledging that transformation is a deeply personal, decade-long journey of missteps and confusion. At its core, it’s about changing how people work—starting at the C-suite and reaching all the way down.

If your FSI truly wants to accelerate digital transformation, it must begin by accepting one hard truth: everyone—from executives to analysts—will need to evolve from fish to dolphins. The real question is, do they want that?

Two Unanswered Questions That Determine Crypto’s Usefulness for FSIs

Some friends invited me to join their crypto startup over a decade ago. I was intrigued, but their predictions—that Visa and the Fed would vanish within a few years—sounded utterly insane. So, instead, I launched a cross-border transfers blog while they went on to build a crypto conglomerate and become gazillionaires. To this day, the defining feature of the crypto movement remains unchanged: brilliant, very successful people saying completely insane things.

Having extreme beliefs hasn’t stopped Jack Dorsey’s fintech, Block, from generating $10 billion in Bitcoin revenue in 2024. The company is so committed to crypto that its expanding team in Canada is now building proprietary mining rigs and chips.

Trump’s exuberance around crypto has pushed even previously cautious FSIs to jump into the space with renewed intensity. Fidelity, for example, has opened dozens of roles with “crypto” in the job description. A recent EY survey of institutional investors revealed the widespread adoption of digital assets and expectations for increased holdings in the years ahead.

So, how much of this seemingly rapid adoption is simply due to the “numbers go up” phenomenon—speculation coupled with gray KYC use cases? One of the most common defenses of crypto’s value outside of trading and illicit activities is its role in diversification. However, whenever there’s volatility, including the recent turmoil caused by Trump’s tariffs, the correlation with the US stock market remains around 90%.

The main PR focus of top crypto players is to persuade regulators and politicians that they’re primarily helping underserved populations with payments and transfer needs. This creates a hilarious dichotomy where crypto firms go to great lengths to hire actors for fake use cases while concealing their real trading customers—the ones who are actually generating the profits. A recent Coinbase ad, for example, features an actor playing a rural track salesman who’s only familiar with wire transfers and cash methods for receiving money into his bank account.

Circle’s recent IPO filing offers no indication that it’s addressing any actual pain points in payments or transfers. Instead, it reads like a ChatGPT-generated jumble of incongruent clichés that neither clarify the specific problems Circle aims to solve nor provide transparency on how much money it makes from doing so:

"Trillions of dollars in payments and cross-border remittances occur annually, often at high costs due to the complex (often multi-party) legacy rails on which they flow."

"... and with MoneyGram to support the use of USDC for global remittances on the Stellar blockchain, among others. These partnerships are still in early stages, but we expect that they will contribute meaningfully to our operating and financial performance over time."

How does Circle make money with no meaningful revenue from payments and transfer solutions? It mints coins, pays Coinbase—its equity holder—to exchange them for fiat, invests the proceeds into US Treasuries, and then splits the revenues about 50/50. Anyone can print funny money, but the real hustle is finding someone to move it for real cash. For example, I’d gladly pay Coinbase 90% off the top to push USDY (aka “Yakov’s Coin”).

And who can blame the Coinbases and Circles of the crypto world for their willful ignorance? Fiat-based payments and transfers have been improving so rapidly that it’s hard to identify remaining pain points or how to solve them. Why would leadership teams travel to El Salvador or Sub-Saharan Africa to understand why crypto isn’t taking off when they can make easy money in the comforts of the West?

Therefore, despite countless blockchain innovations since Satoshi's paper in 2008, no crypto operators or experts have answered two foundational questions about applicability for payments and transfers. They don’t know the answer to the first one and don’t want to know the answer to the second:

What can crypto/stablecoins do that fiat-based technology can’t replicate?

What are the demographics of repeat users and their core use cases?

The answer to the second question might reveal that the only material and sustainable use cases for payments and transfers are all quite risky. The clever coin issuer and distributor would distance itself from the ultimate end users through multiple intermediaries to avoid any direct connection to how they get paid for committing crimes, laundering money, or evading capital controls.

However, you might have seen reports, like those from Chainalysis, that scientifically show that illicit activity represents a tiny fraction of the overall crypto transaction volume. Pay attention to the fine print: "totals exclude revenue from non-crypto-native crime, such as traditional drug trafficking and other crimes in which crypto may be used as a means of payment or laundering."

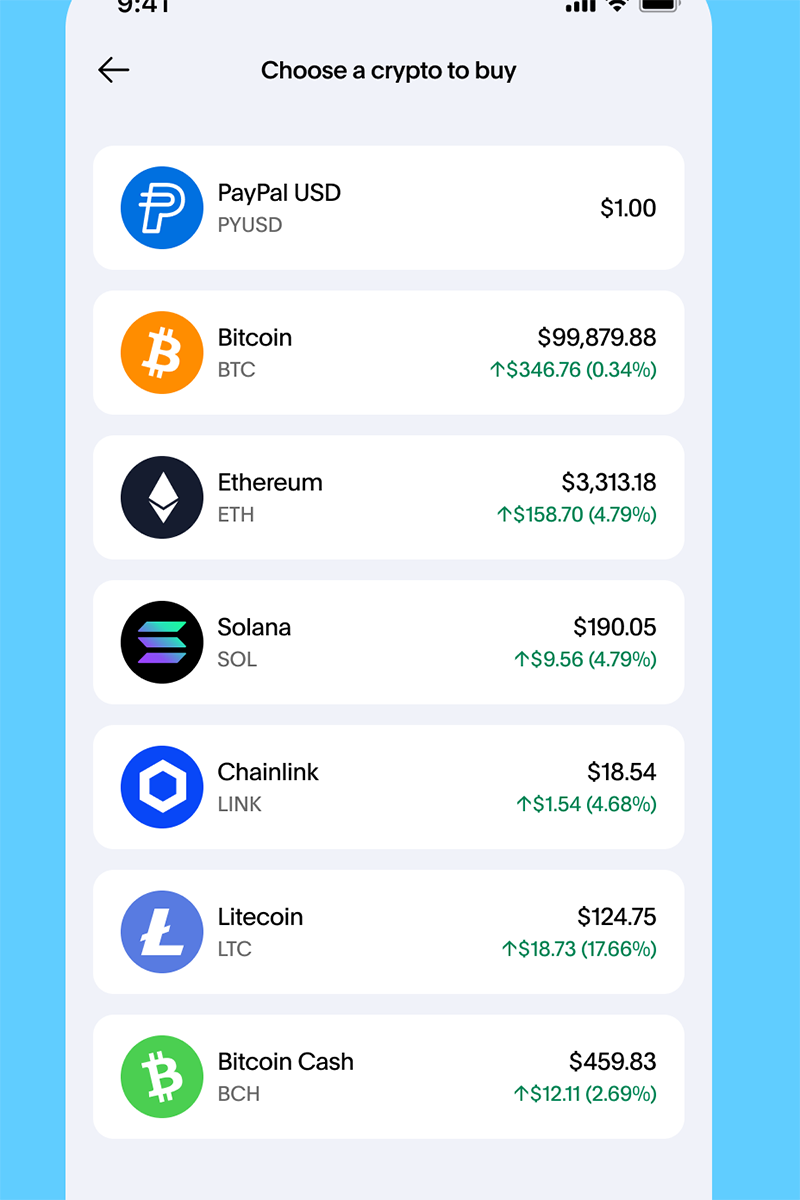

For legitimate payments and transfers, crypto players will continue a decade-long daily prayer that some fantastic calamity or miraculous regulation will finally drive mass adoption. However, it’s clear which use case is making money. In 2023, PayPal launched its stablecoin (PYUSD), supposedly to improve cross-border payments and transfers, and sold half a billion of those coins. But where is PayPal focusing to make money regularly? Of course, in trading—by adding more and more coins to PayPal and Venmo wallets.