GenAI’s Value for FSIs Hinges on Evolving Operating Models

Also in this issue: Do FSIs’ Data Products Monetize Customer Behavior or Help Improve It?

GenAI’s Value for FSIs Hinges on Evolving Operating Models

As FSIs work to master the five digital pillars of the 21st century — Agile, AI, API, Cloud, and DevOps — it’s tempting to let the technology model race ahead of operating model evolution. I still hear executives compare their tech initiatives to Uber or WhatsApp, asking why financial services and insurance technology can’t be just as seamless and valuable without requiring customers or employees to change their routines.

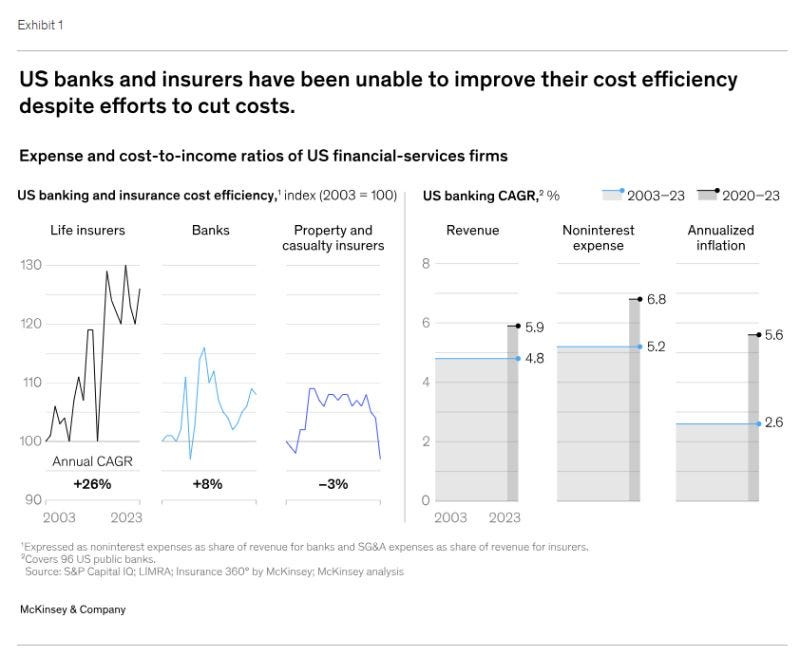

The reality is, these digital pillars act as accelerators, not substitutes, for a more effective operating model. Yet many FSIs resist transforming the business outside of IT, and the financial results reflect it. According to recent McKinsey analysis, U.S. banks and insurers made no meaningful gains in cost efficiency between 2003 and 2023. While declining NIM explains part of the pressure in some years, the bigger issue has been that expenses have consistently outpaced revenue.

What’s the takeaway for FSIs that failed to improve cost efficiency over the past two decades, despite heavy investment in Cloud, APIs, ML, and DevOps? Evidently, it’s to go all-in on GenAI, publicly declare a massive value creation opportunity, and hope for the best. As a divisional C-suite at a top-15 US bank recently shared: “Our CEO publicly claimed, for some reason, that GenAI had already created significant efficiencies. Now he’s asking every division to find those savings, and everyone’s scrambling, with nothing so far.”

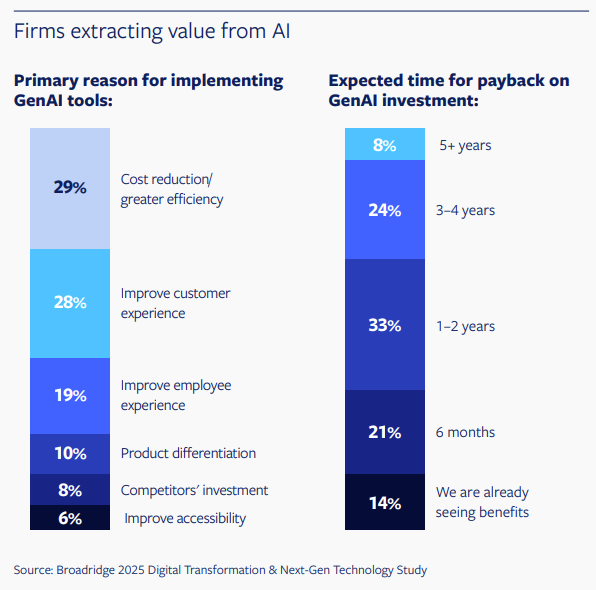

The belief that GenAI can deliver quick, material payback without significant operating model changes is encouraged by today’s budget bonanza. If even CFOs aren’t asking tough questions, why would Ops, IT, and Data leaders risk their standing by admitting the benefits are negligible or still unclear? In a recent Broadridge survey of money management executives, only a third were candid about the fact that payback on GenAI investments could take three years or longer.

I was recently excited to join a bank’s webinar on the ROI of AI. In an ironic twist, they couldn’t get the audio working, so I gave up — but received a transcript afterward. Like many large FSIs, the session focused on measurement frameworks and governance. What remained missing was any evidence of ROI capture that meaningfully contributes to overall profits. Instead, success was often defined by how broadly a GenAI capability had been scaled, not by the monetary value it delivered.

Many fintechs are also struggling to demonstrate real GenAI-driven value. The loudest hype has come from Klarna over the past two years, with no signs of slowing: “Our AI-first strategy is driving exceptional returns, we’re outpacing competitors, our merchant network is scaling rapidly, and our next-gen products are reshaping money management for millions.” But what are those “exceptional returns”? Last quarter, Klarna’s revenue growth slowed to 15%, the weakest among peers, while its pretax loss doubled.

The flaw in prioritizing GenAI technology over operating model changes is most apparent in so-called “AI-native” fintechs and insurtechs, which have remained 70–90% below their stock price highs. Despite the branding, they haven’t meaningfully transformed how they run their businesses compared to top incumbent FSIs. The real unlock will come when GenAI, not human executives, acts as the primary operator, with leaders refining AI-generated decisions and employees executing them in real time. No fintech is close to that yet.

Can you guess which part of the economy has definitely captured GenAI value? FSI vendors, of course. Accenture’s GenAI bookings have climbed from $0.6 billion a year ago to $1.4 billion per quarter. Salesforce just spent $8 billion to bolster its AI Agents platform. You might assume, with all that AI transforming sales, Salesforce would barely need human sellers anymore — yet 60% of its open roles are in Sales. While vendors continue to monetize FSIs’ search for “silver bullets,” your organization can differentiate itself by focusing on a few high-impact GenAI use cases and evolving its operating model around them.

Do FSIs’ Data Products Monetize Customer Behavior or Help Improve It?

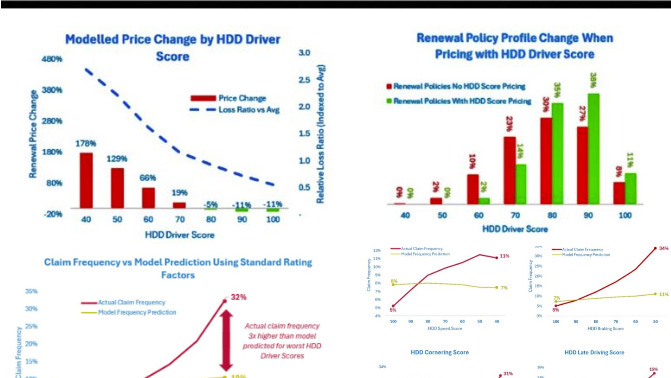

Data products have been a key source of value for FSIs, helping them avoid retaining undesirable customers for too long. The more data an FSI has on its users, the better analytics can identify risky behavior and discourage those customers through higher pricing. For example, telematics-based products enable auto insurers to reward careful drivers with discounts, while others face higher prices and are pushed to switch to competitors without such data products.

While motivated clients benefit from data products through free tools and discounts, what about customers with poor behavior patterns? In a recent interview with Semafor, John Hancock CEO Brooks Tingle points to health tools from Vitality as proof of improving customer wellbeing and reducing life insurance claims: “Two-thirds of his customers now use Vitality, of whom almost 80% report that their health is similar or has improved since joining.”

Yet after a decade offering the product, Tingle provides no further data. That quote alone doesn’t prove nudging works for John Hancock’s life insurance customers. If the goal is to present a real case, why not show the health baseline and outcomes for the one-third who didn’t enroll with Vitality, the 20% whose health declined despite enrolling, and which part of the 80% actually improved?

Traditional FSIs’ claims of “doing well by doing good” with data products paint an overly optimistic picture of their operating model. Most lack the data capabilities to micro-target customers with the right incentives. Instead, data is applied top-down through broad programs that remain unchanged for decades. That’s why bank customers still receive irrelevant marketing. Even if FSIs invested trillions to achieve full AGI, marketing will likely remain one-size-fits-all, ignoring individual usage and profiles.

Without micro-targeting, nudging with data products is even more likely to fail. Nudging—small incentives with clever positioning—works well to encourage self-selection among consumers and businesses already inclined to behave properly. For example, occasional overspending or brief phone use while driving may stop if an FSI offers a minor incentive or warning. But for habitual poor behavior, the impact is limited: a recent study attempting to reduce overall phone use while driving showed no material results.

“Together, the results suggest that incentivizing perfect streaks may have been effective among those who already had low handheld phone use but ineffective for heavy users who account for most handheld phone use. Incentivizing attainable goals tailored to each driver may be a more effective approach.”

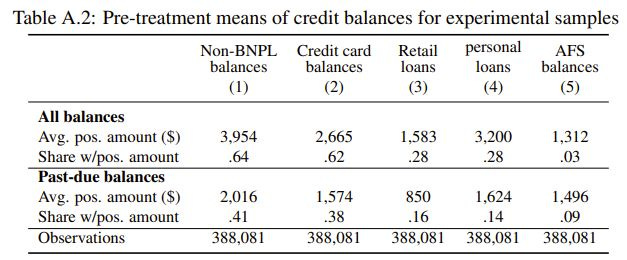

This challenge is also why traditional FSIs should view fintech claims of improving customer behavior with a high degree of skepticism. For example, BNPL leader Affirm regularly claims its product helps users stop relying on expensive credit cards, improving their financial health. Yet, it never shares detailed data on changes in credit scores or overall debt levels across its customers. In fact, no such study has been conducted. For example, the CFPB recently published research on BNPL, which included many prior debt holders; however, it strangely did not provide a separate analysis for that group.

The Fed recently published a survey of U.S. household well-being, which found that late payments among BNPL users increased by 60% over a three-year period. Block recently reported that it lends to minority groups at higher rates than national averages among small businesses and consumers. Proving positive impact would be simple: share lending volume for high-risk minority customers, then disclose how those loans performed and how borrowers’ FICO scores changed. Some likely became delinquent and worsened their credit, but hopefully, most improved their situation. We don’t know, because this information is never disclosed.

The overall benefit of fintechs for struggling consumers is also questionable. The same Fed survey showed the unbanked rate among young, low-income minorities remains unchanged from a decade ago, despite the massive growth of U.S. consumer fintechs.

Nudging remains surprisingly overhyped because of a common misunderstanding of behavioral economics. Knowing that some customers and employees act irrationally doesn’t mean small tricks, rather than substantial incentives, will change their suboptimal behavior. Smart FSIs and fintechs understand this, and instead of trying to fix bad behavior, they amplify it.

For example, many U.S. males enjoy day trading. Research shows that individual investors spend an average of just six minutes researching before making a trade. Instead of encouraging them to invest in index funds or spend more time researching, fintechs like Robinhood gamify the experience to boost excitement and profits.

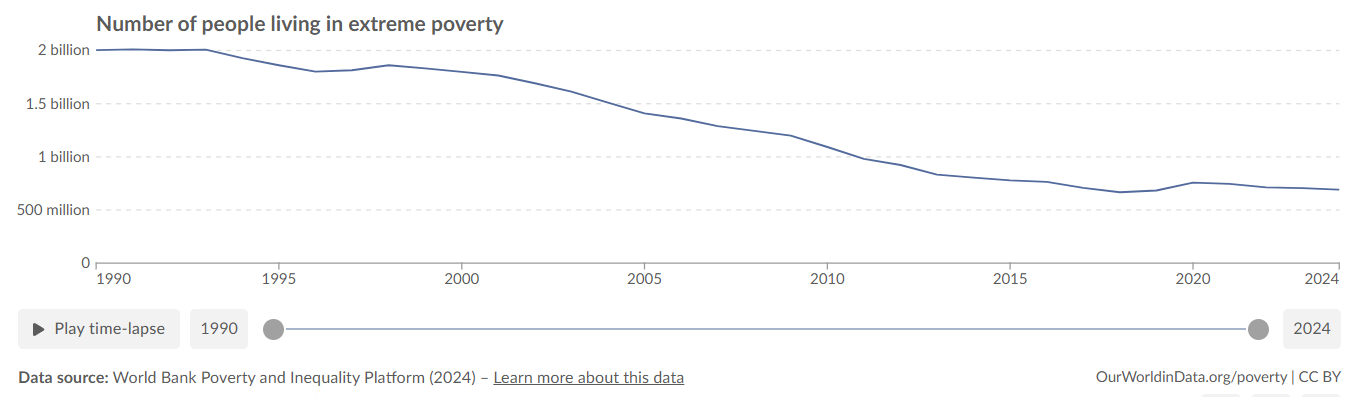

Suppose your traditional FSI isn’t willing to be overly mercurial. Instead, use data products to identify and retain your best clients while filtering out the rest. And when someone proposes a data product to improve customer behavior, demand proof that a leading fintech has succeeded at scale with that use case. Interestingly, while traditional FSIs dominated, extreme poverty rates steadily declined—but as fiat and crypto fintechs scaled around 2017, that decline plateaued.