How Are Prices Set for Financial and Insurance Products vs. What the Government Believes?

Also in this issue: Balancing Digital Transformation Maturity and Strategic Ambition

How Are Prices Set for Financial and Insurance Products vs. What the Government Believes?

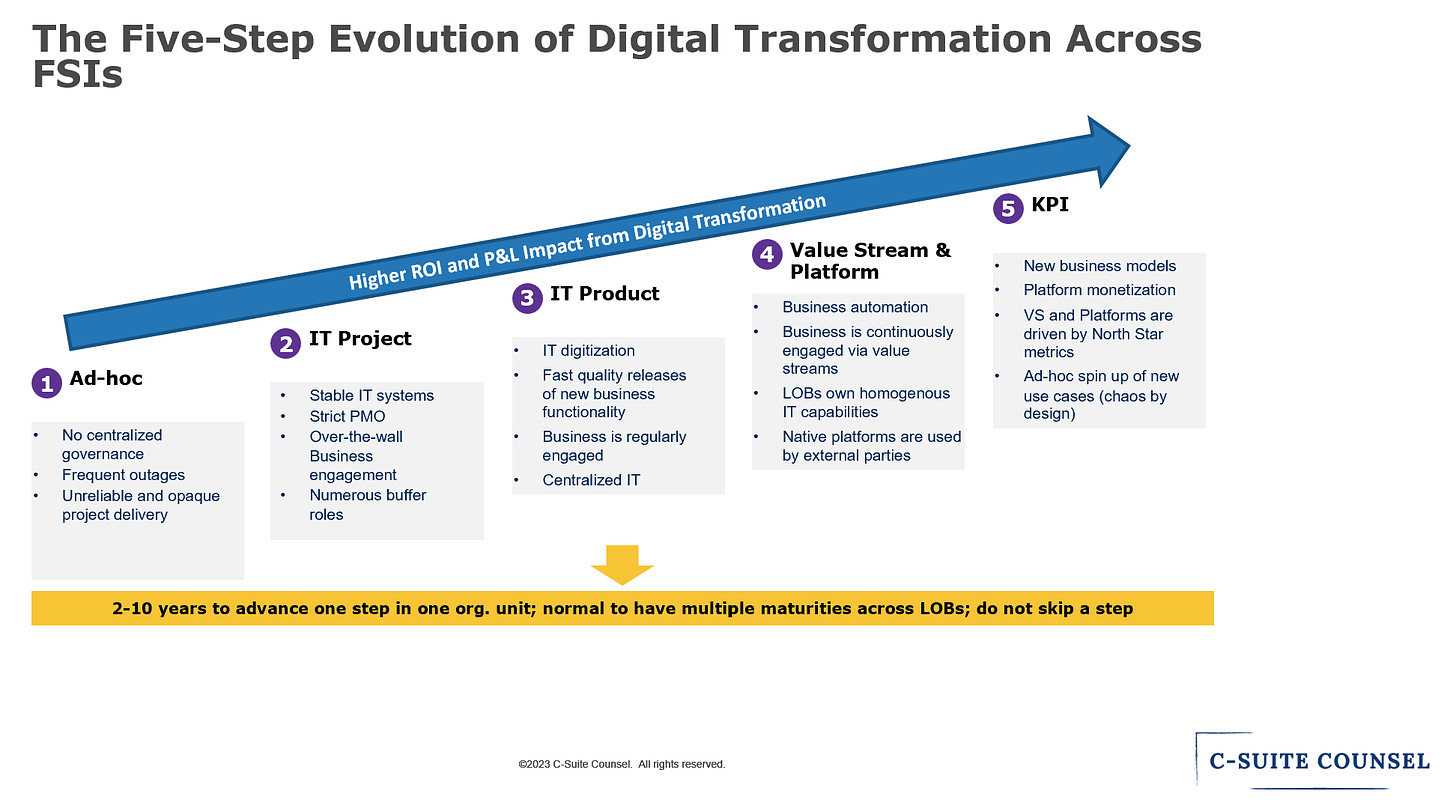

Digital transformation focuses on speeding up how businesses capture value by using digital capabilities. By enhancing the flexibility of their operating models and building in-house applications for essential processes, leading fintechs and traditional FSIs themselves apart in ways that less advanced competitors struggle to match. Over time, these digital leaders can drive laggards out of the market, either by introducing innovative business models or by providing traditional products at significantly lower prices.

Pricing complexities

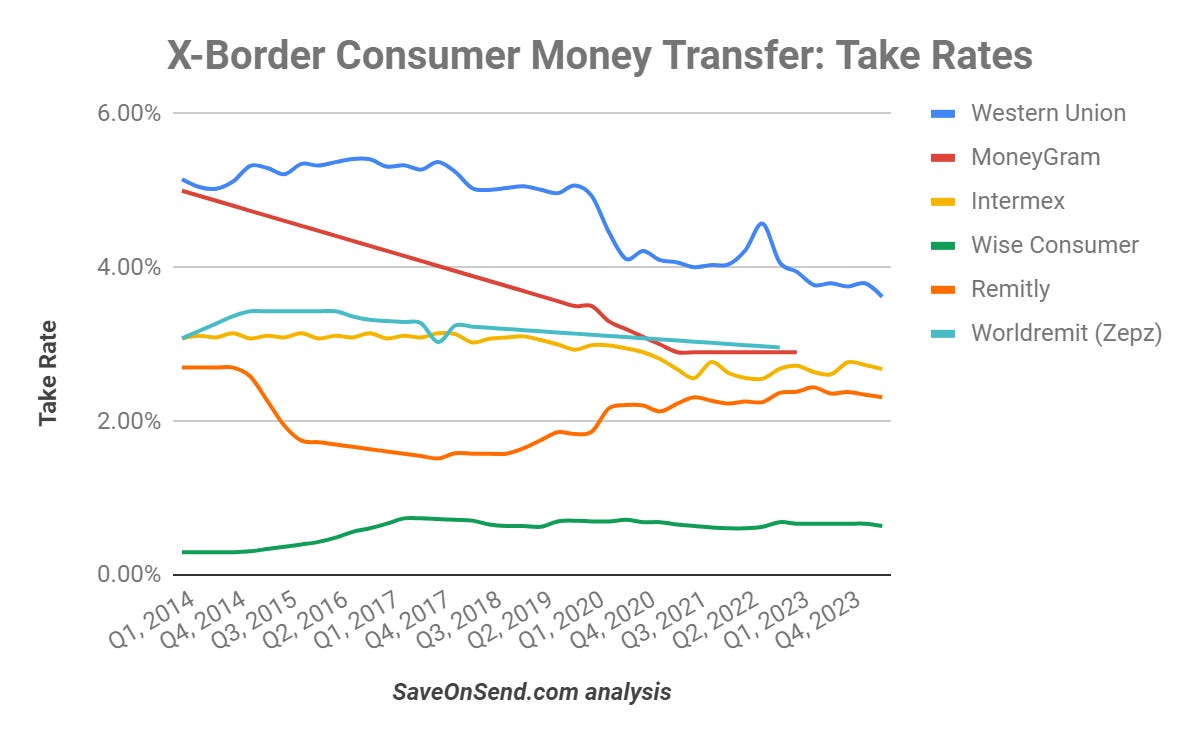

One wrinkle to price-based disruption is branding power. JPMorgan Chase, for example, offers lower interest rates on deposits than regional banks and significantly less than neobanks. Western Union charges higher fees and offers worse FX rates for international transfers compared to both traditional competitors and fintechs. The stronger the brand, the greater the price advantage needed to poach its customers.

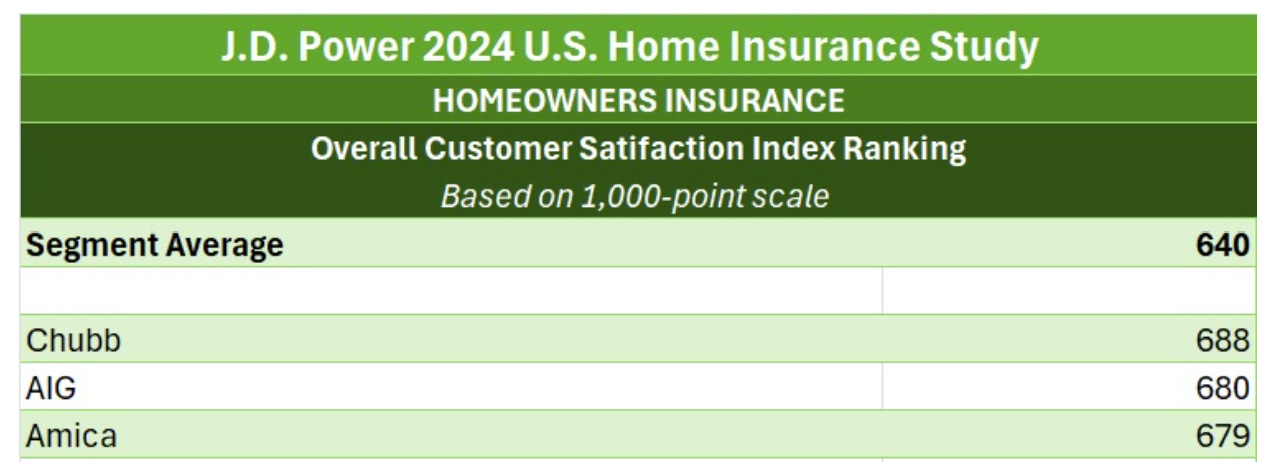

A more systemic complication to price-based disruption is end-user preference for other components of the value proposition. Just as consumers overpay for Starbucks coffee or Bentley cars, they are willing to pay extra for the exclusivity of engaging a wealth manager or investing in a hedge fund, even when a nearly free index fund could yield better returns. In the case of home insurance, affluent customers similarly prefer higher-priced, high-touch providers like Chubb. According to a recent J.D. Power consumer survey, Chubb received the highest customer satisfaction score:

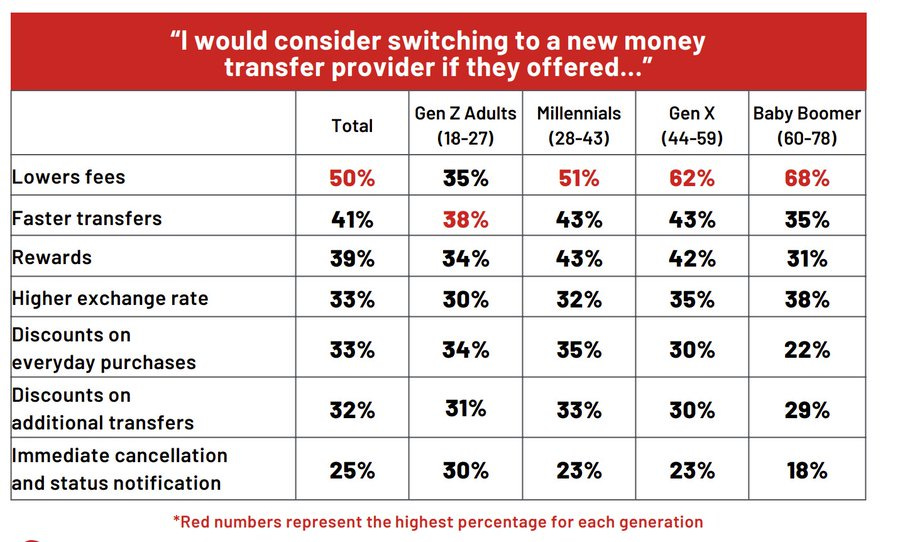

It's a common belief among experts that higher prices inevitably invite disruption from low-cost providers. They often overlook that consumer apathy is a powerful force. Moreover, the overall improvement in the value proposition of financial and insurance products over the last three decades has made consumers more satisfied with prices, shifting their focus to product features instead. This trend is particularly evident among Gen Z across various products, including money transfers:

Okay, but when prices rise rapidly, are consumers switching providers and embracing low-cost startups? Not necessarily. U.S. home insurance prices rose more than 11% in 2023, yet according to the same J.D. Power survey, less than 7% of consumers shopped around, and the switch rate, at 2.2%, was at historic lows. The reason lies in the system-wide root causes behind higher prices that traditional insurance carriers cannot out-innovate and that render insurtechs largely irrelevant. Higher property crimes, legal malfeasance, and unchecked construction in disaster-prone areas drive up costs for everyone.

What the government believes

While FSI executives grapple with these pricing complexities, U.S. politicians, regulators, and media across the political spectrum adopt a simplistic view. Some do not even believe that higher prices are driven by the rapid increase in the money supply; instead, they perceive a cabal of FSIs charging excessive prices. This perspective extends across industries, with claims that grocery chains, banks, and other providers are all ripping off consumers:

Even business media agree that FSIs are generating excessive profits with cushy pricing. They recently discovered that banks make more money when interest rates rise. Never mind that every neobank for consumers and businesses has enjoyed the same upside. Additionally, consumers have moved trillions into long-term CDs and money markets over the last couple of years. The lack of significant interest paid on checking account balances feels unfair:

In the U.S., such attitudes toward how FSIs price their products have already led to price controls on credit card rates, home insurance, and bank fees. But why stop there? Let’s use government intervention to cut prices in half or more, as Trump recently promised for auto insurance and credit cards:

So far, so good, but what if FSI executives refuse to offer their products to certain segments, citing the trite risk-based pricing logic? As is often the case, California—the laboratory of new economic theory—leads the way by experimenting with prohibiting such unempathetic behavior:

If you're bewildered by these developments, imagine how I feel—growing up in the Soviet Union believing that capitalism was the evil exploiter of the common people, then experiencing its enormous force for good, and now hearing communist tropes from political and media leaders in what is supposed to be the cradle of capitalism.

But let’s not lose hope yet. After a 50-year break, it's once again acceptable to believe that nuclear fusion generates more energy than windmills or glass. So maybe one day, it will be okay again to think that prices are determined by the interaction of supply and demand.

Balancing Digital Transformation Maturity and Strategic Ambition

Amazon recently made waves by behaving more like a bureaucratic behemoth than the trailblazer of target-state operating practices that leading FSIs and fintechs have tried to adopt over the past two decades. Its CEO, Andy Jassy, made two organizational decisions public:

Each group must increase the ratio of individual contributors to managers by at least 15%.

A uniform return to the office five days a week.

Two decades ago, if Jeff Bezos thought there were too many managers in a group or that teams weren't working effectively, he would have zeroed in on the specific areas where it was a problem. He’d have micromanaged the root causes, ensuring his leaders fixed the systemic issues. Now, nuance has been replaced with a blanket, one-size-fits-all approach, reminiscent of a bureaucratic government agency.

If even digital natives like Amazon fall victim to organizational entropy, it's no surprise when FSIs default to similar 20th-century solutions. HSBC just appointed another CEO, and, predictably, his first move is cost-cutting through restructuring and reducing management layers. Bloomberg recently reported specific ideas under consideration:

Combining commercial and investment bank divisions.

Cutting country managers.

Sure, country managers should indeed be the primary target of cost-cutting to prevent their local market knowledge from hindering groundbreaking ideas from HQ. But sarcasm aside, the moves by both Amazon and HSBC raise a bigger question: What is the ultimate goal of these changes in operating models? After all, neither Amazon nor HSBC is in urgent need of preserving cash.

As we've often discussed, most FSIs don't actually need to transform. Their current business model is profitable, the market is expanding, and direct competitors aren't 10x better in price, product features, or service quality to trigger a customer exodus. Plus, digital features can still be deployed, even with lower maturity levels. Yes, it may take longer and cost more, but many FSIs are making progress today by launching digital capabilities with a 20th-century IT Project operating model.

The lack of urgency for transformation is also fueled by the slow pace of change in consumer habits. For three decades, experts have predicted the death of bank branches, yet banks continue to make massive investments in their physical channels. Financial and insurance products remain highly complex for the average consumer, and decisions can be overwhelming. Despite being able to cash a check on their own, many still seek in-person advice from a human when navigating these complicated decisions.

There are still two key reasons to pursue the risky and painful feat of transforming the operating model: defensive and offensive. On the defensive side, UK consumer banks should be concerned about Monzo and Revolut, just as their counterparts in Brazil should worry about Nubank. Additionally, there are global instances where urgency exists within specific product niches, such as Western Union needing to stay competitive in digital maturity for international money transfers against fintech rivals like Remitly and Wise.

But aside from these cases, FSIs don't have to level up their operating models defensively. Even when necessary, digital transformation might only be required in divisions facing a credible threat of revenue loss from an advanced competitor.

The most exciting and riskiest reason for digital transformation is when a traditional FSI decides to go on the offensive—capturing market share or entering new markets not through M&A but with a superior business model. This is extremely difficult, as the operating model must be adaptable enough to meet local needs and navigate the competitive landscape. Failures over the past decade, even among leading neobanks like N26 exiting the U.S. and Brazil or Cash App leaving the UK, underscore these challenges.

Yet, as European neobanks Monzo and bunq now join Revolut and Wise in the fight for U.S. consumers, an unexpected player is striking back on their home turf—not a neobank, but Chase. Expanding its digital-only operations in Europe, Chase is adding a credit card and aiming to cover the entire continent.

Burning billions and competing against some of the world's best neobanks, Chase is attempting the ultimate feat. Using terminology from my 5-step digital transformation framework, Chase, a Level-4 player, is striving for a Level-5 achievement. With over $25 billion in deposits and 200,000 Nutmeg investment customers from its 2021 acquisition, Bloomberg recently reported that Chase is envisioning offering a full spectrum of financial products across Europe:

“We are not going to have branches or anything like that — it’s all digital,” Daniel Pinto, JPMorgan’s president and chief operating officer told investors at a conference earlier this month. “And at some point, we will expand into the rest of Europe.”

Chase's vision is so ambitious that it requires more advanced operating practices in Europe than on its home turf. There are precedents among global players like MasterCard and Visa, where their groups in some countries were more effective than at HQ, but they both operated at lower maturity levels. Hopefully, Chase understands how unprecedented its undertaking is.