Idiosyncrasies of the Digital Shift Demand FSI Executives Embrace Nuance in Transformation

Also in this issue: To Succeed in Digital Transformation, FSI Executives Must Unlearn Entrenched Operating Routines

Idiosyncrasies of the Digital Shift Demand FSI Executives Embrace Nuance in Transformation

Since the mid-1990s, digital experts have routinely predicted the demise of physical channels — bank branches, money transfer kiosks, and financial advisors. The logic felt sound: as digital experiences grow more seamless and helpful, why would anyone bother visiting or calling a financial services employee to complete the same task? Even in the '90s, it seemed absurd that paper checks were still in use for payments in the US. Surely, three decades later, they must have vanished. Well done, everyone.

This isn’t for lack of trying. Progressive Insurance, one of the world’s leading data analytics powerhouses in financial services, has more than doubled its auto insurance market share over the past 15 years. It is on track to overtake State Farm within the next couple of years. If there were a profitable way to accelerate that growth by abandoning traditional channels in favor of digital, it would have done so. Yet, Progressive still sells 45% of auto policies through agents and a striking 74% of home insurance, with no meaningful acceleration in the shift.

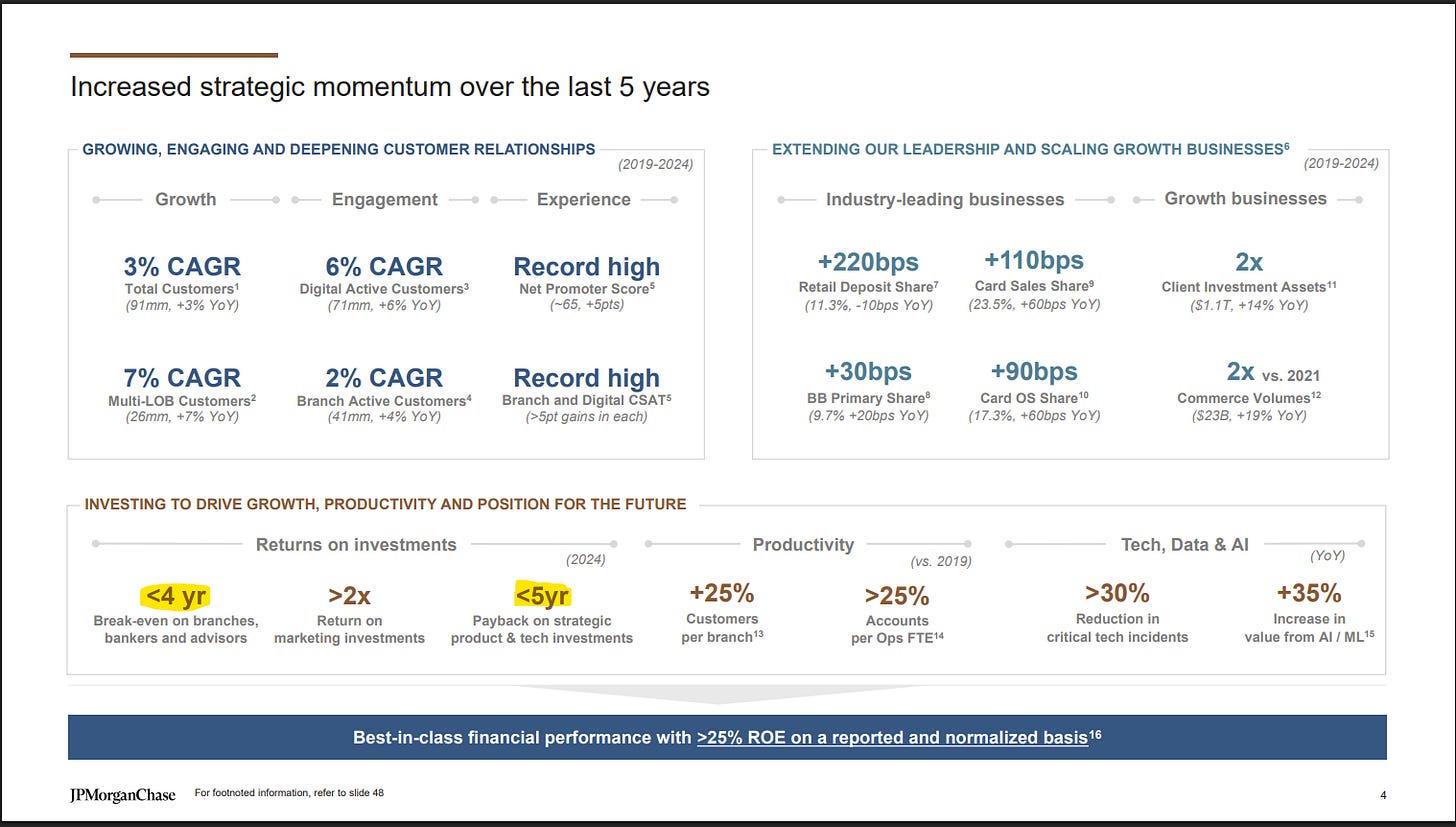

Consumer and business remaining preference for traditional channels forces FSIs to invest in both, albeit with a greater share flowing into digital. Bank of America, for instance, allocates $4 billion annually to new technology initiatives while investing $6 billion in its branch network since 2016. Although JPMorgan Chase holds its overall branch count steady, it has opened nearly 900 new branches in the past five years and continues to grow its field headcount by 4% annually.

Why would a digitally advanced FSI like JPMorgan Chase keep building new branches and expanding field staff in the age of digital disruption? Because they are profitable. Even more jarring to fintech experts, JPMorgan consistently sees faster, more reliable returns from branches and field staff than from strategic products and tech investments, with branches delivering payback in under four years, compared to under five for tech initiatives.

FSIs obviously aren’t curbing the endless flood of irrelevant credit card offers out of environmental concern — press releases aside, that’s not the driver. And you’d think they’d stop annoying customers for the sake of experience in the era of customer centricity. But of course not. Despite billions poured into analytics, direct mail targeting hasn’t meaningfully improved. It doesn’t have to. With an average response rate around 0.5%, one new customer offsets the cost of mailing to 199 others. Plus, FSIs know people like me won’t sever current or future relationships just because we keep getting irrelevant offers every quarter for eternity.

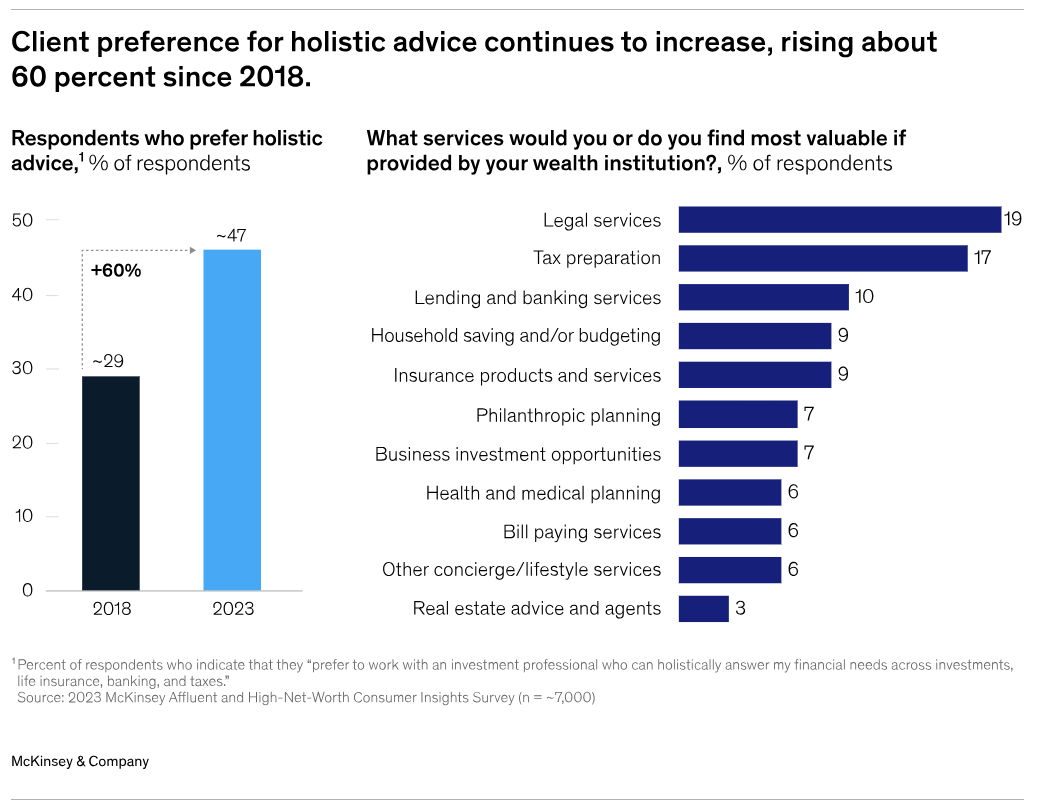

Top fintechs also get the value of traditional channels and aren’t clinging to a “digital-only” mantra. It’s widely understood that digital self-service is especially questionable when targeting high-end clientele. Even Betterment, the poster child of robo-advisory, has built a 33-person investment advisory team. As FSIs and fintechs explore digital plays for wealthy and business segments, they run into two inconvenient truths: these clients still value human connection, and their biggest pain points usually lie outside the financial and insurance products.

That preference for traditional channels extends to both acquisition and servicing. Despite the GenAI hype, chatbots mostly remain glorified FAQs and consistently rank as the most disliked feature in FSIs. While it’s harder to make the economics work, especially for lower-income segments, high-quality human support, not chatbots, remains the real differentiator. Even among newly launched wealthtechs, firms that are seeing traction are pairing digital convenience with responsive, capable human advisors.

Wise, one of the world’s most effective fintechs, is learning that too. It built a global market-leading position in the expat segment for money transfers and multi-currency accounts while spending a tiny fraction of revenue on marketing. However, to sustain rapid growth, Wise recognized that some consumer and business segments won’t convert without human persuasion. As a result, it’s finally scaling up marketing spend and investing in physical channels like partnerships and in-person events.

While the shift to digital in financial services and insurance remains invisible or gradual for affluent consumers and businesses, it’s happening much faster in lower-income segments. For example, paper checks still see demand among small businesses, yet migrant remittances are reliably moving to digital. As Intermex CEO Robert Lisy noted on the Q1 earnings call:

“… it's challenging when the overall market is flat and you see digital as an industry maybe growing 30%, it tells you that the retail market is probably growing at a minus 8% or minus 10%.”

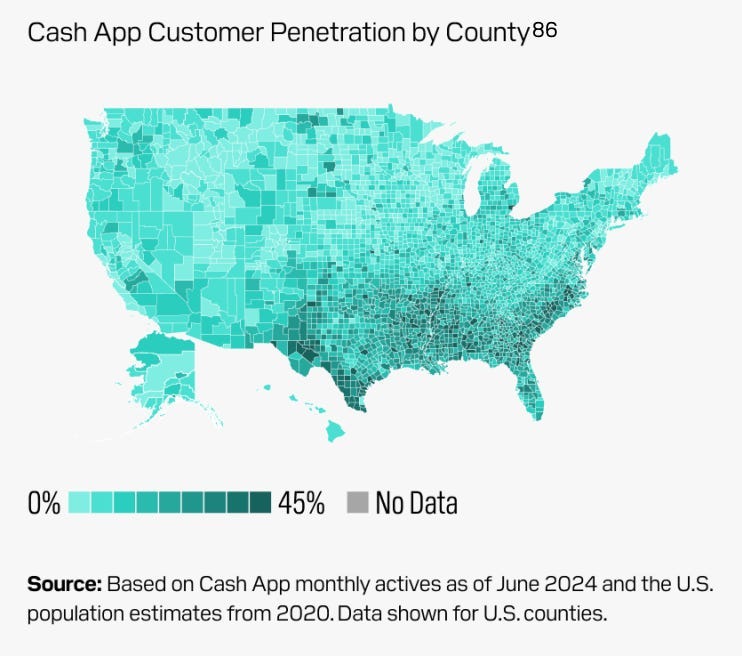

Cash App is among the best illustrations of rapidly expanding digital financial products for low-income populations. While many traditional FSIs and fintechs talk about serving poor black communities in the US South, Cash App’s penetration in some areas has been remarkable. According to the company, monthly active users in certain counties have reached 45%.

Cash App and Chime dominate the low-income gig worker segment directly, while fintechs like DailyPay, Payactiv, and Rain reach this market through employers’ HR departments, then bundle additional products for end customers. DailyPay alone serves more than five million users after a decade. Among Cash App’s monthly active users, 24% have incomes under $35K, compared to 18% of financial services users in the U.S. overall.

The seemingly paradoxical persistence of traditional channels and idiosyncrasies makes prioritizing top-line use cases for digital transformation far more complex than many FSI executives prefer. Each customer and business segment shifts at its own pace and not in a straight line. Deploying the same digital feature across the board would overwhelm some segment-product intersections and fall short for others. Unfortunately, for FSI C-suites, which typically favor simplification, their digital transformation strategy must be highly nuanced.

To Succeed in Digital Transformation, FSI Executives Must Unlearn Entrenched Operating Routines

Digital transformation aims to accelerate business value capture by transforming the operating model so an FSI can better leverage digital capabilities. While our newsletters often cover the excruciating difficulty of the “transforming” part, the starting point must be a relentless desire from the C-suite and board to accelerate revenue and profit growth. If they have no plans to replace executives as long as the current growth trajectory holds, the last hope lies with business heads eager to drive faster growth. If they don’t care for either, digital transformation is unnecessary.

FSI boards and C-suites rarely have the appetite to pursue accelerated growth at the cost of overhauling the operating model and taking on more business risk. Most traditional FSIs are content with low single-digit revenue growth and high single-digit net income growth. Combined with fatigue from repeated failures in data and tech modernization, there is little rationale for pushing the pace. In a recent Forbes interview, Andrew Foster, Chief Data Officer at M&T Bank, illustrated this experience:

“I was at an offsite with bank executives, and asked, ‘Put your hand up if you've seen a failed data program at this bank. These are deeply tenured people. Then I said, keep your hand up if you've seen two. And when I got to about four, most of the hands are still up.”

Most FSI executives resist transforming how they personally operate because they grew up in the existing model, developed muscle memory, and believe it works well. Especially in smaller FSIs, some business leaders still see technology and data capabilities as a necessary evil. When I recently asked the CIO of a small US bank if he cared about digital transformation, he replied, “It’s tough to drive digital transformation when your 70-year-old CEO tells you he hates IT.”

Unfortunately for IT and data heads, the operating model for digital transformation must be business-led. Even IT modernization initiatives, like core systems replacements, should ideally be driven by the business, as IT cost savings alone rarely justify such changes. In a recent interview with CIO Online, Alex Smart, CTO of Southern Cross Travel Insurance, shared several best practices for structuring the operating model in these situations:

"You don’t go down a transformation path unless you have a really painful problem to solve, because it’s not an easy thing to do"

"The whole business was transforming. We were ripping out its core foundations, so the board was very interested in how it was going to go"

"At the executive level in our business, we share our KPIs, so I don’t have separate ones from a CFO or my COO"

"A transformation project isn’t my KPI to deliver. It’s for all of us to deliver"

"We reorganized ourselves about four times as we moved through and learned things, and ran into different obstacles and broke through obstacles, refining our scope"

"Assemble a small group of people highly skilled in those capabilities to form a lead team."

For leading FSIs, pursuing IT modernization alone is not an option. They must accelerate revenue growth, ideally with the CEO driving the transformation. Despite being owned by legendary Buffett, GEICO fell behind several years ago. They brought in a new CEO, Todd Combs. As a result, GEICO’s 2020–2024 turnaround serves as a benchmark case of CEO-driven transformation: scaling data analytics and technology not for digital bells and whistles, but to accelerate top-line growth while cutting headcount by 40%.

“Todd has done a great job in turning around the operations. When he took over, there were two major issues that GEICO was behind its competitors on. First, the term we’ve been using is “matching rate to risk,” and second, telematics. We were at the bottom of the list in telematics about five or six years ago. Since then, we have made rapid strides. Telematics, which used to be a source of competitive disadvantage to us, is no longer so, and I would argue that our telematics at GEICO is about as good as anyone else’s today.”

What makes examples of business-led digital transformation with clear value capture so rare? It’s obvious that CEOs and business leaders are best positioned to drive transformation hands-on, since the journey involves high risks of wrong assumptions and requires frequent adjustments. Yet this clashes with decades of muscle memory—a traditional approach where business teams define requirements and IT implements them in silos, periodically showing work and hoping they’ve understood the business correctly.

The key skills to succeed in traditional FSIs are internalizing the evolving zeitgeist and carefully improving the status quo. In top fintechs, that mindset must be unlearned in favor of first principles thinking. That’s why there’s almost no cross-pollination between the largest FSIs and leading fintechs; executives from either side are often seen as resume harvesters or troublemakers.

Another entrenched routine is how traditional FSI executives manage their reports. At best, they provide periodic, insightful feedback; interactions often consist of status updates and light coaching. Sometimes they even publicly criticize their teams. At a recent town hall, JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon boasted he could do his reports’ jobs better himself.

In digital transformation, the executives' number one job is to level up themselves first, then their reports and peers, so the organization can operate at a higher digital maturity. Success is measured by accelerated profits and, eventually, making the executive redundant. This is easier when such principles are established from the start, but that rarely applies to traditional FSIs. So, how can they change company culture even when there’s a genuine desire to pursue digital transformation for financial results, not just vibes?

That is a difficult question even for digital natives and well-known fintechs like Block, which struggled to transform via the so-called “founder mode.” The inherent fallacy lies in hoping that a founder re-learning the intensive management style that made them initially successful will be sufficient to inspire others to level up. But that only works in short bursts to replace managers who can’t continuously raise the bar. Unending micromanagement halts scaling velocity, whereas the best fintechs like Revolut scale by amplifying autonomy.

Without a CEO willing to invest in leveling up their reports, the next best option is for each executive to learn from more advanced peers. For example, if you’re in auto insurance, do you know how your counterparts at Progressive or GEICO spend their day? There’s usually more transparency from top fintechs. Common excuses from FSI executives for not learning from fintechs like Revolut include: 1) they’re smaller, 2) they offer fewer products, and 3) they’re less regulated. That might have been true five or ten years ago. Today, Revolut operates in 50 countries with $4 billion in revenue, $1 billion in net income, 70% growth, and a 10,000-person workforce—40% of whom are in compliance.

The real issue is that adopting fintech-style ways of working means radically changing entrenched routines: fewer status meetings and recycled strategy decks, and much more time spent deep in playbooks, UX, data, and even code. If your FSI is serious about digital transformation, are you willing to let go of old habits and embrace those of your peers from leading FSIs and the best fintechs?