In Digital Transformation, Target Metrics Are Only as Effective as Executive Incentives to Achieve Them.

Also in this issue: Should FSIs Prioritize Stablecoins in Their Digital Transformation Strategies?

In Digital Transformation, Target Metrics Are Only as Effective as Executive Incentives to Achieve Them.

The financial services and insurance industry doesn’t need external examples to understand the impact of perverse incentives. Scandals like Wells Fargo’s cross-selling, PPI mis-selling, AIG swaps, Libor manipulation, and subprime mortgage crises serve as regular reminders that lofty statements about “values” and “culture” are secondary to how employees are compensated. In digital transformation, capturing marginal effectiveness requires more than adopting novel technologies or reorganizing for cross-functional collaboration—incentives must also change at every stage.

Financial crime illustrates the nuanced nature of incentives. Money laundering often brings in revenue from low-maintenance customers, leading banks to prioritize regulatory compliance over proactive deterrence. Similarly, credit card chargebacks mirror this dynamic. While issuers and processors might identify repeat offenders driving a 75% friendly fraud rate, they lack sufficient incentives to debank these cardholders without regulatory pressure.

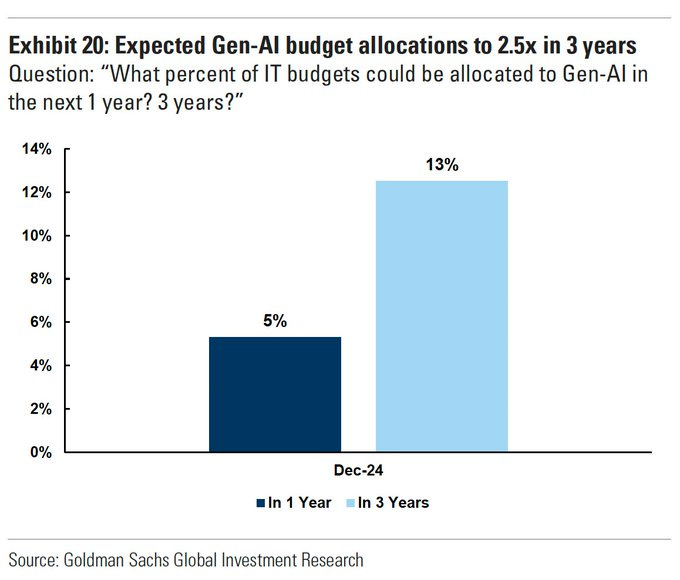

In the context of digital transformation, the Generative AI hype underscores the critical role of incentives. Much like the brief period around 2017-2018 when FSIs experimented with blockchain, GenAI remains a largely unproven technology from an ROI perspective. However, while blockchain initiatives were typically treated as R&D with budgets under a million dollars, two years since the public release of ChatGPT, most large FSIs are now investing millions—sometimes tens of millions—in GenAI. These investments are poised to accelerate further, mirroring trends across nearly every other industry.

A large FSI spending 1% of its revenue on GenAI would mean tens or even hundreds of millions annually within a few years. Which executive should be incentivized to ensure ROI on such a significant investment? From my conversations with FSIs, most don’t have a clear answer. Their GenAI products are usually unprofitable, with only a few niche exceptions. Business heads prefer IT to absorb the rapidly rising costs of licensing, storage, and staff, while IT leaders lack the authority to drive returns within business groups.

Ongoing cloud migration serves as a cautionary tale of how not to approach incentives. “100% Cloud” and “Cloud First” were correctly championed by CEOs and often supported by an evolution toward cross-functional teams. However, the absence of aligned incentives left most FSIs unable to estimate the ROI of their massive cloud investments. CIO Online recently highlighted a typical example in an article titled “Discover’s Hybrid Cloud Journey Pays Off.” Here’s how Discover Financial Services CIO Jason Strle described that “pay-off”:

“Due to the elasticity of the environment, we were able to handle circumstances such as big surges, and that’s very important to us because of the way we do marketing and campaigns and different ways people interact with our rewards. That can lead to very spiky consumer behavior, and we can dynamically grow our capacity on public clouds.”

Using other people’s computers to offload spikes in capacity requirements is a marvelous idea—if the benefits outweigh the upfront costs. However, they often don’t, or at the very least, present difficult trade-offs. A year ago, Allianz Technology CTO Axel Schell provided rare transparency on the ROI of their cloud migration:

The core project team consisted of around 500 employees while around 3,000 people worked at times in various phases, and the budget was a low, three-figure million euro amount. Bearing that in mind, the project plan is for it to pay for itself after three to four years. “We’ve been running the platform for a year now and can see exactly how it compares to the mainframe costs,” says Schell. “We save a double-digit million amount in operation.”

An FSI might still pursue investments where upfront costs exceed annual benefits by 5-10X, but incentives must align with the owner of those benefits. If the savings primarily come from IT, then the Head of IT’s compensation should depend on the success of such a massive investment. If the significant scalability gains come from avoiding additional hires in business and operations, then those executives should be incentivized to meet growth or support targets without expanding staff.

One of the interesting nuances of incentives in digital transformation is the role of employee satisfaction. While it may appear to be a sensible target for executive incentives, it may not be a practical approach. First, the required changes to the operating model often create significant turmoil, so a drop in employee satisfaction is expected by design. Second, even some of the world’s most effective fintechs have found that hiring mission-driven employees is only feasible in their earlier years. At a particular scale, they inevitably hire staff who see the role as just another job and aren’t particularly enthusiastic.

As a result, the historical advantage fintechs had over traditional players in employee satisfaction has primarily disappeared—for example, in consumer cross-border transfers. Instead of incentivizing broad employee satisfaction, FSIs in the more advanced stages of digital transformation should focus on maximizing retention among top-performing employees.

Clearly defining digital transformation metrics and aligning executive incentives to achieve them with a positive ROI while retaining top talent can set an FSI apart from peers who haven't updated their incentives in years. For less ambitious FSIs, this may seem unnecessary—until profits drop. This is especially true for ambiguous programs like GenAI, which can be hidden within broader, fast-growing expense categories like computing costs—already the second-largest expense after personnel in some larger FSIs.

Should FSIs Prioritize Stablecoins in Their Digital Transformation Strategies?

By early 2018, it became clear that traditional cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin were not superior to fiat in addressing the remaining pain points in payments and transfers. As a result, most crypto fintechs either shut down or pivoted to trading and investing. Around that time, stablecoins began to emerge as a potentially better alternative, with some experts believing that the volatility of traditional crypto was the main barrier to adoption.

These days, stablecoins are a regular fixture in the news, with announcements of production-ready efforts by FSIs, regulatory approvals for fintechs, adoption by tens of thousands of businesses and consumers, and M&A activity. Recently, Coinbase's CEO shared a Circle post highlighting a new a16z report on stablecoin superiority, emphasizing the inevitability of a stablecoin-based future.

It’s easy to dismiss such prophecies as a circlejerk among companies with vested interests in the success of crypto. However, serious efforts are now being extended to traditional FSIs and fintechs. One of the most notable examples is JPMorgan’s Kinexys, which handles over $2 billion in daily transaction volumes and has processed over $1.5 trillion on its platform since its inception. Additionally, Stripe, a leading fiat processing fintech, recently paid $1.1 billion for stablecoin processor Bridge, referring to stablecoins as "room-temperature superconductors" for financial services:

While the use cases for financial services within the Web3 ecosystem are clear, they remain too small and too much in the "gray" area to attract significant interest from traditional FSIs as they prioritize digital transformation use cases. On the other hand, securities issuance and collateralization are viable for leading FSIs in that segment. But what about more mainstream use cases in payments and transfers, where stablecoins are promised to offer free and instant transactions?

While each player claims their stablecoin addresses issues for underserved consumers and small businesses, the growth of fintechs, Swift, and local payment rails has made these pain points increasingly niche. Instead, the business model revolves around consumers exchanging fiat currency for stablecoin and then holding or trading it across crypto.

PayPal’s stablecoin, PYUSD, serves as the best illustration of the difference between the nebulous positioning of stablecoins and the financial reality. If stablecoins were a superior payment and transfer rail, it would make sense for PayPal to use them instead of traditional infrastructure, potentially driving competitors without private stablecoins out of business due to an inability to compete on price and speed. Instead, PayPal continues to rely on fiat rails and has even increased prices for some of its products by over 40%:

PayPal’s remittance subsidiary, Xoom, would seem to be an ideal candidate for transitioning from traditional Swift rails to a stablecoin infrastructure. However, instead of integrating PYUSD-based transfers into their core service, PayPal has positioned it as a separate product that customers must opt into rather than making it a seamless feature within their traditional offerings. While HSBC’s Zing allows customers to convert FX pairs for a 0.2% fee, and Wise offers a similar service for 0.6%, Xoom remains one of the more expensive remittance fintechs, and PayPal charges 1.45% to convert PYUSD to another crypto.

For FSIs involved in trade payments, the pain points faced by their business customers are often more complex and not necessarily tied to the underlying payment rails. After Swift has made significant strides in improving interbank transfers since 2017, the focus is now shifting toward addressing the challenges in trade payments:

At the same time, the proliferation of digital platforms, standards and proprietary APIs means there is a significant risk of fragmentation. Other obstacles include the lack of recognition of electronic trade documents in some major trading nations. As such, trade digitisation will require not just technology, but also legal harmonisation, the adoption of common standards, and collaboration across the industry.

With ERP players like SAP and Oracle digitizing trade instruments for decades, global banks deploying APIs to facilitate standardization, and Swift harmonizing global payments, stablecoins have little to tackle. Rather than prioritizing stablecoin use cases for payments and transfers, traditional FSIs should focus on monitoring which products are beginning to lose customers to fiat-based fintechs. While this might not offer a significant business upside, it could help minimize the exodus of volume from traditional niche cash cows.