Should FSIs Embrace the Joy of Enterprise Bureaucracy or Make Agile Great Again?

Also in this issue: FSIs Should Worry Less About Wars—and More About Competing with Superb Fintechs

Should FSIs Embrace the Joy of Enterprise Bureaucracy or Make Agile Great Again?

Over two decades ago, Amazon demonstrated the effectiveness of autonomous, agile, cross-functional teams empowered to operate as mini-business units. A decade later, Spotify showcased how to scale this operating model. "Agile," shorthand for such playbooks, seemed destined to become the standard across FSIs. But is it?

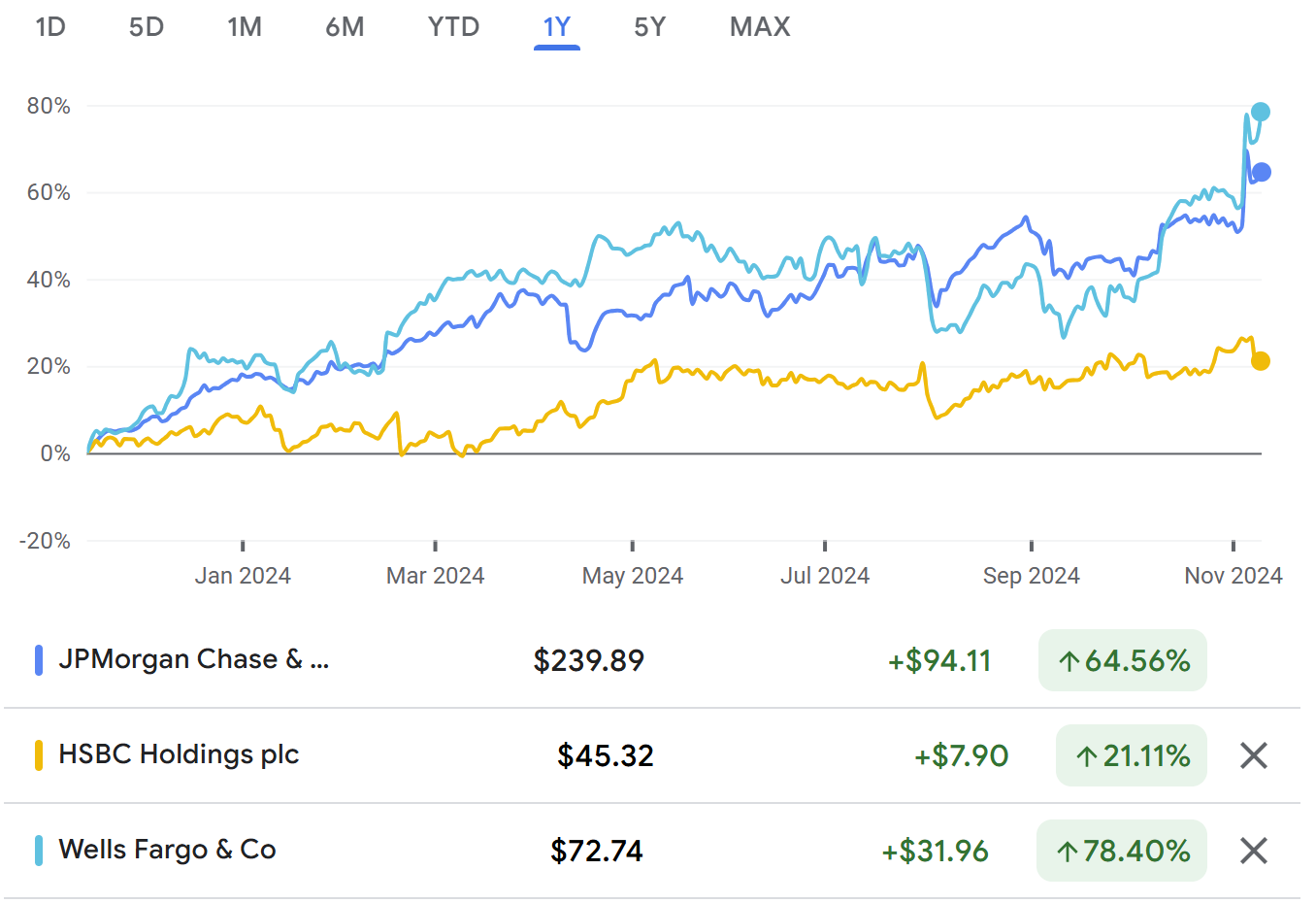

Consider ventures like Chase’s digital expansion in Europe, HSBC’s Zing, and Wells Fargo’s Bilt card. None followed agile tenets or Reid Hoffman’s famous advice, “If you’re not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you’ve launched too late.” Instead, each was a massive bet with top-tier UX from the outset, backed by investments ranging from $100 million to $1 billion, with unit economics stabilization as a later priority.

In a recent 11FS interview, Chase UK CEO Kuba Fast shared insights from three years into Chase's decades-long goal of becoming a top-5 European retail bank:

Success hinges on a high-performance culture at the enterprise level that enables divisions to operate at varying speeds.

Instead of duplicating distribution efforts (as seen with the Finn project), leverage the core brand and processes, supplementing only with new or enhanced components.

Launch big, with a strong UX out of the gate (ranked top-3 in the CMA survey), then focus on optimizing for unit economics.

For an FSI like JPMC, generating around $50 billion in annual net income, a billion-dollar upfront investment is feasible—and investors reward such large FSIs to make these offensive moves, rather than risk fintechs chipping away at their core business.

A more nuanced question is whether these big-bet divisions operate with agility post-launch. Are they empowered to control their trajectory, or are they forced to rely on shared enterprise services? As Goldman Sachs and Apple learned with the Apple Card, even high-performing digital players can face terminal setbacks when critical decisions are subject to enterprise-level bureaucracy.

The answer isn’t solely shaped by the preferences of the C-suite. A significant constraint arises when FSIs aim to elevate from an IT Product model to a Value Stream & Platform model: many LOBs lack the talent experienced enough to execute at such a high level of digital maturity. Monica Caldas, one of the most respected CIOs among US FSIs, inadvertently highlighted this challenge on a recent Tech Whisperers podcast:

“I was trying to understand underwriting in our Canadian operations. I flew to Canada, and I sat with the underwriters to understand why this capability we deployed wasn’t being used. The underwriting community was saying, ‘Well, it’s hard to use. It’s sometimes slow.’ And in technology, you can easily jump to, ‘Okay, let me solve for latency. Let me solve for user experience.’ In that example, it was better to just go and understand what is happening locally.”

A decade ago, for an FSI transitioning from an IT Project to an IT Product operating model, this would have been seen as an admirable example of a hands-on Global CIO. While it may not align with the Elon Musk level of ownership or the fintech-style C-suite behavior of coding and directly addressing customer complaints, it was still an improvement over the typical FSI CIO. Monica both tracks the adoption of new digital capabilities and gets personally involved to understand why they might not be used.

Today, for an enterprise CIO at a top-10 player like Liberty Mutual, this story highlights a significant gap in the operating model. Why was that underwriting capability deployed without ownership by the Canada operations? Why did it take a Global CIO to address the lack of adoption? The answer is typically two-fold: enterprise groups like IT hesitate to grant autonomy to LOBs, citing efficiency concerns, and front-line teams often lack the expertise to launch and scale impactful digital products.

In digital transformation, Effectiveness >>> Efficiency. The evolution to a cross-functional operating model typically begins within IT and Data groups. For instance, JPMC integrates cybersecurity teams early in the design and development of new applications. This approach contrasts sharply with the siloed operating models common in FSIs, which often result in poor UX for employees and vendors—a problem that will only intensify with the growing use of internal and external microservices. Pat Opet, the global CISO, discussed their operating model in a recent interview with Fortune:

As new tools are rolled out and employees get access to more forms of technology, Opet deploys a “federated” approach to cybersecurity. The CISO has a team of security architects and engineers who are embedded into the development teams to build the necessary safety controls of the latest generative AI tools or cloud platforms.

Some FSIs, like AIG, are now establishing cross-functional hubs that include business owners, shifting away from the previous view of the Ops and Data/Tech groups as cost-saving targets for relocation and outsourcing. Instead of deploying new capabilities in an IT enterprise vacuum, AIG has recognized that only in-person, cross-functional setups give employees a fair chance to level up their operating muscles:

AIG is expanding its operations in Atlanta and hiring local talent for various roles across underwriting, claims, operations, data engineering and AI. The new hub will enable these co-located teams to incubate digital capabilities, test new processes, and collaborate more seamlessly across functions, accelerating innovation to promote growth and drive scale for AIG’s core businesses.

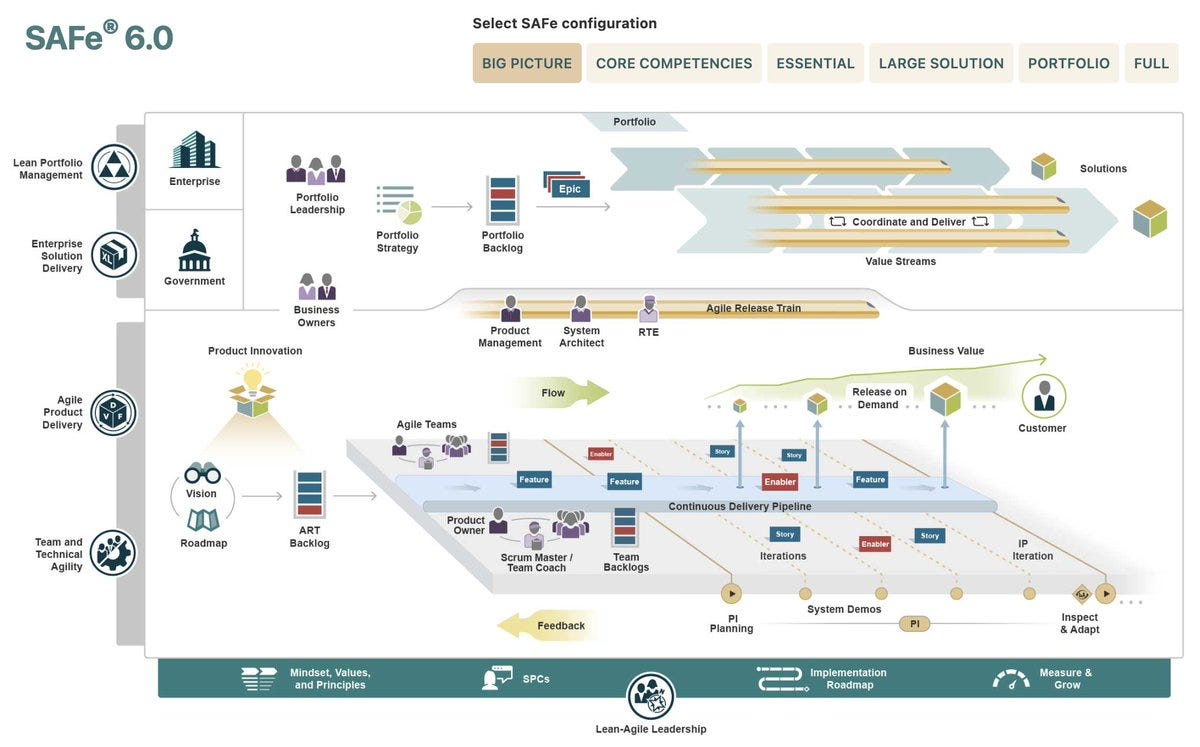

The shift from enterprise bureaucracy to LOB enablement is incredibly challenging. In my experience working with large FSIs, well-meaning middle managers are often overwhelmed by detailed policies and procedures, leaving them unable to embrace change or take risks with creative solutions. In turn, their C-suite hesitates to trust them with more autonomy, instead continuing to rely on opaque, pseudo-agile models like SAFe—essentially a glorified 20th-century IT project management approach.

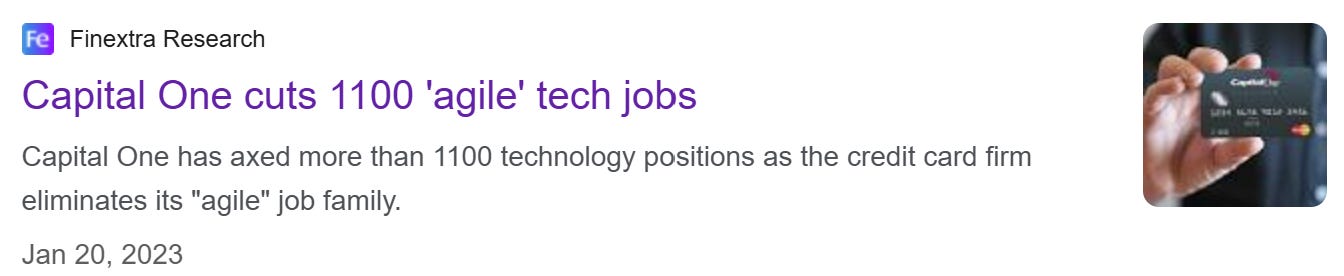

Instead of making digital-related roles, including "agile" positions, permanent fixtures at the enterprise level, ambitious FSIs that make big bets should treat them as temporary ones to accelerate transformation in LOBs. Liberty Mutual’s enterprise groups should assign experts to help Canada’s underwriting learn what good looks like enabling them to launch products independently. Once this knowledge is disseminated, those coaching agile roles are no longer necessary, as Capital One demonstrated in early 2023.

Transitioning from the Joy of Enterprise Bureaucracy to Making Agile Great Again will be difficult for any organization, even leading fintechs like Block. Fortune recently reported that, while Block continues streamlining and its stock remains 70% down from all-time highs, employees weren’t allowed to mention a failed venture with Jay-Z and were required to display outward happiness. Unfortunately, unlike the government, FSIs and fintechs can’t afford to make big bets without facing the significant pain of fully embracing the original vision of Agile:

People present explained that the CEO kicked off the meeting by complaining about perceived “negativity” from staff, saying that he wanted more positivity. Dorsey then handed off the meeting to other Block executives who were told by Dorsey to answer the question, “Why are you happy you’re here,” according to the people present.

FSIs Should Worry Less About Wars—and More About Competing with Superb Fintechs

When FSI titans like Ray Dalio or Jamie Dimon make alarmist pronouncements about impending calamities like civil war or World War III, it inadvertently challenges the stereotype that Gen Z is uniquely prone to catastrophizing. And for all the criticism directed at fintech founders who have milked the supposed tragedy of the "unbanked" in developing countries while serving affluent consumers in the West, at least they don’t indulge in the “The War is Coming” rhetoric.

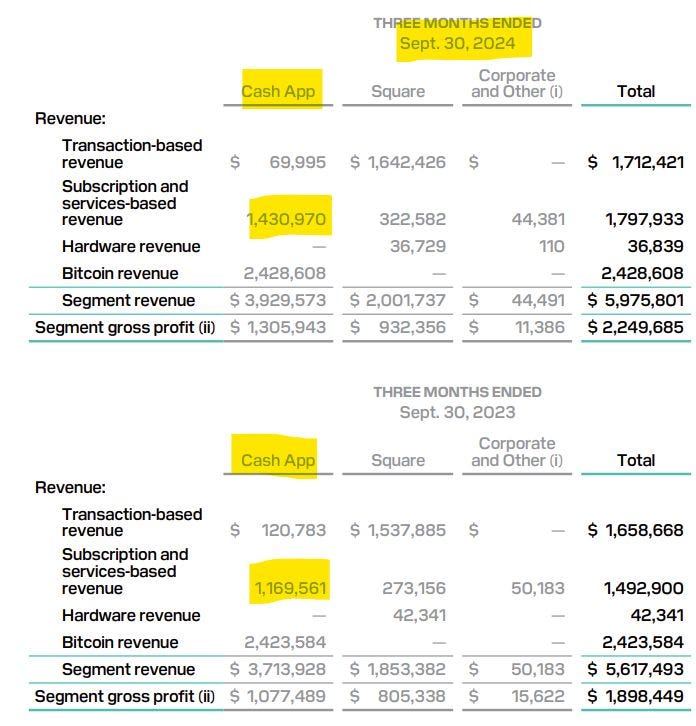

There isn’t even a true war between incumbents and fintechs. JPMorgan Chase is approaching a trillion-dollar market cap, and Bridgewater Associates, despite a decade of mixed performance, still manages $120 billion in assets. Their fintech competitors are also thriving. For example, Betterment now manages $50+ billion. Cash App stands out as the only remotely feasible banking disruptor in the U.S., with B2C fiat revenues growing at around 20%. Already a top-10 consumer bank, it’s on track to surpass the #9 player, TD US Retail Bank, by 2027.

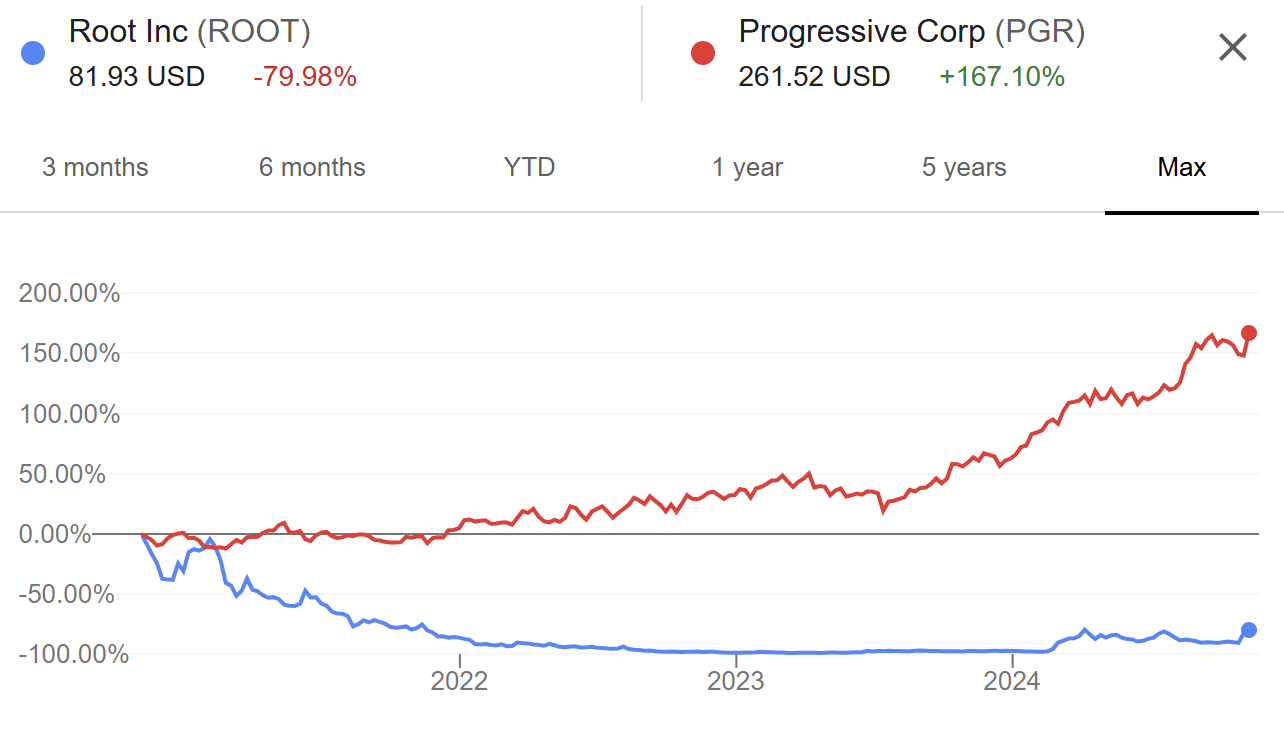

In insurance, the most successful player was founded in 1937. While insurtechs struggle, Progressive Insurance steadily gains 0.5–1% market share annually and now holds around 16% of the U.S. consumer auto insurance market.

FSIs shouldn’t worry about losing a war with fintechs unless they operate a vulnerable monoline or a product area targeted by ambitious, specialized fintechs. With its superior UX and analytics, Rocket Mortgage has become a leader in the U.S. mortgage refinance market, reaching a 17% market share in 2023 at the expense of traditional banks, including top players like Wells Fargo.

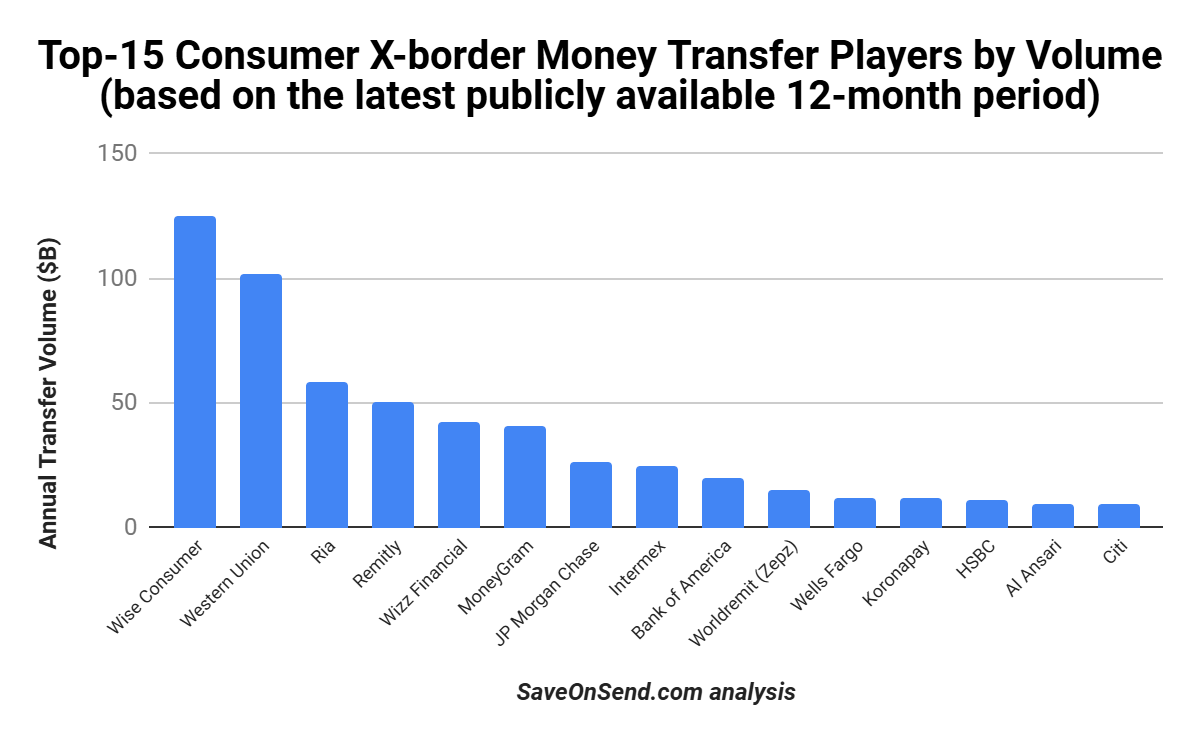

Another such market segment, on a global scale, is consumer cross-border money transfers, where there have been casualties among both traditional players and fintechs. Azimo was acquired by a payroll company to salvage some of its payment technology, MoneyGram was taken private by a PE firm, and Intermex is likely next. Small World and Sigue have disappeared. Western Union and many top banks have also seen declines in transfer volume in recent reporting periods. As Wise and Remitly continue to grow rapidly, fiercer battles among the top players are likely ahead.

FSIs will continue losing local battles as they can’t match the superior, more effective operating models of specialists. Wise, for example, acquires 70% of new customers through referrals, while the customer acquisition cost for traditional providers is $30–40. As fintechs scale, incumbents in these markets can’t achieve a price advantage with partners. Remitly CEO Matt Oppenheimer highlighted this shift in a recent interview with FXC Intelligence.

“As we get more scale, the great thing is we can drive down costs in the industry. Having done this for close to 14 years, I can tell you the deals that we got when I said, “hey, we’re going to send you 50 transactions next month” versus [those now with] millions of transactions flowing through our platform.”

At some point in the future, there might even be a battle between top fintechs. While Wise and Remitly initially targeted different customer segments over a decade ago, their massive scale and continued fast growth have already led to some overlap in use cases. A fintech expert, Jevgenijs Kazanins, recently caught a battle cry from Max Levchin, Founder of American Affirm, during a recent earnings call on the BNPL war with European Klarna:

“The battle has been brought to us in the U.S., we held off the onslaught better than I think anybody expected and continue to do so. We're bringing the battle to them in Europe in the U.K., not the other way around.”

Hopefully, your FSI is as solid across core products as Progressive in U.S. auto insurance. In that case, you won’t need to worry about wars with or among fintechs—you can sit back and watch them battle it out elsewhere.