Labor Arbitrage Disguised as Digital Transformation in FSIs

Also in this issue: Key Factors FSIs Should Consider to Determine If Disruptors Are a Threat

Labor Arbitrage Disguised as Digital Transformation in FSIs

While the number of Indian migrants working in the financial services and insurance industry has visibly grown since the 1990s, the scale became evident during my trip to American Express in Arizona a decade ago. When visiting clients, I often walked the floors to observe workplace culture, and among hundreds of employees, scarcely any appeared to be non-Indian.

Three decades ago, companies were as optimistic about outsourcing IT roles as they are today about LLMs producing high-quality code with minimal oversight. Many began betting that replacing a costly American engineer in NYC with a more affordable Indian migrant in Phoenix, supported by an even cheaper offshore team, would entail minimal trade-offs. Today, around 400,000 H-1B petitions are approved annually, with the average compensation for H-1B visa holders at approximately $120K.

This shift in workforce composition, which accelerated about 20 years ago, has occurred without Indian candidates being included in diversity hiring campaigns, despite technically qualifying as “people of color.” Unlike a female candidate from a wealthy U.S. family or a black candidate from an affluent Tanzanian family, the virtue-signaling value of an Indian raised in the slums of Mumbai is seen by FSI executives as equivalent to that of a white candidate who grew up in the shantytowns of Appalachia—essentially none.

The broader debate about hiring migrants went viral recently when Trump’s efficiency lieutenants, Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, publicly supported increasing the hiring of top-tier migrant candidates. The discussion has revolved around whether such hiring is driven by labor arbitrage, a shortage of specialized U.S. graduates, or perceptions that Americans are less hardworking or obedient.

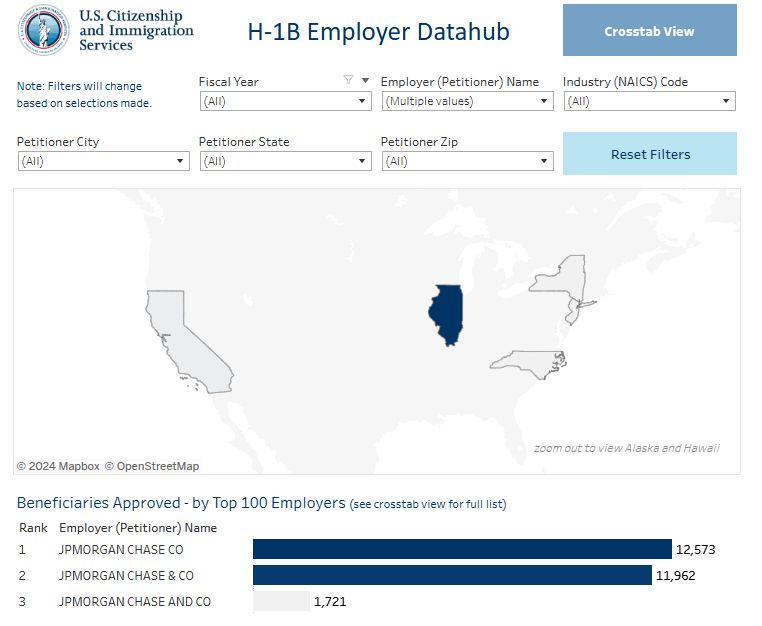

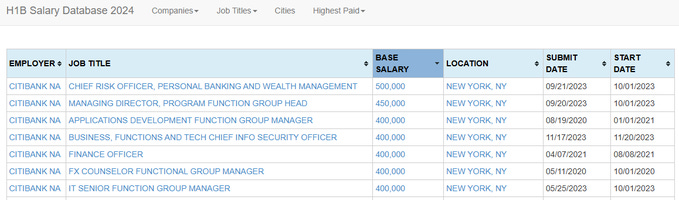

These hires span a variety of functions, including risk and marketing, but the majority are concentrated in IT. Indian outsourcing giants dominate this space, though high-tech firms, the Big Four, and FSIs also play significant roles. For instance, in the past 15 years, JPMorgan Chase has secured approval for more than 26,000 H-1B hires:

Numerous FSIs are among the top 100 U.S. employers with the most H-1B approvals in 2024. They include major banks, Fidelity, PayPal, and Visa. The roles range from entry-level to C-suite, with salaries from $60K to $600K.

While Indian outsourcing firms might be seen as providing obedient, cost-effective mediocrity, Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy argue that they seek only elite, high-cost migrants from "the top 0.1% of engineering talent" with a "culture of excellence." Think of Sundar Pichai, but from a gene pool like Lee Kuan Yew's, earning at least $400K. Elon’s transformation of Twitter into X seems to support the idea that top-tier engineers are so effective that eliminating 80% of the workforce has no downside—and feature velocity increases dramatically.

Isn’t that the ultimate vision of every FSI in digital transformation—to become a technology company like X, where a small team of elite engineers oversees AI agents? Perhaps, but in the meantime, the opportunity to cut labor costs across various roles is far too tempting. Even Musk hires migrants for a wide range of positions, IT and beyond, with starting salaries as low as $70K:

In my client interactions, I often meet exceptionally bright migrants, but this employee segment isn’t significantly more effective on average. Over the years, I’ve seen large FSIs replace their American IT staff with outsourcing firms, promising Wall Street substantial savings. In some cases, the strategy worked; in others, costs increased, and quality suffered. I’ve also observed modernization projects where small teams of employees and vendors were replaced by much larger outsourcing teams, often resulting in failed implementations.

Due to their short-term advantages, FSIs will likely persist with these practices despite these mixed outcomes. Whether through creative accounting to reduce taxes or hiring migrants to lower labor costs, FSI executives remain primarily driven by short-term profit maximization to boost company valuations and bonuses. Social responsibility, without visible public recognition, rarely plays a role. And let’s not pretend these hiring practices have anything to do with digital transformation.

Key Factors FSIs Should Consider to Determine If Disruptors Are a Threat

The disruption playbook for fintechs and insurtechs is straightforward. By leveraging superior operating and technology models, startups begin with a more straightforward, low-margin product that isn't a priority for incumbents, creating a business model that traditional players cannot easily replicate. The resulting value proposition becomes so attractive that customers flock to the startup, primarily through word of mouth, making it cheaper to acquire more customers. By focusing on younger segments and scaling in a single combination of product and region, disruptors can expand into less digitally-savvy segments, more geographies, and tangential products.

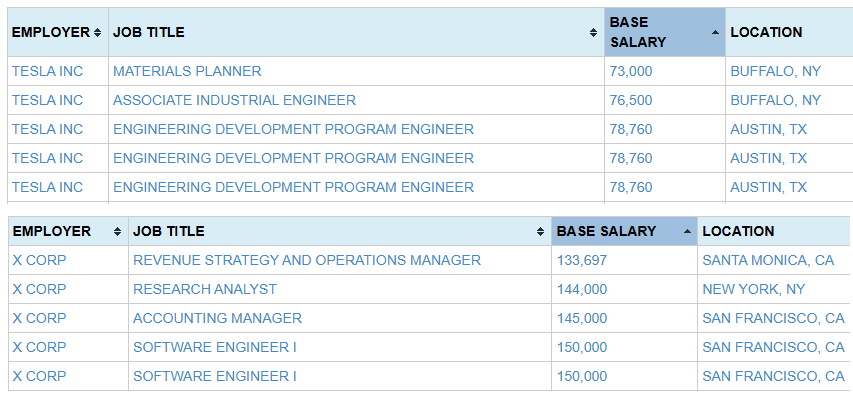

The only difference in developing economies is that the initial product could be more complex and have a higher margin due to less competitive incumbents. For example, two of the most successful global consumer fintechs, Nubank and Tinkoff, started with credit cards in Brazil and Russia, respectively. But the rest of the playbook is essentially the same. Lemonade recently illustrated this roadmap based on facts from its 7-year journey. With 70% of customers under 35, it has already captured 4-7% market share in its initial products:

Lemonade has recently focused on scaling more complex products and expanding internationally. But how will Lemonade win market share against the Progressives and Geicos of the U.S. auto insurance industry? Its unique continuous-telematics technology supposedly allows it to identify over 90% of overcharged customers and undercut incumbents' prices by 15-25%.

“Our Telematics can lower premiums by 15% for ⅔ of customers, and by 25% for ¼”

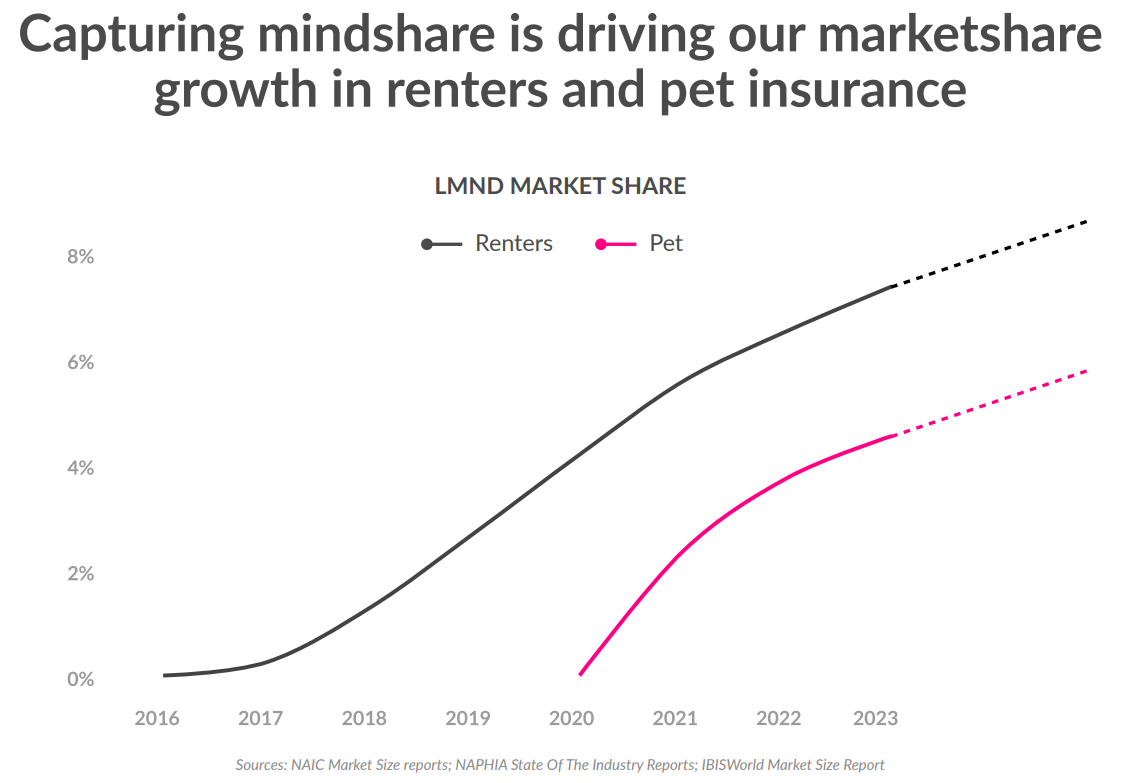

Should traditional FSIs be afraid of such disruptors? The easiest way to gauge this is by assessing whether a disruptor is growing quickly, has positive unit economics, and can offer superior pricing. For example, in the world’s most significant remittance corridor—the U.S. to Mexico—Wise’s fee is half of the incumbents, translating to 1% of the transfer amount. Saving $10 on a $1,000 transfer may not seem like a game-changer for a Mexican migrant to switch providers en masse, but for other ethnic groups, that could be enough to drive a significant shift.

In the case of Lemonade, there is no proof yet that it can consistently beat Progressive and Geico’s pricing by 15-25% for safe drivers. Another simple litmus test for disruption potential is the proportion of new customers acquired through word of mouth. This figure is one-third for Lemonade, compared to 70-80% for leading fintechs like Nubank, Revolut, and Wise.

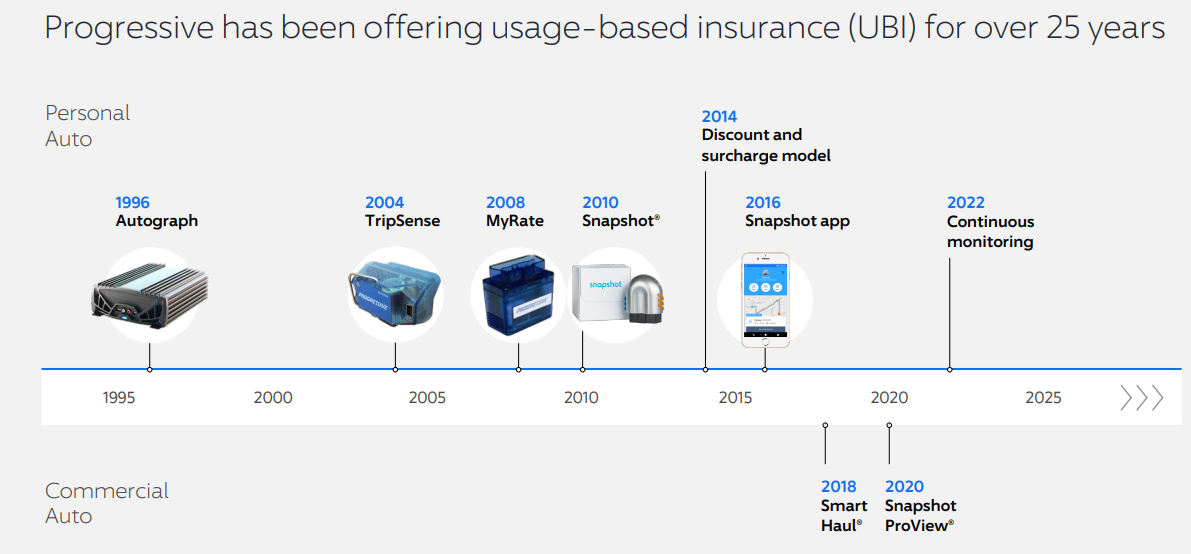

Lemonade's claim of superior continuous telematics is also unclear, as many incumbents have used telematics for years for pricing and claims. For example, Progressive began experimenting with telematics two decades before Lemonade was founded and rolled out continuous monitoring in 2022:

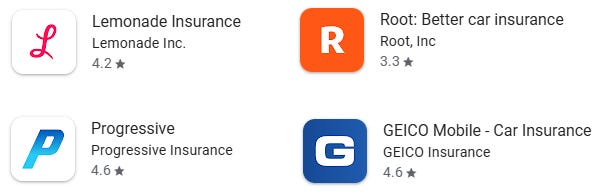

Moreover, traditional FSIs have both more historical data and greater experience with the challenges of the physical world. For example, with skyrocketing claim costs driven by frivolous litigation and fraud in auto insurance, optimizing lawsuit costs by replacing lawyers with AI agents is not an imminent opportunity. Even when it comes to the supposed main advantage of startups—the mobile app UX—traditional carriers don’t appear to be at a significant disadvantage in satisfying their target customers:

If a disruptor builds more impressive digital channels, an FSI should evaluate whether target consumers and businesses rapidly shift their preferences toward a digital-only experience. For some products and regions, as long as sizable consumer and small business segments continue to rely on cash—whether out of habit or to limit government oversight—a hybrid model remains a practical choice, even for fintechs.

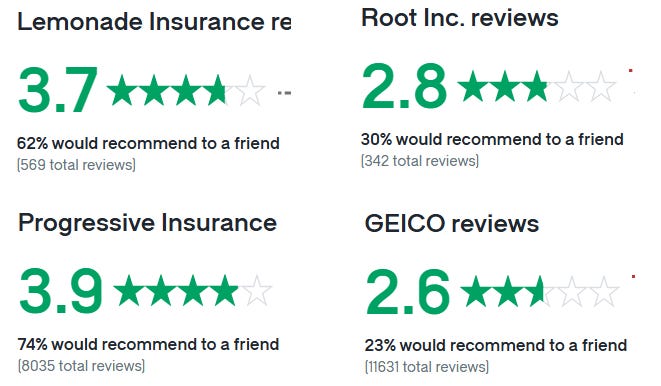

Players like Lemonade may have an advantage if they build a cross-functional operating model where underwriting and claims departments share data and are incentivized to improve unit economics. This aspect of digital transformation would be much more challenging to implement for traditional insurance firms, which are often siloed. However, FSIs can verify on employee review sites whether a leading disruptor has created a uniquely cohesive culture or is facing similar challenges as incumbents:

Without clear differentiation, the 70-90% stock price drop of leading U.S. consumer insurtechs is unsurprising. Their European counterpart, wefox, has even warned twice this year of running out of funds. While disruption looms in some areas of financial services, consumer insurance incumbents have little need to hasten their digital transformation.