One Reason Why So Few Traditional FSIs and Fintechs Escape the Entropy Trap

Also in this issue - Why Fintech Disruption Is More Myth Than Reality: The Uncomfortable Truths Incumbents Already Know

One Reason Why So Few Traditional FSIs and Fintechs Escape the Entropy Trap

A decade ago, USAA Bank was so far ahead of its peers that FSI executives often asked to exclude it from digital benchmarks. Despite using a traditional waterfall approach for digital projects, the bank's military-inspired discipline and cohesion delivered exceptional UX and fostered fiercely loyal customers. However, over the past five years, USAA has struggled financially, facing multiple layoffs and showing no signs of a turnaround:

It’s easy to assume layoffs (aka “restructuring”) are a challenge unique to traditional FSIs like USAA or Citi. However, the past few years have shown that even leading fintechs like Stripe and Block haven’t escaped this fate. The root cause is often bureaucracy sprawl, with explanations like “coordination costs have grown, and operational inefficiencies crept in” or “a vast number of people are slowing us down with structural duplication.”

Smaller fintechs face similar challenges. Stash, a wealthtech, recently underwent a 40% workforce reduction. As often happens with startups, the founders returned as Co-CEOs to navigate the restructuring. One of them recently explained to Fortune the need for “de-layering” to address inefficiencies:

Robinson said the latest restructuring was meant to remove management layers and make Stash “less bureaucratic.” He insisted that Stash hasn’t eliminated any of its products, and that its employees are still working on exactly the same things—just with smaller teams. “We just really wanted to try to remove a lot of the layers and just refocus the company,” he said.

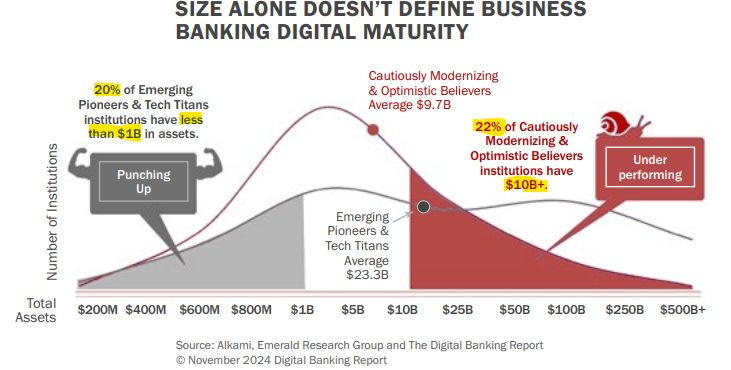

The idea that a smaller size automatically means less bureaucracy is as much a misconception as assuming a larger size guarantees superior digital maturity. Unchecked organizational layering can occur in FSIs of any size and across any product vertical. Similarly, while some larger FSIs lead their peers in deploying advanced digital capabilities, smaller institutions could also excel, as highlighted in a recent report on business banking:

Organizational entropy is a universal force, testing the managerial limits of even the most brilliant industrialists of the 21st century, like Bezos and Musk. I call it the Second Law of Digital Transformation in FSIs: The entropy of an operating model increases over time. Once a company evolves to a more effective operating model, human nature tends to take over, accumulating inefficiencies—hiring excess support staff and creating layers of management to oversee them.

In my conversations, FSI CEOs often categorize their managers 2–3 levels below them into three groups:

10%: Energy generators—those with breakthrough vision and full ownership.

70%: Energy neutral—competent executors of CEO directives but lacking innovation.

20%: Energy drainers—those without novel ideas or adequate execution skills.

The same pattern holds in large fintechs, though with a different distribution, often closer to 50/40/10. Managers in the latter two categories inadvertently push the organization backward, stalling progress and compounding inefficiencies.

Every FSI executive knows by heart what’s needed to combat ongoing entropy: hire talent strong enough to overcome organizational complexity, avoid compromising for social cohesion, align incentives with scalability, and minimize HR’s influence. These principles have been preached since Amazon’s early days, and nothing fundamentally new has emerged in over a decade.

However, the hardest change is personal. Each FSI executive must be a part-time doer. If they don’t lead by example, who else will empower less driven employees to strengthen their operating muscles—an Agile coach?

Even in a typical fintech, many FSI executives either lack interest in hands-on involvement or are unsure where to begin. This often necessitates founders stepping back in to reset the organization. These resets tend to deliver impressive short-term results. For instance, Brex, a business cash management fintech, recently achieved triple revenue growth and an 11-point NPS improvement while reducing expenditures by 70%. Its founder and CEO, Pedro Franceschi, sharpened the focus on product releases, removed two layers of management, and eliminated roles dedicated solely to people management and organizational building:

“During the first 6 years of Brex, things just “happened.” We pioneered the category, and had instant product-market fit — scaling from 0 to $100MM ARR in 16 months, despite mistakes on the product, GTM, and hiring. This stopped being true in 2023, and it required a painful reset to bring our culture back into what it once was: a culture of builders, willing to go extra hard to serve customers and build a generational company over the next decade.”

If your FSI aims to perform at a fintech-grade level, would half of the executives be enthusiastic about spending a few hours each month working directly with frontline teams? Or would they rather stick to the cycle of periodic layoffs and de-layering?

Why Fintech Disruption Is More Myth Than Reality: The Uncomfortable Truths Incumbents Already Know

The idea of disrupting financial services and insurance has rested on three key beliefs: 1) the arrival of a game-changing invention (smartphones, AI, blockchain, etc.), 2) incumbents’ failure to adapt quickly, and 3) fintechs scaling the invention to offer better value and capture market share. This vision has mostly fallen short, particularly in risk-based products. For example, consumer insurance remains essentially unchanged, with incumbents holding 40-90% market share and continuing to grow steadily in revenue and profit.

Over the past 15 years, fintechs and insurtechs have learned that proprietary data—not novel technology—is the true differentiator in risk-based products, while UX innovations are relatively easy for incumbents to replicate. Another challenge to the disruption narrative has been the brutal competitiveness of certain products. Disrupting an industry that operates on razor-thin margins or persistent losses is inherently difficult. While consumer insurance is widely recognized for its lean or unprofitable nature, commercial insurance isn't much better off:

In risk-based verticals, incumbents gain another edge from their larger datasets: combating the biggest downside of digital products—fraud. While rapid sign-up growth sounds great, fintechs often discover that a significant portion is attempting fraud. The lack of friction, once seen as a no-brainer, also has a downside regarding retention. Recent research shows that as banks and neobanks improve customers' ability to move money, they paradoxically retain fewer deposits:

… if all deposit transfers are expected to be processed the next business day, the demand for low-interest, precautionary, and transactional deposits would decrease by approximately 30%, while related deposit transfer flows would increase by 40% as depositors become more active.

Even in seemingly simpler products like payments, incumbents have maintained dominance by closing the innovation gap. JPMorgan Chase remains one of the leading global processors, handling nearly half of all e-commerce transactions in the U.S. As tech firms scale existing talent with novel tools, top traditional FSIs have stepped in, recruiting 20% of technology graduates from the best U.S. programs. This shift aligns with FSIs' growing focus on differentiating through in-house digital product development. JPMorgan now employs 50,000 technologists, and its merchant processing software has significantly evolved from this 19th-century beauty:

Another surprising shift from common wisdom a decade ago is that, in some FSI verticals, clients and employees still don’t view technology as a key differentiator. For instance, digital transformation in wealth management is so overrated that it made perfect sense for Citizens to first hire 250 expensive relationship managers before even considering upgrading systems and technology to support them. Citizens Financial Group Inc. CEO Bruce Van Saun recently described this approach to Bloomberg:

Now that the bankers are at Citizens, the company is focused on improving its systems and technology to better serve former First Republic customers.

“We brought the people on board, and now we have to build up the technology and the operating frameworks to delight the customer the way they were delighted” at First Republic, Van Saun said.

Disruption is challenging when the target segment values hand-holding over pricing and digital UX, as seen in wealth management. However, even in seemingly price-sensitive sectors like remittances, consumers—including the younger generation—stop prioritizing costs beyond certain reasonable thresholds. In a recent competitor analysis, Wise identified Remitly as having the highest FX markup among non-banks. Yet, Remitly generates the most digital revenue in the global consumer cross-border space and is the fastest-growing among top players.

Due to the abovementioned factors, no game-changing value propositions are strong enough to compel consumers or businesses to switch from their incumbent FSI to a fintech en masse. Moreover, when such products do emerge, they often prove unsustainable. For example, when Atlantic Money launched cross-border consumer transfers in 2022, its tiny fee led to unprecedented growth in transfer volumes. However, the business model was questionable, and its sustainability will remain unknown after the recent sale.

The most innovative credit card in history, Bilt, appeared to have figured out how to give consumers points for rent payments with no fees. That was until the Wall Street Journal discovered that the issuing bank, Wells Fargo, lost $10 million monthly due to a poorly structured deal. Behind-the-scenes discussions recently spilled into the public when, in the annual letter to Bilt members, the company's founder downplayed Wells Fargo's contribution and even blamed the bank for the issues:

“We also hear the challenges many of you have had with approval rates, credit line sizes, and the need for core tech features like authorized users, pay over time, and auto-pay integrations. Some of you have mentioned that your credit limits are too low to cover more than a month or two of rent, leaving little room to take full advantage of the card’s benefits – especially considering the average FICO for these members is above 750. We hear you loud and clear. These are all things that require support from our issuing bank partner, and we're actively working on solutions.”

With every innovation, the hope of disruption resurfaces. Fintech experts, VCs, and some FSI executives believe that consumers and businesses will adopt novel technologies once they try them. The latest potential game-changer is stablecoins, already used in some countries for securities and collateralization. However, for payments and transfers, stablecoins may be the only financial product in history without a repeat user base while being frequently associated with criminal activity:

The network [of Russian criminal enterprises] has been using Tether as its crypto currency “almost exclusively”, replacing Bitcoin as the “crypto currency du jour”, said Lyne [NCA’s Head of Cyber Intelligence]. Tether is designed to keep a fixed exchange rate with the dollar and perceived by those involved in the illicit transfers as less risky than other crypto currencies.

The good news for disruption believers is that they will be vindicated, albeit partially and in the long term. Not all incumbents will succeed in closing the innovation gap with top fintechs, so rather than disrupting incumbents, we are more likely to see a combination of traditional FSIs and fintechs winning market share from laggards. Overall, novel technologies improve our financial lives and will hopefully make life more difficult for criminals.