Scalability of Cost Centers in FSIs: The Exception of Financial Crimes

Also in this issue: FSIs Should Resist Kitchen-Sink Innovation and Return to Basics

Scalability of Cost Centers in FSIs: The Exception of Financial Crimes

“Your abhorrent view is beyond insulting to every one of our 4,000 FinCrime fighters who work tirelessly every minute of every day to build trust, protect customers' funds, combat and report criminals, all while maintaining higher than minimum compliance standards across a complex global AML and fraud regime,” responded Revolut’s head of Financial Crimes for APAC, Nelson Yiannakou, to my LinkedIn post. I suggested that banks and fintechs stage a theater with excessive manual labor to placate regulators, using the story about how Revolut got the UK banking license as an illustration.

“4,000 FinCrime fighters” represents almost 40% of Revolut’s headcount, and yet Nelson didn’t see anything shocking about that. This might be an expected reaction from the head of HR in a traditional FSI or perhaps even their head of function, but hearing this from a Revolut executive was surprising. After all, Revolut is notorious among leading fintechs for its tough “never settle” culture, where everyone acts as an owner and questions everything to drive scale.

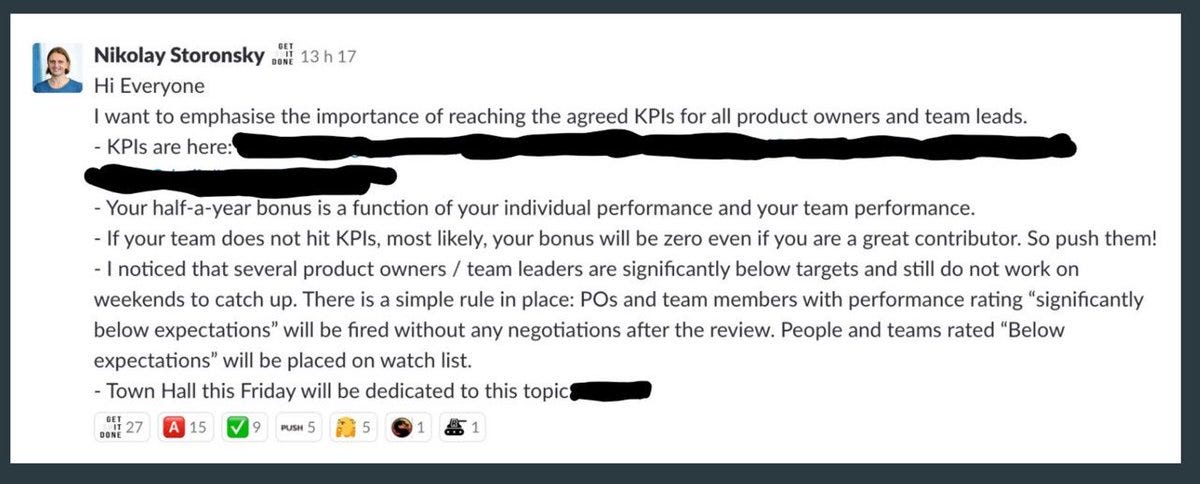

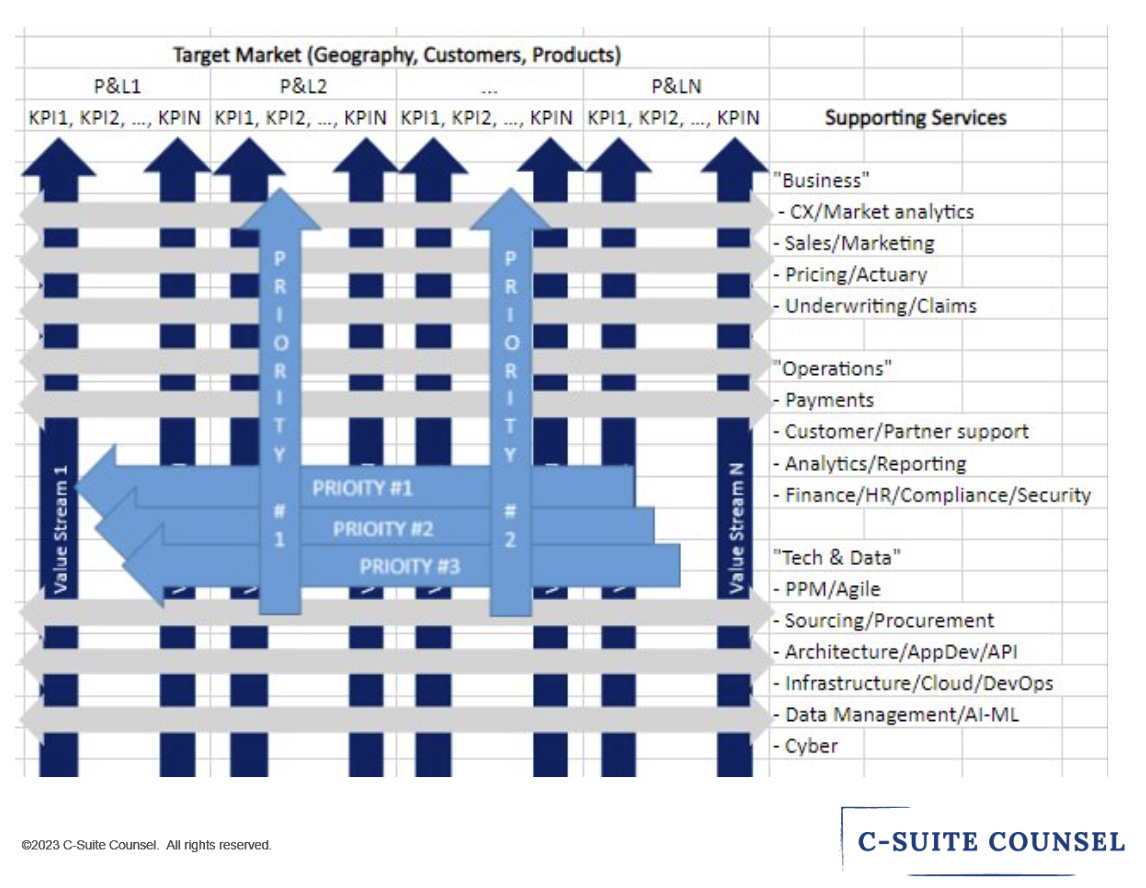

In Revolut’s culture, Nelson must hit his KPIs, but are those related to scaling? That seems like a silly question. Revolut operates within a target state model where supporting services like Financial Crimes focus on two North Star metrics: higher satisfaction of the profit-generating units they support and increasing scale in providing that support. Revolut also understands that traditional executives in charge of support services instinctively hire staff and launch initiatives rather than doing the work themselves, thus diminishing scale. After Revolut made the mistake of hiring too many such executives into HR in 2020, they were quickly fired.

It should be natural for Revolut to report its Financial Crime progress with fewer employees per crime incident while the crime rate per customer or transaction declines. The fintech could also demonstrate higher effectiveness by reporting fewer SARs dismissed after ATL testing or fewer misses in BTL testing. This would suggest that Revolut wouldn’t need such an unprecedented ratio of Financial Crime staff to the rest of the organization going forward.

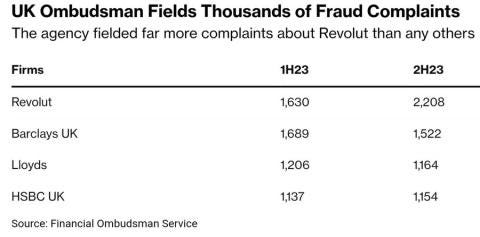

However, Revolut isn’t publishing reports with such information, and regulators are to blame. To get a banking license, Revolut had to demonstrate that it takes financial crimes seriously. For regulators, this doesn’t mean a decrease in the rate of fraud or money laundering. For example, Revolut customers' complaints about fraud are the highest among consumer banks in the UK and keep growing in line with revenues. Yet, last week, Revolut received its UK banking license.

Since only about 0.02-0.03% of its customers complain about fraud to authorities, why couldn’t Revolut get its banking license a year ago? Because regulators tend to look at the process rather than the outcomes. Revolut’s emphasis on automation would have made it harder to assess its compliance, as described in a recent Financial Times article:

“Nik had this vision that compliance would not be manual with people sat on desks looking through transactions and manually blocking accounts,” said a former senior employee. “He really invested heavily on the technology side of compliance and that just doesn’t sit well with regulators.

“Revolut had to go away from that . . . they had to hire all those people, build all those processes, bring all these bankers in.”

Giving up on the maximized digitization vision for this function and eager to obtain the license, Revolut had to start publicizing the massive increase in Financial Crime staff as if they were bringing in the world’s leading Generative AI experts:

At least Revolut, with its profitable products like net interest margins on deposits or crypto trading, can afford such heavy staffing in Financial Crimes. Traditional FSIs and fintechs with leaner margins are choosing to derisk from heavily regulated segments altogether. For example, B2B neobank Mercury recently had to terminate clients with beneficial owners residing in Ukraine, Nigeria, and a few other countries because they consumed over 50% of compliance/risk capacity while representing less than 1% of deposits. In response to the backlash, especially regarding war-torn Ukraine, Mercury’s Founder and CEO, Immad Akhund, had to explain:

“To give more context: the number of customers in these countries is very small (<1% of Mercury deposits), but it was putting a lot of strain on our operational teams and all of our financial partners (partner banks, treasury, payments, etc). We’ve seen the regulatory environment become stricter recently, which has made us change our approach to certain situations.”

While traditional FSIs should ultimately target infinite scale with zero employees for other cost centers, regulators continue to be the ultimate guide for the balance of automation versus human staff in Financial Crimes. Let’s just hope that we won’t see leading FSIs and fintechs having over 50% of employees working in Financial Crimes in our lifetimes.

FSIs Should Resist Kitchen-Sink Innovation and Return to Basics

AI has been one of the more popular digital investments in financial services and insurance for a decade. Specifically, machine learning has proven to be a powerful tool for fraud detection, underwriting, and customer support, in areas characterized by rich structured data and a wide range of employee performance. However, these self-evident constraints seemed too restrictive for such groundbreaking technology, so AI was elevated to an enterprise-wide priority.

Rather than empowering business lines and functions to drive AI initiatives, many large FSIs decided to establish an enterprise-level AI team. They would start with about 10 people, quickly growing to 50, and it was not unusual to see 100+ enterprise AI teams by the time ChatGPT arrived in late 2022.

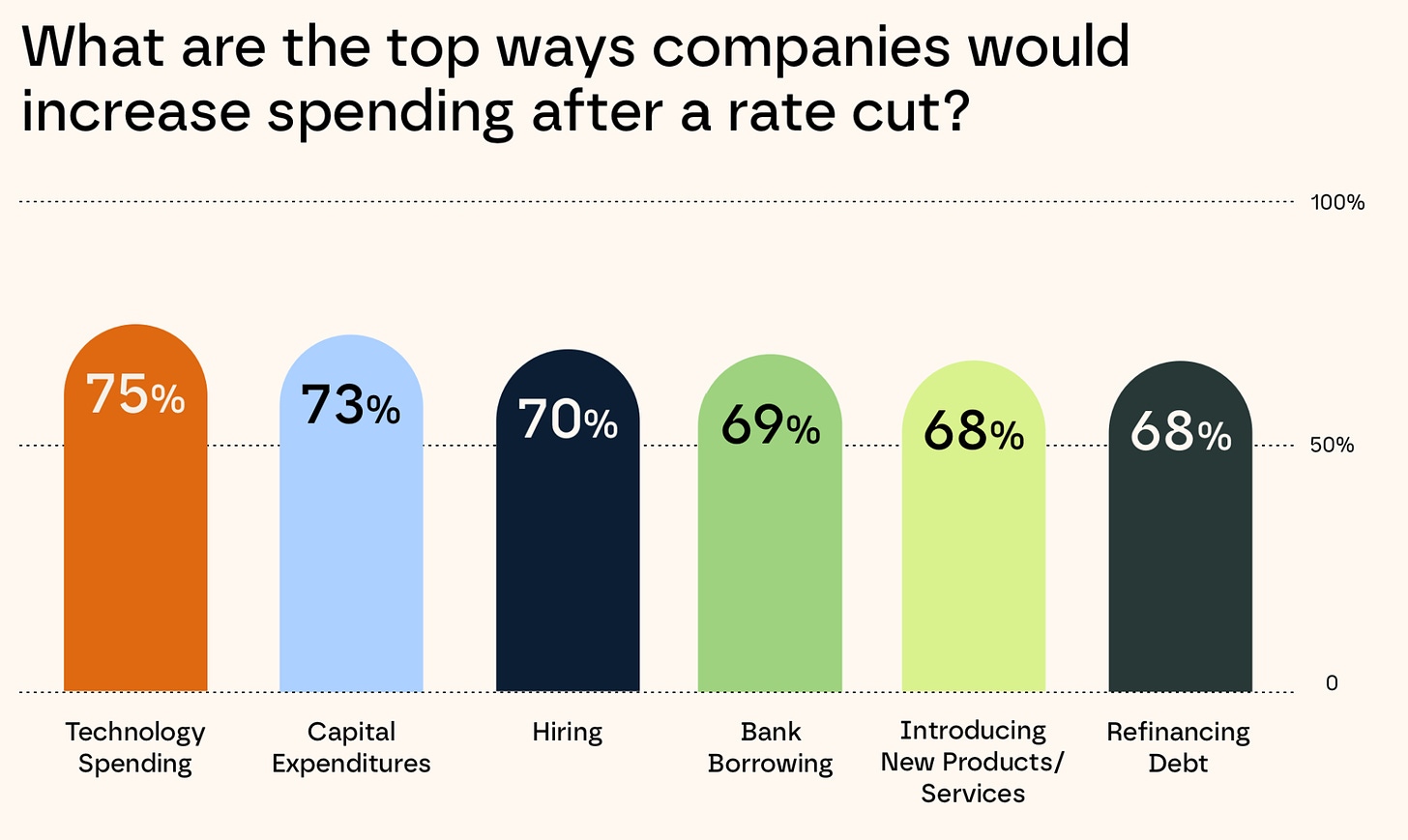

This coincided with a seminal shift in how FSIs view technology. Thanks to the tireless efforts of vendors, consultants, and analysts, even CFOs now consider technology spending as mandatory and the best use of funds. A recent survey of U.S. CFOs by Bloomberg and PNC revealed that technology would be their top spending area following a rate cut:

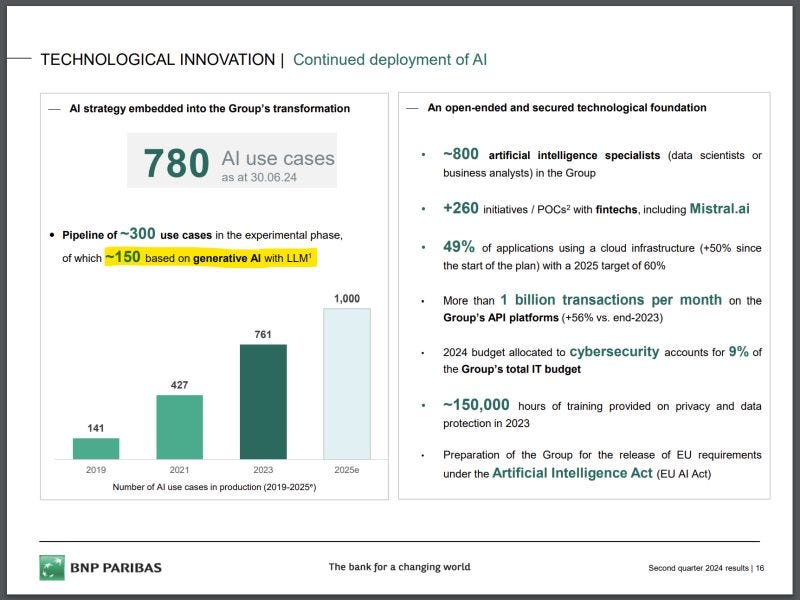

Generative AI hype only exacerbated that trend, with some large FSIs, like BNP Paribas, bragging in investor presentations about piloting 100+ GenAI use cases with hundreds of AI specialists:

This is contrary to the tenet of Agile, one of the five critical pillars of digital transformation. Given the unprecedented cost and difficulty of scaling GenAI, the best course of action would be to assign minimal cross-functional teams of the best resources to a few of the most lucrative use cases, then scale or pivot them before pursuing additional ones.

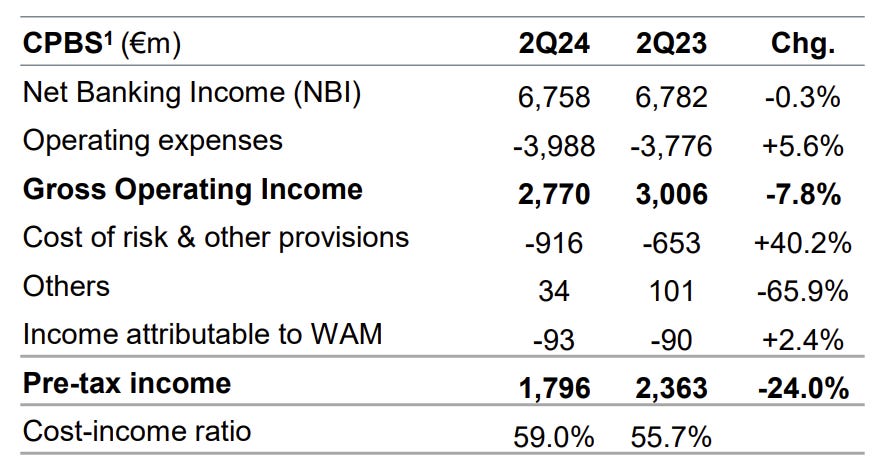

Instead, with a kitchen-sink approach to GenAI, FSIs are spreading both their best talent and leadership attention too thin while wasting funds on use cases that lack quality data and/or differentiation in performance. Hence, it is not surprising that such feverish activities have had no impact on BNP Paribas's most relevant division, CPBS (Commercial & Personal Banking and Specialized Businesses). In the past year, both its gross operating income and efficiency ratio have materially worsened:

But it’s not just company funds that suffer. The ubiquitous top-down innovation in traditional FSIs has created a major chasm between the expectations of the C-Suite and the experiences of employees. A recent study by Upwork highlighted a universal exuberance among leaders about AI's impact on productivity versus the frustration and confusion experienced by their reports:

Despite 96% of C-suite leaders expressing high expectations that AI will enhance productivity, 77% of employees using AI say these tools have added to their workload, and nearly half (47%) of employees using AI report they do not know how to achieve the expected productivity gains.

Customers are also affected by such an un-agile approach. My financial services and insurance providers now frequently prompt me to review account insights. Similar to the proliferation of internal reports, executives in these FSIs genuinely believe that more information of any kind is helpful. While exalting user-centricity at conferences, many of them would never consider asking customers or employees which data insights would be most useful. As a result, most of those AI-generated dashboards are useless at best and confusing at worst:

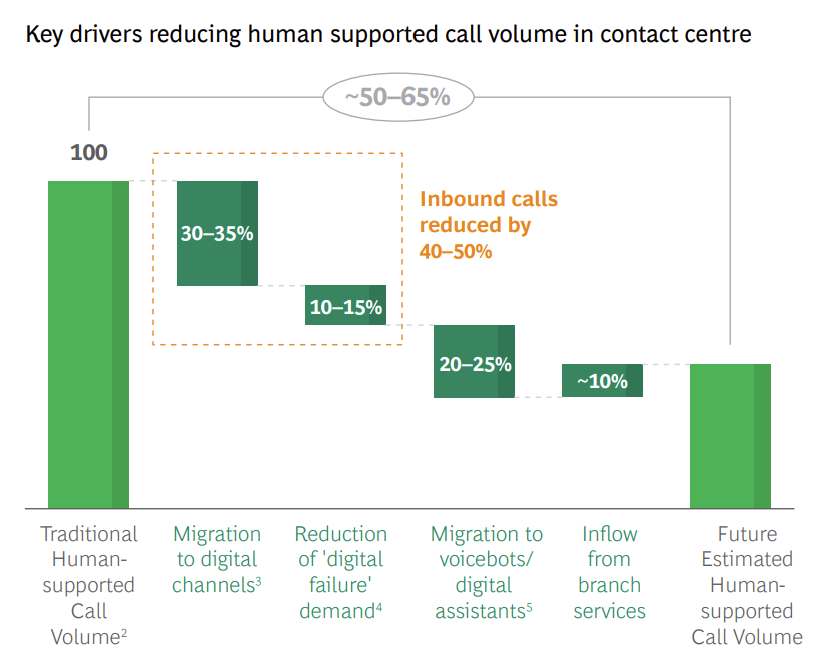

Even in areas where digitization seems most applicable, capturing benefits is often much harder than it appears. A recent BCG report outlined the familiar drivers for staff reduction in one of the most popular areas: contact centers. As a decade ago, banks are expected to cut half of their staff by enabling digital self-service, scaling digital assistants, and reducing UX errors:

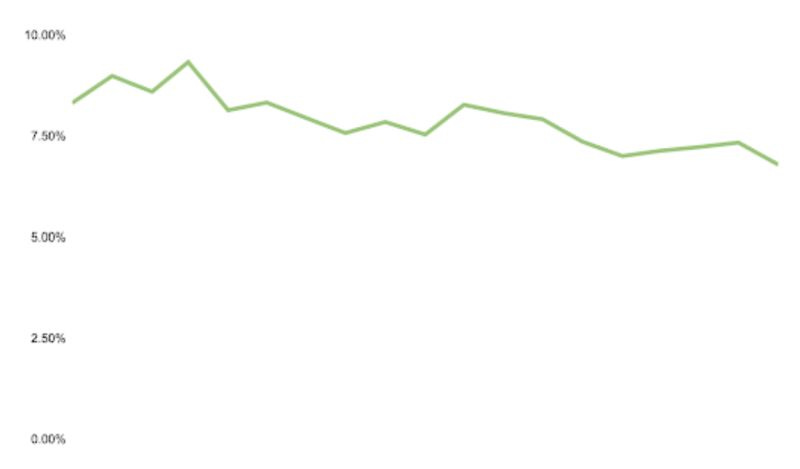

Unfortunately, in 2024, there are no longer any low-hanging fruits. The days of password resets or money transfers being done manually are long gone. Today’s customers reach out to FSIs because they strongly prefer human connection or have much more complex questions that often lack immediate scalable solutions. Even for the most advanced fintechs like Wise, it has taken years to significantly reduce customer contact rates, with periodic spikes along the way:

Wise is achieving this not through technological innovation per se but by meticulously eliminating underlying root causes with superior UX:

Significantly reducing reliance on SMS for authentication

Allowing customers to make some verification changes independently and better understand rejection reasons

Speeding up money transfers to meet customer expectations.

The good news for traditional FSIs is that leading fintechs like Wise are not driving scale with some secret groundbreaking operating model. The most effective organizational designs and cross-functional playbooks have been established for over a decade. FSI executives have heard about these best practices for years and just need the courage to step off the innovation hamster wheel and return to basics.

Such resets are even required for top fintechs like Block. As part of a year-long unclogging, its founder, Jack Dorsey, took back the reins to eliminate bureaucratic barnacles and bring the fintech back to its roots:

“We’re going to reorganize our entire company by function and disband our business unit reporting structure,” Dorsey said in the note which was viewed by Fortune, adding that the move would take Block back “to how we started as a company.” The subject line of the note was “fn block.”

In the next leadership meeting, start by reminding the head of data that the scaling of their AI capabilities is measured by generated profit, not the number of pilots. It would also be helpful if CFOs remembered that their job is to instill such discipline rather than being technology cheerleaders.

![strip/2020-12-31 ] - Dilbert - Quora strip/2020-12-31 ] - Dilbert - Quora](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb3f01cca-dc6c-4617-968e-5ea466821954_403x125.jpeg)