Why Couldn't Traditional FSIs Launch the Billion-Dollar Products Fintechs Are Now Offering?

Also in this issue: Following Hype Makes FSIs Look Cool Short-Term but Costs Them Long-Term

Why Couldn't Traditional FSIs Launch the Billion-Dollar Products Fintechs Are Now Offering?

Remitly was launched in the US when Western Union and Xoom were already generating more than $100 million in digital revenue and growing at over 20%. Remitly now generates more than $1 billion in revenue, growing at over 30%. BNPL was initially considered a low-brow product mainly suited for the developing world, which created an opening for Affirm in 2012. It is now approaching 20 million active customers and $3 billion in annualized revenue, still growing at around 50%. Coinbase generates more than $5 billion in revenue, with growth over 100%.

In the last 15 years, numerous consumer fintechs have surpassed $1 billion in revenue, often generating market values 10 times higher. Why didn't top traditional FSIs launch similar products back in 2010? The simplistic answer is that they are costly, bureaucratic behemoths incapable of launching and scaling disruptive solutions. However, the reality is often more nuanced.

Ignorance is bliss

On a recent Deciphered podcast, the Director of Research at Fidelity's Digital Assets said that cross-border transfers haven’t changed much since the 1970s, and nobody laughed at him. Such ignorance is common not only among supposed crypto experts but also among the operators themselves. When launching Coinbase in 2012, its co-founder and CEO, Brian Armstrong, believed that merchants would switch to crypto payments from accepting credit cards due to their high costs:

“Credit card fees are too high. In the next five years merchants are going to start moving away from paying 2.5% plus 30 cents per transaction when fast secure alternatives become available. They're going to (at first) offer them at checkout alongside traditional credit card options, and then eventually start incentivising consumers to make the switch. If Amazon has a 5% margin on a $100 text book they aren't going to give $2.00 of their $5 to Visa/MC forever.”

That never happened. The use of crypto in regular payments remains tiny and is not increasing, as illustrated by the Bank of Canada’s annual survey of weekly payment habits:

That, of course, isn't stopping Brian, twelve years later, from continuing to pretend that Coinbase is addressing pain points in domestic payments and cross-border money transfers while serving its core market—young men with more money and free time than they know what to do with, so they trade crypto. Consumers don’t just spend a trillion dollars on junk food, tobacco, or alcohol each year; they also spend a trillion annually on gambling bets in the US alone. Coinbase satisfies that type of craving.

The brilliance of crypto leaders like Coinbase is that ignorance of fiat payments and transfers hasn’t hindered their success—in fact, it might have even been an advantage. Building a large-scale electronic exchange of widgets can be lucrative on its own, regardless of the function of those widgets, to the tune of a $50 billion market cap.

Regulatory arbitrage

In a stroke of serendipity, the Durbin Amendment passed in 2010, right as the second fintech wave was about to begin. This legislation allowed small banks to continue charging high interchange fees for debit card transactions while capping those fees for larger banks.

This created a lucrative niche for neobanks, which could partner with small banks to offer consumers better value propositions, earning significantly more on debit card transactions than larger banks. A decade later, most well-known neobanks like Chime, Varo, and Dave still generate 70-80% of their revenue from this regulatory loophole.

Excessive risk

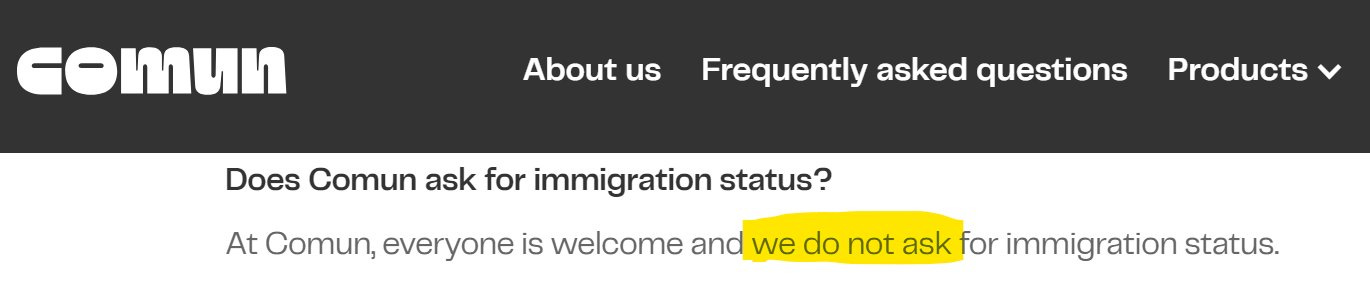

Comun is a US neobank targeting Latin American migrants, particularly those without valid visa status. Although opening bank accounts for individuals in the country illegally isn't explicitly prohibited, it does involve considerable risks. However, with more than 2 million illegal crossings each year, this consumer segment appears highly lucrative. Comun taps into this market by not inquiring about immigration status or sharing such information with the US government.

Regulations do require verifying that a person is physically in the US, but Comun offers an option to verify an address via the geolocation of a cell phone rather than only through official documents.

Despite the obvious risks that might scare traditional FSIs, investors have been enthusiastic about Comun’s business model. It recently raised $21.5 million, less than nine months after a previous $4.5 million raise. Ironically, among its open roles, Comun is currently seeking a Head of Compliance:

Another example of excessive risk in financial services is business models with unit economics that are so tiny or non-existent that their sustainability relies on hopes for a quick acquisition or becoming a market leader.

Similar to Facebook acquiring WhatsApp for $19 billion without revenue, fintechs could be acquired even if they don’t charge for their services. For instance, Braintree acquired Venmo in 2012 for $26.2 million.

Bilt’s credit card is costing Wells Fargo millions in monthly losses, and Atlantic Money makes virtually nothing on its cross-border transactions. However, if these solutions gain top market share in their respective categories, they might eventually break even.

Gray zone

Maybe not for timid traditional FSIs, but pushing the legal envelope is exciting for more adventurous types. Even among consumers, there is always a segment that re-discovers scams like check fraud, hoping to cash out from bank money they don’t have. Hey, if retailers allow you to walk out without paying for merchandise, maybe banks would do the same?

Fintechs have also been seeking similar edges, or "growth hacking." In its early days, PayPal was notorious for operating in a gray zone, such as inserting its payment widget into eBay listings without agreement and being sued by state regulators for offering bank-like services without a license.

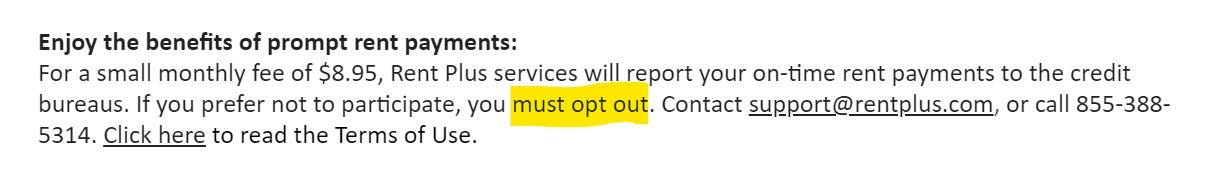

Some fintechs engage in growth hacking by imposing fees for services like credit building. A leading expert on the topic, Alex Johnson often says, 'All credit building services should be free, opt-in, and report both positive and negative data.' But fintechs like Rent Plus automatically enroll tenants in a monthly $8.95 payment, requiring them to opt out:

Crypto fintechs have expanded the gray zone, with FTX and Binance's legal troubles making news in recent years. However, many have avoided jail and continue operating by paying periodic fines. In 2015, Abra raised $12 million to offer remittances via Bitcoin while claiming it didn’t need money transfer licenses because it was a technology company. Ripple's market cap is over $30 billion, as it promises that its coin (XRP) will revolutionize the cross-border payments industry. In 12 years, has Ripple disclosed any entities that pay for its services or revealed the overall revenue generated from such paying clients?

Even within crypto, there are different levels of “gray.” While traditional crypto has failed to achieve financial inclusion for some of the most marginalized entities, stablecoins like Tether have successfully closed the wealth gap by helping sanctioned countries maintain global trade. Tether’s market cap alone is now $120 billion, demonstrating that its adventurous spirit in operating in the gray zone is well rewarded.

What should traditional FSIs do?

Looking at all these exciting opportunities, should traditional FSIs have selectively pursued any of them? No. What might be forgiven or overlooked by regulators, courts, and media with fintechs will become a bull’s-eye for established institutions.

Some large banks in the US are learning this the hard way. In the last decade, they discovered a lucrative customer segment: Chinese students (not US residents) depositing billions in cash each month. Free liquidity is always nice unless the downside involves potentially laundering fentanyl/meth proceeds from a triad-cartel partnership. That could become quite costly:

Instead, traditional FSIs should continue targeting use cases with no regulatory uncertainty, avoiding those that enable addictive consumer habits or seem too good to be true. The edge will be found not in cutting corners but in rapidly enhancing digital operating muscles to outcompete both traditional peers and fintechs in unit economics and top-line growth.

Following Hype Makes FSIs Look Cool Short-Term but Costs Them Long-Term

The beauty of a large traditional financial services firm lies in its sustainable, profitable business model. While fintechs like Wise or Mercury meticulously manage their costs to compensate for low pricing, large FSIs can afford to spend vast sums of money, hoping for the best. Inquiring with the head of any cost center—such as IT, Compliance, or HR—about which of the products is the most profitable or their cost contribution on a per-transaction basis often reveals that no one has asked them such questions before.

This relaxed attitude has been a gold mine for consultants and research firms, who profit from FSIs through periodic cycles of outsourcing and insourcing, repeating every decade or so depending on what's popular (we are currently in the insourcing phase). Another enduring seesaw is the shift between giving more autonomy to business lines to drive effectiveness and then reclaiming that power at the enterprise level to drive efficiency.

Technology hype

In the past decade, FSIs have experienced additional technology-specific hype cycles. The most prominent has been cloud migration, followed by cloud repatriation. With public cloud costs continuing to soar and security concerns rising, many CIOs are now planning to move workloads back to private clouds and on-premise solutions:

A big reason for the yo-yo approach to cloud usage is the underlying AI hype. Many FSIs jumped into numerous GenAI pilots starting in 2023 and are now transitioning to multiple production environments without comparing TCO (total cost of ownership) against realistic benefits. Instead, ballooning costs are justified by unrealistic expectations of cost cuts due to productivity gains.

Some of the most cited examples come from Klrana. In February, the global fintech announced that its AI tools performed the equivalent work of 700 full-time agents. When asked about the timing of upcoming layoffs, Klarna explained that it was merely trying to spark a global conversation about the impact of AI. Despite this clarification, the original news went viral, and Klarna has recently doubled down with an even wilder claim, as reported by the BBC:

The buy now, pay later firm Klarna is seeking to get rid of almost half its employees in the coming years through efficiencies it says arise out of its investment in artificial intelligence (AI).

The firm has already cut its workforce from 5,000 to 3,800 in the past year, and wants to reduce that to 2,000 employees by using AI in marketing and customer service.

Incredible—so Klarna has already laid off more than 20% of its employees and plans to lay off the same amount in the coming years, all while growing nearly 30% annually?! Of course not. Klarna had to clarify again that no layoffs have occurred and none are forthcoming:

Klarna told UKTN that no layoffs have taken place, nor will take place as part of the company’s emphasis on the role of AI.

On the company website, the number of employees is still listed as above 5,000:

UPDATE SEPTEMBER 5, 2024: Following the newsletter's publication, Klarna coincidentally updated its website to reflect the reduced employee headcount. While the staff cuts are real, Klarna has avoided explicitly attributing them to AI in interviews, even as it highlights AI’s role in performing manual work in its press releases.

Instead, Klarna inadvertently explained with the headline “The Revolutionary Impact of AI” that the fintech had finally figured out how to avoid keeping customers on hold for 11 minutes:

In the first half of 2024, we saw firsthand the benefits of adopting practical AI. We also made a conscious decision to address the societal impacts of generative AI. Our AI assistant now performs the work of 700 employees, reducing the average resolution time from 11 minutes to just 2, while maintaining the same customer satisfaction scores as human agents.

If your bank doesn’t keep small business clients on hold for 11 minutes, GenAI might not be such a game-changer for you.

Disruption hype

As Klarna gears up for its IPO, amplifying technology hype is insufficient. In a recent interview with Yahoo Finance, Klarna Co-Founder and CEO Sebastian Siemiatkowski expressed eagerness to disrupt US retail banking. Guess which pain point Klarna plans to exploit to drive consumer adoption? Americans paying "substantially higher payment fees:"

It already seems odd that Klarna is focused on disrupting the world’s most competitive retail banking market before addressing its home turf in Sweden, especially since its revenues there have declined this year. But feast your eyes on Klarna’s UX, which aims to disrupt Chase and Bank of America. It was apparently inspired by Google Search’s clean design in taking on Yahoo and AltaVista’s search engines a quarter-century ago:

Of course, some traditional banks might take such claims seriously and decide to go on the offensive, setting up digital banks in other regions to disrupt those markets. Chase has learned exactly how much it costs to be indistinguishable from the best neobanks in the UK regarding service quality and digital features: $0.5 billion in losses in 2022 and $1 billion in 2023.

Believing in disruption hype has been very costly for startups as well. In the US consumer P&C insurance market, none of the leading insurtechs are yet profitable. A decade ago, they aimed to disrupt behemoths like Progressive—companies that few mainstream experts fully understood were so cutthroat. As a result, the stock prices of these insurtechs remain 90-95% below their highs, and some even take pride in pausing core products:

Identity hype

The identity of consumers has been increasingly emphasized for targeting by both traditional FSIs and fintechs in recent years. The premise is that a person’s age, sex, or skin color makes them fundamentally different due to psychological factors or historical marginalization.

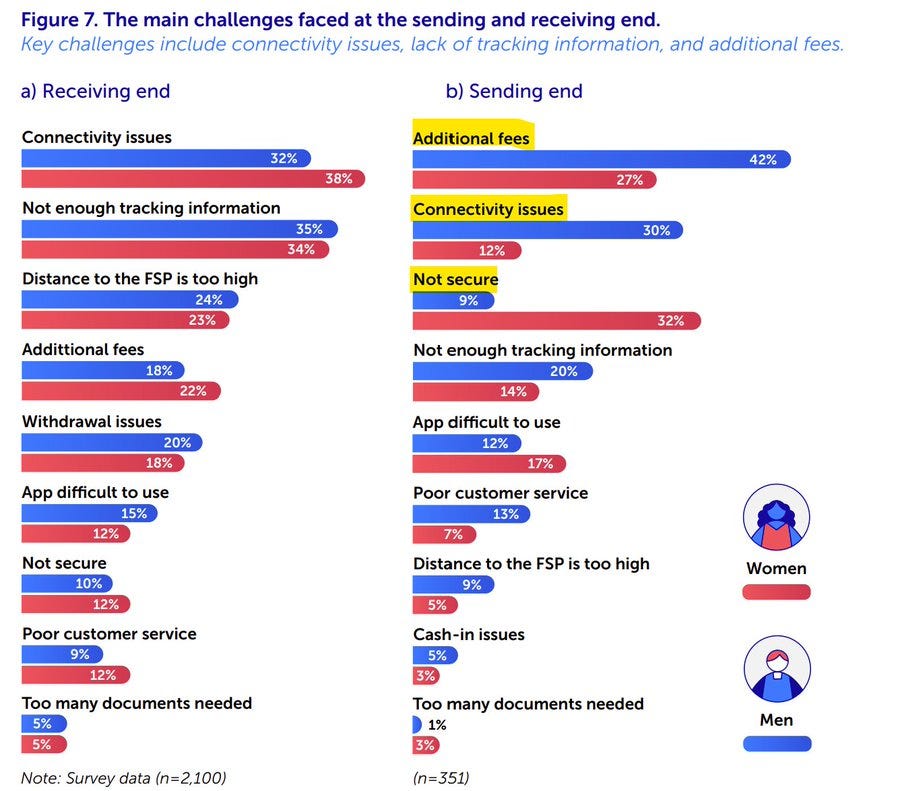

Indeed, there are material behavioral differences across sexes and ethnicities in some FSI products. For example, in cross-border money transfers, Indians living abroad are among the most price-sensitive segments, so many providers charge lower prices for them compared to other nationalities. Women tend to be more cautious and concerned about security, while men focus more on pricing and tech features, leading some providers to emphasize different aspects of their value propositions in marketing.

However, FSIs and fintechs make a costly mistake when they embrace identity hype by launching fundamentally different products for specific groups. For example, over the past several years, it became common to believe that younger generations require a completely different value proposition. The assumption was that they were too online, traumatized, and financially constrained to use the same products as older generations. In reality, Gen Z is not only set to inherit massive wealth but is also emerging as the most financially literate generation:

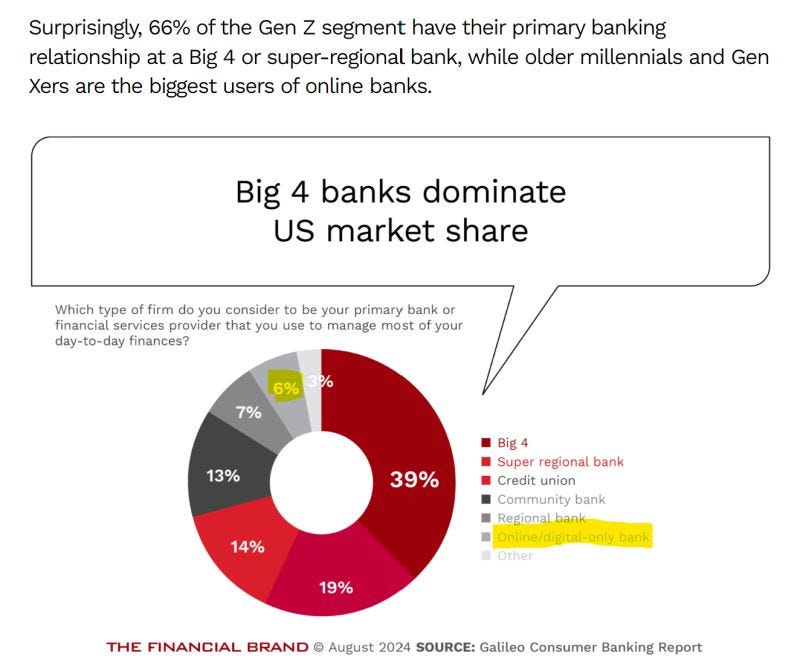

Even more surprisingly, Gen Zers are more likely to bank with traditional large banks rather than fintechs, compared to older generations:

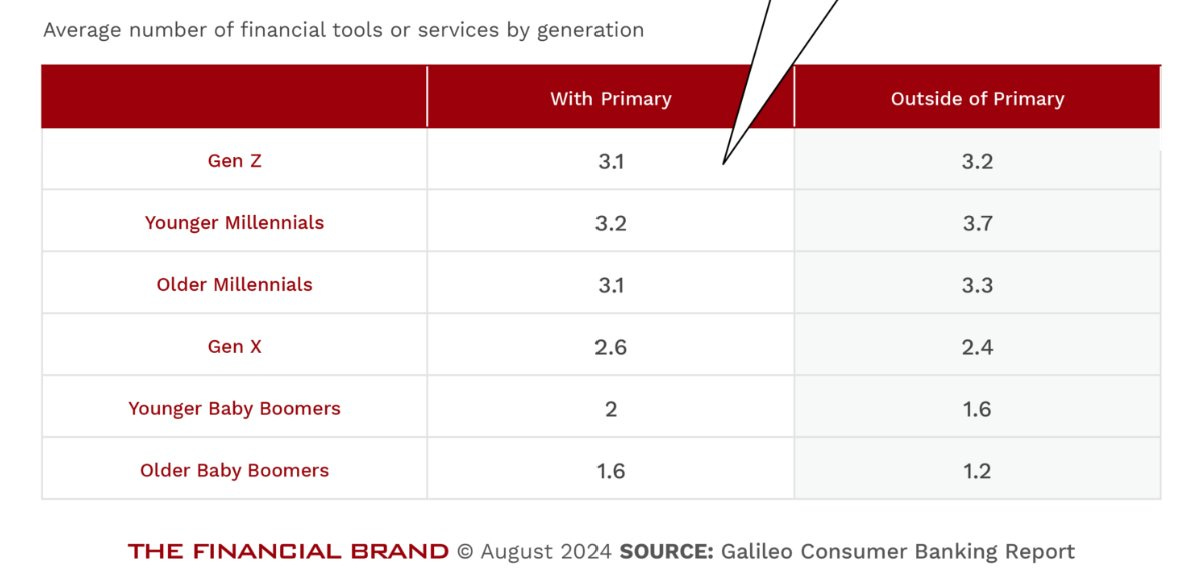

The main difference with Gen Zers is that they typically have one more financial app on their phones, often for P2P money transfers. Since products like Venmo are still struggling with monetization, this should not warrant a complete change in targeting strategy for this segment.

Across all FSI products, younger consumers don't live up to the hype of having unique preferences. Instead, like everyone else, they view financial services and insurance as necessities without craving more digital features or engagement, as evidenced by the ubiquitous popularity of set-it-and-forget-it target-date investment funds:

In conclusion

As Kamala Harris likes to remind us every few months, traditional FSIs should play to their strengths, returning to her favorite example of community banks:

“Because community banks are in the community, and understand the needs and desires of that community as well talent and capacity of community”

Ignoring Kamala Harris's advice and chasing technology-based, identity-specific, or disruption hype cycles might seem appealing in the short term but will cost FSIs dearly in the long run.