Why FSIs Persist with Siloed IT Transformations Despite Predictable Failure

Also in this issue: Four Criteria FSIs Should Use to Prioritize Digital Use Cases for Meaningful Top-Line Growth

Why FSIs Persist with Siloed IT Transformations Despite Predictable Failure

More than two decades after Amazon pioneered most of today’s tech-driven business practices, the majority of FSIs still operate in a traditional, siloed model. They’ve launched digital channels, adopted modern tech and data tools, and partnered with fintechs. Yet, on the dimension that matters most — integrating IT and Data operating models with Business and Operations — they remain fundamentally unchanged.

During a recent leadership call with a mid-sized FSI seeking to transform its operations, I suggested establishing a product team for each core process. The CTO responded, “We already have product teams, Yakov,” and spent five minutes explaining how various IT groups collaborate. When I asked about the COO team’s involvement — since these were their processes we were trying to improve — the reply was, “They’re too busy firefighting to drive this.”

This persistent silo model keeps transformation efforts anchored in a 1990s mindset: “Business should specify what future state they want, and IT will build it.” And in fairness, if revenue-generating units and operations managers aren’t willing to actively lead cross-functional teams daily, IT becomes the only remaining option. The result is predictable — overbuilt, misaligned functionality and bloated projects — but at least it delivers scalable systems if business suddenly takes off.

While readers of this newsletter expect IT-led transformation failures as the norm, some outsiders might find such willful waste hard to believe. When a core modernization project at a Quebec auto insurer doubled its original budget with subpar results, the anti-corruption agency recently launched an investigation. What if that insurer’s C-suite knew how to run transformations and, hopefully, made decisions due to bribes from SAP and IBM?

Big-bang IT modernizations are so pervasive that even leading FSIs like Capital One and Citi sometimes prioritize quantity over quality. Rather than relying on cross-functional teams of skilled employees to gradually transform processes and systems, they choose to move faster by scaling up with external resources. As a result, instead of directly hiring H-1B candidates as employees, they bring in large numbers of long-term contractors through staffing mills that exploit H-1B rules.

A top-down, siloed operating model for transformation is more likely to fail because it doesn’t capture the necessary level of detail for each process and system. When one of the top four US banks recently launched another transformation program, they discovered after planning was complete that their data on the services employees performed was completely inaccurate. Hundreds, if not thousands, of FTEs were assigned to the wrong capabilities to align with internal politics, without ever consulting middle-level executives.

Bain recently quantified how five key decisions can make or break the success of tech modernization in banks. The unfortunate truth is that every C-suite executive in financial services and insurance has intuitively known this for at least a decade. Yet, because incentives remain aligned to maximize program budgets while business and IT continue to be managed in top-down silos, most FSIs knowingly persist in failing. Will you let this continue in your FSI, or do you have the courage to call on Business and Operations leaders to get involved?

Four Criteria FSIs Should Use to Prioritize Digital Use Cases for Meaningful Top-Line Growth

Inspired by Capital One, Oleg Tinkov launched the world’s first digital bank in 2006. Like a traditional bank, it prioritized lending products, targeting the middle-class segment and eventually becoming the country’s second-largest issuer of credit cards. Inspired by Tinkoff Bank’s success, Nubank was launched in 2013 with a no-fee credit card, also targeting the middle-class market. Yet, despite these early wins, most consumer fintechs avoid lending, instead posing as banks while focusing on easier-to-build products, such as payments, savings, and trading.

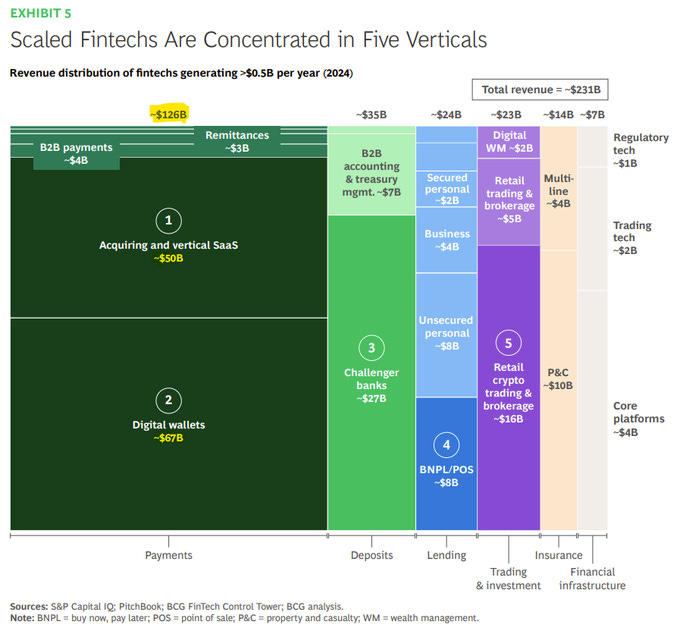

This is a key reason incumbent banks don’t feel threatened by the fintech revolution, because it doesn’t target their core revenue streams. Launching B2B, B2C, C2B, and C2C payments use cases is relatively easy; however, as PayPal found with Venmo, these products often generate little revenue. According to a recent BCG study, after 15 years, all prominent fintechs worldwide, focusing on these four payments markets combined, still generate less than $10 billion in revenue.

Prioritizing use cases around risk-based products with large revenue pools is just the beginning. In some regions, price caps on certain products require approval from executive or legislative bodies, limiting profit potential. Home insurance in the US is one such challenging product, in which the industry as a whole rarely turns a profit. In Q1 alone, State Farm reported an underwriting loss exceeding $5 billion, offsetting it with interest on float and cross-selling life and annuity products.

Once an FSI prioritizes a large revenue market with a significant profit cushion, the next criterion is whether established players lag notably in terms of operating effectiveness and digital capabilities. In other words, “Are they inept enough that, with superior tenacity, we could outcompete them?”

For example, in the US consumer auto insurance market—a large and profitable sector—incumbents like Progressive are powerful in operating model, user experience, and data capabilities. Progressive recently raised prices by 20% without any noticeable impact on customer retention and is poised to become the market leader within a year.

Not surprisingly, the same BCG study of scaled fintechs reveals that worldwide revenue from P&C disruptors across all products and client segments totaled approximately $10 billion. This is approximately half of what Progressive generates in a single quarter alone.

The final criterion, of course, is whether your FSI has the right leader to own that digital use case. Does this person have the passion to dedicate a decade or more of their life to creating a visible impact across the company? Digital growth in financial services and insurance is an exhausting grind—even the best founders eventually want to move on. Today, Jack Dorsey at Block focuses on Bitcoin, while Sebastian Siemiatkowski at Klarna prefers discussing GenAI efficiencies. It’s a pity they both lead fintechs expected to outgrow incumbents.

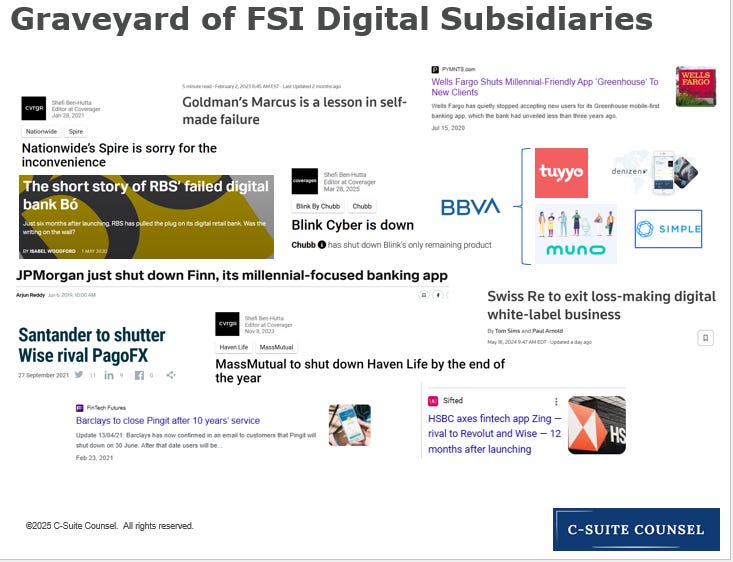

The financial services and insurance industry is littered with failed attempts to launch digital use cases that promised significant impact. Pursuing small revenue pools with razor-thin margins, facing fierce competition, and having traditional executives in charge are key reasons these efforts ended up in the graveyard. If your FSI prioritizes use cases that meet all four criteria, remember this final lesson: never use a different brand name for that endeavor.