Who Is the Dying Breed: Traditional FSIs or Fintechs?

21st-century milestones in the fintech vs. traditional FSIs rivalry, why insurtechs are irrelevant, client segments for FSIs vs. fintechs, why even the best fintechs stop growing but some banks do not

Who Is the Dying Breed: Traditional FSIs or Fintechs?

It's intriguing to liken the financial services and insurance industries to the biological evolution of increasingly fit species, where the progression might be:

Banks -> Fintechs -> Cryptotechs -> Metatechs -> Cleartechs

The argument just a few years ago was that traditional FSIs were a dying breed. 20th-century fintechs like Rocket Mortgage and PayPal proved they could create digital offerings for niche products and specific client segments, which began to dominate banks' offerings. This felt like the beginning of unbundling, slowly dismantling the traditional bank's profits brick by brick. The prevailing wisdom was:

Banks didn't understand technology and were too inert to save themselves.

Banks were not operating like technology companies, whereas fintechs were.

Consumers increasingly sought out excellent digital services.

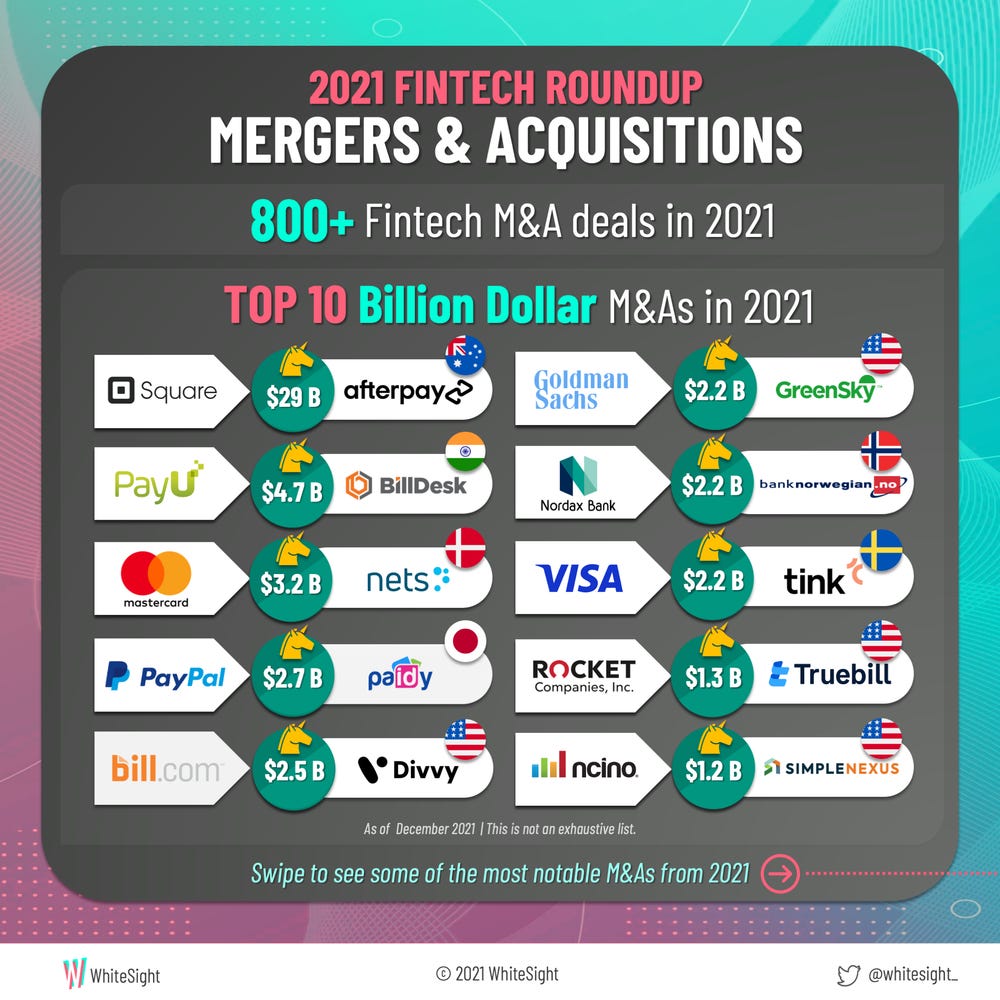

Hence, the common belief implied it was only a matter of time before fintechs would take over. That view was carried further by the skyrocketing fintech valuations and VC funding ('smart money'). Fintechs like Block and Stripe were valued at around $100 billion, and PayPal's valuation exceeded $300 billion, surpassing Bank of America and Mastercard. With over $200 billion in equity funding and M&As in 2021, the fintech sector appeared unstoppable:

Since then, Cash App's non-bitcoin revenue has grown to be among the top 20 consumer divisions of US banks, on par with Fifth Third and Citizens. All top 5 finance app downloads in the US still belong to fintechs, with only a couple of traditional FSIs barely in sight:

But the long-term trend completed a U-turn in the last 3 years, with a fintech sector by far underperforming both the general economy and technology companies:

Surprisingly, some leading fintech experts continue to assert that the unbundling of traditional finance by fintechs is inevitable. They are starting to resemble crypto influencers who confidently claimed in 2014 that crypto would imminently replace Visa and the Federal Reserve while saving the unbanked in Sub-Saharan Africa, and then again in 2018, and in 2023. What are these otherwise knowledgeable people missing, and what can we confidently conclude about the rivalry between traditional FSIs and fintechs?

A Quick Insurtech Detour

The only segment worth discussing regarding the disruption of traditional FSIs is consumer financial services. Business financial services and insurance are less transactional, making revolutionary digital models even less likely to impact them. This is why, even in the small business end of business insurance, there isn't a hint of a contender to the incumbents. For example, Next Insurance, launched in 2015, is still unprofitable, and instead of disrupting the incumbents, it received a strategic investment to stay afloat.

As we discussed in another newsletter, P&C insurtechs for consumers are struggling, partly because they unwisely entered a barely profitable industry with already quite advanced incumbents. However, these firms also made major mistakes. For example, Root Insurance couldn't identify a significant differentiation in its telematics-based auto insurance. It could have remained a minor success through some adjustments. Instead, it decided to align its PR and marketing with the racial upheaval in the US after George Floyd's death. Root spearheaded a campaign highlighting its use of driving data instead of the industry's allegedly discriminatory practice of using a credit score:

Even more damaging to its business performance, Root announced the removal of credit scores from its pricing model. Credit scores are also excellent predictors of the likelihood of filing a claim. Root's stock is now trading 98% lower than at its highs.

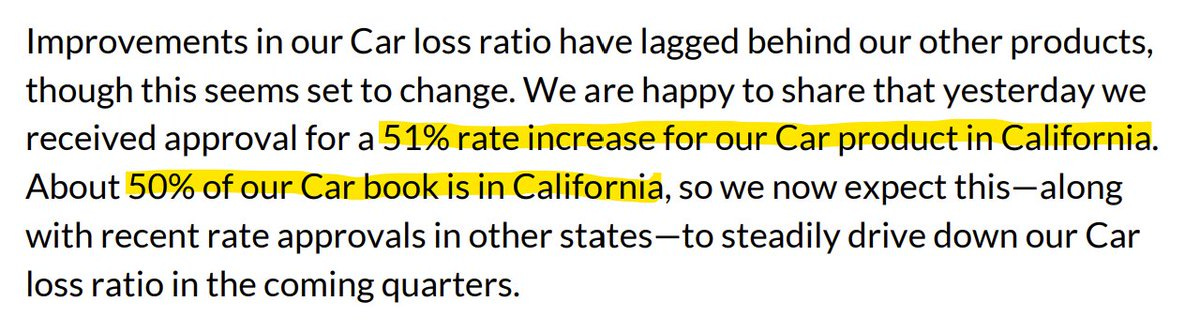

Another consumer P&C insurtech, Lemonade, initially captured a 10% market share of rental insurance in some US states. Its AI-native differentiation seems more like a marketing spin, but it could have remained focused on gradual scaling. Instead, Lemonade began opening offices across Europe and rapidly launching new products. For example, Lemonade rushed to acquire car insurance customers at a low price, with half of the book in California, one of the most expensive states due to car crime and weather elements.

With the stock down 90% from its highs, Lemonade is now attempting to unwind the damage. With growth slowing down, Lemonade grew net premiums only 3% faster in Q3 2023 than Progressive, despite being 130 times smaller and having a higher loss ratio. It doesn't look like its heavily promoted AI-native differentiation has kicked in yet.

Seminal Moment in Retail Banks vs. Consumer Fintechs Rivalry

Let's return to the leading fintechs that had a better chance of making incumbents a dying breed without resorting to bizarre strategies. These startups have been targeting more lucrative niches like profitable lending products, checking accounts with zero interest, or cross-border money transfers charging a substantial markup.

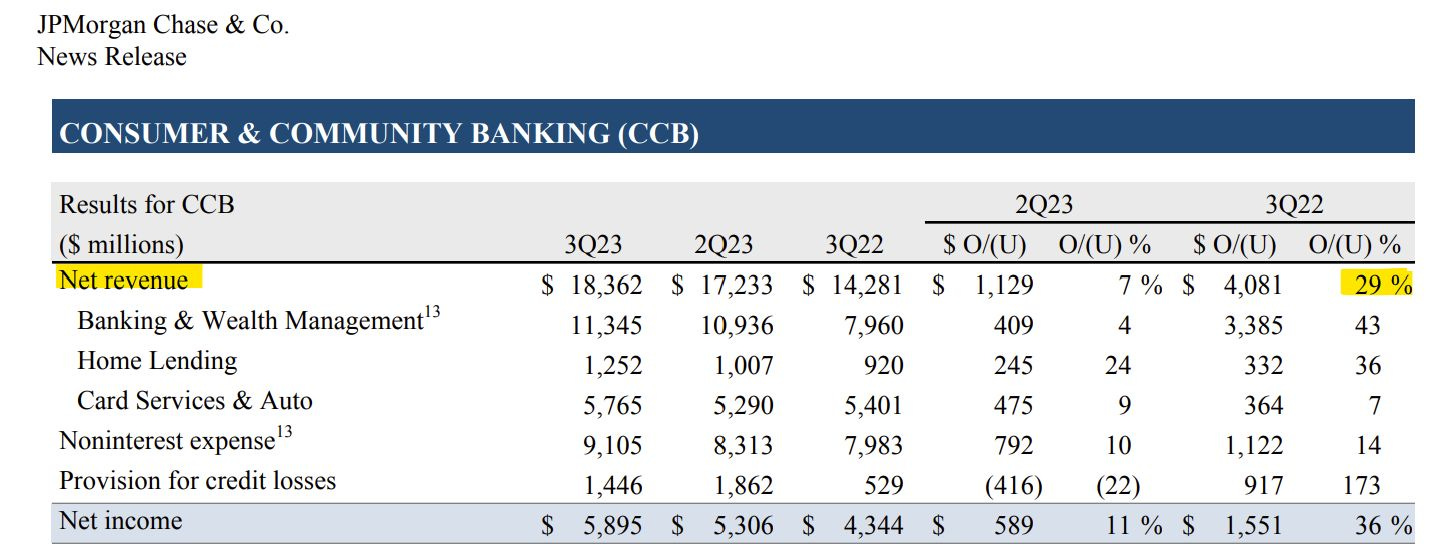

Now is an especially opportune moment to explore whether banks or fintechs will likely become extinct. In a seminal milestone, in Q3 2023, Chase grew its consumer banking revenues by 29%, which was higher than its fintech contenders like Cash App or SoFi (26% and 27%). Crucially, Chase accomplished this while being massively larger. For comparison, Chase's quarterly revenue has grown since 2022 by a similar amount as the total quarterly revenue of Cash App plus SoFi.

Just a year earlier, Cash App was growing 4 times faster than Chase (60% vs. 15%) and at least had a hypothetical chance to catch up one day, rather than remaining 15+ times smaller. Another high-flying fintech, SoFi, is 30+ times smaller than Chase, and more crucially, it is also rapidly decelerating, much like Cash App:

What drove such a surprising turn of events since the euphoria of 2021? In short, consumer fintechs failed to offer significant differentiation compared to banks to profitably poach a large share of their customers. Most of the so-called differences in fintechs just ended up being fewer channels, without branches or direct mail. The fallacy in viewing this as a win is due to thinking of those channels as wasteful legacies that banks are too bureaucratic to shut down. In reality, banks maintain them because they are profitable, as we discussed in a recent newsletter.

As long as traditional FSIs learn how to digitize their channels and quickly replicate the product features of leading fintechs, pushing them out of business evidently becomes impossible. At least, we don't know of any fintech capable of achieving such a feat yet. For example, Remitly is the world's largest remittance fintech by revenue and the second-largest after Wise by money transfer volume. After 12 years, its revenue is still growing by 40%, and it's worth over $3 billion. Sounds promising, right? Remitly appears to be a disruptor ready to take on incumbents like Western Union and Moneygram.

However, that seems unlikely as Remilty is sustaining its growth by spending 25% of its revenue on marketing, while its technology spending has become less scalable in the recent quarter, also reaching 25% of the revenue:

Disrupting incumbents profitably seems impossible, and doing it unprofitably is unsustainable. But why are consumers not naturally gravitating toward these leading fintechs on their own?

Are There Consumer Segments Dominated by Fintechs vs. Banks?

For almost a decade, consumers have increasingly prioritized the quality of a mobile app over the proximity of branches. That should have boded well for fintechs, which are universally exalted for their customer-centric approach and much faster refinement of digital UX.

That might have been the case a decade ago, but today, leading FSIs are generally receiving high marks from their customers for their mobile apps. Sometimes, these ratings are even higher than what leading fintechs receive from their customers, albeit possibly due to lower customer expectations.

It's also important to consider how younger consumers become bank customers in the first place. They are unlikely to have a strong brand opinion on Chase vs. Cash App or SoFi. Quite often, especially in well-off families, the first bank account is opened for a teenager or college student by their parents or grandparents as a gift. Once they finish college and start earning a living, why bother with opening another account if it already works okay?

Incentives obviously work; for some young professionals, it could take $500 to switch an account to another bank, and for others, $1,000. Traditional FSIs are aware of this and have been offering such incentives themselves through direct mail or in-app promotions if a consumer already has a credit card product with that bank.

Those incentives add up. Chase gained 1.6 million net checking accounts in 2022. To acquire a similar volume of customers, a fintech would have to spend $0.5-1 billion annually on incentives alone, while many of them are still unprofitable. And that doesn't even guarantee that those same customers won't jump on an incentive from another provider afterward.

The big hope for fintechs a decade ago was a much cheaper acquisition channel of referrals, akin to Uber. The thinking was that the younger generation is more skeptical and would prefer to rely on recommendations from their peers rather than traditional advertising. However, Uber was offering an entirely new experience compared to taxis. Today's banking is fundamentally different - consumers would be hard-pressed to identify differences in digital features between a leading traditional bank and a fintech. Hence, it is hard for a person to recommend some exceptional feature specifically to sway a friend into switching from a traditional bank to a fintech.

To be clear, it’s not that referrals are not working. But they are not cheap and are offered by traditional players even more than by fintechs.

So, fintechs are going after similar customers with a similar business model, and their technology capabilities are no longer much better than traditional FSIs. Why wouldn't they focus on so-called underserved client groups instead of trying to poach the most popular banking customers?

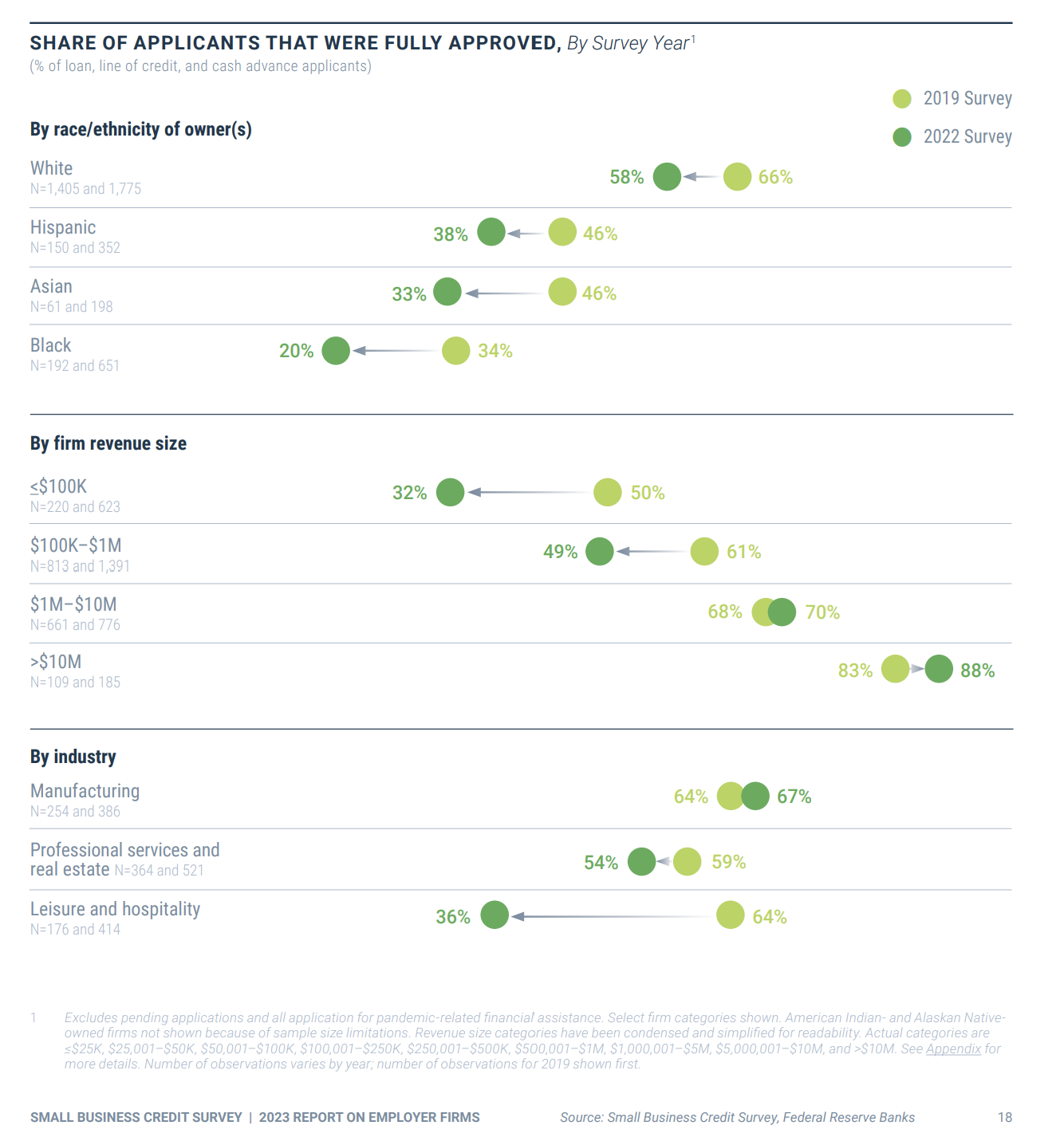

That is not easier since there is a risk-related reason why those clients, like black small business owners, are underserved. Notice how fintech and FSI executives loudly complain about 'white-male-dominated' banks that refuse credit to a lucrative underserved segment yet never jump on that opportunity themselves.

Pandering to social causes aside, fintechs are constrained by a digital mindset, while many of the underserved segments require and prefer a more hands-on engagement. For example, for a lending product, an ideal interaction would be in a local office so a struggling client could more effectively learn in person. Moreover, this allows a lending advisor to more effectively manage such a risky segment based on unique insights from the local clientele and the town's macro environment.

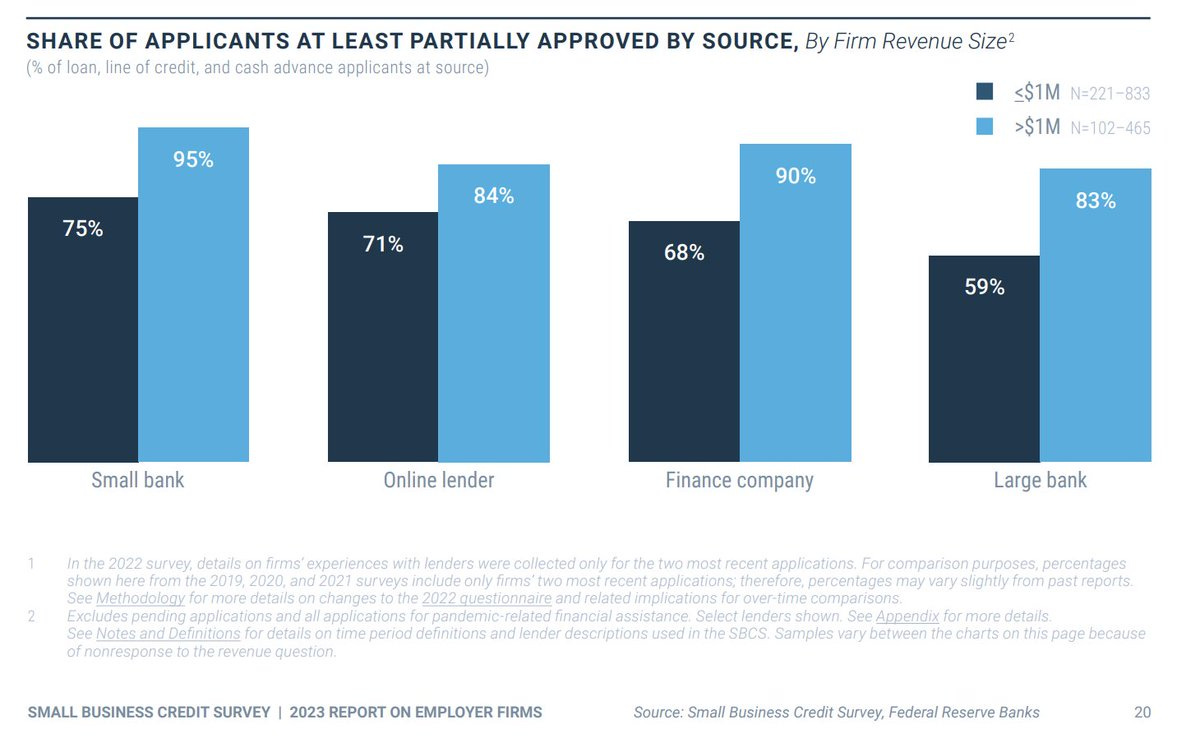

Say what? A human-based engagement model with branches - that is so uncool. Instead, fintechs will keep trying to poach client segments where the approval rate is already 80-95%, like larger small businesses:

To be fair to fintechs, they did address some needs in the underserved client segment. With the government expanding APR caps to 36% and loud media exposés when banks try to collect from delinquent lower-income customers, traditional FSIs got wiser and started avoiding those segments. There is an inside fintech joke that their biggest innovation was to lend to customers that banks avoid due to regulators and media scrutiny.

Hopefully, fintechs can serve those clients profitably, and it will add to their overall growth. Will it help with disrupting incumbents? Nope.

Are Fintechs Better with Risky or Costly Initiatives?

A similarly risky proposition that traditional FSIs are staying away from is crypto. Cash App is generating almost 70% of its revenues from Bitcoin. A large portion of those customers have no business putting money into such an extraordinarily speculative instrument that charges a high margin. Ironically, Coinbase is promoting exactly that dissonance while charging 1-4% in fees.

That is a consistent challenge with fintechs - outside of small arbitrage or dangerous speculations, there is usually no sustainable differentiation. Relying on a Facebook feed or a driving record instead of a credit score sounds innovative, but it has little or even a negative impact on a business model. Once investors realized the lack of a 'secret sauce' against traditional FSIs, unicorns began losing their appeal in 2022.

On a more tactical level, one difference in fintech business models is charging for subscription access explicitly. For Cash App, a recurring portion represents 90% of its non-Bitcoin revenue. Some of the lower-income segments find it more welcoming compared to a traditional bank that usually advertises no fees above certain balances.

Finally, many of the leading fintechs have engaged in acquisitions to fuel their growth. Similarly to traditional companies, most of these acquisitions fail because they are never properly integrated and are conducted at excessively high prices. Consider all the acquisitions that transpired around 2021 before a subsequent 50+% drop in valuations:

PayPal is the best illustration of the failure of such a strategy. Instead of learning how to grow organically, the fintech has relied on dozens of acquisitions for growth. The odd hope was that maintaining silos and separate brands would create some internal synergies. Instead, it obviously led to rapidly declining growth and a change in the CEO and others in the C-Suite to more corporate types, with no expectation that growth would ever come back to at least above 10%.

The Unbearable Tediousness of Being a Perfect Fintech

But there are rare exceptions - a leading fintech that is not wasting time on shiny initiatives like crypto, pandering to the mystical unbanked, or indulging in the glamour of deal-making. Instead, it keeps its head down, focusing on execution. Such a more fascinating, a-la Amazon business model differentiation example is Wise (formerly TransferWise).

Almost a decade ago, I founded SaveOnSend as a fintech in cross-border money transfers for consumers. My thesis was wrong, but I have been fascinated by this poorly understood sector ever since. Following Wise all these years, one of the top 10 most effective fintechs globally, at least until recently, has been a fun and insightful endeavor. Wise's business model innovation was like Amazon in e-commerce, creating a flywheel centered on expanding customer engagement quality at increasingly lower prices.

Indeed, Wise was charging about 5 times less than its main competitors among banks and lower than money transfer specialists like Western Union and MoneyGram. Its digital UX and human customer service were superb, and it built an industry-leading playbook for refining its business, operating, and technology models. Similarly to what happens even with the most successful disruptors, it took Wise a few years to find its message, but then it took off, catching up in consumer transfer volume to the industry's “800-pound gorilla”, Western Union, within a decade.

Wise also avoided the major mistakes of prematurely launching unrelated products and opening new regions before reaching scale in its core business. However, while the combination of a business model differentiation and superb execution resulted in remarkable success, Wise's growth has been declining, falling below 10% by mid-2023:

In other words, a unique fintech, a true unicorn, finally reached a scale to cause disruption to banking and specialist competition if it could only maintain a growth velocity, but it can't. Why not?

In short, the competitors got much better at closing price and service gaps where it mattered, and after a decade of brutal scaling, Wise's original leadership team ran out of steam to keep inventing new tricks. One of the co-founders left, another finally wanted to balance more time on raising children, while some others departed. The new additions were mostly from the corporate world. They were all strong professionals but had never personally experienced the years of pain of breaking through the steel walls protecting the clientele of FSI incumbents.

Traditional FSIs: Size Matters, But Not Only

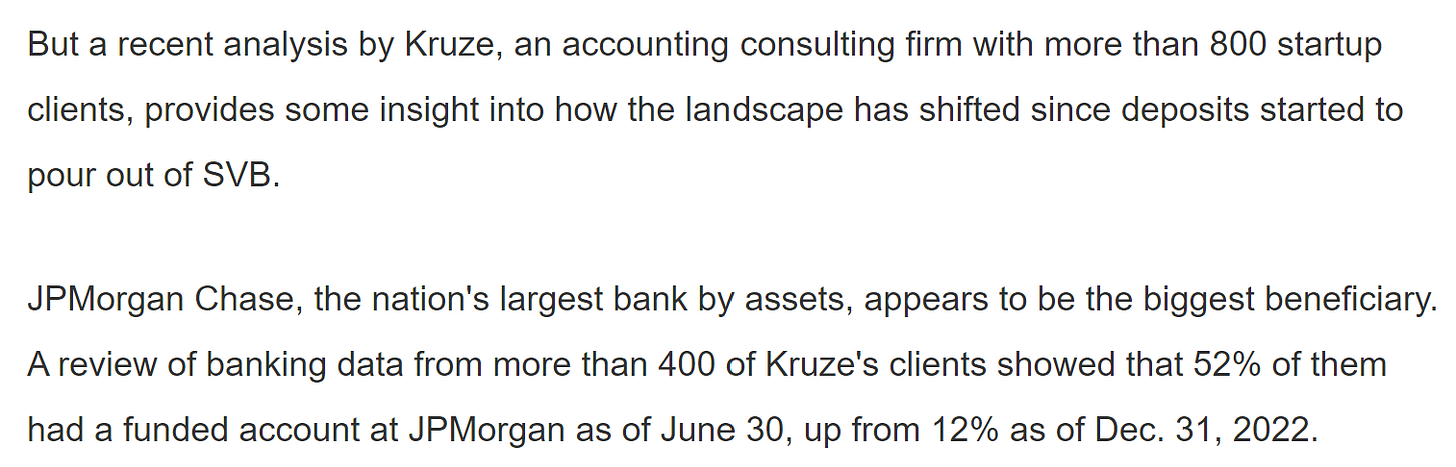

Another nail in the fintechs' disruption of banks' coffin was hammered in March 2023 when many consumers and businesses got scared by the defaulting of Silicon Valley, First Republic, and Signature banks. As a result, they removed deposits from other mid-size banks, leading to a 25% drop in their valuation, which hasn't since recovered. Digital maturity didn't matter for the defaulting banks and didn't matter to the banks losing deposits, albeit, it might have made it easier to move money out.

For our discussion, a more interesting question is where those deposits went: to innovative fintechs or traditional large banks? The largest banks gained more than 50% of the panic-driven outflows, with the rest going to asset managers like Charles Schwab. No fintech reported a billion+ deposit inflow in that period. Even startups moved their accounts to Chase rather than to some neobank:

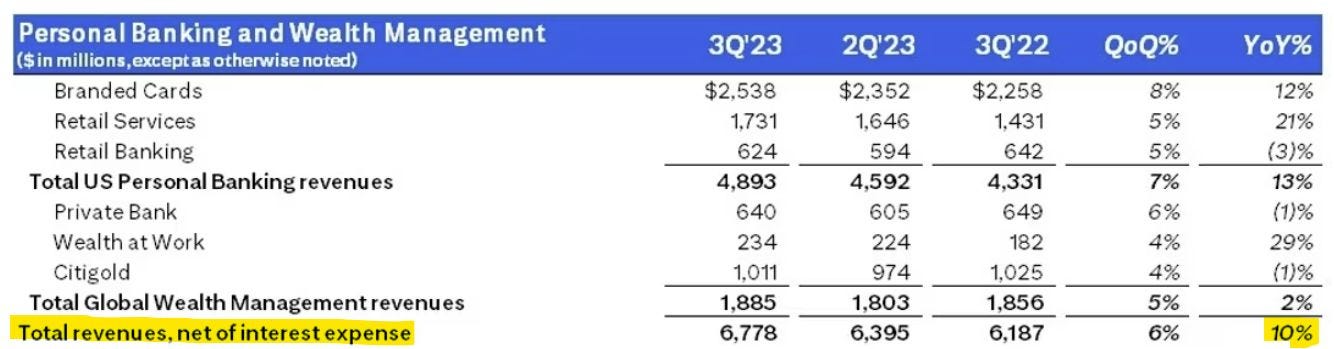

Not only do consumers prefer large banks in times of crisis, they don't view all banks similarly. Compared to other retail divisions of top US banks, Chase is in a league of its own. For example, Citi is growing three times slower while being three times smaller:

Even against Capital One, Chase has a much higher growth trajectory and a higher valuation multiple of revenue. How is this possible since almost every expert views Capital One as a huge success in digital transformation?

Those experts are incorrectly assuming that digital capabilities have some magical power to attract all consumers when it really matters only to some. More importantly, Chase happens to be a premium brand, while Capital One is a mass brand. So, since their digital capabilities are similar, a large portion of well-off consumers with a lot of money would not consider banking with Capital One instead of Chase unless they are poached with a prohibitively high incentive.

As a result, Capital One is stuck with a mass segment that is more susceptible to changes in the economy, and hence its total revenue has been fluctuating around the same numbers:

JPMC is not even the largest technology spender among leading FSIs relative to its revenue, and its CEO and CFO recently grappled with explaining this spending purpose. However, the combination of Chase's business, operating, and technology models is superior to other banks, so Chase is winning among its peers while leaving consumer fintechs farther behind.

In Conclusion: The Devolution and Impact of Leading Fintechs

Paraphrasing Tolstoy, all successful growing fintechs look the same, but once they start slowing down, they have their differences. Whether it is due to boredom, lethargy, or vanity, the formerly best-in-class fintechs are becoming less effective.

They start hiring more corporate types who don't have the veracity to muscle out the competition but are familiar with rationalization activities: shared services, simplification, M&A deals, etc. - all are distractions from finding a leverage spot to break through to someone else's customers. That is why, even the best fintechs are not a threat to incumbents.

While leading fintechs are being pointed in the suboptimal direction, they are, in effect, starting to devolve on the operating maturity curve. At the same time, FSI incumbents keep slowly getting more effective:

In conclusion, FSI incumbents are definitely not going to die, and the best fintech companies will also continue to thrive. Since they don't possess enough determination to see incumbents going out of business, these fintechs will keep pursuing increasingly obscure markets. For example, Revolut recently announced a new initiative for the 1% of Americans who are in the country temporarily and don't have much money:

What is becoming increasingly clear is the barbell trend that I first saw in Ron Shevlin's post in 2020. Leading fintechs are superb at getting a large share of young first-time customers while poaching existing customers from small and regional banks. The top banks, especially as good as Chase, will continue to dominate well-off customers.

Moreover, fintechs have been a great impetus for change in traditional FSIs. Xoom woke up Western Union to take digital channels seriously, Ripple scared SWIFT into building GPI and GO products, Venmo pushed the US banks into implementing their P2P solution, Zelle, and many other cases.

There is not much more revolutionary beyond that. Rooting for the underdog is fine, but remember the main lesson from Michael Lewis's Moneyball - all the innovations made the Oakland Athletics much better to start winning numerous games in a row. Unfortunately, to win over incumbents on a national stage is so much harder - the baseball team hasn't accomplished that in more than three decades and has no chance in the foreseeable future.