Scaling Dilemma in the Digital Transformation of FSIs

Also in this issue: Why FSI CEOs Struggle to Justify Their Extensive Technology Expenditure

Scaling Dilemma in the Digital Transformation of FSIs

The objective of digital transformation is to significantly accelerate business value creation. Effective FSIs achieve this in two ways: by establishing unique digital sources of revenue and by implementing scalable shared services. The former is extremely challenging due to the need for a high level of digital maturity, leading to many unsuccessful attempts by FSIs. However, the scalability aspect is more attainable.

Listening to FSI executives and third-party experts, scalability appears to be a no-brainer. Automating technology processes to support limitless business growth with minimal additional cost - what are the drawbacks?

Can Customer Support Scale?

Certainly! In the realm of customer support, digital transformation use cases have been effectively implemented over the last decade, with growing success driven by advancements in machine learning. In a recent interview Jim Fowler, a Chief Technology Officer of Nationwide Insurance, provided an example of this transformation in the handling of auto insurance claims:

According to Fowler, 50% of all auto insurance cases are now handled by intelligent bots, which are used to make repair cost estimates, determine payouts, and route rental cars to a customer. This means associates “aren’t doing the clerical side of the job…”

These use cases offer a trifecta of scalability benefits: reduced transaction costs, savings from mitigating customer fraudulent behavior, and an increase in value-added employees.

But even customer support is not uniformly scalable, with branches serving as the most vivid example. As we discussed in another newsletter, branches continue to provide significant value for financial services and insurance companies. Yet, over the last three decades, the media has consistently highlighted the impending demise of these physical locations. Since many experts and journalists seldom visit these branches, they have been perplexed by their continued existence and actively seek out any signs to support their biases:

In reality, the number of branches per capita has been declining by less than 1%. A significant portion of this decline is attributed to the acquisition of banks with overlapping geographical footprints or the disappearance of smaller players. Large institutions continue to open and close dozens of branches annually, resulting in only a slight negative change in the net outcome. For JPMorgan Chase, the net decline in 2022 was 11 branches, which represents less than 0.3% of their total network.

As customers perceive in-person customer support as a key differentiator, investing in scaling the in-branch experience could be counterproductive. While it might seem simple to lower the cost per interaction, it could result in substantial customer attrition.

Can Sales Channels Scale?

A nuanced approach is also needed for customer acquisition. It's evident that efficient digital channels have been a cornerstone of traditional FSIs for over two decades, beginning with credit cards and auto insurance. However, 20th-century channels are still effective, and replacing them with more scalable digital channels would be counterproductive.

For example, direct mail remains a substantial sales generator for financial services and insurance companies, involving billions of pieces in the US. Out of the top 5 products marketed through direct mail, FSIs hold the #1, #3, and #4 positions:

Branches continue to be a significant sales driver for more complex FSI products. Much like buying a car or a home, the majority of consumers still require the comfort of interacting with a sales representative in person before committing to a substantial loan or life insurance investment. In fact, part of the value proposition for these products lies in the in-person advice and follow-up.

Naturally, Wells Fargo attempted to scale sales in branches by adding phantom accounts to customers more than a decade ago, but such a practice has since been frowned upon. As a result, branches have primarily focused on marginal digitization rather than full digital transformation.

Which Function is the Least Scalable?

Frequently, FSIs mistakenly allocate their top digital transformation resources to enhancing secondary services that won't fundamentally improve business outcomes. This is often done because these systems might be easier to automate or because certain executives hold more political influence. However, there is one function in FSIs where there is significant external, rather than internal, pressure to essentially waste funds.

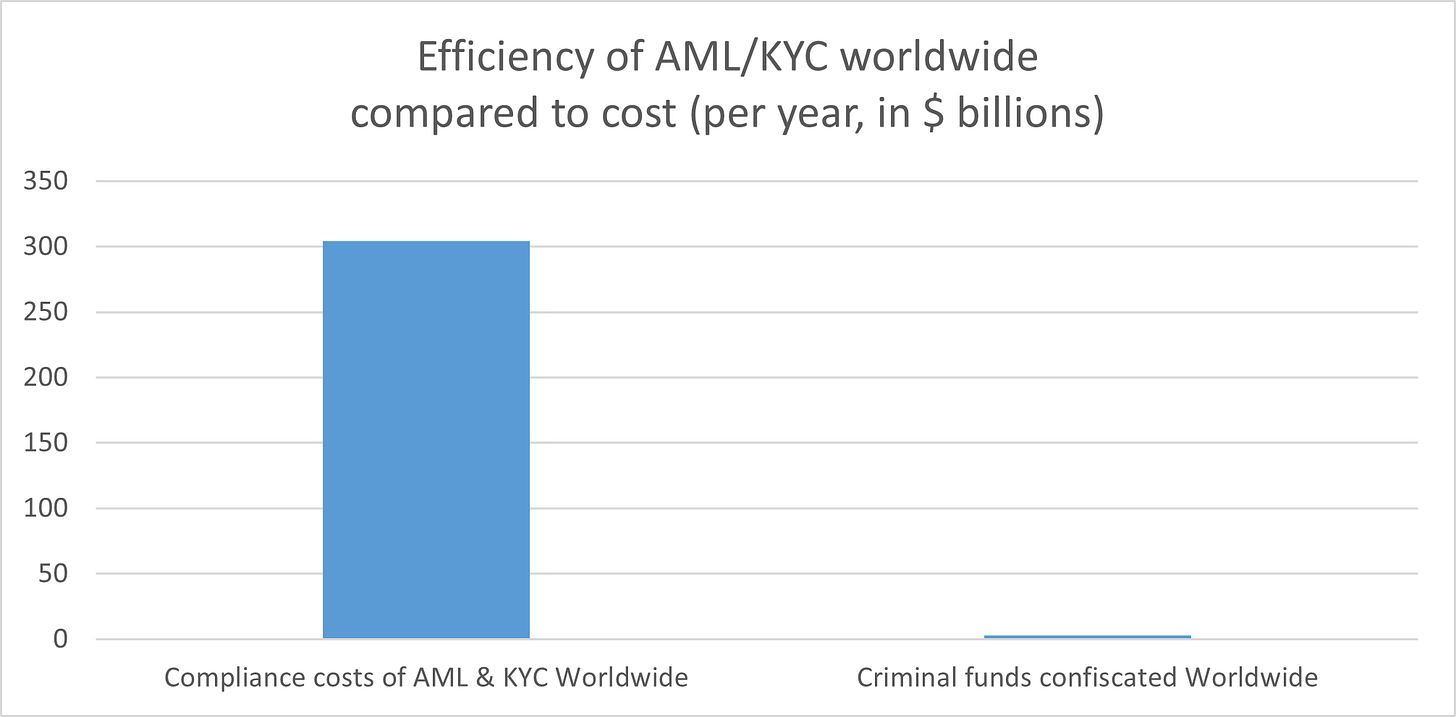

Rather than enabling financial services and insurance firms to transform this area and allocate resources to value-added services, a regulatory black hole is absorbing an increasingly higher proportion of the overall expenditure without significant impact on the end results. Welcome to the Compliance dystopia for AML (Anti-Money Laundering) and KYC (Know Your Customer) capabilities, sometimes grouped under the Financial Crimes umbrella.

For example, in the Payments industry, risk and compliance management accounted for 36% of the total costs, making it the largest spending category:

After three decades of implementing AML and KYC capabilities in financial services and insurance companies, these efforts are primarily driven by the need to avoid regulatory fines rather than the actual eradication of the problem. The main reason for this is the misaligned incentives. Terrorists, despots, corrupt politicians and tax evaders, and children and drug traffickers are detrimental to their foreign countries but beneficial to the countries and businesses used for transferring, moving, and parking their assets.

Therefore, there is still a lack of understanding regarding whether these substantial expenditures are effectively reducing instances of financial crime. Wait, there is an understanding. That answer is 'no.' For every $100 spent on AML/KYC capabilities, only $1 is collected in criminal funds, and there is no evidence that the underlying crimes have been decreasing worldwide.

Instead, FSIs are optimizing for opaque government oversight because the government is not incentivized to reduce financial crimes, as those funds could potentially enrich other developed countries. FSIs check the necessary boxes to avoid fines, and in many cases, real investigations only occur when requested by law enforcement agencies.

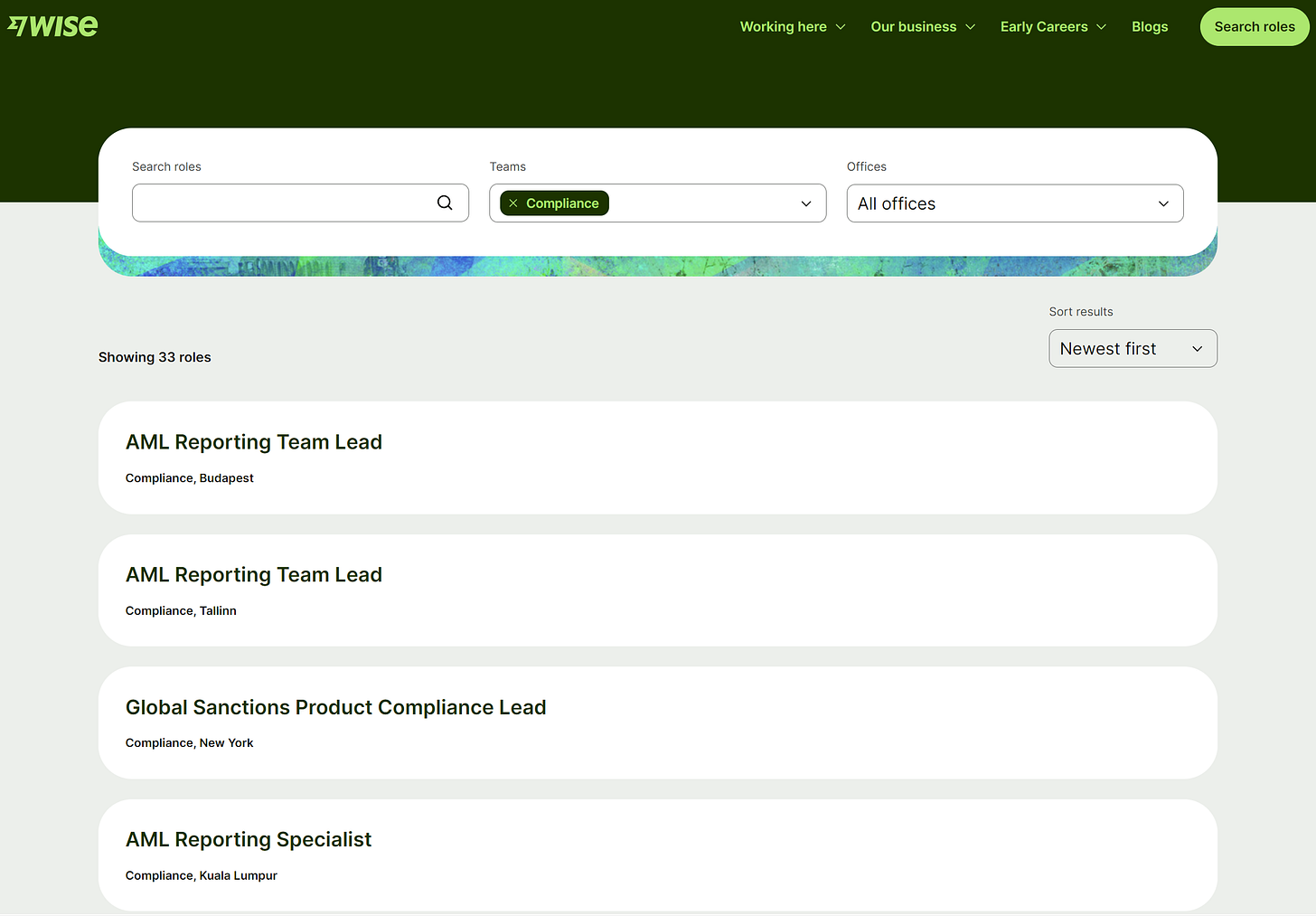

Even the best fintechs seem to have given up on further scaling this function through digital transformation. Out of the currently available roles at Wise, 24% are in Compliance:

That is bad enough, considering there's no significant impact on seized criminal funds or some other business outcome. But can you imagine a leading fintech boasting about being unscalable? Even more so, bragging about doubling an already massive headcount in an area that not only has no business impact but is designed to frustrate numerous law-abiding customers? Behold: the Financial Crime Spectacle by Revolut!

Why would Revolut, known for its tough-love-get-things-done-growth-focused culture, engage in such wasteful practices? Revolut, in its pursuit of obtaining a banking license and addressing government concerns about its AML/KYC practices being too lax, felt the need to demonstrate its commitment to the UK government and other relevant parties, taking their perception seriously.

Digitally transforming Compliance would be counterproductive to the ultimate goal of making government bureaucrats believe that the company is allocating sufficient resources to the problem. Imagine suggesting to a government executive that digital transformation could reduce his staff by half – that might result in your last meeting with them. They typically equate effort with the outcome while measuring said effort based on the headcount involved.

To be fair to government employees, there is one area where their quality is top-notch: tax collection. Since domestic tax evasion, as opposed to foreign-born financial crimes, has a negative impact on the country's finances, the IRS has superb effectiveness, returning $12 for every $1 spent on auditing high-end consumers. Of course, politicians are incentivized to make tax laws as opaque as possible to maximize donations from wealthy donors, but that's a different story.

A deep-thinking FSI executive appreciates this trap of uniform scalability. Digital transformation is very risky and expensive, and it is constrained by relatively few employees who know how to carry it out. Prioritizing the functions where digital scalability creates a trifecta of benefits while leaving other areas for gradual improvement is the difference between transformation success and failure.

Why FSI CEOs Struggle to Justify Their Extensive Technology Expenditure

It is obvious why digital vendors and consultants have consistently advocated for end-to-end digital transformation, including the complete replacement of legacy systems. Maximizing FSI spending is directly linked to their revenues, which, in turn, are directly tied to stable employment and bonuses. However, the recent trend of FSI executives boasting about their massive technology spending is a counterintuitive phenomenon.

Wouldn't wasteful spending shrink an FSI's profits, which is directly linked to an executive’s job security and bonuses? This is definitely not the case for IT executives, as in the 20th century, most of them are still not measured based on the P&L impact. Simultaneously, maximizing budgets adds to their political weight and allows them to implement cool technologies. However, the individuals who have been bragging the most about it lately have not been IT executives but CEOs and CFOs, which seems puzzling.

One explanation is the short-sightedness of the unsophisticated sell-side research analysts. For a while, around 2021-2022, they simplistically equated spending on technology by traditional FSIs with higher multiples for fintechs. When the leading fintechs were valued at 10-30X of revenue, FSIs that spent more on technology may have deserved 5X by proxy. Being more like fintechs and, thus, deserving fintechs' valuation was one of the major drivers of the arms race in technology spending (see this newsletter).

But with fitnechs severely underperforming broader indexes more recently, even the most pattern-following analysts realized that technology spending doesn't necessarily translate into P&L impact.

Moreover, the recent 180-degree turn by Truist, pressured by analysts, from a technology spending bonanza to cost-cutting, should have been a warning to other FSIs to start preparing for a pivot. But the bigger the ship, the longer it takes to turn. With the recent quarterly earnings of the US's largest banks, the disconnect was on display when research analysts asked the presenting C-Suite why they kept spending billions on technology.

JPMorgan and Bank of America Missed The Pivot

Mike Mayo, Wells Fargo Securities analyst, posed a timely question to JP Morgan's leadership: "Does it really help to be the biggest tech spender in the banking industry?" The first surprising response came from the CFO, Jeremy Barnum:

“I just think like it's sort of mandatory, right? I mean, we're big and very technology-centric business, and the world is competitive. And everything is changing. Younger generations have different expectations, and we have to be nimble, and we have to be on our front foot. And otherwise, we risk getting severely disrupted.”

A CFO who views ongoing technology spending as obligatory due to the desires of younger generations or potential disruptions is not just repeating a decade-old cliche but also undermines their primary role, which is to provide checks against such esoteric statements when they come from their business counterparts. When JPMorgan became my client two decades ago, wasteful technology spending was already the norm, but I couldn't have imagined, as a consultant, that its CFO would be so casual about it.

At a minimum, JPMorgan's CFO could have responded that while the bank is indeed the largest technology spender among FSIs, relative to revenue, the amount is actually on the low end. However, as Jeff Bezos explained, focusing on competitors can create negative energy for a leading company, so perhaps the CFO didn't want to fall into that emotional trap.

JPMorgan CEO, Jamie Dimon, likely places even less importance on benchmarking technology spending, but his response was more specific, albeit even more surprising. He first named competitors among fintechs:

“Just the competition, we look at it is it's Wells. It was coming back, which I'm happy for you guys. It's obviously, Marcus, it's Apple. It's Chime, it's Dave. It's -- a lot of people coming up with these businesses in different ways. Some have been quite successful. It's Stripe in payments. And so we want to be very good and very competitive.”

Wells Fargo has been plagued by scandals and has the same stock price as a decade ago. Marcus was a complete failure and is no longer in business. Dave experienced an existential drop in valuation and has minuscule revenue compared to Chase.

Apple, Chime, and Stripe are more accurate competitors, so, fine, Jamie's overall list of fintechs is from 2021. But, more importantly, to the analyst's question, how JPMorgan's billions of technology spending are helping against those competitors? No idea - instead, Jamie offered these additional technology spending categories:

“Some of that tech spending… is cybersecurity, data center resiliency, regulatory requirements, and things like that, which we simply are going to do and be very, very good at to protect the company.”

Protecting the company against criminals and regulators is undoubtedly important, but how the billions of technology spending is enhancing those efforts on top of the existing capabilities remains a question.

Regarding Bank of America, another newsletter explained why its CEO calling the bank a "technology company" doesn't accurately reflect the reality of its business and operating models. The recent analyst call provided simpler evidence.

The same analyst asked a similar question: “You've invested for over a decade in your data and tech stack and digital engagement… Why do you think that you have an advantage versus, say, smaller banks, fintechs, or big tech?”

The Bank of America CEO, Brian Moynihan, responded by highlighting three areas:

Savings from chatbots reduce customer support expenses;

A 10-15% reduction in app development costs per effort; and

Owning thousands of AI/ML patents.

The first two areas are potentially more advantageous than the ones in the response from JPMorgan's CEO, but could the business benefit be significant enough to justify billions in technology spending? As we often discuss, chatbots could be a major source of customer complaints in the realm of digital innovation as they often fail to address more complex questions.

Furthermore, notice the most frequent ways clients utilize Bank of America's chatbot, named Erica. Most of these uses neither save a significant amount of time for customer support staff nor generate substantial additional revenue for the bank.

Reductions in application development costs are similarly questionable. For an FSI like BofA, mostly in the IT Product phase of digital transformation, cheaper application development to produce more software could be risky. Without a Business owner driving those efforts, what are the chances that cheaper and faster-written code will generate a significant business impact?

Why Can't Top FSIs Offer Insightful Responses?

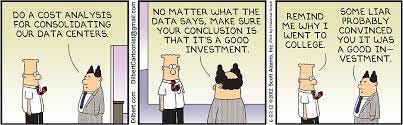

How is it possible that the CEOs and CFOs of the world's top 10 largest banks don't have a thoughtful response to such a timely question? It's not that they were caught by surprise; it's that they don't know the answer.

The primary reason for substantial technology spending on digital transformation always comes down to accelerating P&L impact. P&L impact is significant on its own, but increasing it at a faster rate is what drives the FSI's valuation multiple. Otherwise, an FSI could be spending billions on technology or be one of the most innovative regional banks, and yet five years later, have a lower valuation.

In an ideal scenario, a C-level executive in a leading FSI should clarify how technology spending is generating significant additional profit. However, thus far, the strategic efforts of traditional FSIs have often failed to create significant value justifying massive expenditures.

Think back to our Blackrock Aladdin interview, and consider how many success factors had to align for it to work - the most ironic being that Aladdin's success was accidental. Yes, it is now a success story with over $1 billion in revenues, growing at 20%, but it didn't become commercial until another money management firm asked to use it.

Even developing Aladdin code for internal use was accidental rather than a deliberate strategy. In the first couple of years, when it was known as Blackstone Financial Management, the company hired a software development leader, Gary Maier, who happened to be a brilliant developer. When he initially proposed creating code that could scale across various asset classes, a Blackrock co-founder rejected his idea.

Luckily for Blackrock, Gary had the vision and persistence to move forward and create Aladdin under the radar as a skunkworks project. Since the early '90s, massive spending on compliance and other intermediaries between IT and Business would make such under-the-radar effort unlikely to get to production.

Even that would be just the start. Aladdin's other secret weapon was superb marketing. Some of the senior business executives personally got involved to create a significant buzz around this innovative platform, despite its at times mixed functional performance.

If proactive digital transformation frequently fails, and impactful efforts often occur by accident, an FSI CEO who can articulate the business value of significant technology spending is unsurprisingly extremely rare.

What Should FSI CEOs Do in the Future?

Large FSIs are too complex for a CEO to comprehend the details and be personally involved in driving specific digital transformation initiatives. However, instead of making uniform pronouncements or enforcing top-down strategies, they should delegate accountability to front-line executives (Tribes in Agile terminology) and trust and enable their success.

This is what makes JPMorgan more digitally mature than Bank of America or Citi - looking past superficial pronouncements, Jamie Dimon has recruited stronger front-line executives and provided them with more autonomy. Consequently, its Consumer Banking business is not only 2.5 times larger than other large banks like Citi, but it is also growing almost 3 times faster (in Q3 2023: $18B at 29% growth vs. $7B at 10%).

With front-line empowerment firmly established, before future analysts' calls, FSI CEOs should inquire with those executives about how they are benefiting from massive technology spending. Hopefully, they are closely connected to their technology teams and personally prioritize their impact and capacity. Otherwise, all analysts will eventually realize that those extra billions of technology spending weren't a good investment.

Other Insightful Reads

Allstate’s cloud-first approach to digital transformation pays off