PayPal's Failure to Shock Highlights the Difficulty of True Innovation

Also in this issue: The Persistent Myth of the Digital Revolution Despite Mounting Evidence

PayPal's Failure to Shock Highlights the Difficulty of True Innovation

A newly appointed CEO might naturally feel pressure to make some groundbreaking announcements in their first few months on the job. On January 17th, in his inaugural interview, PayPal’s new CEO made an extraordinary promise to "shock the world," highlighting three longstanding issues predating his tenure:

Lack of strategic focus

Lack of customer innovation

Too many acquisitions

This is consistent with our October profile of PayPal, describing its failure to integrate 26 companies that it acquired for $15 billion over the years. Such a lack of focus was exacerbated by mediocre spending on technology without a data and platform monetization strategy.

The easy solution for PayPal would be to announce a divestiture of previous acquisitions like Xoom and the shutdown of marginal initiatives like its stablecoin. The customer innovation part is much harder because it would require PayPal to launch a product feature that is much more impressive compared to its high-caliber peers like Square and Stripe.

A week after the interview, PayPal unveiled six “new” innovations that were meant to revolutionize global commerce:

Maybe two decades ago, these features would indeed have been revolutionary; a decade ago, they might have been considered innovative, but these days, they are marginal improvements expected from any FSI. For example, Grant Karsas, VP of Digital Experience at Travis Credit Union, recently described such improvements in an interview with The Financial Brand:

“… we recently examined our digital account opening process. By analyzing each step, we identified one friction point causing a 10% drop-off. Resolving this through an improved user experience will exponentially impact member acquisition.”

To innovate successfully, PayPal needs first to identify where it has a significant data or platform differentiation against its peers and then monetize those advantages. Instead, the company is focusing on cutting checkout time, which is helpful but not likely to significantly disrupt its competitors' businesses. Hence, PayPal's stock dropped 4% on the day of the announcement.

PayPal’s conundrum is common for many large FSIs - they launch too many easy initiatives, including partnerships and acquisitions, rather than taking the much harder approach of winning market share with internally developed differentiation. We already discussed in the recent deep-dive on FSI’s R&D and Lab groups how the abundance of technology funding has created perverse incentives for large players like Capital One and Fidelity. They pilot numerous features rather than creating a significant revenue impact, resulting in amusing juxtapositions, such as during a recent analyst call with Capital One CEO Richard Fairbank:

Leading with technology, digital capabilities, or an innovative process can only be celebrated when it generates significant revenue to justify the risk, not when the revenue declines by 7% - then it looks more like a waste. The recent interview with U.S. Bank’s chief innovation officer, Don Relyea, and his team, further illustrates this issue:

He and his team not only seek to spot new tools and techniques to improve bank processes, but products that could represent new financing opportunities for U.S. Bank. Case in point: Genesis Systems’ WaterCube. “It’s a box about the size of an outside air conditioner,” says Moning. The WaterCube can pull over 100 gallons of water out of the air and can be run on solar power.

“Lots of folks in our markets have wells, which can cost $40,000-$80,000 to drill. This machine costs $20,000-$30,000. So, while that’s expensive, if it’s going to answer all of your water needs without having to be connected to the water system, that’s interesting.” He sees it potentially tying in with a developing trend of young people, unable to afford homes at current prices and interest rates, opting for remote work from RVs.

It’s probably fun to fantasize about how millions of young people will start living in RVs and then line up to buy WaterCube, and U.S. Bank will be ready to finance them because it spotted that trend before its peers. Figuring out if U.S. Bank has any unique data or applications that could be monetized with new client segments is much harder. But that is the only innovation that matters.

The Persistent Myth of the Digital Revolution Despite Mounting Evidence

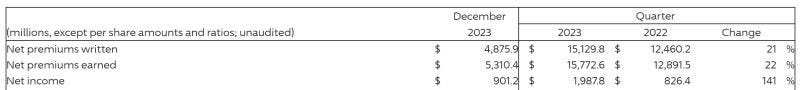

15 months after the launch, Amazon recently confirmed that it is shutting down its Insurance Store in the UK, which was meant to disrupt how consumers buy home insurance. Leading insurtechs are not doing much better, remaining at 90-99% of their stock highs. On the other hand, Progressive Insurance just announced over 20% growth in top-line performance and over 140% in profit:

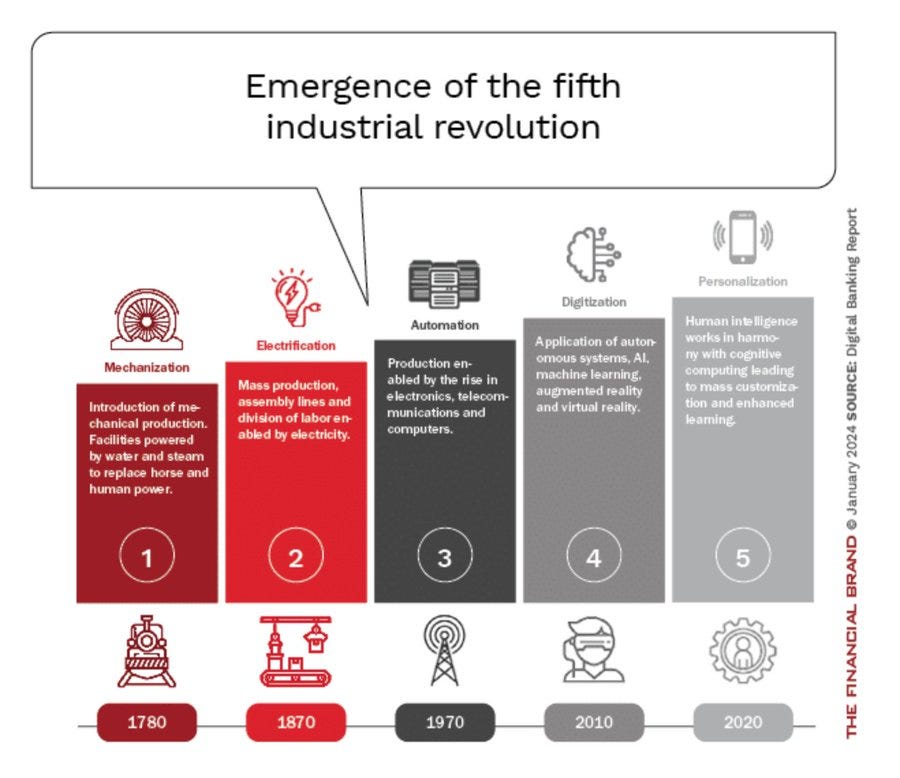

One would think that a steady drip of similar news would assuage even the most intense digital fans, indicating that there is no revolutionary change occurring in financial services and insurance. But no. Similar to PayPal’s characterization of faster checkout as revolutionary in 2024, there is evidently an entire framework describing not one, but two digital revolutions that have already commenced in the 21st century:

In reality, the change is gradual, even in the most digitally-friendly products such as payments. During my recent trips to Stockholm and Mexico City, it was fascinating to observe the differences in consumer preferences and provider offerings. For example, in a top museum in each respective country, one requests digital payment, while the other does not accept any:

In Mexico City, locals enjoy a sense of community gathering around tacos or sweets carts and are not bothered by the lack of digital payment options. The absence of consumer demand is evident in other payment categories. For example, banks' ATMs and exchange shops charge around 10% in fees and markups, making Mexico perhaps the only country in the world where exchanging money at the airport is more economical.

The digital transformation will undoubtedly reach countries like Mexico and the Philippines. Fintech executives from more advanced economies have been relocating there to launch startups in financial services and insurance. Global fintechs are prioritizing their expansion plans in those markets. And, of course, incumbent FSIs will be investing millions in digital initiatives. However, the change in consumer and business behavior won’t be swift because the technology is not perceived as revolutionary.

I encountered this phenomenon with my cross-border startup, SaveOnSend, a decade ago. When approaching migrants from Mexico and the Philippines, they cared little about saving time and money with digital technology and preferred human interaction with cash-based agents.

The change in consumer and business demand for digital innovation could take a decade or even longer. In 2006, a New York subway authority piloted a card payment system with MasterCard and Citi for ride fares that required only a tap at the turnstile entry. That seemed revolutionary to me and some of my friends at the time. We obtained those cards and enjoyed the experience. However, other consumers didn’t care, so the pilot was canceled, and the technology was only reintroduced a few years ago.

While some digital payment methods, like self-checkouts, are being rolled back due to theft, experimentation will continue. For example, Amazon has been rolling out palm payment across its grocery stores. But how many consumers would be excited to use it instead of their current preferred method?

Like progressive voters in politics, there is a significant portion of FSI executives and digital experts who believe that consumers are eager to embrace fundamentally new types of products. However, revolutions are rare precisely because they don’t occur solely due to popular adoption (uprising); they often require dictators and military coercion. Governments in Sweden, India, Russia, and elsewhere implemented specific mandates to expand digital adoption, and coercion worked, not because the technology itself was revolutionary.

Outside of government pressure, personalization and digitization do not feel revolutionary to the average consumer and business because those capabilities are a continuation of the gradual evolution stemming from the automation revolution of the 1970s. But what would the next technological revolution be like? Well, when AGI becomes a reality by 2070, it will likely impact every consumer and business, and the effects of that uprising would be too evident to debate.