Is Your FSI R&D Group an Innovation Theatre, an Operational Mistake, or Moonshot Ready?

Innovation Theatre vs. Real R&D, Fidelity Labs Case Study, Purpose of R&D, Embedding Innovation into Core, Lessons from IBM's Watson Failure, Differentiation-Talent-Focus, Perverse Incentives

Is Your FSI R&D Group an Innovation Theatre, an Operational Mistake, or Moonshot Ready?

"Our involvement stops at the end of the pilot, and it is up to a business unit to scale it," explained the head of Labs for a $5 billion revenue insurance company. I asked if business units request those pilots and engage during them - "No, we prioritize use cases and do all the work." The situation was reminiscent of a typical "R&D group" in a large financial services or insurance firm, but the leader seemed hands-on and sharp, so I had to ask, "Can you ballpark how much money your pilots made in production last year?" He shook his head.

After two decades of experimenting with R&D-type groups, many FSIs have realized that the true purpose of creating breakthrough solutions is virtually unattainable. Consequently, they programmatically shut down those teams or minimized them for innovation theater. In such cases, an FSI would retain 5-10 brainiac employees in a separate location and allow them to tinker away without any expectation of P&L impact. Yes, this means burning a few million dollars annually, but the work is leveraged for content to enhance the perception of a techy coolness factor with prospective investors, partners, and job candidates.

A few larger FSIs, typically above $20 billion in revenues, continue to take R&D seriously. In another newsletter, we discussed how some of those FSIs went overboard with R&D efforts, investing tens, sometimes even hundreds of millions of dollars in setting up such groups in Googlesque buildings and partnering with accelerators. The expectation was that these innovation activities would generate a kind of magical osmosis capable of imbuing employees with the spirit of innovation. MetLife has been my favorite example of such wasteful spending.

A more insightful scenario unfolds when digitally savvy FSIs, like Capital One and Fidelity, seek to emulate startup playbooks to scale and monetize their R&D pilots, transforming them into distinct businesses. Why have they struggled to generate meaningful value after two decades, and what lessons can they draw from both successful endeavors and failures, such as IBM's Watson?

Fidelity Labs: When the Innovation Playbook Meets Reality

Fidelity was already profiled in another newsletter for its overindexing on top-down Agile processes at the expense of driving business impact. Being huge fans of management consultants, Fidelity C-Suite embraced their advice for more efficient processes and hired an army of Scrum Masters and Squad Leaders who mostly act as 20th-century project managers. Coincidentally, Fidelity’s institutional business has fallen from the top spot 15 years ago to the 4th place, far behind the current leaders.

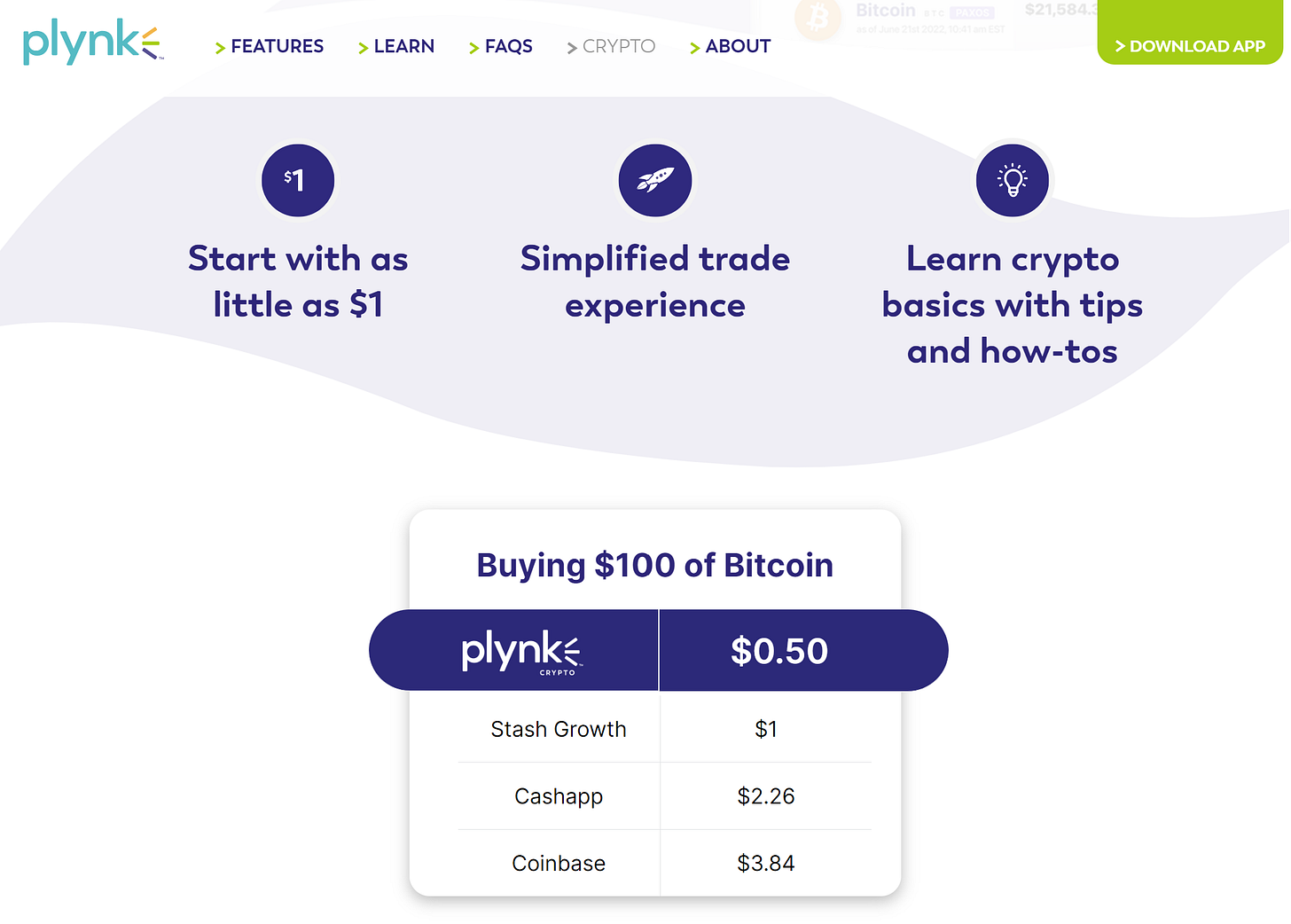

Even for its successful consumer business, Fidelity’s enterprise leadership decided to launch a separate brand, Plynk, to attract younger consumers, including with crypto coins. The fintech subsidiary was launched in 2021 and staffed with Fidelity employees when there was already a graveyard of similar attempts by other top FSIs.

How will Plynk generate a visible impact for Fidelity's more than $10 trillion in assets and $25 billion in revenues? Apparently, by attracting consumers with a few dollars to start and charging less than a dollar per trade while competing with segment leaders like Cash App and Coinbase.

As one of the global leaders in asset management with one of the most advanced digital maturity, Fidelity understandably desires to be an innovation leader among incumbents. The main question is whether its approach to innovation has been working.

To solidify its innovation leadership role Fidelity founded Labs in 2005 with the idea to accelerate the development of new digital capabilities. Unlike some of its asset management peers, Fidelity considered this R&D group not as an innovation theatre but as a serious effort with 90 employees and an annual budget in the tens of millions of dollars.

In almost two decades, Fidelity Labs has created five businesses, with the most prominent one being Saifr. Leveraging its experience with compliance reviews of marketing content, Saifr trained natural language processing models to flag issues and offer alternative wording. Saifr's tooling also enables collaboration between Marketing and Compliance staff to speed up the review process.

In a recent podcast, Fidelity Labs' head, Vall Herard, described Saifr’s operating model and qualitative benefits but didn’t clarify how much Saifr has saved Fidelity’s Compliance and Marketing departments so far. Vall also didn’t explain why Saifr needed to be spun off as a separate business and couldn’t just be kept internally within a Compliance group.

The reason for such glaring omissions is that Saifr is tackling a minor use case, and Fidelity hasn’t yet mastered how to embed innovation in its core business and functions.

What Is the Purpose of R&D Groups in Top FSIs?

Fidelity Labs prioritized Compliance use cases to such a degree that its head even noted, "I joke all the time that we have enough compliance people in an organization to actually start a compliance department." Successful pursuit of use cases does require talent density in that domain, and Compliance is a fruitful area on the surface. In some FSI products like consumer cross-border money transfers, Compliance-related staff could reach 20% of all employees. But Fidelity is not Western Union, and it is not pursuing Compliance use cases related to financial crimes anyway.

Outside of Compliance, a moonshot opportunity for R&D could be a platform and/or structured data that prevents cyberattacks. For larger financial institutions in the US, reported cyberattacks and data breaches have almost doubled in 2023 when compared to 2022, from nearly 8% to 16%, costing them more than a billion in losses. Besides, some cybersecurity incidents require a lockdown of core business, as recently happened with Fidelity National Financial. How much importance would FSIs attach to avoiding substantial financial losses, client attrition, and potential lawsuits? Much more than automating compliance review of marketing content.

Fidelity's approach to R&D appears as perplexing as Capital One’s, with the latter's R&D business addressing similarly trivial use cases, primarily centered around a generic spend management tool for a particular Cloud vendor solution (Snowflake). The R&D businesses in Fidelity and Capital One illustrate a typical disconnect between the purpose of R&D in many advanced FSIs vs. its business impact. Success is usually measured as a testing ground for innovative processes rather than by how much extra percentage this group added to the FSI’s overall P&L.

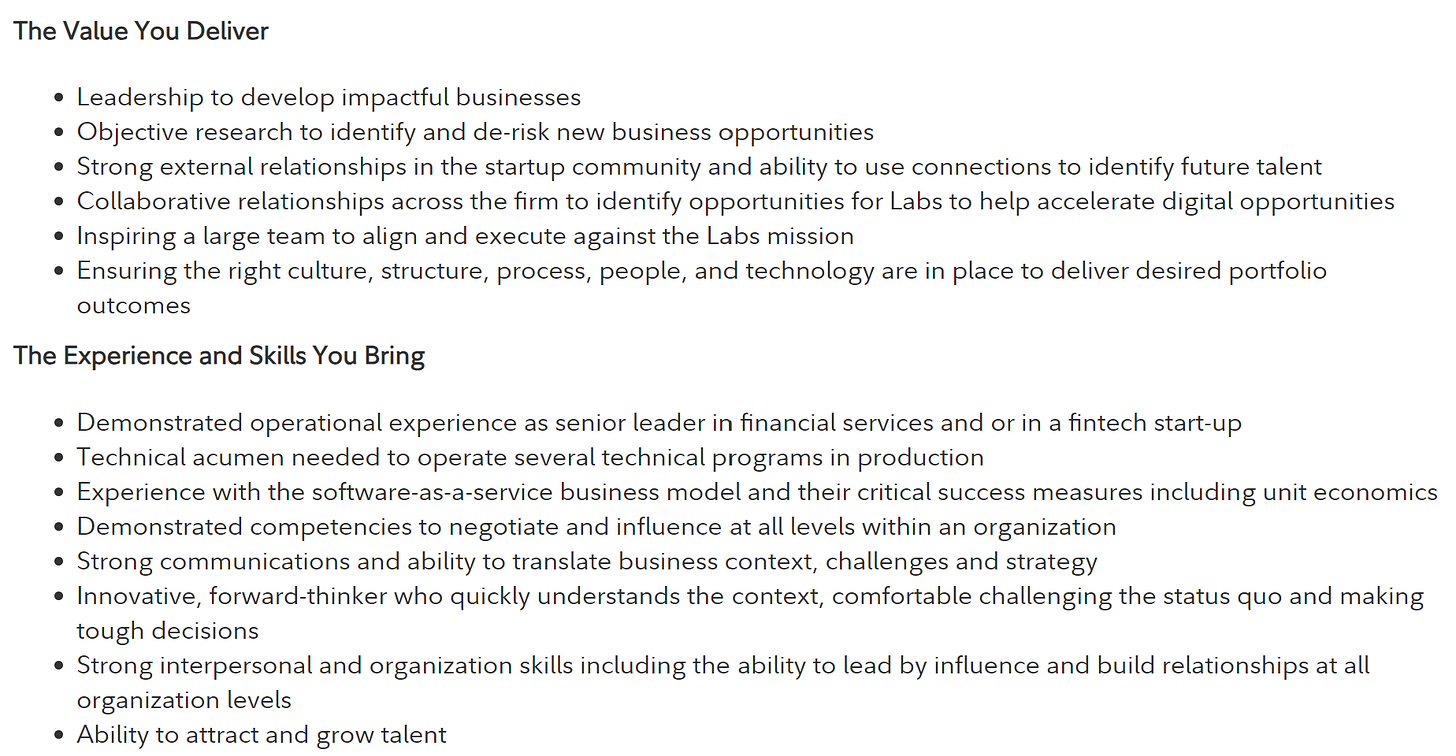

Coincidentally, Fidelity has opened a search for a new head of its Labs - notice what is missing in the role's expected value or desired experience: a track record of significant revenue generation.

If your FSI could afford 100 people working on random stuff, why not swing for the fences with one product that could generate $100+ million in revenues in 10 years? For example, Bridgewater Associates is now attempting a separate AI-based fund. There is warranted skepticism about whether it could work, but at least the firm is taking a shot adjacent to its core capabilities and aiming to generate a significant uptick in its core business. And it makes sense for Bridgewater Associates to have a separate team for such a purpose. Seeding it within regular business and function would be a lose-lose: a distraction for BAU and a slower velocity for the R&D team.

And if an FSI can’t come up with an idea for a moonshot? There is nothing wrong with a Compliance solution for reviewing marketing content per se. But if the best machine learning minds of Fidelity are working on that for years and it saves Fidelity a couple of FTEs, that tool should be built as part of BAU and definitely not attempted to be monetized externally.

Embedding Innovation in Core Businesses and Functions

Perhaps in 2005, when its Labs was founded, Fidelity's core business and functions were too complacent to embrace change and needed an external jolt to start moving. Nowadays, a separate accelerator unit is no longer necessary in leading FSIs. Unless the use case relies on some unproven technology or is intended for an entirely new product, leading FSIs like Fidelity and Capital One are better off embedding innovative capabilities within their core functions such as Product Management, Data & Analytics, and Engineering.

In the case of the Safir solution in Fidelity Labs, its capabilities should be embedded in three core functions:

Automating Compliance-related processes → Compliance function

Helping LOBs/Functions to launch AI use cases → Data & Analytics function

Helping LOBs/Functions to become more Agile → Product Management/Agile function.

As with any shared capability, the R&D group's aim is to make itself redundant by continuously transferring its innovation capabilities and capacity to core business groups and functions while tackling new breakthrough use cases. In the target state, those groups are as effective at scaling innovation as the R&D group.

Pivoting the vision for R&D is a challenging decision in the typical political environment of FSIs. For example, in Fidelity, Labs reports into Enterprise Business Services, which also includes business development and internal consulting groups. Changing Fidelity Labs' mandate to embed innovation capabilities or novel technologies into business lines and functions while focusing on a single moonshot opportunity is likely to uncover three issues:

Lack of demand for innovation use cases in business groups and functions

Concerns with Labs' comparative capabilities in driving innovation.

No moonshot ideas on the Labs' leadership team

Unless the CEO initiates this discussion, other senior executives are unlikely to open such a can of worms.

Lessons from IBM’s Watson failure

The absence of R&D success stories among well-funded leading FSIs illustrates the challenge of getting this capability right. The problem becomes even more striking when considering the case of IBM's Watson.

With a decade head-start on OpenAI in a similar space, IBM had an exceptional AI pedigree, including Deep Blue's success in chess and a victory on Jeopardy! in 2011. Yet, today, IBM’s Watson is off the radar, while OpenAI is valued at $86 billion, which happens to be around 60% of IBM’s overall value. Why has IBM failed to capitalize on its first-mover advantage in AI?

It wasn't due to a shortage of funding or a lack of a moonshot vision. Similarly to OpenAI spending up to half of a billion dollars annually, IBM launched Watson with a $1 billion investment and aimed to change the world, as described in its 2013 Annual Report:

Earlier this year we launched the IBM Watson Group. It will comprise of 2,000 professionals, a $1 billion investment and an ecosystem of partners and developers that we expect to scale rapidly. In the process, we believe Watson will change the nature of computing, as it is already beginning to change the practice of healthcare, retail, travel, banking and more.

Anatoli Olkhovets, who led Watson’s product management team during that time focused on building industry-specific solutions in Financial Services and Healthcare, described to me in a recent discussion a promising beginning for Watson:

‘Watson was heavily driven by the CEO with massive financial aspirations. Compared to my experience in core products groups, we probably moved at 3x speed with setting up a team and pushing releases out.’

However, the main difference vs. OpenAI was the lack of sufficient differentiation to justify such rapid scaling and a lack of focus on a specific moonshot. Only winning a quiz show, IBM Watson was suddenly trying to transform multiple industries. The lack of focus and short-term impact expectations drove the wrong incentives:

‘There was no organizational patience for focused multi-year iteration. Almost immediately, Watson was signed up for a few multi-million deals with the expectation of developing those solutions from scratch in time for delivery, not because we had successfully tackled those use cases on a smaller scale. As an example, for one client, Watson tried to literally cure cancer while the only proven capability was a tool automating patient case summaries.’

By 2017, as clients realized the lack of value, the agreements started imploding, and Watson became another case of overhyped technology:

Compared with IBM Watson's failure, OpenAI is not fundamentally different from other breakthrough successes of the 21st century: SpaceX, Tesla, Amazon, Netflix, Spotify, and others. Not only does the vision have to be monumental, but there are three common components in how to achieve it:

R&D differentiation: platform or data

Talent density: technically superb and not corporate

Focus: one moonshot with a decade-long horizon

R&D’s Differentiation: Platform or Data

Google used search data to build individual profiles with demographics and interests, which served as the catalyst for its ads targeting business, whose revenue is now above $200 billion. As Amazon was building its e-commerce business, it became better than others at managing its data storage and compute capabilities via open APIs, which served as a natural catalyst to start the AWS business, whose revenue is approaching $100 billion per year. Within the financial services and insurance industries, BlackRock built a uniquely capable core platform, which served as the catalyst to start the Aladdin business, whose revenue surpassed $1 billion in 2020.

For this reason, non-theatric R&D groups only make sense in a top FSI, whether it is a specialty insurer, asset manager, or payments firm. Otherwise, a company wouldn’t have a proven differentiation in its internal platform or the amount of data (if it did, it would be among the top in that niche). If an FSI does attempt monetizing Compliance or Procurement or other non-core capabilities, it is essential to address the question of why a specialized vendor, a large competitor, or a disruptor can't do it better.

R&D’s Talent is Unlike Any Other

In my experience, even advanced FSIs like Capital One and Fidelity mostly employ two types of employees in their R&D groups - either corporate types who mastered upward management without generating striking results or technology product experts who don’t have a commercial mindset. This is in contrast to the ideal talent profile who straddles commercial and product mindset with a track record of scaling $100 million revenue technology businesses from scratch.

A follow-up consequence is R&D groups hiring too many people instead of fewer 10X employees. Akin to the best fintechs, the head of the R&D group must be an incredible entrepreneur, but the first 10 employees must also be top players in their roles when compared to leading digital natives and fintechs. This means that FSIs like Capital One and Fidelity need to pick literally the best 10 employees from their companies or hire someone even stronger.

The obvious challenge is that the ideal talent type prefers proverbial Silicon Valley to working in FSI, and the head of R&D often doesn’t have enough political support to poach the very best employees across the firm. But without top talent, it is better not to take R&D efforts seriously then - quality vs. quantity is the key.

The final piece of the talent puzzle is the overall culture of maniacal brainiacs who love to build things at the expense of work/life balance. An FSI should provide them with sleeping cots and unlimited energy drinks and snacks while maintaining its corporate oversight from a far distance.

R&D’s Necessary Success Factor: Focus

There is a very popular pseudo-scientific genre of literature that attempts to prove that IQ is not crucial for success. Bestsellers like “Think Again,” “Grit,” and “Mindset” offer hope that people can achieve anything regardless of their cognitive abilities and that talent mostly correlates with learned habits. The irony about all those books is that they never consider studying the IQs of successful people during their high teens to find any founders or executives with lower intelligence.

Many FSIs follow a similar wishful thinking when it comes to R&D groups. They identify various sufficient practices to drive innovation, except the necessary one: focus. What IQ is to humans, the focus is on the success of innovation. However, because it goes against the human preference for variety and surface learning, FSI executives often prefer a kitchen-sink approach of launching multiple trivial use cases.

The same lack of focus is also the reason why, despite billions of VC funding, even the best startups have failed to disrupt incumbents, as aptly summarized by Russell Higginbotham FCII, CEO of Swiss Re Solutions in a recent interview:

‘Some years back, we used to talk a lot about disruption, and some of the big well known names coming in and disrupting the industry and eating our lunch. I don't think it's happened in that same way because those so-called disruptors have become partners and helped the insurance industry become a more digital modern business. In that sense, we've disrupted ourselves from within.’

Remember from another newsletter how long it took BlackRock Aladdin to start generating millions of dollars in revenue: 6 years from deploying the internal core platform to deciding to monetize it externally, and in the first 4 years, Aladdin only signed up six clients. As the joke goes, BlackRock Aladdin is the overnight success two decades in the making.

For an R&D group in an FSI, the focus is even more crucial than for a startup because the value needs to be visible on top of the already successful franchise. If insurtech or fintech gets to $100 million in a stable and profitable business in a decade, its VCs won’t be happy but will probably make their money back. $100 million in additional revenue for an FSI already generating $5-50 billion only makes sense if the venture is still rapidly growing at that point.

In Conclusion: Mo Money Mo Problems

In conclusion, let’s be honest about the main root cause for R&D groups launching unremarkable businesses and duplicating capabilities with core functions. Some FSIs generate so much cash that they don’t feel like over-optimizing how to spend it. MetLife and Capital One generated $13 billion in free cash flow in 2022, and Fidelity is not far behind.

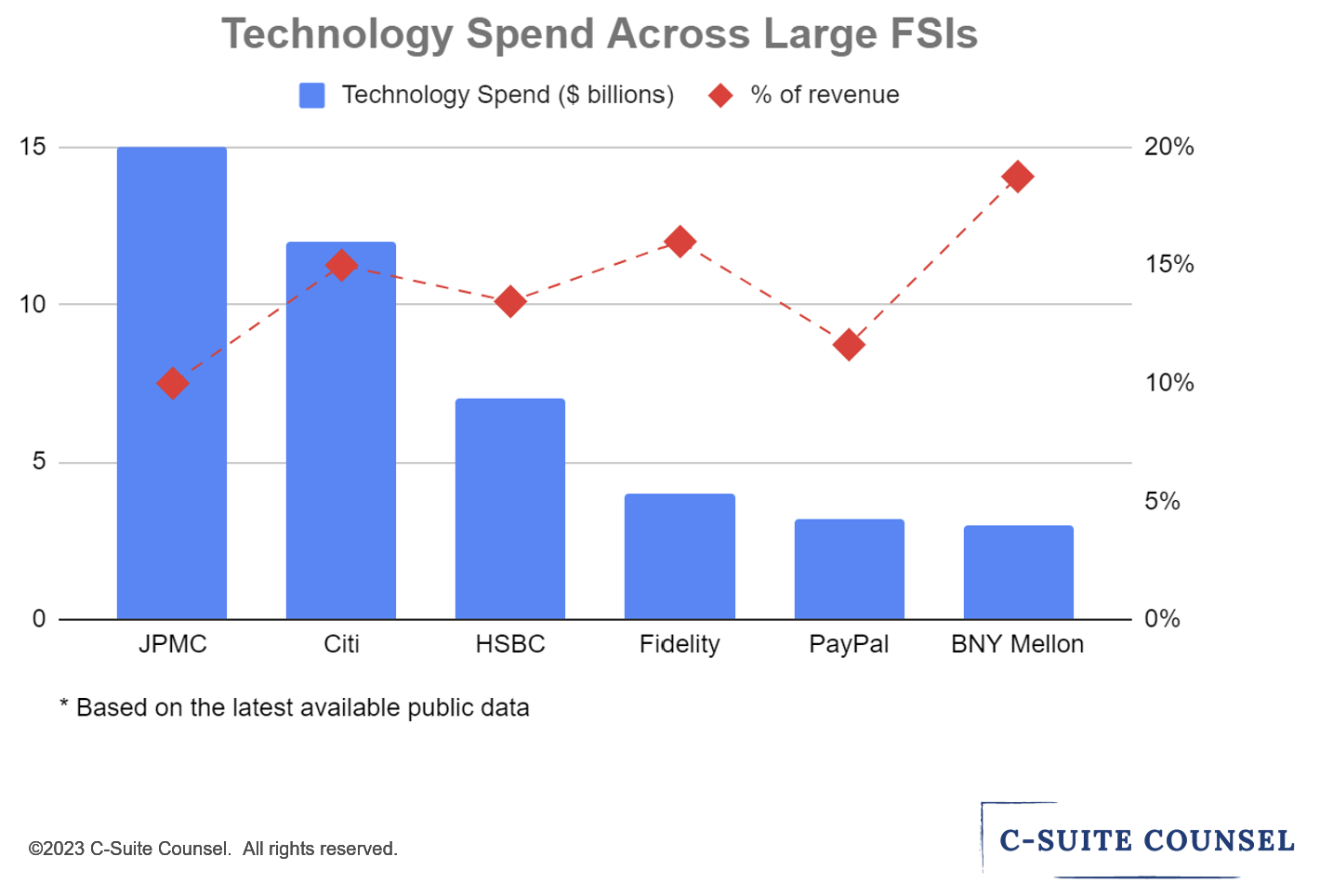

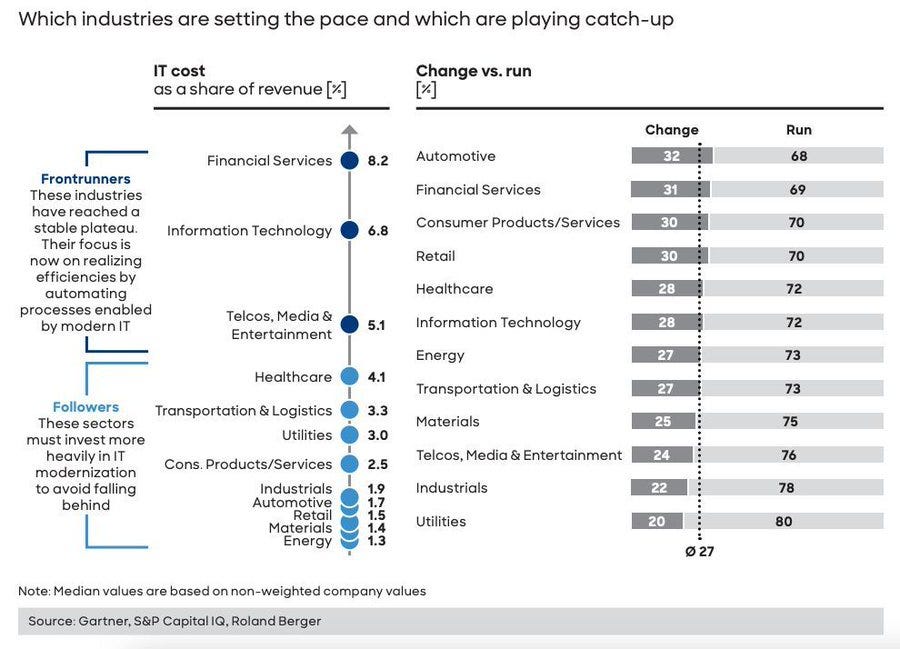

The technology spending arms race also contributed to expenditures in financial services reaching unprecedented levels. A fresh Roland Berger report highlighted FSIs being by far the highest spenders on IT, with an average above 8% as a portion of revenues:

As larger FSIs spend billions on technology, with some like Fidelity well above averages as a percentage of revenue, it is not surprising that a suboptimal investment of less than $50 million annually into R&D doesn't raise red flags.

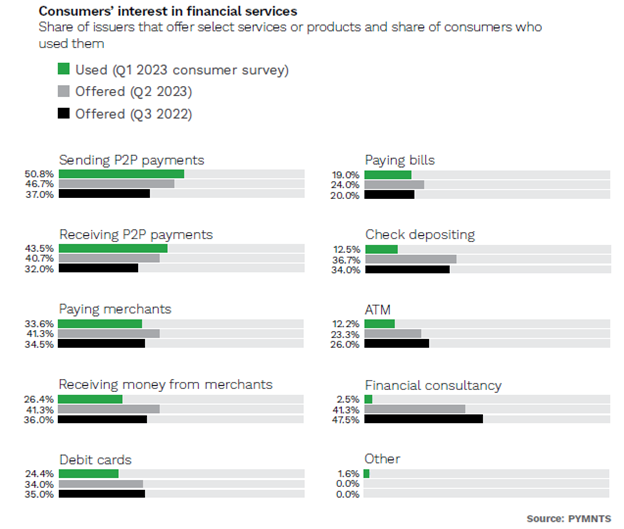

Abundance of funding creates more problems than value because FSIs are becoming better at launching products rather than focusing on their usage and monetization. Even supposedly more effective fintechs are not immune to this issue. As evidenced in the recent research by PYMNTS, fintechs often deploy an excessive amount of features because they can not due to consumer demand.

Congratulations if your FSI has so much money that it could keep launching marginal products. But if an FSI wants to instill a culture among employees of treating the company’s money as its own, the next step is to acknowledge whether the main purpose for the R&D group is innovation theatre or a moonshot impact - and proceed accordingly.