Can Incumbent FSIs Keep Growing Stronger While Startups Gain Market Share?

Also in this issue - The Achilles Heel of Digital Transformation in FSIs: Rising Fraud

Can Incumbent FSIs Keep Growing Stronger While Startups Gain Market Share?

“Our head of embedded finance promised the C-suite $100+ million in revenues, so he was permitted to spend $50 million and hire 500 people. After securing just one client within a year, his team was cut down to 50,” explained an executive from a top-4 US bank. His story didn’t surprise me because of the upfront waste, but because of how quickly the incumbent adjusted its ambitions. The decision was also unusually nuanced—rather than terminating the entire unit and its executive, the effort was right-sized for more accurate returns.

Incumbents are not just becoming more agile; some are becoming indistinguishable from leading fintechs in their technology models. One of the top US banks has consolidated its 10 payment applications into a single platform over the last 5 years using best-in-class tooling. Although the effort I observed exceeded the original budget and timeline, the bank is now positioned to support frequent product releases, constrained only by budget approval.

Furthermore, some exceptional incumbents have been ahead of their industry, including startups, across digital pillars for decades. Progressive Insurance’s superiority in UX and data analytics resulted in more than doubling its market share in the US consumer auto insurance market between 2008 and 2023. This is in stark contrast to the top incumbent, State Farm, with unchanged market share, or the downfall of other players like Nationwide, whose share dropped from 4.6% to 1.7% during the same 15 years:

Elevated digital capabilities by Progressive and other leading incumbents have denied share growth not only to their traditional peers but also to insurtechs. For example, 9 years after its founding, a leading U.S. insurtech, Lemonade, is still 140 times smaller than Progressive, and in the latest quarter, its net profit margin was -47% compared to Progressive’s +8%.

However, what truly highlights the lack of Lemonade’s competitive differentiation is that both firms grew at the same rate. In a recent exchange with Lemonade's CEO, Daniel Schreiber, a Yahoo Finance reporter pointed out that the stock dropped 15% on lower Q2 profits. In response, the CEO began by declaring the quarter was "spectacular on every metric that matters," and continued to repeat the same generic list of supposed advantages of a startup over incumbents.

To be fair to consumer insurtechs like Lemonade, their founders couldn’t have predicted a decade ago that they were trying to disrupt some of the world’s toughest markets. And not just due to superb digital incumbents like Progressive, but also because some of the industry segments have been losing billions for the last several years:

In profitable FSI verticals, the competitive dynamic is more nuanced. While fintechs haven’t disrupted banking or money management incumbents, they have become a staple for consumers and small businesses. It appears that consumer banking in financially advanced countries has reached a new stable state: both primary attrition and neobank-only usage are below 10%, while consumers, on average, use 2-3 providers (a traditional bank as primary and 1-2 fintechs for accessory services, as Ron Shevlin calls them).

A large portion of fintechs founded in the 2010-2015 cycle are now profitable while continuing to grow at around 20% with billions in annual revenue. Even players like SoFi, with some product lines in the tough below-prime lending segment, have admirably managed to stabilize both revenue growth and profit margins:

Among leading fintechs, Q2 earnings marked a major milestone. Cash App has become a top-10 consumer bank by revenue in the U.S. Without including its business volume or bitcoin revenue, Cash App surpassed the revenues of BMO U.S.'s Personal Bank. If it maintains its recently stabilized growth rate of around 20%, Cash App could move up each subsequent spot in the rankings every 3-4 years, with TD’s U.S. Retail Bank being the next to be surpassed.

The true shift in leadership has been unfolding in the area I have followed most closely over the past decade: consumer cross-border money transfers. Although disruption has been gradual rather than rapid, the remittance giant Western Union is steadily ceding market share under pressure from fintechs:

Across all C2C cross-border use cases, Wise emerged as the global leader in 2022, just 11 years after its founding. In the U.S., Western Union still leads in volumes, but Remitly, also founded in 2011, is rapidly catching up, with Wise close behind. Among the top-4 banks, only JPMorgan Chase remains in the top-3, but likely not for long:

What makes digital transformation in FSIs so fascinating is the impossibility of generalizing trends across products and regions. An incumbent might experience significant market share growth in one area, while a fintech achieves the same in another. FSI executives need to understand which competitor is leveraging digital capabilities most effectively. The biggest market share gainer over the last decade likely holds the answer. Emulating their business, operating, and technology models represents the optimal digital transformation strategy.

The Achilles Heel of Digital Transformation in FSIs: Rising Fraud

“Every time we launch a new online channel or product, we shoot the first three applicants,” half-jokingly explained the head of retail for a top-10 Russian bank. It was then, in 2013, that I first realized the digital revolution in financial services and insurance has an ugly counterpart: fraud. The arms race between the FSI industry and fraud syndicates seeking any opening to exploit was still in its early stages.

In 2015, we were helping a small bank in the Midwest to jump-start its stalled growth. Before the engagement began, I asked colleagues to apply online for the bank’s checking account. Four out of seven applications were rejected. The bank explained that these unprecedented restrictions were due to excessive fraud levels and an inability to eliminate false negatives. A couple of years later, that bank was shut down.

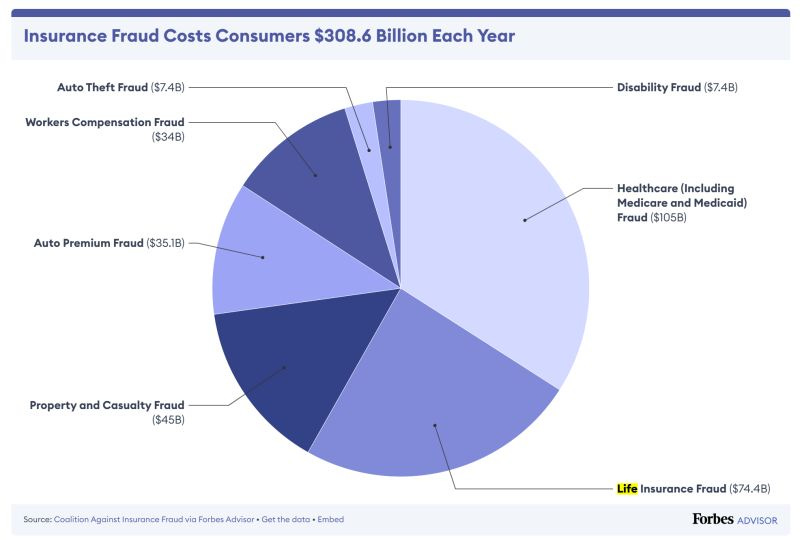

By now, even in traditionally less digitally advanced sectors like life insurance, fraud levels have surged, costing each industry vertical tens of billions annually in the U.S. alone:

Online fraud rates are growing across multiple vectors, partly driven by novel technologies like deepfakes and GenAI-based scripts. A friend of mine, an FSI executive, received a blackmail pop-up when viewing one of his asset management accounts. Threatened with the ruin of his life, he panicked and called his bank to wire $50K. Despite the bank's suspicion of fraud and efforts to talk him out of the transfer, he insisted. Once calmed, he realized it was a bluff, but the transfer had already been completed.

Skillful scam artists and enterprises can expand their reach and leverage their extensive experience in overcoming victims' defenses by using technology to instill fear of being falsely implicated in actions they did not commit. Scaring someone with deepfakes can induce emotional states that override logical thinking. As Kathy Stokes, AARP's director of fraud prevention programs, puts it, "Scammers call it getting the victim under the ether." This is why so many intelligent individuals fall victim to scams—not due to a lack of IQ, but because scammers expertly manipulate emotional responses.

While advancements in data and analytics help leading incumbents and startups slow down or even decrease fraud levels, these tools have limited power against first-party (aka friendly) fraud. Due to the lack of legal consequences, consumers have little downside in lying about unauthorized purchases or payments or when applying for loans or mortgages.

Rather than allocating more resources to imprison consumers committing fraud, the government is targeting FSIs. Financial services and insurance companies often have detailed statistical data showing that certain ethnic groups consistently commit higher levels of fraud for specific products and in particular zip codes. For instance, Armenians in LA are so notorious that stand-up comedian Andrew Schulz referred to them as “the greatest scam artists in America” in a recent special. However, FSIs are not permitted to use digital tools to decline these customers at higher rates or to subject them to manual reviews.

What is even worse, governments are increasingly trying to make FSIs responsible for consumer behavior. In a recent filing, JPMorgan Chase disclosed increased pressure to resolve fraudulent transfers via Zelle:

“Government Inquiries Related to the Zelle Network. JPMorgan Chase is responding to inquiries from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) regarding the transfers of funds through the Zelle Network. In connection with this, the CFPB Staff has informed JPMorgan Chase that it is authorized to pursue a resolution of the inquiries or file an enforcement action.”

Regardless of the regulators' approach, traditional FSIs are driven to offer more products and services without human intervention as consumers and businesses migrate online. This highly competitive environment compels companies to provide faster solutions with lower margins. Hemanth Munipalli, CFO of Remitly, the world’s largest C2C cross-border money transfer player by online revenue, recently described this conundrum:

“And I think the important element when you think about the fraud systems that we have is there is a constant balance between optimizing for fraud loss rates and maintaining a great user experience, avoiding what we call higher sideline rates, meaning manual reviews for good customers.”

This excruciating complexity means that fraud capabilities will increasingly separate winners from laggards among FSIs. Whether instigated by crime syndicates or industrious customers, financial services and insurance companies lagging in digital transformation will become more prominent targets for online fraud. While fraud will remain an Achilles' heel of digital transformation, an FSI doesn’t have to view fraud capability as a differentiator but rather as a sufficient measure to deter fraudsters and make them look for easier targets elsewhere.