FSIs Continue to Enjoy Investor Patience for Digital Transformation ROI

Also in this issue: FSI CEOs' Focus on Digital Transformation Could Be Enriched by a PR Touch of Social Responsibility

FSIs Continue to Enjoy Investor Patience for Digital Transformation ROI

In the U.S.'s age of decadence, the value creation of FSIs—the primary yardstick for judging CEO performance—becomes increasingly unclear. The prime examples are crypto ventures that are supposed to reinvent financial services. Just a day after launch, the Trump meme coin's valuation matched Block's, while Ripple's XRP nears Bank of America's market cap. Given that Uber owns no cars, Airbnb no apartments, Alibaba no inventory, and Facebook creates no content, does a blockchain-based company even need revenue to become the world's largest FSI?

Traditional FSIs also share this exuberance, often judged based on long-term potential rather than short-term returns on technology investments. Of course, this is within reason, as long as efficiency stays within a peer range and revenue doesn’t decline too sharply. Citi and Truist’s CEOs learned these limits in 2023, when, after two years of failing to bring efficiency in line with peers, their bank stocks dropped 50-60% from their highs. Tired of waiting for “leading with empathy” or post-merger synergies to drive results, large investors had a "come to Jesus" moment with the CEOs, prompting them to initiate massive cost-cutting efforts.

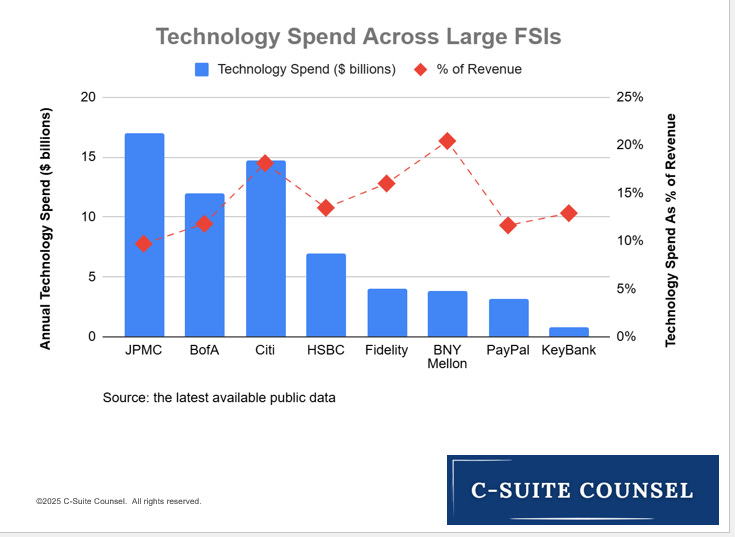

However, most FSIs now benefit from positive expectations and patience in converting digital transformation investments into accelerated revenue or, at the very least, lower-cost operating revenue. Among more prominent players, technology budgets saw a healthy increase this year, reaching fintech-like levels of 10-20% of revenue.

Part of the reason for this patience is quite sensible. Even among the most effective FSIs, generating substantial revenue from novel digital products takes a long time. BlackRock, for instance, spent years building its core platform before it started monetizing under the Aladdin brand. It took further years to secure its first few clients and a quarter of a century to finally surpass $1.5 billion in revenue. While Aladdin remains an unprecedented example of FSI platform monetization success worldwide, its share of total revenue dipped slightly in 2024:

Creating new revenue streams takes considerable time, even for the most successful fintechs. For instance, Wise has become the largest C2C player in cross-border money transfers after a decade of effort. While it has surpassed Western Union and maintains profitable growth at a steady 20%, gradually lowering prices along the way, its newer Platform business tells a different story. After nine years of efforts to scale this segment, its contribution to overall volume remains "very little."

So, it’s not necessarily surprising that it could take Chase at least four years to break even on its digital bank launch in the UK. Surprisingly, despite investing $1-2 billion, Chase already plans to expand into Germany. Here is how JPMorgan Chase’s CFO, Jeremy Barnum, explained this bold strategy when questioned during a recent earnings call:

“… the strategy is very different and it's a very different moment. So, you know, it's a new initiative. It's obviously not risk-free, but it's going pretty well. And, you know -- but pointing out the obvious, if we didn't think it was worth it, we wouldn't be doing it.”

The CFO is typically the last line of financial defense among FSI C-suite executives, tasked with challenging business leaders and the CEO to demonstrate ROI on risky investments related to digital transformation—not acting as a cheerleader who views technology spending as "mandatory."

When specifically questioned about the efficiencies resulting from technology investments, Jeremy Barnum’s response was even more telling. He conflated efficiency with the productivity of software engineers and the launch of new digital products rather than addressing the broader financial impact or cost savings that might stem from these investments:

“… we're putting a lot of effort into improving the sort of ability of our software engineers to be productive as they do development. And there's been a lot of focus on that, the development environment for them in order to enable them to be more productive. And so, all else equal, that generates a little bit of efficiency. We also have a lot of focus on the efficiency of our hardware utilization…

… we had probably reached peak modernization spend… at the margin, that means that inside the tech teams, there's a little bit of capacity that gets freed up to focus on features and new product development and so on, which is also, in some sense, a form of efficiency…”

Such confusing responses highlight the likely lack of visibility into ROI, a common issue among FSIs. While Cash App is growing at 20%, Chase faces stagnant revenue and declining profits. In this context, allocating 10% of revenue to technology and investing $1-2 billion in European expansion seems either an excessively long-term play or a costly distraction.

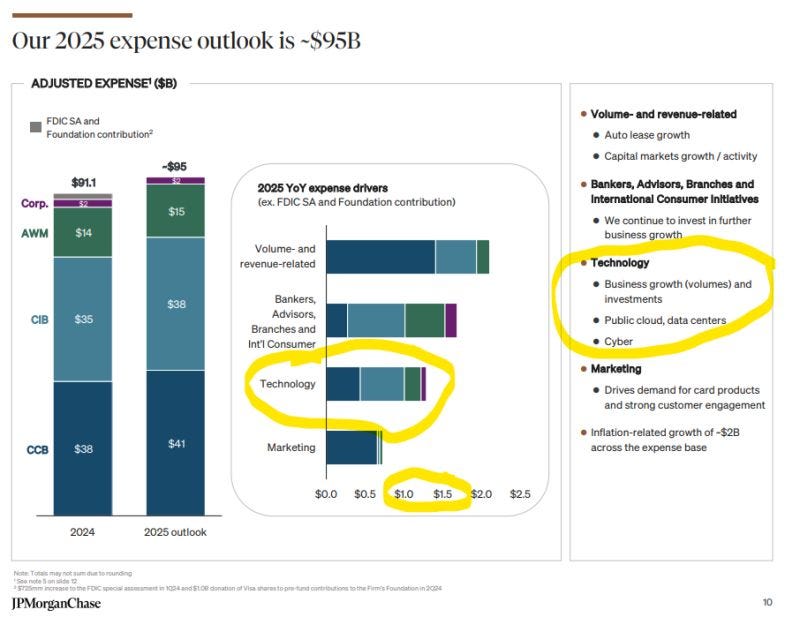

However, in today’s environment, such concerns can be easily overlooked. Already holding the largest FSI technology budget globally, JPMorgan Chase plans to increase expenses by another $1-1.5 billion this year. With past costly tech modernization efforts yielding limited progress in scaling, the IT focus will gradually shift toward enabling top-line impact through new products and features:

This doesn’t mean that such FSIs lack the right digital transformation strategy per se, but rather that they don’t feel the need to apply more rigor in ensuring financial returns. For example, with 20% of revenue spent on technology, BNY is one of the highest among FSIs worldwide and the most explicit in its transformation into a platform business. While its peers typically focus on technology modernization for digital transformation, BNY recognizes that a platform-based business model requires a fundamental shift in the operating model:

The gap in such a sensible approach lies in the outcomes. Moving all employees to the target-state model shouldn't be the goal—the key is maximizing effectiveness, not efficiency. Transitioning 20-40% of the organization annually to entirely new ways of working seems more like a PR exercise than a deliberate prioritization that assesses where digital transformation is critical and where traditional silos remain effective.

Moreover, while BNY is correct in considering platform monetization afterward, like BlackRock’s Aladdin, tech platform consolidation becomes a cop-out if it's the primary benefit of such a massive transformation. Consolidation and cost-cutting can be achieved with a 20th-century operating model. The true purpose of digital transformation is to significantly accelerate revenue growth.

This disconnect between digital investments and outcomes becomes especially clear with Bank of America. Its investor presentation includes slides on digital success for each business line. For instance, there has been a steady increase in digital growth and usage in the consumer group. However, how has that impacted the financial performance of that business line? Revenue has grown in line with inflation, and the efficiency ratio has worsened.

The silver lining of such a relaxed attitude is that we witness many big-bang experiments, IT employees play with the latest tools, and customers gain more digital options from traditional FSIs that don’t rush to demand immediate returns. FSIs would be wise to use this time to learn how to estimate ROI if investor patience suddenly runs out. As Atul Verma, former CIO of BMO’s U.S. personal and business banking division, described, here's how to start:

“It will be good to see true value metrics, if any, that are improved by an upward trend on these basic metrics. For example, is digital adoption helping the bank reduce physical service costs or enabling higher-value physical interactions with the customers? What is the quality of the digital sales compared to sales coming from other channels?”

FSI CEOs' Focus on Digital Transformation Could Be Enriched by a PR Touch of Social Responsibility

For a typical FSI CEO, much like a politician, the bar for losing their job is very high. A stagnating jurisdiction, like a stagnating FSI, is usually not enough of a reason for dismissal; it typically requires a disaster. The TD Bank CEO, for example, had to leave on an accelerated schedule only after the bank was forced to pay billions in fines for AML lapses and faced the threat of seeing its assets decline by up to 7% annually if it failed to implement a resolution plan.

In such a safe environment, some CEOs don’t mind taking political risks to drive societal change by leveraging their financial heft. After the death of George Floyd and Biden’s win, the U.S. environment seemed welcoming to such broadly minded CEOs. BlackRock became a textbook example when it started pushing companies to invest in the energy transition, culminating in Exxon losing a proxy fight. BlackRock also began pressuring companies to add minorities to their boards.

It didn’t matter that China was responsible for 95% of new coal power construction or that adding minorities to BlackRock's board didn’t accelerate its financial performance. Having $10+ trillion under management to make even more money seemed too unenlightened.

In retrospect, Larry Fink mistakenly confused the vibes in his circles with the national zeitgeist. The backlash was so severe that BlackRock had to stop interfering with boards and cut back on progressive language in its guidance. Nonetheless, the brand became so strongly associated with prioritizing social change over fiduciary interests that American Airlines recently lost a large lawsuit simply because its retirement plan included BlackRock’s plain-vanilla pension plans.

One might expect other CEOs of large FSIs to learn from this example and refrain from critiquing the behavior of American consumers and companies—and most have. ESG-related topics are now rarely discussed, and Wall Street is exiting the Net-Zero Banking Alliance en masse. As the Financial Times recently reported, there’s even a growing tolerance for the “inclusivity” of differing viewpoints.

Even the way people on Wall Street talk and interact is changing. Bankers and financiers say that Trump’s victory has emboldened those who chafed at “woke doctrine” and felt they had to self-censor or change their language to avoid offending younger colleagues, women, minorities or disabled people.

The learning was so complete that a recent case of an FSI CEO who didn’t get with the program went viral. Tom Wilson at Allstate has continuously positioned himself as an FSI leader driving broad societal change. His bio on the company website proudly checks off every "enlightened" cause:

That would have been fine if CEOs like Tom Wilson postured privately, but for some inexplicable reason, he decided to speak up after a recent terror attack in New Orleans. In a video message, Tom offered condolences before suggesting that Americans should avoid bigotry and move on:

Tom’s speech quickly became an instant meme. It depicted an out-of-touch FSI CEO who couldn’t read the room and appeared to care more about the perpetrators than the victims.

At least with BlackRock, the company is a global leader, even in the most challenging innovations like platform monetization. So, there is some justification for why Larry Fink might get bored after achieving the wildest professional ambitions. In contrast, Allstate's market share in core products like auto insurance hasn’t changed in 15 years. While Geico has increased its market share by half and Progressive has doubled it during that period, Allstate has remained in the 10-11% range between 2008 and 2023:

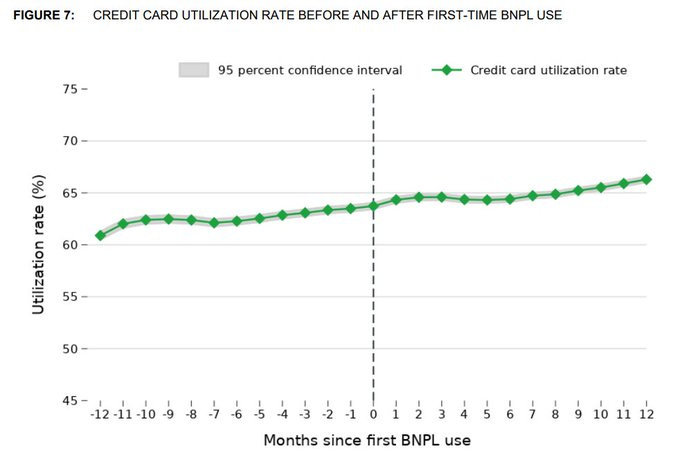

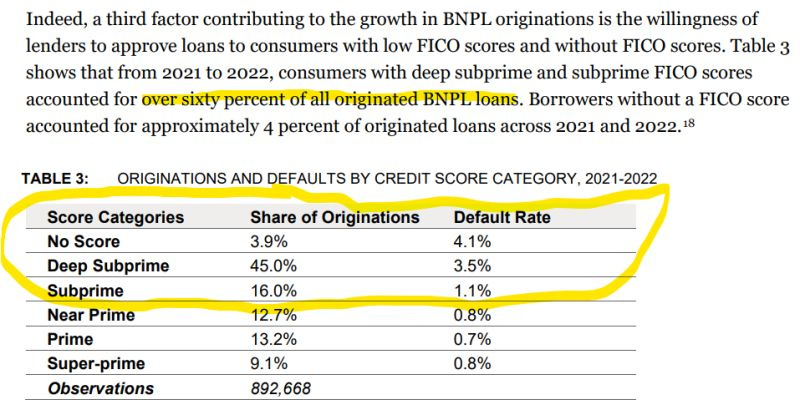

If traditional FSIs need to express their social positions, perhaps to placate talented but agitated employees, they should learn from the leading fintechs how to do so more elegantly. For example, since its launch in 2012, Affirm’s CEO has consistently talked about the dangers of credit cards for consumers and how his BNPL product would eliminate excessive profits of usurious bankers. Yet, despite positioning itself as a credit card killer, Affirm has never shared trending data on its users' credit scores or credit card indebtedness—and will likely never do so, as it would probably reveal a worsening situation, as was directionally indicated in the recent CFPB analysis:

Affirm brought a well-known business model into the U.S., cleverly realizing that by offering small credit to struggling people, they are likely to repay before using a credit card. A recent CFPB study shows that over 60% of BNPL loans go to consumers with below near-prime credit scores. However, positioning the company as empowering financial inclusion gives it a higher calling and helps avoid backlash from the broader population and politicians.

There’s a quaint "useful idiots" myth about Lenin observing Western elites sending large sums to his government just as they ran out of money while trying to conquer the country. The story goes that Lenin realized these well-off, educated Westerners bought into his shaming of exploitation and sought to redeem themselves by funding the Soviet march toward “peace and equality.”

In the current environment, being a useful idiot is still possible, but it’s becoming increasingly risky. Instead, FSI CEOs should dedicate their energy to personally developing digital transformation muscles and demonstrating an apparent acceleration in financial performance. Any social responsibility initiatives could be treated as PR while staying aligned with the periodically shifting political winds.