One FSI’s Disruptor Is Another FSI’s Vendor

Also in this issue: Short-Term ROI Eludes FSIs in the GenAI Race

One FSI’s Disruptor Is Another FSI’s Vendor

Paraphrasing the opening of Tolstoy's Anna Karenina: "Every failing fintech is failing in its own way; successful fintechs are all alike." The most prominent fintech companies growing fast and making money today usually start by focusing on a specific type of client and product. Once they grew quickly and profitably, they began offering related products and expanding into new markets. Eventually, their internal applications become so powerful that they start making money by selling those platforms to their competitors.

They navigate those horizons successfully and rapidly, thanks to an operating model too intricate for traditional FSIs and most fintechs. It combines extreme focus with atomic chaos by design while maximizing in-house buildout. This enables complete control over variable costs, time to market, and UX, allowing them to surpass competitors in unit economics, velocity, and product quality.

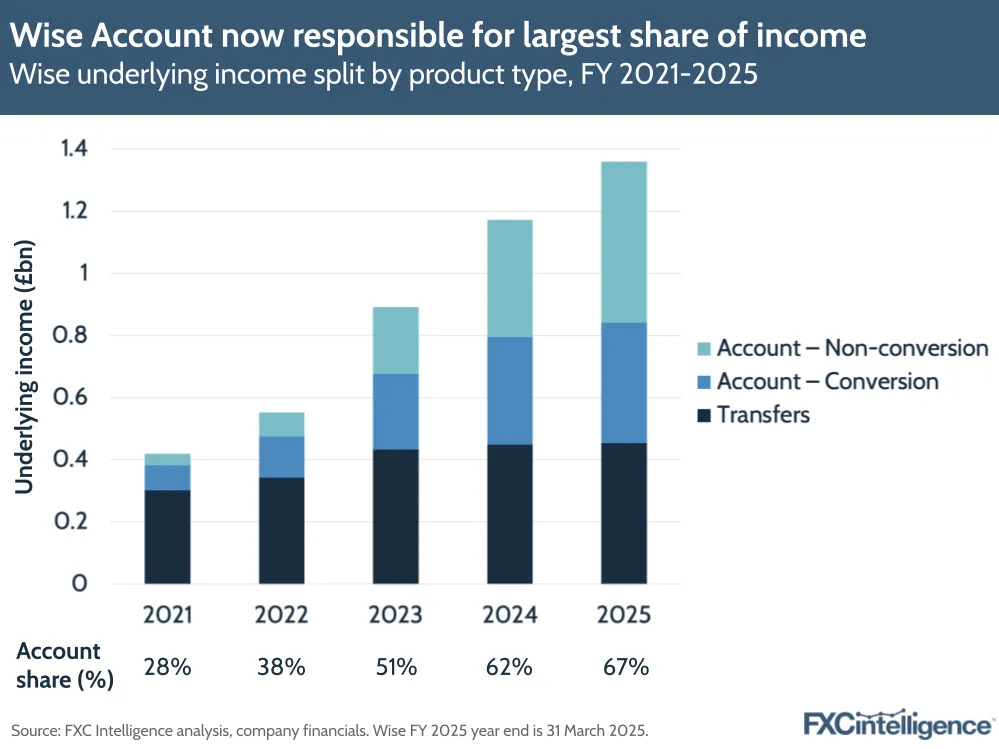

Wise is a canonical example of such textbook scaling. It dedicated its first seven years to money transfers for expats. Then, in 2018, it launched an account product with a debit card. Seven more years on, two-thirds of all Wise customers use that account. More importantly, Wise now generates more revenue from account services than from the original transfer-only product. Even more impressively, the largest revenue contributor is no longer transfers and conversions but card fees, interest, and related streams:

As is the norm with the best fintechs, Wise’s superior value proposition in service quality and pricing drives such high customer satisfaction that users recommend the product to their circles, often without incentives. This allows Wise to sustain a 20% growth rate in volumes without significant marketing spending. As a result, in just over a decade, Wise became the world’s largest international money transfer provider for consumers, offering the lowest overall price while maintaining attractive economics.

Is Wise a disruptor? Not yet in blue-collar remittances, but Wise has captured a leading share in the premium end of C2C flows to some of the most popular destinations. India and the Philippines alone account for over 10% of Wise’s total C2C volume. Wise already moves 5× the C2C cross-border volume of JPMC and 10× that of HSBC—while still growing at 20%. So, the answer seems to be a resounding “yes.”

Not so fast. JPMC’s cross-border transfer volume with consumers grew 3% and BofA’s 7% in 2024. More broadly, in the consumer financial services market—arguably the most targeted by fintechs—top players like Chase have yet to experience any meaningful impact from fintech challengers.

JPMC CEO Jamie Dimon feels so confident in the bank’s long-term potential that he plans to continue massive investments despite turbulent macro conditions, confirming on a recent Q1 earnings call: “The investment that we do in banks, branches, technology, [and] AI is going to continue regardless of the environment.” Let’s also not forget JPMC’s bold digital banking push in Europe and its category-creating blockchain venture, Kinexys.

Notably, Dimon listed branches before technology and AI. A decade ago, digital experts widely predicted major disruption of FSI incumbents, but those forecasts clearly missed the mark. Predictions around the disappearance of branches and human advisors have also proven far off.

However, with several fintechs now reaching the scale of top-20 banks in niche products—and still growing rapidly—the next decade will be a more meaningful test of whether incumbents like Chase can truly preserve their market share. Based on recent quarters, the answer will vary by product. For example, in Q1, core banking and wealth management revenue declined slightly, and overall net income was down nearly 10%.

The most likely future is co-existence between top financial services incumbents and leading fintechs. This will happen in two ways: top incumbents and leading fintechs will continue pushing smaller traditional players and fintechs out of business, and top fintechs will become vendors to incumbent banks for core platforms in niche products.

The latter will only apply to products where incumbents don’t generate significant revenue and can’t match fintechs on product quality. For example, multiple banks have attempted to launch fintech-like competitors to Wise and Remitly in C2C cross-border transfers—BBVA, Santander, and HSBC—all failed. Similarly, after eight years, the highly confident bet of large U.S. banks on building a “Venmo killer” has quietly ended. Meanwhile, Venmo’s total payment volume has surged nearly tenfold.

Not having a great product doesn’t necessarily mean that top traditional FIs will be willing to pay a competitor. Just imagine how exceptional the value proposition and code must be—outperforming in-house builds and top vendor solutions. That’s why BlackRock’s Aladdin remains a unique example, taking a quarter of a century to surpass $1.5 billion in revenue.

Even for BlackRock, Aladdin’s portion of total revenue has only increased by two and a half percent over eight years, and it has even declined recently. This puts into context Wise’s ambition of eventually having the majority of its revenue come from selling the Wise Platform for cross-border transfers to traditional and digital banks.

It took Wise Platform eight years to contribute 4% of the company's overall volume, with some well-known banks signing up for its service. Like BlackRock’s approach with Aladdin two decades ago, Wise is now doubling down on its platform monetization effort by rapidly growing its sales and delivery capacity.

As Wise continues expanding its banking offering to other products, will top banks be comfortable working with such vendors? Or will incumbents see leading fintechs as disruptors who ultimately aim to push them out of other niche products, dismantling their business brick by brick?

Short-Term ROI Eludes FSIs in the GenAI Race

GenAI obviously works. Tens of millions of consumers and workers use it daily. You can even land a coveted job by acing a remote interview with tools like ChatGPT, Final Round AI, and Interview Sidekick. For FSIs, perhaps GenAI can’t tackle client-facing capabilities where precision is crucial, demanding clear, precise data in electronic form. However, back-office automation of manually processed written documents seems ripe for LLM innovation, where absolute certainty is less critical.

Yet, capturing ROI on GenAI investment remains as elusive as two years ago. To gauge GenAI’s impact in large FSIs, consider that Lloyds Bank recently highlighted achievements such as 100 employees building an AI agent pilot. At the same time, 300 leaders were sent to an 80-hour GenAI training to develop an "AI-first" mindset.

As CEOs and CFOs engage in their quarterly song and dance with analysts about being all-in on GenAI, in my conversations with FSIs, everyone seems challenged by how to monetize the supposed unbounded productivity boost. With an unusually confident executive, a typical dialogue goes something like this:

“Yakov, I know that GenAI would be a game-changer because my group uses it daily.”

“Great, have you cut a material number of staff or increased revenues?”

“Not this year.”

How come sales, operations, and IT personnel report much higher productivity, yet it doesn’t seem to translate into revenue growth acceleration or layoffs in those groups? As usual, the answer comes down to the operating model and financial incentives. Who should be accountable for driving straightforward 7-step use case prioritization and scaling afterward, and is that executive financially incentivized to achieve high impact?

Identify Pain Points & Opportunities – Analyze key inefficiencies across business, operations, and IT.

Quantify Value Leakage – Use specific metrics to confirm trends and validate financial impact.

Review Prior Efforts – Assess past initiatives using traditional analytics (AI, Python, SQL) and any existing GenAI pilots.

Determine Optimal GenAI Use Cases – Identify areas where traditional methods fall short and where GenAI can drive significant improvements.

Assess Data Availability - Confirm whether the unit owns sufficient proprietary data and can supplement it with external data as needed.

Industry Benchmarking – Validate that top traditional FSIs and leading disruptors have these use cases in production.

Finalize Priority Use Cases with Expected Impact – Prioritize based on impact (NPV + ROI), feasibility, and strategic alignment.

By typically having IT lead GenAI scaling, FSIs like Goldman Sachs hope that 25% of software engineering employees armed with GenAI tools for faster coding will naturally accelerate earnings growth. However, without business product owners driving these faster-moving engineering teams, a higher velocity is more likely to accelerate the growth of technical debt and unnecessary product features.

In a recent interview with PYMNTs, Belinda Neal, Goldman’s chief operating officer of core engineering, focused on adoption, as is typical for IT executives. But if a business executive isn’t accountable for investments into Neal’s group while the CFO acts as a cheerleader, who exactly is “supercharging 12,000 developers” to make Goldman Sachs money?

Not surprisingly, Goldman Sachs' Q1 earnings didn’t hint at any supercharging results from wholeheartedly embracing GenAI. Revenue was up 6%, while operating expenses increased by 5%. The only bright spot came from the equity trading boom, but Goldman Sachs has been dominating equity trading for roughly four decades—not exactly a result of GenAI-enabled development.

Another main reason for struggling to demonstrate short-term ROI is that decades of technology innovation have made FSIs like Goldman Sachs highly effective. How much room is left for GenAI upside for large traditional FSIs and fintechs that have mastered Machine Learning over the previous decade?

For example, Wise leverages ML across its enterprise capabilities, including Marketing. While piloting, scaling, and alternating messages and incentives across numerous channels, its ML-based engine can predict with 96% accuracy the eventual LTV of incoming customers and determine if the cost per acquisition is worth it. Will GenAI push that to 98% accuracy, and what would the ROI be on that tiny lift?

Many FSI executives view the commonsensical establishment of a clear operating model, prioritization of use cases, and selective scaling as too risky for their careers. Instead, they hope that GenAI models and tools will improve so much that they could supersede the need for these foundational elements. This is especially hazardous wishful thinking for FSIs that haven’t yet scaled proven data-related technologies like ML. There is still time for a kitchen-sink approach while hoping for an Agentic AI miracle, but it won’t last.