Digital Metrics Don’t Just Miss the Mark—They Distract from Real FSI Performance

Also in this issue: The Persistent IT-Centric Trap of FSI Digital Transformation

Digital Metrics Don’t Just Miss the Mark—They Distract from Real FSI Performance

Just as decades of general industry experience don’t guarantee effective digital transformation leadership in FSIs, a pile of digital features doesn’t equate to financial performance. It’s what organizations do with their experience and digital capabilities that determines whether they end up with wasted effort or meaningful results.

One of the funniest examples is Bank of America’s quarterly presentations, which for years have highlighted growth in various digital metrics. It’s not just the CEO and business heads promoting the digital story—CFO Alastair Borthwick also joins in. In a recent earnings call, he noted: “…digital adoption and engagement continue to improve and customer experience scores rose to record levels, illustrating the appreciation of enhanced capabilities from these investments.”

Digital vendors and consultants are the biggest fans of FSI CFOs morphing into innovation cheerleaders. But did that “appreciation of enhanced capabilities” actually lead to customers spending more with BofA? Nope. Those record levels of digital metrics don’t seem to translate into groundbreaking financial performance. BofA’s overall and consumer banking revenue growth has barely kept up with inflation, and its efficiency ratio has remained stagnant.

The lack of impact can be traced back to how Bank of America leadership, including the CEO, thinks about digital capabilities. Brian Moynihan made headlines in 2021 when he declared that Bank of America is “clearly a technology company.” But his reasoning focused only on surface-level traits: a large portion of sales comes from digital channels, many client-facing processes are digital, and billions are being spent on technology annually. Nothing about financial performance. Nothing about operating model transformation.

So it’s no surprise that BofA can boast growing digital metrics while spending 12% of its revenue on technology, yet sees no acceleration in revenue growth or scalability. The leadership seems to be hoping for outcomes, rather than putting a strategy in place to drive them.

Unfortunately, this “hope is a strategy” mindset has taken hold across many FSIs. In conversations about business cases for digital investments, high-level assumptions abound, but actual evidence is rare. The same institutions that can model—with precision—the ROI of opening a physical branch often lack the same discipline when it comes to digital initiatives. Deep down, many suspect the returns won’t be there.

And FSIs don’t need to look to fintechs for inspiration here. Some of their peers have already rejected the worship of digital vanity metrics. Consider the contrast: BofA’s annual report is filled with dozens of references to digital capabilities and metrics. Capital One’s? Zero.

Firms like Capital One and Progressive treat digital capabilities as table stakes for maintaining customer experience—but more importantly, they’ve built and refined playbooks to scale innovation in ways that drive market share and financial outcomes. Otherwise, what’s the point of digital transformation?

This discipline is even more urgent for FSIs caught in the middle, wedged between large incumbents, fintech disruptors, and niche local players. Take U.S. regional banks: many have stock prices that haven’t budged since the late 1990s. Their traditional growth playbook relied on serial acquisitions. Now, forced to grow organically, they struggle to invest effectively in digital initiatives that drive high-ROI topline growth. The result? Stagnant revenues and efficiency, while digital metrics keep climbing, seemingly on autopilot.

To break out of revenue stagnation and expense ratio rot, FSIs must remember that only true digital transformation moves the needle. CEOs and CFOs can’t simply mandate high-ROI digital playbooks after sending teams through training.

The starting point for FSI leadership is always the same: identify where digital-driven revenue growth is most critical, assemble the best people into a cross-functional team with complete autonomy, and clear bureaucratic roadblocks until a visible P&L impact is achieved. Most importantly, stop including digital metrics in internal and external presentations. The ‘smoke and mirrors’ approach might buy you a few months, but it won’t work in the long run.

The Persistent IT-Centric Trap of FSI Digital Transformation

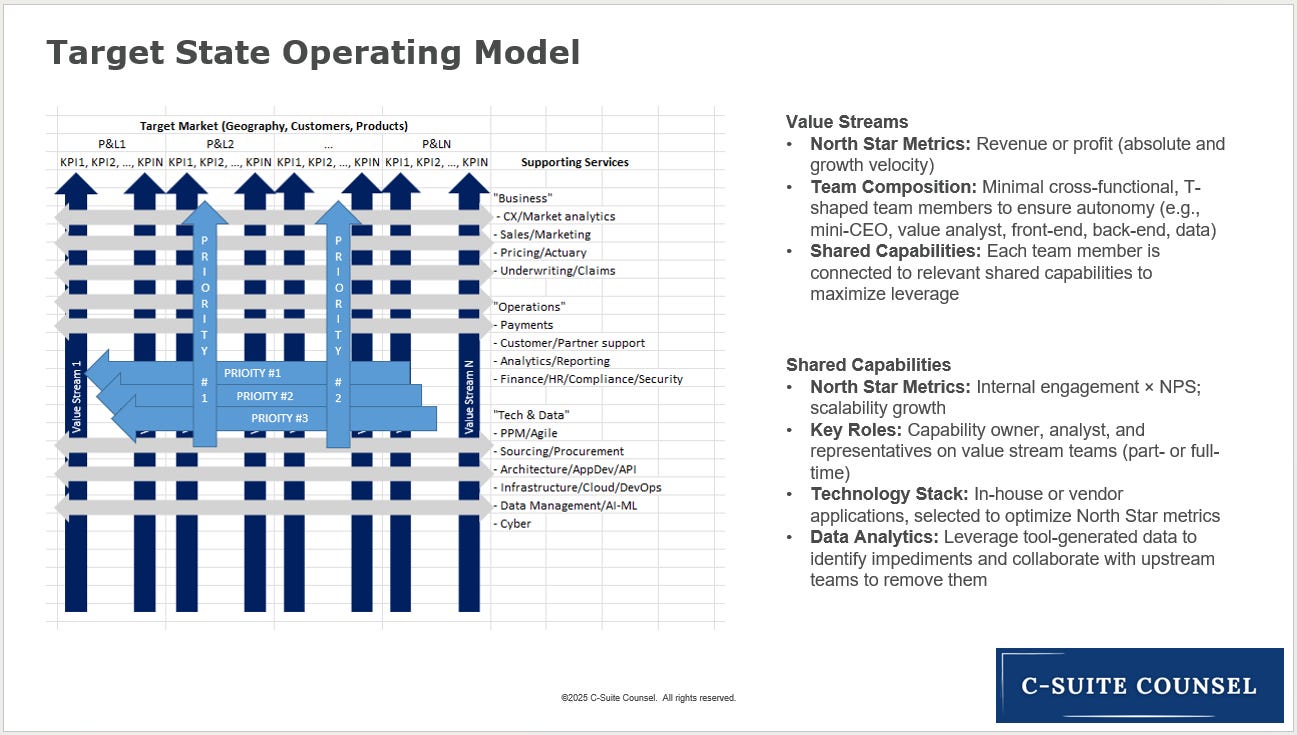

Our newsletter often illustrates a singular target state for the operating model at the end of the digital transformation journey: profit-generating value streams powered by a wide range of shared, enterprise-wide capabilities. As traditional FSIs evolve their operating models—from ad-hoc work to IT projects, then to IT products, and ultimately to value streams and platforms, they converge on this commonsense end-state. It may look chaotic from the outside, but within it, thousands of employees understand their exact responsibilities and cadences, both within and across the teams they collaborate with.

Of course, beneath each vertical and horizontal line in the above framework are dozens of sub-components. A large FSI might manage tens of core products, each with numerous revenue-generating features, all supported by hundreds—or even thousands—of microservices. Considering that many FSIs still struggle to coordinate customer targeting across channels and products, it’s no surprise we often say that no traditional FSI is likely to reach this target state in our lifetime.

That’s okay. Many traditional FSIs have business divisions that are still operating without undergoing a digital transformation. In any typical financial services or insurance company, there is a broad spectrum of digital maturity across business units and functions, even in the most advanced players, such as Capital One or Progressive. The key is to embrace this heterogeneity and transform one value stream and capability at a time, guided by business demand and the availability of talent and leadership focus.

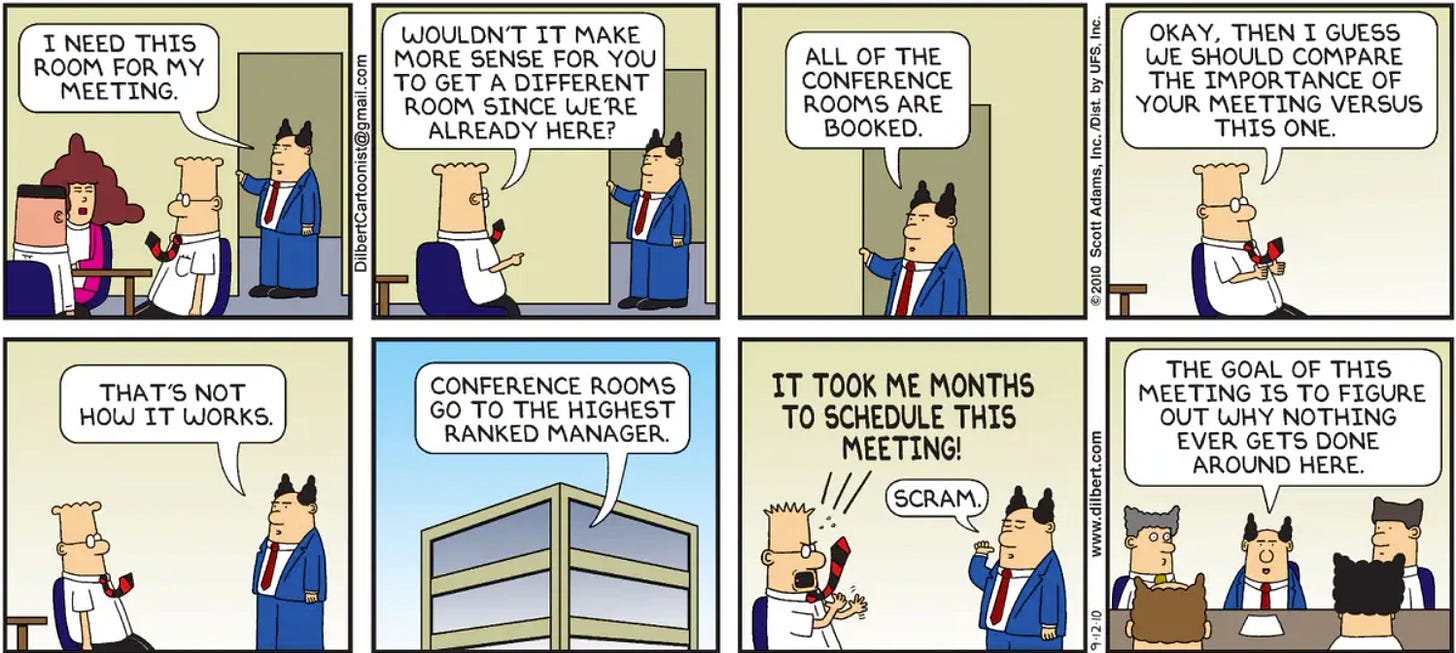

However, many FSIs find such a gradual approach too slow. When they reach the IT Product phase of digital maturity, the faster pace of launching new digital products often leads leadership to mistake it for enterprise-wide maturity. But it’s not—it's simply IT teams coding faster, while revenue-generating units and back-office functions are still operating at the pace of the IT Project phase.

This misinterpretation of speed as maturity often leads FSIs to overlook a proven 20th-century discipline: change management. When launching new digital solutions, their leadership tends to assume employees and end-users will act like mini-CEOs—proactively exploring every feature or turning to an always-available product team for support. In practice, post-rollout engagement is patchy at best, with many end-users unaware of how to access or use key features.

For example, telematics delivers meaningful value for commercial auto insurers only when their clients—fleet managers—act on the insights it generates by training, disciplining, or replacing drivers. This, in turn, requires the insurer to have a mature operating model that empowers employees to take ownership of change management, working closely with fleet managers. It's not an impossible task, but it does demand a steep learning curve across multiple internal stakeholders who are often used to working in silos.

I recently had a personal experience that highlights how even advanced FSIs like Chase struggle to launch digital products with a cross-functional operating model. After Chase began promoting the “spend instantly” feature for new card applications, I decided to try it out myself. The ROI seemed straightforward—by adding a couple of new APIs, there should be an apparent uptick in new card activations and usage conversions.

I paid the price for violating the cardinal rule of trying new features. Just like with new restaurants, it’s best to wait at least three months for the kinks to get worked out. My first attempt at using the new card via wallet was denied. Chase sent an authorization, which I confirmed, but the transaction was still rejected. I thought receiving a physical card a week later might help, but those transactions were also denied.

Realizing no digital resolution was coming, I called Chase’s Fraud Department—only to find that no one, not even the “senior specialist,” was aware of the new feature. He insisted Chase cards could only be activated after physical delivery. I explained that newly mailed cards no longer included an activation phone number or URL, but he didn’t believe me and kept repeating that I must have missed it. At least the card was eventually unblocked.

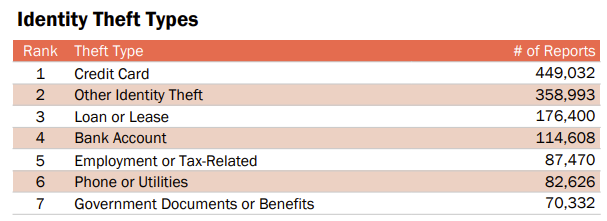

But did having a working physical card mean I could now log into the Chase website or use it in my digital wallet? Of course not. That required multiple separate calls. My curiosity to try a new digital feature was duly punished—by hours wasted navigating a banking experience trapped in a 1970s time capsule. To be fair, the Fraud Department did the right thing by stopping transactions and freezing the card. With identity theft being the highest among credit cards in the U.S. in 2024, and regulators holding banks increasingly accountable for all types of fraud, their cautious approach makes sense.

The problem lies in an overall siloed operating model that can’t keep up with the complexity of digital features launched across multiple products. Until digital product teams learn how to engage enabling functions and take ownership of driving change across those groups, these features will continue to be a net negative for both client experience and product P&L.

If your FSI is stuck in the IT Product phase of digital transformation, there's a simple mitigating technique: reallocate IT delivery capacity to the change management function. Until your operating model reaches fintech-grade agility, micromanaging change management is the only way to ensure ROI, or at least minimize frustrated end-users.