The Unbearable Lightness of Disruption in Financial Services and Insurance

Also in this issue - Learning from Leading Fintechs: Digital Transformation Insights for Global FSIs; The Law of Diminishing Returns in Digital Transformation in FSIs

The Unbearable Lightness of Disruption in Financial Services and Insurance

The thesis of FSI disruption is straightforward: a fintech would possess such maturity in its operating and technology capabilities that it could enable a superior business model. In practical terms, the solution would be 10X better in functionality, so it would rely on inexpensive word of mouth, allowing for 10X cheaper pricing with full digitization and no marketing. The resulting unit economics would be virtually impossible to replicate, pushing traditional FSIs out of business. Getting there might take a decade with billions spent upfront until scale is reached, but that’s what VCs are for.

Since Amazon, Spotify, and Netflix achieved this, obliterating old timers, the general view remains that for financial services, it’s not a question of IF but WHEN. Is it though? One of the best illustrations of such expectations vs. reality is Wise, launched in 2011. Its playbooks are out of reach for a typical FSI, and it has become the largest cross-border money transfer firm, surpassing Western Union’s volumes in 2023. From inception, Wise has promised as its #1 mission to push prices close to zero, making it impossible for banks and MTOs to compete. And yet, Wise’s average price (aka, “take rate”) has remained the same for a decade, even increasing at times:

To explain the lack of progress in lowering pricing while growing 100X, Wise would regularly offer excuses, blaming everything from underestimating the AWS bill to unexpected product losses. As a result, the stock is 40% off the highs, and growth is slowing down. Without lower pricing, the main competitors could match Wise’s offering where customers shop around, or even beat it in some money transfer corridors, like the US to India:

Wise will continue to gradually gain market share, but why can't it lower prices by 10X to push competitors out of business? A new fintech Atlantic Money offers a potential answer. Its price is 10X lower than Wise, which resulted in unprecedented growth, running a year ahead of Wise. On track to transfer $0.5 billion this year, how much revenue would Atlantic Money generate in 2024? Since the new fintech charges so little, its revenue would be around half a million. And if it grows 10X in the next few years, the revenue would still be only $5 million.

The hope is that as Atlantic Money conquers the world its minuscule fee across 100 million customers will eventually cover fixed costs. However, that is a big assumption. How likely is it that they will have less fat in the operating model at scale or better technology compared to such a superb operator as Wise?

A similar breakdown of challenges behind trying to disrupt incumbents came from the recent WSJ article about Bilt Rewards. Last month, I profiled this innovative but incredulous partnership among Bilt Rewards, Wells Fargo, and Mastercard. As probably the most interesting credit card products of the 21st century, have they finally figured out a business model to capture half a trillion in rental payments without charging a fee?

The app's UX is beautiful, and Bilt’s loyalty platform is second to none. For 50 million renters in the US, this could be an attractive value proposition. However, with rent coverage being a loss leader for the partnership, renters would have to use the Bilt card for all purchases, ditching incumbents like Amex, Chase, and Capital One.

That hasn’t happened yet. The WSJ recently reported insider information indicating that Wells Fargo could be losing $10 million per month on this partnership, purportedly due to overly optimistic initial assumptions: 1) expecting 65% of card purchase volume to be non-rental, when in reality it's the opposite; 2) anticipating 50-75% of customers to carry balances, whereas the actual figure is 15-25%.

It took years for Amazon, Netflix, and Spotify to fine-tune their business models, so there is still hope that fintechs like Atlantic Money and Bilt will finally drive a real disruption of FSIs. However, the current leaders won’t stand still. They will copy the business, operating, and technology models of these disruptors if they perceive a real threat. What can’t be copied, aka “the secret sauce”, is unknown for now. In the meantime, we can enjoy the incredible deals from these players, courtesy of VCs and others who fund them.

Learning from Leading Fintechs: Digital Transformation Insights for Global FSIs

"Every cross-functional effort on a global scale has failed. Departments and regions don’t want to share their best employees for free, we don’t have an internal finance process to compensate them, and I don’t get a budget to hire the same resources for my team," explained a global head of the client segment for a $50+B revenue FSI. The role was created to accelerate revenue growth in the promising segment, but with no change in the global operating model, it was designed to fail.

Digital transformation of one business line in one country is challenging on its own; should FSIs even consider a global digital transformation strategy? Some clearly do, as evidenced by Santander's recent announcement. In an unprecedented move, Santander has embarked on developing a global core platform internally, initially focusing outside its domestic market with plans to encompass both Retail and Commercial businesses. In a recent interview with Reuters, Santander’s Executive Chairman, Ana Botin, shared the rollout vision:

"Our goal is to build a common platform for our retail and commercial business, using our own technology. It is coming together in the U.S. this year, but we'll be slowly, but steadily rolling it out across our footprint.”

As a prerequisite, an FSI must achieve Level 4 digital maturity (Value Stream & Platform - refer to the picture below) within the business unit and country where it intends to develop a core platform. None of the global FSIs have attained this level of maturity across all business lines and countries, hence a phased implementation is crucial.

Santander, at least, won't be starting from scratch; it has already established effective front-end capabilities in a couple of countries. However, the question remains whether the bank will have the patience to limit expansion to divisions and countries that are already sufficiently mature. Typical behavior among large global FSIs is to expedite efforts for short-term gains, influenced by the expectations of Wall Street analysts, often preying on improved technology to address shortcomings in operating at Level 3.

Even among the best neobanks, Santander’s vision is unheard of. For example, Starling Bank has achieved impressive differentiation after a decade: its non-staff running costs are down to 1% of revenues due to building an increasing portion of its capabilities in-house. However, the neobank still focuses on one business line in one country.

Global roll-outs of in-house platforms are more commonly seen among specialized fintechs that do not yet provide a full range of banking services. For example, Brex is pursuing a global play for its in-house-built expense management product. In a recent interview with Tech Crunch, Brex’s CEO, Pedro Franceschi, explained the differentiation thesis:

Franceschi claims that Brex’s advantage is that it built its tech stack “vertically integrated down to the Mastercard rails and the ACH rails and the money movement rails,” whereas some competitors built their business on top of other platforms such as Stripe or Marqeta.

That works for more simple use cases, he said. But for more complex scenarios such as global coverage, depth of integration helps.

The idea makes intuitive sense - without in-house core systems, what differentiates your fintech or even traditional FSI in the long run? But the ROI is far from obvious, especially with proven integrated and modular platforms available on the market. For Santander or even Brex, the practical question is whether they could build a better solution than dedicated vendors like FIS, Marqeta, or Stripe. Otherwise, if their solution is comparable or, more likely, worse, the downside of having to rely on a partner to localize it for every market would be irrelevant. Some global fintechs also rely on partners for core capabilities to quickly deploy in new countries, but with Santander’s existing footprint, speed may not be as critical.

The ultimate value of an internal platform could be to monetize it with competitors, similar to Blackrock’s Aladdin, which generates $1.5B in revenues. However, the market demand for such operator-built systems is very different now than a quarter century ago when Aladdin was first introduced. As a final lesson to aspiring global FSIs like Santander, Wise has been attempting to monetize its platform for almost a decade and has signed 85 clients. However, when its leadership was recently asked if its Platform business generates any significant revenue, the answer was “still early days.”

The Law of Diminishing Returns in Digital Transformation in FSIs

Since digital transformation has become a buzzword that sounds impressive to analysts and employees, it is often used as a substitute for meaningful progress in IT. That is acceptable for FSIs that lack the ambition to accelerate growth. MetLife provides a perfect illustration: by distancing IT employees from its business counterparts and outsourcing the majority of development and maintenance capacity, the company has mostly aimed to achieve efficiency. A recent article in BuiltIn elaborates on what “digital transformation” entails in such an environment:

This nicely aligns with MetLife’s go-to-market strategy. The company already holds a leading market share in corporate life/benefits insurance, focusing on clients such as heads of HR who prioritize learning and diversity. With no foreseeable disruption on the horizon, there seems little incentive to pursue actual transformation.

We often discuss how transformation could prove counterproductive for business lines where customers highly value in-person advice, such as in money management. For them, the traditional branch footprint remains essential, as it serves as the venue for advisory appointments, which have tripled for Citi in the last 2 years and increased by 50% for Bank of America since 2017.

A leaked EY presentation to Barron’s regarding Citi's Wealth division illustrates the dynamics in such lower digital density environments. Front-end initiatives without corresponding back-end redesign do not yield significant impacts, and there is minimal demand from front-line champions for back-end modernization:

One of the slides in the bank’s audit showed recently funded “surface-level” initiatives, listed around the top of an illustration of an iceberg. Initiatives labeled as “historically underfunded” were named beneath the larger part of the iceberg, floating under the surface.

Recently funded initiatives viewed as “surface-level” included a unified wealth workstation and client reporting. Underfunded initiatives included its alternative investments platform, record-keeping, a single platform for the core compliance element known as know-your-customer, and a margin-lending offering.

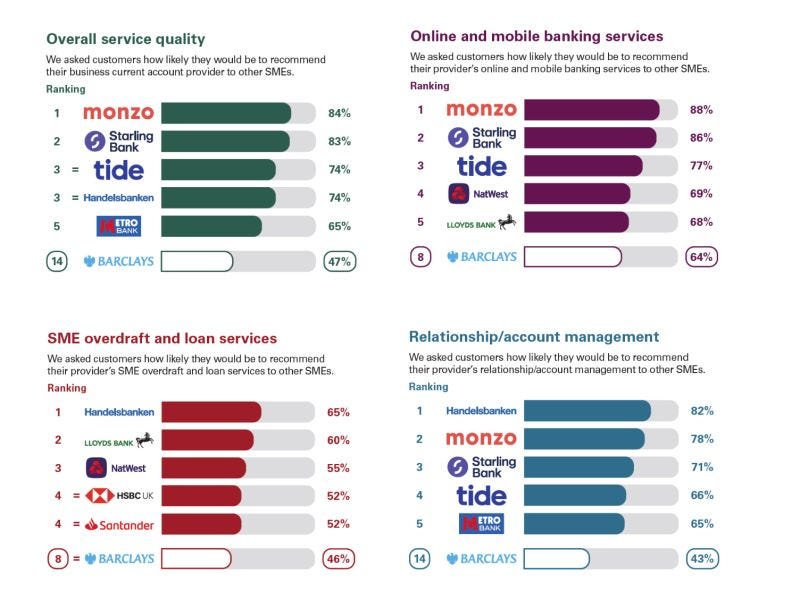

In the UK, top banks are obligated to participate in and publicly disclose the results of industry-wide client surveys (both consumer and business) on their websites. For instance, Barclays must acknowledge that it holds the second-worst service quality rating for business accounts among the top 15 players, significantly trailing leading fintechs. Such lower customer engagement could mean a potential rapid loss in market share unless Barclays embarks on a digital transformation journey, right?

Not necessarily. A relatively low NPS might not be as critical as absolute numbers, which, in Barclays' case, appear to be sufficient. Business Banking has actually been their fastest-growing division in the UK.

Furthermore, justifying digital transformation becomes even more challenging when customers already express high satisfaction with your FSI's digital capabilities, as seen in a recent survey of Canadian banking customers. Previous digital initiatives have already yielded satisfaction rates of 95-97% for ATMs, mobile apps, and online banking.

Finally, let’s remember that significant targeted improvements occur frequently without undergoing full-scale digital transformation. Morgan Stanley's CEO recently referred to one such initiative as an "enormous productivity quantum," aiming to save financial advisors 10-15 hours per week. One advisor described this change to me as "amazingly efficient." What brought about this magic? A GenAI-based tool that eliminates the tediousness and errors of note-taking following client discussions.

The law of diminishing returns suggests that large-scale digital transformation would increasingly yield mixed ROI, making niche improvements the primary focus. Lower stress, reduced expenditure, and comparable outcomes seem like an all-around win.