The Flywheel vs. Real Scaling in Digital Transformation for FSIs

Also in this issue: GenAI Can Drive Efficiency in FSIs, but Differentiation Lies in Top-Line Use Cases

The Flywheel vs. Real Scaling in Digital Transformation for FSIs

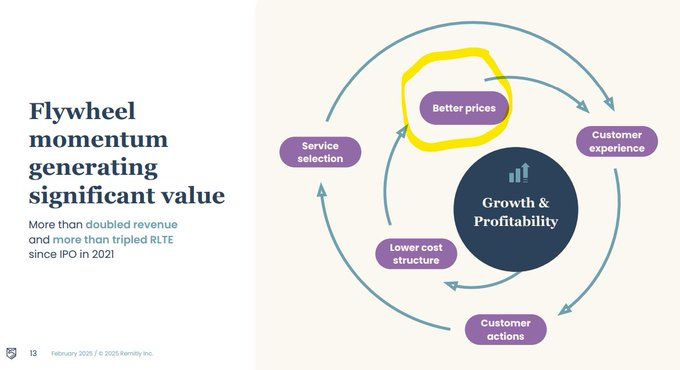

When King Solomon taught the Israelites that “there is nothing new under the sun,” the fintech world’s favorite concept—the “flywheel”—may have already existed. It’s common sense: a more efficient gold trader in ancient times would generate higher profits, allowing for lower prices. Eventually, prices could drop so much—while maintaining top-notch service—that competitors would be forced out. Three millennia later, Remitly highlighted this very idea in a recent investor presentation:

Price-driven competition in financial services and insurance is also not a 21st-century phenomenon. Vanguard reshaped asset management five decades ago, while Progressive did the same for auto insurance three decades ago by competing on price. Today, they dominate as industry incumbents, while startup challengers struggle to gain significant market share. So far, no one has found a significantly leaner way to generate a flywheel in these markets.

To celebrate its 50th anniversary, wealthtech OG Vanguard announced “the largest fee cut in history.” Yet, for a $10 trillion asset manager, this move saved consumers just $350 million—highlighting how lean the space already was. This also helps explain why upstarts like Betterment remain a hundred times smaller even after 15+ years.

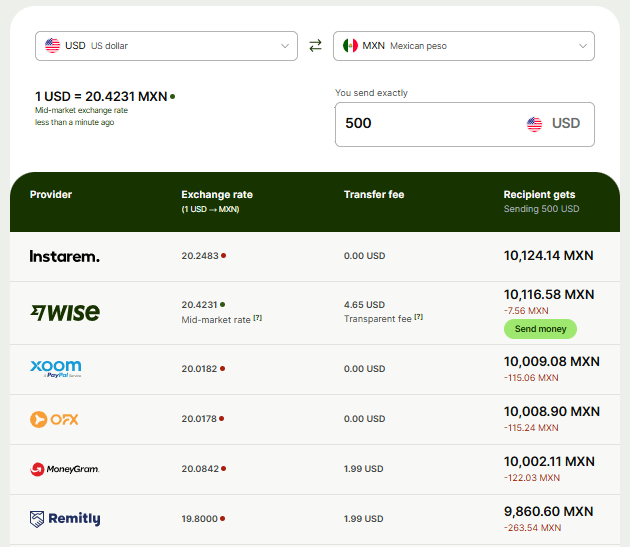

The irony of Remitly’s flywheel diagram is that the company only started emphasizing it last year—more than a decade after its launch. Even more telling, Wise has preached its mission to drive transfer costs to zero from day one, yet it only began meaningfully lowering its average markup last year. Both firms have realized that there's little urgency to cut prices if consumers are already flocking to them. In the world’s largest remittance corridor, the U.S. to Mexico, Wise is only slightly cheaper than incumbents, while Remitly remains among the most expensive—not exactly a "10X" advantage.

Another supposed "10X" flywheel component was customer service. The theory was that traditional FSIs prioritize profits, while disruptors sacrifice margins to keep customers happy. In reality, the opposite often played out—some fintechs leaned too heavily on self-service, leaving customers frustrated and wanting traditional human support. In a recent surprise, the UK government’s banking customer satisfaction survey ranked Chase ahead of neobanks after just three years in the market.

Instead of a mythological “flywheel,” what always works is strict adherence to the first rule of capitalism: give people what they want. Consumers and businesses have unmet needs or desires for which they’re willing to pay. For example, lower-income consumers often seek ways to buy what they can’t immediately afford. U.S. regulators and politicians pushed banks out of serving them, leaving payday lenders as the only option—until BNPL firms like Sezzle emerged. However, because these companies were labeled “fintechs,” few seemed to mind them targeting habitual borrowers.

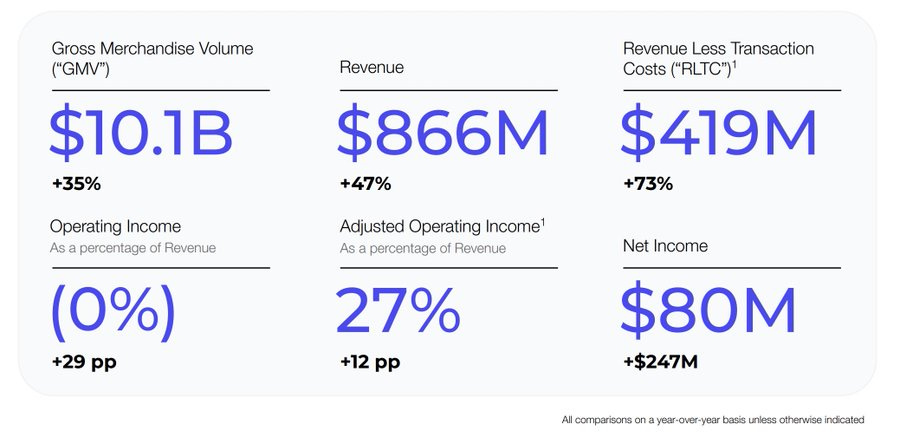

No BNPL player or credit bureau is incentivized to disclose what percentage of customers end up in worse financial shape. FICO even partnered with Affirm to produce a rosy report filled with generalities. Like Sezzle, Affirm has been on a tear—recently matching SoFi’s Lending division in net revenue while growing four times faster.

Before Affirm and other BNPL players launched their products just over a decade ago, I often wondered why such a popular product in developing countries hadn’t gained traction in the U.S. There were attempts like Bill Me Later, but none had the intensity needed to break through merchants' acceptance barriers and consumer hesitance. As Affirm and others launched, PayPal didn’t see it as a call to overhaul risk models or acquisition processes for Bill Me Later. Instead, leadership spent a decade acquiring companies worldwide—many of which weren’t even integrated.

Similarly, Remitly’s revenue is over 50% higher than Western Union’s digital division, despite launching much later—not because of some unique flywheel component like pricing or customer experience, but due to a more advanced operating model. Like Progressive Insurance, Remitly’s success lies in precise targeting. While well-performing consumer fintechs have a customer lifetime value (LTV) to cost of acquiring them (CAC) ratio of 3:1, and top performers reach 5:1, Remitly claims a 6:1 ratio.

The tricky part—and where many large FSIs and well-funded fintechs get burned—is profitably addressing pain points or wants. The most intriguing credit card in history, Bilt Rewards, won over U.S. renters by satisfying their craving for points at no cost. However, as the WSJ first reported in 2024, Bilt seems to be struggling with economics. In a recent letter to customers, its founder hinted at raising the overall spending requirements for earning points on rentals (currently, it’s just four additional transactions of any kind).

“Ensuring long-term value for everyone. Waiving the standard 3% card fee on rent payments represents a significant cost to the program—and unique value that we provide to Bilt cardholders. Ensuring this benefit goes to members who genuinely engage with our broader program—rather than those taking advantage of loopholes—will allow us to continue delivering long-term value for our entire cardholder community.”

Rather than constantly changing terms, leading traditional FSIs and fintechs that compete on price ensure positive unit economics across all client segments and products from the start. For this reason, Wise could be among the more expensive providers in corridors where competitors are willing to lose money to maintain market share. Similarly, Mercury offers no yield on deposits below $500K for its small business customers and applies an increasing yield for much larger amounts.

When your CEO or Board asks for a “flywheel” in your traditional FSI, tell them that real scaling of digital use cases is much simpler. You just need their approval for an autonomous, cross-functional team of top talent with unbridled intensity. The best way they can help you afterward is to push you to go faster periodically.

GenAI Can Drive Efficiency in FSIs, but Differentiation Lies in Top-Line Use Cases

Significant cost cuts in financial services and insurance companies are straightforward. Ask revenue-generating business heads which enablement from enterprise functions they’re willing to pay for, and cut the rest unless regulators require it. Of course, that rarely happens because enterprise groups would have to scramble to sell business heads on adding clear value—a task they typically lack the skills and interest to pursue.

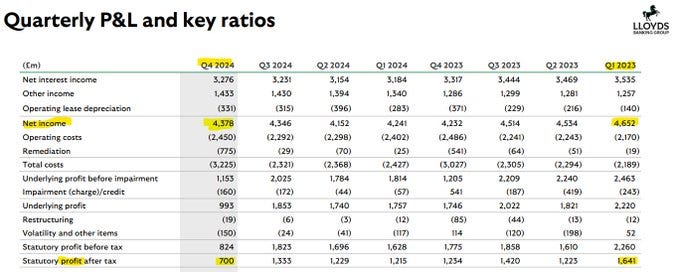

Instead, FSIs' enterprise groups and business lines pursue various concurrent technology investments and cost-cutting efforts, hoping for the best. In its recent investor presentation, Lloyds announced 30% reductions in data centers, a 20% gross reduction in run and change technology costs, and other cost-saving achievements. Yet, over two years, revenue has been down 6%, and more surprisingly, despite all those cost-cutting efforts, profit has been down 57%.

In such a complicated context, it becomes more understandable why, after two years of substantial investment, dedicated governance, and relentless GenAI promotion on every investor call, even leading FSIs have struggled to identify specific near-term productivity targets. If proven technology no longer generates expense ratio cuts, novel solutions are even less likely. In a recent interview with the WSJ, Teresa Heitsenrether, JPMorgan’s Chief Data and Analytics Officer overseeing the firm’s AI strategy, answered “too early” to all questions about returns on GenAI.

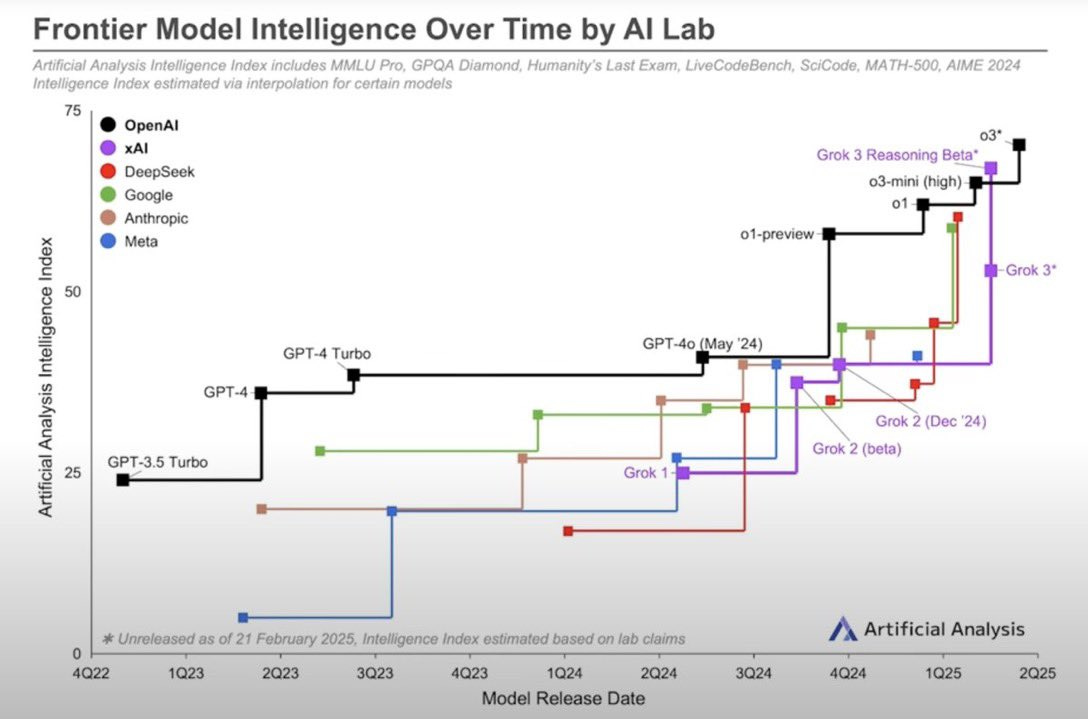

More interestingly, Teresa’s responses suggested that meaningful productivity gains may never materialize for JPMC unless GenAI models significantly improve reasoning. The good news, however, is that while progress seemed to stall a year ago, more recent versions have markedly improved.

Like Bitcoin, where each halving requires more energy, creating more advanced GenAI has become a compute energy arms race. What remains unclear is what will specifically create a significant competitive advantage for leading FSIs. It's certainly not the underlying GenAI model—no FSI wants to join this compute race. Instead, leading players have focused on uploading their proprietary datasets into top vendor models and experimenting with various use cases. As with JPMC, the common hope is that AI agents will eventually develop enough reasoning ability to replace employees at scale.

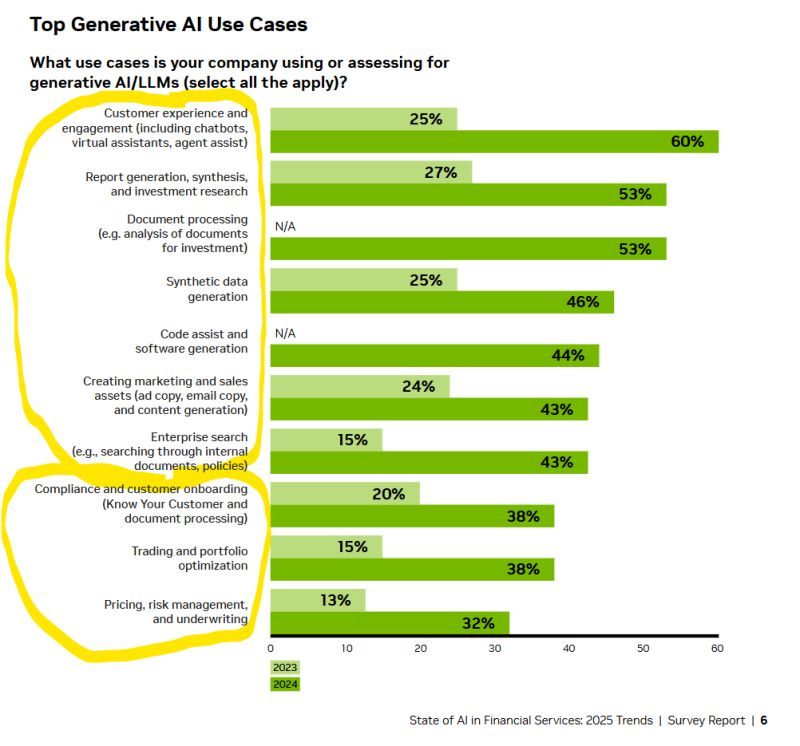

A decade ago, scaling machine learning primarily targeted processes with the most repetitive tasks: customer service, underwriting, and fraud prevention. The main addition to generative AI is its potential to make developers more productive. HSBC CEO Georges Elhedery recently described these common focus areas, highlighting how the scope of automation has expanded from operational efficiencies to improving the productivity of highly skilled roles like software development.

“Our flagship initiatives will focus on improving customer service through both our mobile apps and our contact centres. We also intend to increase tech productivity with tools such as coding assistants, and improve process efficiency in areas such as onboarding, KYC, credit applications and many others.”

It makes sense for FSIs to start with easier GenAI use cases, which could still deliver minimal ROI if paired with disciplined layoffs or hiring freezes (if revenues are rapidly growing, like Klarna). For example, Rick Weller, CFO of Euronet Worldwide, recently described how they limited the opening of new customer service centers by enabling non-native speakers to toggle across languages using AI:

“We work off of a single platform. Each time we go into a market, we're not having to redevelop the process. We leverage our technology across these businesses. Even for example, we don't have to set up different customer service centers because we use AI applications to toggle between languages.”

For leading FSIs with ambitions to differentiate through GenAI, the focus can't be solely on efficiency and productivity. Without much faster revenue growth, traditional technology paired with cost-cutting playbooks would be sufficient in most cases. These FSIs need to place one or two strategic bets to accelerate market share growth, focusing on much harder use cases with their best limited talent.

Just be careful with edgy names for your GenAI-based product teams. What might have been creative in the 1970s could be perceived as inappropriate when applied to a foundational vendor model that adheres to politically correct safeguards.