Why Do FSI CEOs Keep Ignoring the Point of Digitalization Efforts?

Also in this issue: Many Traditional FSIs Are Still Too Proud to Learn from Leading Fintechs

Why Do FSI CEOs Keep Ignoring the Point of Digitalization Efforts?

A typical FSI today has the same market value as it did a decade ago, with revenue growth lagging behind inflation. Yet, quarter after quarter, their CEOs describe financial performance as “positive,” “encouraging,” or even “strong.” This narrative seems effective—financial services CEOs enjoy the longest average tenure across industries, at over 8 years. For larger players, that number rises to 11 years. So, what’s their strategy?

Historically, acquisitions have been a favored method for FSI CEOs to demonstrate strategic growth to investors. While some succeed spectacularly—like JPMorgan Chase, which has absorbed over 1,200 institutions over 225 years—most acquisitions struggle. Integrating even smaller peers proves more difficult than anticipated.

Now, Truist, a top-10 U.S. bank, is learning that operational and IT redundancies on paper often conceal deeper differences in operating and technology models, as highlighted in a recent American Banker article:

Back in 2019, BB&T and SunTrust executives also projected that Truist would reach a 51% efficiency ratio, achieved partly through cost savings of $1.6 billion, by 2022. The company’s adjusted efficiency ratio for 2023 was 58.8%, and its unadjusted efficiency ratio was even higher.

Fortunately, for over a decade, FSI CEOs have found a new way to demonstrate long-term strategic vision. Instead of relegating technology to a cost center, digitalization has become a key focus of investor presentations, with spending soaring. While investor scrutiny on tech expenses is increasing, the industry hasn’t cut back—especially larger players, who are spending 10% or more of their revenues on technology.

JPMorgan Chase, the bellwether for the sector, recently reaffirmed its commitment to ongoing tech investments and faced virtually no pushback from investors. Its stock remains near all-time highs, with a market capitalization of $0.6 trillion, maintaining its position as the world’s largest bank. Its COO, Daniel Pinto, recently explained in a CNBC report:

When it comes to expenses, the analyst estimate for next year of roughly $94 billion “is also a bit too optimistic” because of lingering inflation and new investments the firm is making, Pinto said.

“There are a bunch of components that tell us that probably the number on expenses will be a bit higher than what is expected at the moment,” Pinto said.

But what is the point of FSIs spending so much on digitalization-related efforts with technology spending around $1 trillion globally? It should be to accelerate top-line or scalability growth, or ideally both. If the resulting revenue is growing and the expense ratio is declining much faster than the baseline, then the CEO has likely mastered digitalization and could keep their job.

That approach has so far been relevant to fintechs and some leading traditional FSIs, but it’s not the norm even among large players. Typically, the CEO and C-suite don’t push for those North Stars, leading to alternative ways of proving differentiation to investors. For example, in a recent presentation by U.S. Bank, a top-5 bank in the U.S., five years of digitalization efforts were measured by industry awards and vanity metrics:

Unfortunately for such FSIs, digital features don’t guarantee a "wow" factor that drives viral growth. Ally Financial, which promotes itself as a digital-only bank redefining innovation and leading the industry in GenAI, has seen its stock price barely increase in a decade. Despite all its digital features, customer reviews on Google Play and Trustpilot suggest they aren’t experiencing the promised tangible benefits:

Some FSIs provide more tangible proof of their digitalization efforts. In a recent CNBC interview, Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan highlighted the "fantastic" outcomes after 14 years: a 25% reduction in headcount while doing more digital “stuff.”

“… in 2010, I became CEO. The management team took over and they have done a fantastic job. We had 285,000 people. We went up to 305,000 people. Today, we have 212,000 people. The company is bigger. We do more stuff. We have a lot more customers doing a lot more transactions, whether it’s in markets or banking or consumers or wealth management customers, and yet we have been able to — that’s all through the power of digitization.”

Cutting manual labor through digital capabilities is a key component of digital transformation, and Bank of America’s stock price has almost tripled since Brian Moynihan took over. Yet, revenue growth has lagged behind inflation over that period. Ironically, Brian likes to compare Bank of America to a technology company. Can you imagine the CEO of a digital native or fintech failing to keep up with inflation for over a decade? You can’t, because they wouldn’t last that long.

The reason is that higher scalability isn’t the ultimate goal of digital transformation. The purpose of digitalization efforts is to accelerate revenue growth by destroying competition and launching new business models. For now, traditional FSI CEOs will continue to ignore this point since the Board and investors are content with the status quo. But this won't last.

Many Traditional FSIs Are Still Too Proud to Learn from Leading Fintechs

Fintech disruption of the second wave after 2010 can be broadly divided into three phases:

2010-2020: Too small to matter

2020-2030: Large enough for incumbents to stop growing

2030-2040: Pushing incumbents out of business

This progression varies widely across client segments, product lines, and regions. Simpler consumer financial products have been impacted more quickly. For instance, Western Union’s cross-border revenue has been stagnant for a decade. Meanwhile, auto insurance incumbents would barely notice if all insurtechs disappeared tomorrow.

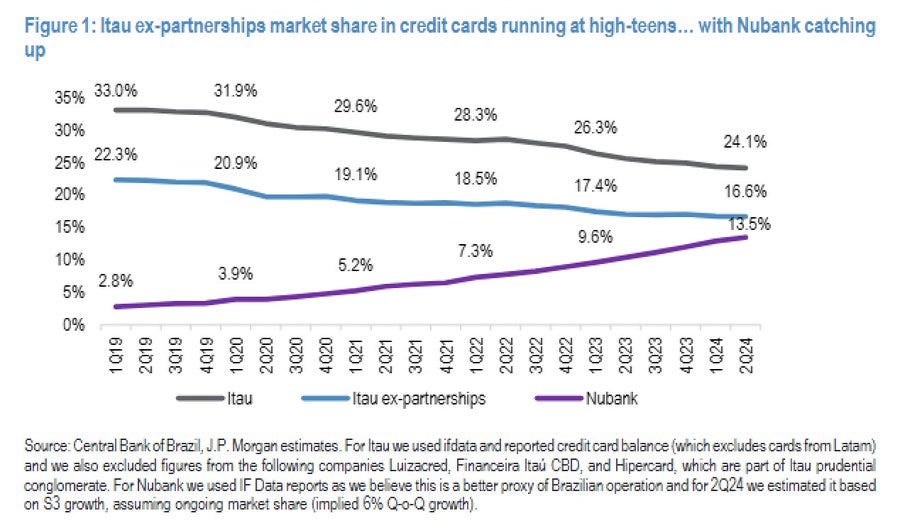

Even when an incumbent is losing market share, it can be masked by overall revenue growth as the market expands. Nubank, one of the most impressive consumer finance stories outside of China, is rapidly catching up to Itaú’s credit card market share in revenue. However, it will be years before the incumbent is in any real danger of losing that particular business:

The inevitability of disruption in some financial services markets stems from the significantly faster growth rates of leading fintechs. Starting from a small baseline, the compounding effects over decades become overwhelming. This rapid growth is driven by a focus on real market pain points and the development of sustainable business models enabled by advanced operating and technology capabilities.

For an example of such capabilities, Klarna recently made headlines by announcing it would switch from using enterprise SaaS vendors like Salesforce and Workday to niche vendors for external tasks, such as payroll tax and compliance. Instead, Klarna will build the remaining software in-house. Their operating model and talent are strong enough to develop high-quality internal software, and they know how to leverage their data (about clients, employees, etc.) rather than relying on proprietary vendors:

But what should executives at incumbents like Itaú do to avoid a similar fate of disruption by digital natives? Fortunately, an FSI CEO does not need a sage to tutor them like Aristotle did with Alexander the Great. Many of the world’s most effective fintechs are transparent about their operating and technology models and share their lessons learned.

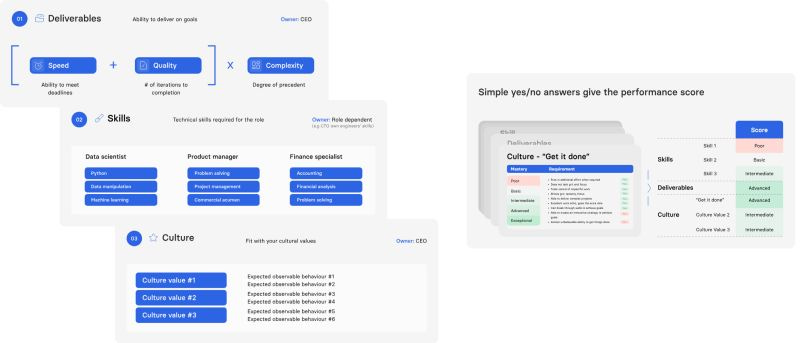

For example, Revolut’s founder recently published an employee performance management playbook. Similar to Wise’s publications on their KPI trees, this playbook might seem too intricate and unattainable for most traditional FSIs. Nevertheless, understanding these target states through real-world examples can help guide incremental improvements in operating and technology models.

Unfortunately, in my experience, only a small percentage of FSI executives are eager to learn from players like Revolut on how to operate more effectively. Many still view fintechs with billions in revenue as irrelevant to their complexity. Instead, they continue to stumble through various organizational designs and reassignments of responsibilities, hoping something will work. Even these changes are often driven not by internal introspection but by external pressures, such as criticism from analysts or regulators.

In July, Citi was fined $136 million for insufficient progress in addressing data management issues identified in 2020 and was required to intensify its efforts. This seems to have prompted Citi’s recent attempt to address its data problems with new personnel and roles:

In this latest iteration (the third in three years), responsibility for fixing master data management has shifted from the COO + Chief Data Officer to the CTO + Head of Enterprise Data:

Tim Ryan, the former accountant and top PwC partner who joined Citi in June as Chief Technology Officer, will lead the data overhaul. Ashutosh Nawani, Head of Enterprise Risk Management, will join Ryan's team in the newly created role of Head of Enterprise Data Office and Data Transformation.

COO Anand Selva will continue to oversee the bank’s broader efforts to improve risk controls and back-office operations. Chief Data Officer Japan Mehta will assume a new role.

Hopefully, the data issues will be resolved this time, and internal politics will take a back seat to business sense or, at the very least, regulatory pressure. More broadly, C-suite executives in traditional FSIs should recognize that they are missing out on valuable resources for enhancing their operational capabilities. The practical insights into how leading fintechs build their capabilities, along with lessons learned, are available for free: