What Does It Take for FSIs and Fintech Vendors to Differentiate Their Digital Capabilities?

Also in this issue: Some FSIs Conflate Organizational Design with Operating Model to Avoid Accountability

What Does It Take for FSIs and Fintech Vendors to Differentiate Their Digital Capabilities?

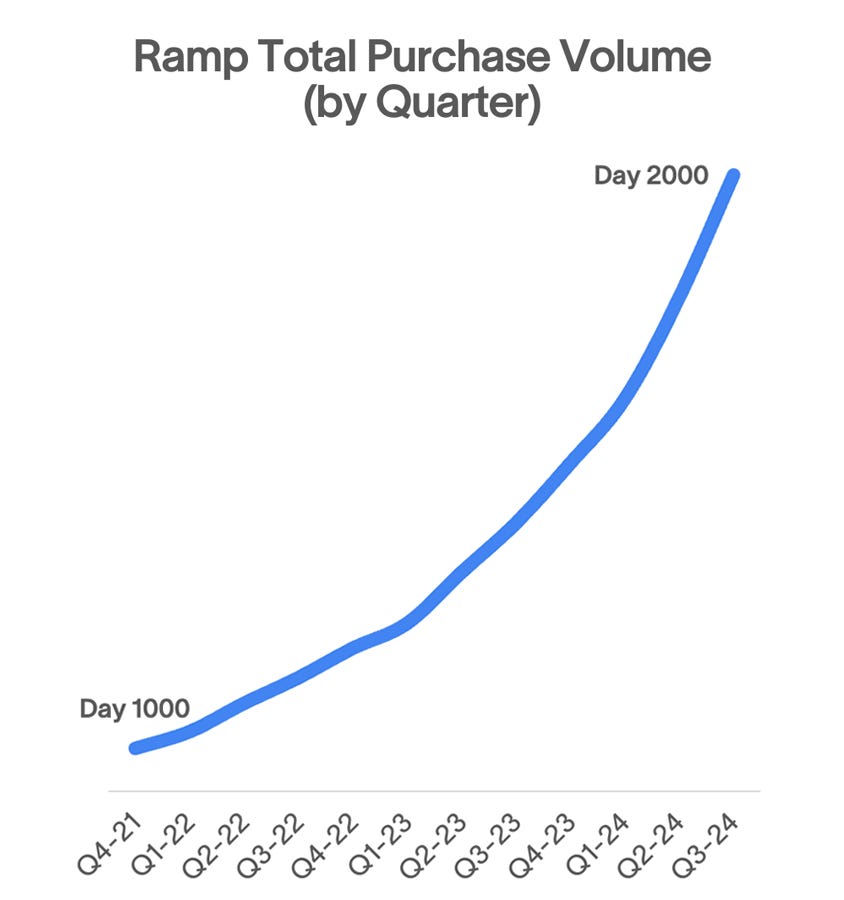

Scaling digital use cases is straightforward for financial services and insurance companies when they have clear differentiation for their target segment. For instance, Ramp, one of the fastest-growing fintechs in history, focuses on companies with substantial finance operations, offering them approximately 5% savings in time and money:

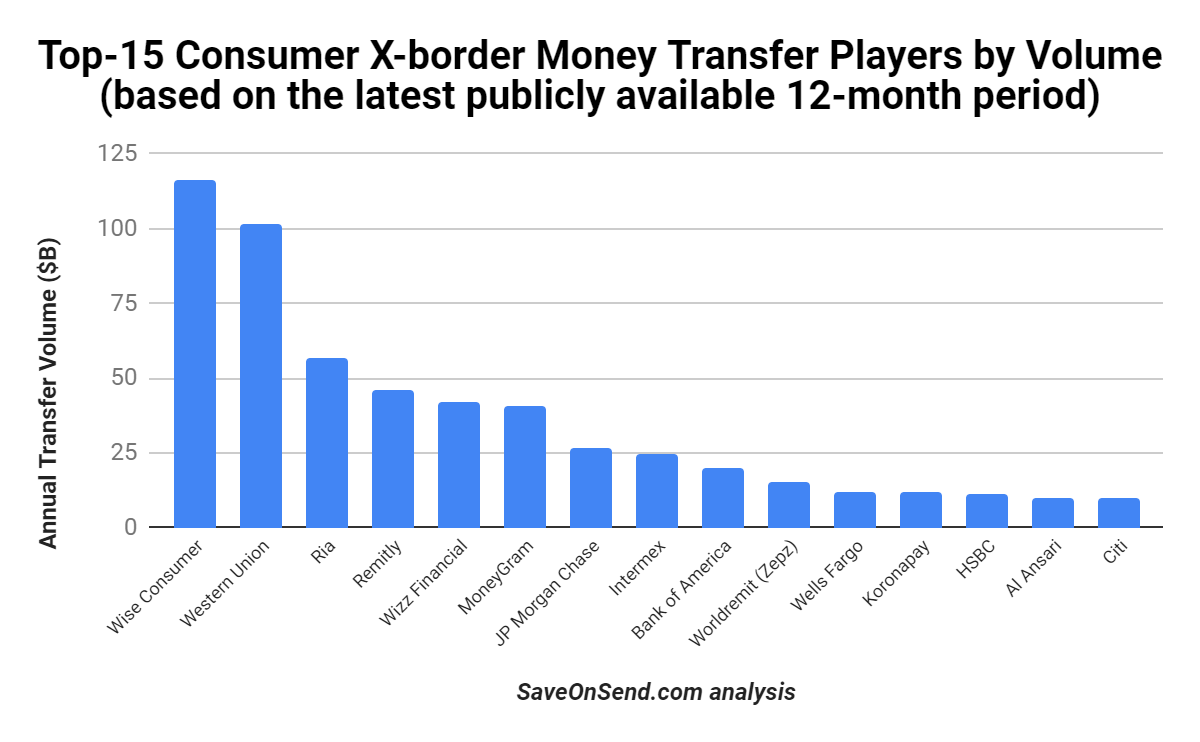

Theoretically, such differentiation could be sustained indefinitely by new-generation companies that discover novel business models or more scalable ways to deliver solutions. For example, in cross-border consumer money transfers, the last four decades have seen new companies emerge every decade or so, each offering a better value proposition:

Chase → Western Union → Xoom → Wise → Atlantic Money

Fifteen years ago, conventional wisdom held that a new entrant needed to be 10X better across all dimensions—pricing, UX, speed—to displace an incumbent. However, this has become nearly impossible as incumbents continue to evolve. For instance, in its early days, Wise (then TransferWise) claimed that incumbent banks and Western Union charged up to 10X more, allowing customers to save up to 90%:

That was never the case. After being repeatedly reprimanded by the UK government for such "growth hacking," Wise explained that it hadn’t checked the actual prices. The promised advantage was gradually reduced—first to 5X, then to 3X—before eventually being removed from its website and marketing materials. Yet, like Ramp's rapid growth, Wise's lack of a 10X advantage didn't hinder its expansion. By 2022, just a decade after its launch, Wise became the world’s largest C2C cross-border transfer player by volume, and its lead has only continued to grow since:

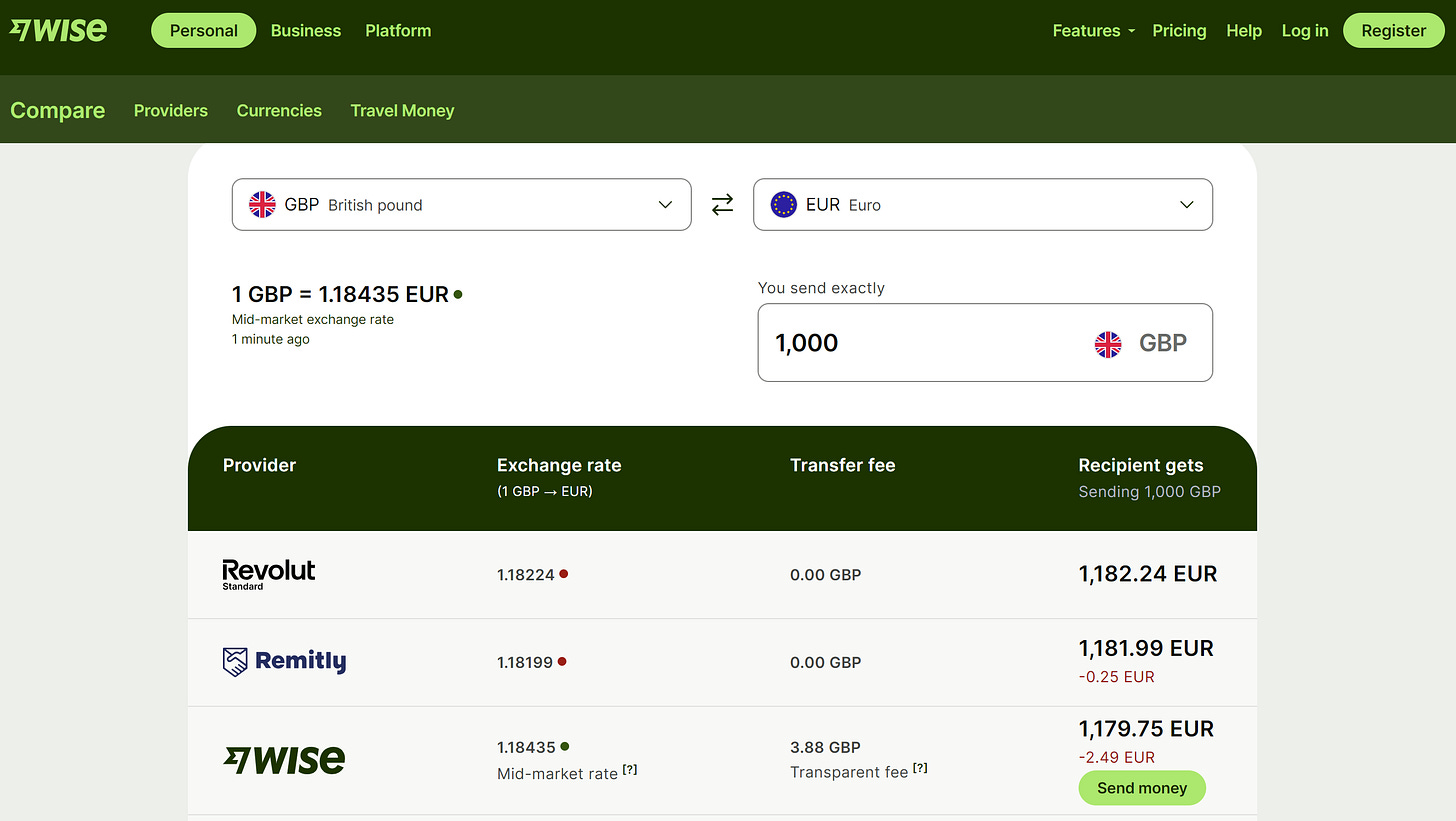

The accumulation of smaller improvements in price, speed, and service created a multiplier effect strong enough for Wise to become the world leader so quickly. Additionally, Wise has consistently offered full transparency on its website, even in cases where it is not the cheapest provider:

Some traditional FSIs have also gained market share, albeit more slowly, due to incremental improvements over their traditional peers. For example, Progressive Insurance's advancements in UX and data analytics more than doubled its market share in the US consumer auto insurance market between 2008 and 2023. Similarly, Capital One's expertise in underwriting higher-risk consumers, aided by acquisitions, has made it a top-10 retail bank in the US just 12 years after its founding.

However, FSIs typically launch new products without significant differentiation for their target segment. For example, despite the failure of large US retailers to launch their payment wallet a decade ago (MCX-CurrentC), large US banks are now attempting their own wallet, Paze. In the initial roll-out, banks offer no incentives and provide questionable differentiation for customers:

Instead of differentiation, large banks, in line with their worst media, court, and political stereotypes, have decided to automatically enroll customer credit and debit cards into Paze, leaving it to customers to opt-out.

The more interesting case of differentiation comes from embedded finance and technology vendors serving FSIs. Their primary focus is on convincing the FSI C-Suite that their solution delivers a clear ROI. The good news is that almost every notable vendor provides impressive ROI-related metrics to strengthen their case.

The bad news is that much of this data is unverifiable and typically presented as "up to," reflecting only the best-case scenario. This recently sparked a rant from Ron Shevlin, who criticized some well-known vendors for making outrageous ROI claims. He rightly pointed out that ROI-related estimates can vary significantly depending on the client's specific situation and the timing of the calculations.

The reality for many embedded finance and technology vendors is that they often don’t know the true accuracy of their ROI claims—and worse, they don’t seem to care. Over the years, out of intellectual curiosity, I’ve offered to conduct a free ROI estimate for vendor C-Suites or their PE/VC owners, only to be met with a consistent "no."

To be fair to the vendors, some of the mediocre ROIs stem from FSIs not fully utilizing the products after purchase. However, wouldn’t it still be valuable to know when a solution is profitable or losing money for clients? As Wise demonstrated with consumers and Ramp with business clients, building a product focused on saving users money is the simplest way to drive hockey stick growth and potentially become an industry leader.

Some FSIs Conflate Organizational Design with Operating Model to Avoid Accountability

As we've often discussed, everything FSI executives need to know about the most effective operating model can be learned from how Amazon operated two decades ago, Netflix 15 years ago, and Spotify a decade ago. No newer, more effective model has been invented since, and every leading FSI and fintech is moving toward that end state. Whenever they stray from this path, they inevitably return to those original principles.

Thus, as part of their digital transformation, FSIs should focus on gradually evolving their operating models toward this target state, while tracking their progress in achieving higher maturity. Interestingly, FSIs rarely track the transformation itself, instead focusing on metrics like the number of digital widgets and users, as seen in TD Bank's 2023 annual report:

The reason is simple—transforming the operating model requires FSI executives to learn how to operate in a fundamentally new way, which is very challenging. Launching new digital products or moving an app to the cloud is much easier, and even better, customer shifts to digital channels happen organically. It's also simpler to create a digital-adjacent organizational model, hoping that putting people in the right boxes will lead to effective governance and collaboration.

But that rarely works, as TD Bank recently learned, expecting to spend $3-4 billion to settle U.S. anti-money laundering probes. At a recent industry conference, TD Bank’s CEO Bharat Masrani expressed his surprise that organizational design alone did not create accountability: “The big lesson is you can’t take anything for granted.” The bank now plans to deepen it:

After “bad actors were able to exploit the bank,” Masrani said Toronto-Dominion needed to “deepen accountabilities for such types of risk” throughout its front-line staff as well as among those working in control and audit functions. The goal is to “make sure folks understand this risk right through the organization and act with urgency,” he said.

TD Bank has taken some standard actions, such as firing more than a dozen employees for code-of-conduct violations, replacing around 10 senior legal and compliance staff, and cutting pay for others. But the real question remains: how will TD actually instill a sense of urgency in its employees when the entire organization has been complacent about stopping large-scale money laundering through its U.S. branches for over a decade? If previous turnover, organizational changes, training, and "risk culture" initiatives failed, what will be different this time?

The answer is unclear. The primary excuse for complacency seems to be around specific individuals and the bank's sheer size, as CEO Bharat Masrani pointed out: "It’s easy in a bank of our size to sometimes not look at accountabilities as clearly as we should." However, there's been no mention of how executives plan to operate differently, such as building cross-functional alignment and spending more time on the ground to embed new behaviors until they stick. Ironically, fostering such a culture in a larger FSI might be easier than in smaller, more hierarchical organizations, where top-down management is the norm.

The common overreliance on organizational design and talent—rather than hands-on strengthening of operational capabilities—is often justified by a quote from Lee Iacocca: “I hire people brighter than me and then I get out of their way.” In reality, this phrase has become a crutch for FSI executives who don’t want to manage and expect their teams to level up on their own or with help from HR or consultants. This trend has been exacerbated by blaming younger employees, portraying them as constantly complaining or exhibiting odd behavior, rather than addressing deeper issues of leadership and accountability.

We know this is an excuse because it's nearly impossible to find a group that complains more than FSI executives themselves. Complaints about direct reports, bosses, peers, culture, and vendors are so normalized that they've become part of standard political maneuvering. I once attempted to cancel a standing meeting with FSI executives where no decisions were made, only to have them demand its reinstatement. They openly admitted needing the meeting as a venue for pure venting in addition to a similar meeting they had without me.

What distinguishes younger employees is their reduced materialism, largely due to a comfortable upbringing in a prosperous economy. They seek more than just a paycheck—they want a mission, collaboration, and personal development. This necessitates genuine management from their superiors. However, the latest approach FSIs like Synchrony are taking to improve culture is offering an on-site therapist through a third-party firm:

The company earlier this year began offering free in-office sessions. On Synchrony’s Stamford campus, the therapist works from a serene space behind frosted glass on the first floor of a little-trafficked building. Initial appointments last an hour; she then offers 45-minute follow-ups.

Like relying on mantras like "It's Okay Not to Be Okay," offering therapy sessions can make struggling employees less resilient and negatively impact overall culture. Instead, effective FSIs analyze the root causes of operating model issues that drive mental distress among employees. They often find that responsibilities are unclear, expectations are misaligned, and managers act only as mentors.

As FSIs address these root causes, they can advance to the next level of their operating model toward the singular target state. With each evolution, they will be better equipped to tackle the expanding list of threats, from traditional issues like money laundering via cash deposits to newer challenges such as crypto ATM scams.

A more effective operating model will also enable financial services and insurance companies to better capitalize on new business opportunities. However, the outcomes are more complex, as even the most capable executives cannot salvage a flawed business model. This limitation was highlighted in the recent viral discussion about “Founder Mode,” reignited by Paul Graham’s essay on Airbnb’s founder, Brian Chesky, and his intensive management style that he had to re-learn:

And how has Airbnb performed after Brian’s return to “Founder Mode”? Its stock has lagged behind its century-old competitor Marriott, and in the last quarter, revenues grew at similar rates but with much lower profit margins.

Hence, the right sequence for FSIs is to prioritize profitable and sustainable business models, and then select the right operating model to support them, without relying on organizational design and hiring alone to make it work. And skip culture training and employee therapy sessions.