GenAI! What Is It Good For? Absolutely Something

Also in this issue: Things Just Ain’t the Same for FSI CEOs

GenAI! What Is It Good For? Absolutely Something

Two and a half years after the most exciting technological innovation of our lifetime — the public release of ChatGPT — it’s almost nostalgic to recall the early expectations among FSI experts and executives. Predictions swung from an imminent Skynet scenario to mass job displacement. Thankfully, talk of "AGI" has faded, and the stocks of so-called “AI-native” disruptors remain down 80% or more from their highs.

One of the most advanced data-driven FSIs, Progressive Insurance, recently announced plans to hire 12,000 new employees. Which functions can’t be scaled with GenAI? Roughly 70% of the open roles are in Claims, many targeting junior staff without advanced analytics skills. With the abundance of organized and first-party fraud, FSIs aren’t ready to trust GenAI with final decisions on losses or negotiations with counterparties anytime soon.

This doesn’t mean large FSIs are slowing their growing investments in GenAI. On a recent earnings call, The Hartford CEO Chris Swift not only emphasized AI as a driver of growth but, more unusually, committed to leading the industry in AI implementation:

“And then, of late, everyone’s been talking about AI, and I’m not going to talk about it in a great detail, but we got three main areas we’re focused on, claims, underwriting and operations. And we will lead the AI implementation for the industry.”

Among leading fintechs, GenAI’s favorite impact area is customer support. Klarna, gearing up for its IPO, has been especially vocal, citing a 30% revenue increase while cutting its workforce by 20% through AI implementation. In its recently published 2024 annual report, Revolut claimed only a modest increase in customer support costs, despite nearly 40% growth in its customer base, crediting GenAI for the efficiency gains:

“In 2024, generative AI had a significant positive impact on our cost structure, particularly in traditionally labour-intensive areas like customer support. Despite a substantial 38% growth in our customer base, we managed to limit the increase in customer support costs to only 5%.”

There’s no conclusive independent evidence at scale proving that GenAI chatbots outperform human specialists in persuading customers to take actions they’d rather avoid. That makes a recent McKinsey claim about Asian consumer finance companies achieving 2–3x improvements in collections “self-cure” rates after switching to bots particularly interesting:

“Also, gen-AI-enabled bots can provide a completely digital channel for customers who might resolve their late payments without the involvement of collections staff. The bots can send reminders and suggest solutions, adapting their scripts in real time based on customers’ responses. Players in Asian markets have seen two- to three-times improvements in “self-cure” rates, with 20 to 30 percent lower costs per account.”

The most popular use case among traditional FSIs is making engineers more efficient. CEOs love this because it lets them announce big gains in release velocity and IT efficiency without needing to wade into the technical details.

Moving beyond the qualitative remarks of 2023–2024, an increasing number of large FSIs are now claiming quantitative gains from coding assistants. While JPMC remained cautious with an “up to 20%” improvement in engineer efficiency, Bank of America recently cited 20% and above. In an interview with CIO Online, Hari Gopalkrishnan, head of consumer, business, and wealth management technology at Bank of America, highlighted this as the key outcome of the company’s $4 billion AI investments:

“The bank is already capitalizing on generative AI applications and pilots that are now beyond the proof-of-concept phase, Gopalkrishnan says. Developers, for instance, are using a AI-based tool to assist with coding and have seen efficiency gains of more than 20%, the company says.”

GenAI can boost engineering productivity in FSIs by 20% through automated code generation, refactoring, and testing. The simplest way to monetize this boost for a typical FSI with slow-growing revenues would be to reduce engineering capacity by 10%. However, the number of engineering staff has become a vanity metric in the industry, with many hoping to achieve a valuation multiple akin to that of a technology company. As a result, many FSIs are hesitant to cut staff, and engineering roles often remain the top open position.

An ideal monetization strategy would be similar to leading fintechs, using productivity boosts to launch even more new digital products and accelerate revenue growth. However, shipping fast is only a competitive advantage if the success rate is 80% or higher. If half of the product launches fail to impact the FSI’s revenue, it becomes a waste.

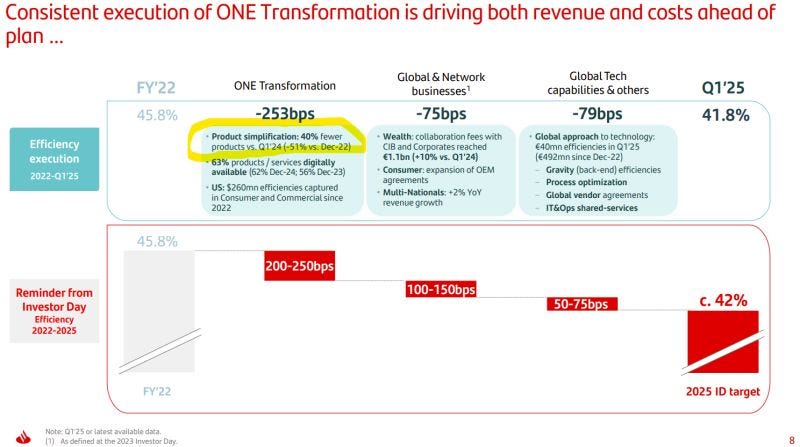

Even without GenAI, most advanced global FSIs struggle with operating models that can effectively prioritize high-ROI new product initiatives amidst a flood of potential releases. For example, Santander cut 40% of its products last year without any noticeable revenue impact.

On top of limited revenue upside and unclear realization of efficiency gains, GenAI has opened a Pandora’s box of security vulnerabilities. Patrick Opet, JPMorganChase’s Chief Information Security Officer, recently made waves with a surprisingly candid open letter to vendors, requesting that they reprioritize security, placing it equal to or above launching new products. His public call to action followed an internal security assessment that exposed the paradox of GenAI. The "generative" feature, by design, is meant to be a black box, unlike its predecessor, a more predictable machine learning model:

78% of enterprise AI deployments lack proper security protocols.

Many companies cannot explain how their AI makes decisions.

Security vulnerabilities have tripled since the mass adoption of AI tools.

Without the engineering talent and discipline of leading fintechs, traditional FSIs should consider GenAI’s role in software development as if they hired an army of junior engineers. They are not necessarily useless, but require micromanagement to add value without jeopardizing the franchise. In other words, the generated code is only as good as it is reviewed and finalized by top-notch engineers. Their numbers become the first bottleneck, followed by a limited number of digitally savvy business owners who can guide engineering teams on which features will create the most significant business impact.

Amid the GenAI hype, hearing an ultra-programmatic perspective from an FSI executive, especially a Chief AI Officer, is rare. In a recent interview with CIO Online, Richard Wiedenbeck of Ameritas stressed the importance of realistic expectations and a targeted, hands-on approach. GenAI is undoubtedly useful for something, but FSIs won’t capture financial impact if they’re hoping for a self-propagating breakthrough. Wiedenbeck shared three key lessons:

Rather than being a brand-new discipline, GenAI is just the latest tool in the decades-long business process reengineering of FSIs.

The only true success metric is demonstrated business value: he, his team, and all counterparts must always remain hands-on with business-driven use cases.

A small Center of Excellence of GenAI experts is more effective than training hundreds of data analysts for mediocre knowledge gains.

Things Just Ain’t the Same for FSI CEOs

Without bothering with real digital transformation, the CEO job is an attractive gig. You get paid a lot to guide senior executives, promote the company to the media, and share inspirational war stories with employees. Even when CEOs get personally involved with the details, it’s usually something high-profile like M&A or partnerships. It’s also a safe role since board members are rarely independent enough to force CEO departures. Financial services CEOs, in particular, enjoy the longest average tenure across industries, at over 8 years. For larger players, that number rises to 11 years.

Real digital transformation, on the other hand, is all about the details. With each step forward on the digital evolution journey, the operating model becomes more cross-functional, autonomous, and moves at different speeds. This contrasts with the natural human preference for the stability of siloes, top-down controls, and uniformity. The CEO must first learn this completely new way of operating at the beginning of each climb, then coach their reports, and help them coach theirs.

The CEO role is already tough enough when it involves dragging everyone to the mountain from day one, even when everyone is a willing participant. Imagine a more typical scenario, where the company is stagnant or losing effectiveness—now the CEO has to jump-start or even reverse the momentum. This is incredibly difficult, not just for CEOs of traditional FSIs but even for world-renowned founders of digital natives.

Brian Chesky constantly speaks about his transition into "Founder Mode" at Airbnb in 2020. Jack Dorsey similarly became hands-on with Block in 2023. Neither has changed the company’s trajectory. While the stocks of top incumbents in their respective markets have surged, Airbnb and Block have stagnated.

For CEOs of traditional FSIs, real digital transformation can feel overwhelming. Times are changing, and they are aging. So, instead of focusing on transformation, they replace it with “modernization.” Rather than rethinking the operating model, it's easier to continue automating manual processes while upgrading IT systems.

Another common tactic is to remove themselves from the details of digital transformation by creating another C-suite level. The most popular combination is merging Operations and IT under one executive. Many FSIs have tried this over the last decade, only to reverse the decision later due to its negative impact on digital transformation. A high-profile example is DBS, a Singaporean bank once seen as a digital-transformation pioneer, until its systems started failing, prompting a stringent regulatory response.

In the post-mortem analysis, DBS acknowledged that the rapid expansion of operational processes and underlying technologies posed a significant risk without adequate checks and balances. Having the head of Operations also oversee Technology made it less likely for this executive to hold both a) technology groups accountable for the resilience of new systems, and b) operations groups accountable for a manageable pace in introducing new processes. Ironically, the most recent example of such a tactic to advance digital transformation comes from another bank headquartered in Singapore.

The challenge is even more daunting for CEOs of smaller FSIs. They are often overwhelmed by technical debt and constrained by small budgets. Modernizing technology with top vendors could be prohibitively expensive, not to mention the constant struggle to get their attention. Smaller vendors are more affordable and approachable but lack many essential features. Building in-house is often too risky—small FSIs struggle to acquire strong engineering talent and never know if a few digitally savvy employees will leave after building a custom solution.

Hands-on accelerators are becoming increasingly popular for CEOs eager to accelerate digital transformation in such an environment. Local and nationwide associations, along with venture funds, are not only investing in fintechs focused on small FSIs but also preparing them for smoother onboarding. They even offer scaling assistance and training to FSI employees, making the transition more manageable.

The challenge with this approach remains the lack of internal talent competent enough to avoid creating a Frankenstein-like architecture. As more fintech niche solutions are implemented, connecting them to core platforms requires more middleware, and making them API-friendly demands strong engineering talent — talent that is already stretched to the maximum. Ideally, the accelerators would also provide multi-year, hands-on coaching to executives and employees, but no one has yet figured out the economics of such an integrated service for small FSIs.

So, what is the best course of action for CEOs who want to accelerate digital transformation without wishing to become Nik Storonsky? FSIs can still achieve respectable results if the CEO learns to:

Maintain 2-3 reports committed to leveling up operational muscles and ensure each has 2-3 reports dedicated to the same goal.

Ruthlessly prioritize digital initiatives to maximize business impact, while optimizing for the available capacity of top digital talent.

Ensure that every initiative both creates new digital capabilities and improves the underlying operating model and technology architecture.