To Accelerate Growth, Should FSIs Overinvest in Digital Transformation or Traditional Advertising?

Also in this issue - Customer Data: FSIs' Greatest Asset and Biggest Minefield.

To Accelerate Growth, Should FSIs Overinvest in Digital Transformation or Traditional Advertising?

It is easy to dismiss the disruptive potential of crypto companies in financial services and insurance. After 16 years, no payment company using cross-border rails has provided volume data on the use cases of repeat customers. Meanwhile, fiat-based fintech and insurtech have made significant strides, capturing market share from incumbents or stalling their growth in niche products.

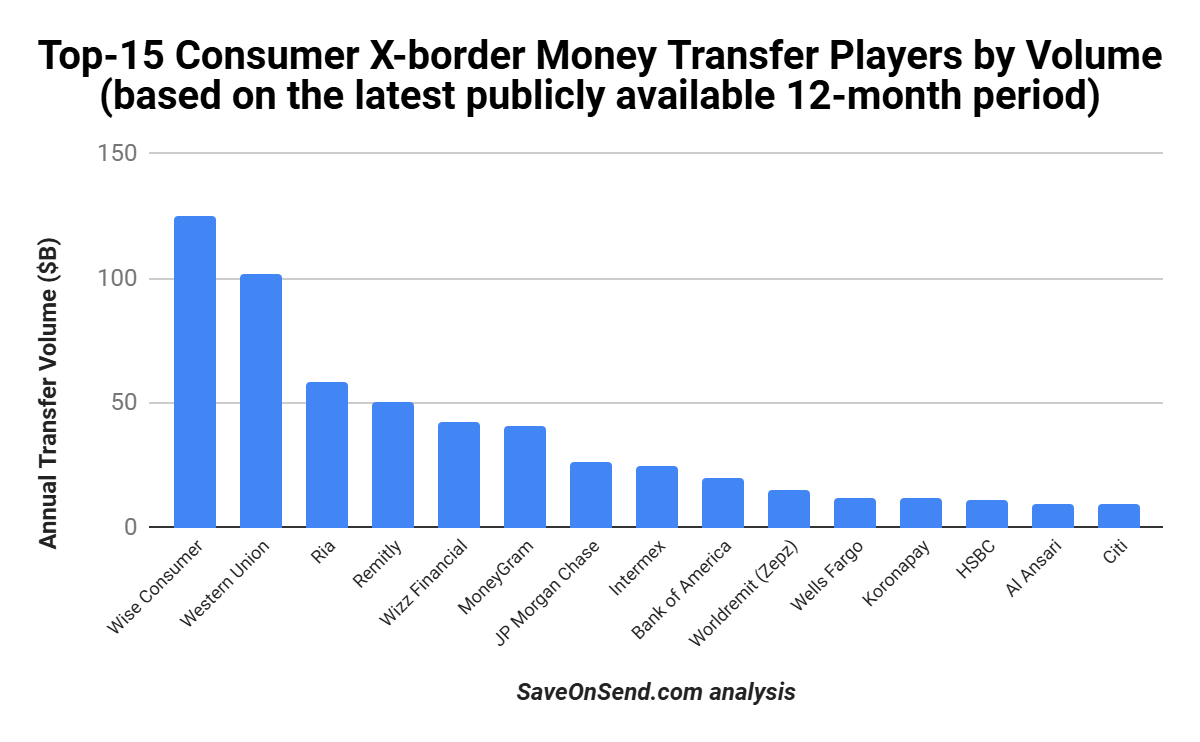

Take consumer cross-border money transfers in 2024 as an example—a clear win for fintech. Banks and traditional players like Western Union and Intermex experienced stagnating growth, while Sigue and Small World went out of business despite the overall market growing at 9% annually. Fintechs are the culprits: Wise and Remitly continued their rapid, profitable growth, securing #1 and #4 global market share, respectively.

In the U.S., a recent PYMNTS survey found that 13% of consumers have a primary account with a fintech bank. While this may not seem significant after over a decade of "fintech disruption," Cash App became a top-10 consumer bank by revenue in Q2 last year, excluding its business and bitcoin products. Unlike incumbents with stagnant revenue, Cash App’s growth has stabilized around 20%, so it could keep moving up in rankings every 3–4 years.

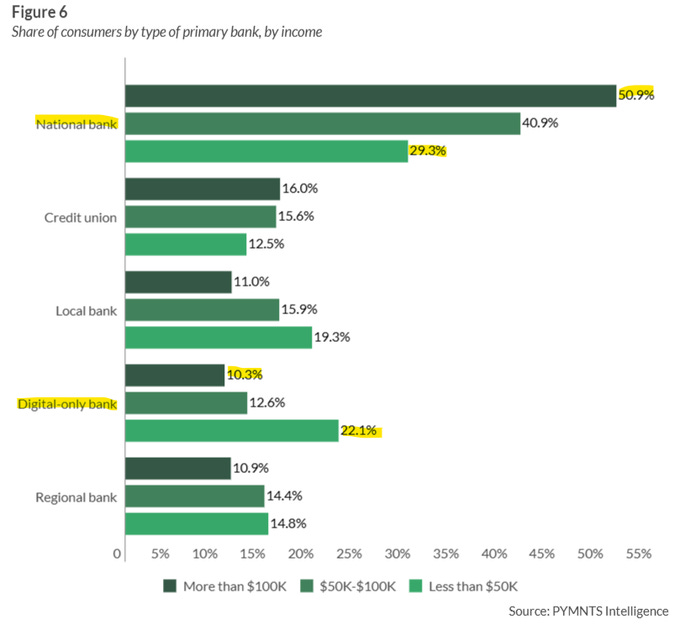

The good news for traditional FSIs is that consumer apathy remains a powerful force. Unlike shopping or transportation, where digital disruption has become the norm, financial and insurance services are perceived quite differently. Consequently, it’s not surprising that most neobanks have gained traction primarily among younger, lower-income consumers, who open primary accounts with neobanks at a rate 5+ times higher than boomers.

For now, incumbents dominate market share across all banking segments, particularly among higher-income consumers, where their lead over digital-only banks is approximately 5:1.

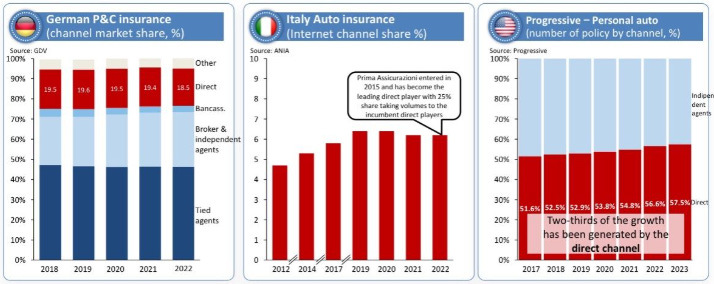

Consumer apathy is particularly evident with risk-based products. As insurance expert Matteo Carbone often reminds us, fears of the demise of incumbents and agents have been greatly exaggerated over the past 15 years. In some Western countries, the direct channel remains the smallest. Even for an insurtech pioneer like Progressive, the agent channel still accounts for 40% of its policy sales:

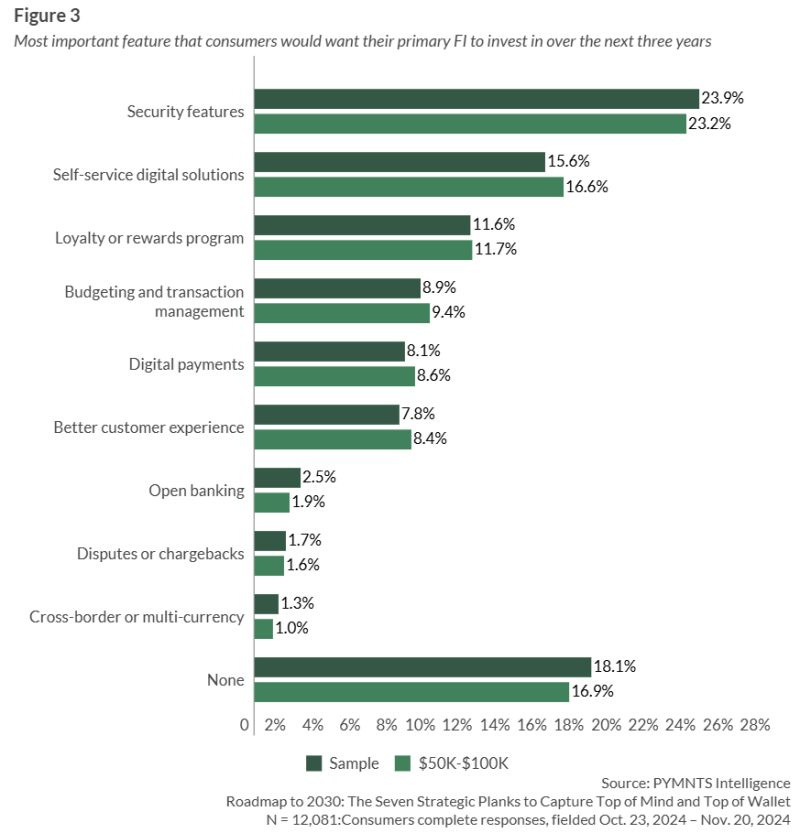

Hence, traditional FSIs pursuing digital transformation to accelerate top-line growth face a dilemma: how can they profitably grow their share of wallet with existing customers or attract new ones? The intuitive answer seems to be launching popular new product features, but this presents two trade-offs. In the same survey, the most requested feature was security, which they expected to receive for free. The second most requested feature was none—essentially, "I’m begging you to stop adding more features."

Fintechs are increasingly in the same boat as traditional FSIs, struggling to find easy growth opportunities. Generating rapid growth at scale through free word-of-mouth remains true only for standout companies like Nubank and Wise. For everyone else, the less differentiated a fintech’s value proposition is from incumbents, the more it will need to rely on traditional advertising to sustain faster growth.

Customer Data: FSIs' Greatest Asset and Biggest Minefield.

The law of unintended consequences is my favorite because it reminds me of chess, where you must think at least one step ahead. For decades, this law has sparked both laughter and frustration in financial services and insurance, as U.S. regulators at the federal and state levels have attempted to limit FSIs' products and fees to protect vulnerable consumers.

These same regulators, who can’t predict financial crises and know how to address them by printing more money, have identified traditional FSIs as the cause of underserved consumers. But what if a consumer segment is using too many financial products? Whose fault is that? Of course, traditional FSIs as well. Essentially, FSIs are expected to offer risk-based products to everyone for free instantly and then ensure customers only use them to improve their financial well-being.

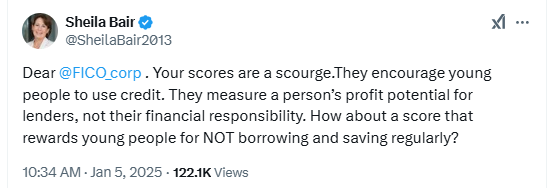

One of the most common victims of traditional FSIs in the U.S. is supposedly young people. The fact that Gen Z is the highest-earning, most saving, and best investing generation seems irrelevant. Recently, former FDIC chair Sheila Bair opined on the collusion between lenders and credit score vendors, claiming they inflict suffering on gullible youth:

You’re probably old enough to remember how, just a decade ago, there were regular articles about the generational trauma young people in the U.S. supposedly suffered due to the 2008 financial crisis. They were said to be so traumatized that the mere mention of the word “credit” would make them nauseous. That victimization was milked to death, and now the narrative is that we need to save young people from more credit.

Apparently, the solution is to limit access to information about consumers’ likelihood to default. Traditional FSIs have faced such data-limiting mandates for years. Frank Rotman, who was Capital One's Chief Credit Officer in the late ‘90s (before the role officially existed), recalls in a 2024 interview that they couldn’t use valuable data points like an applicant’s profession in their underwriting models.

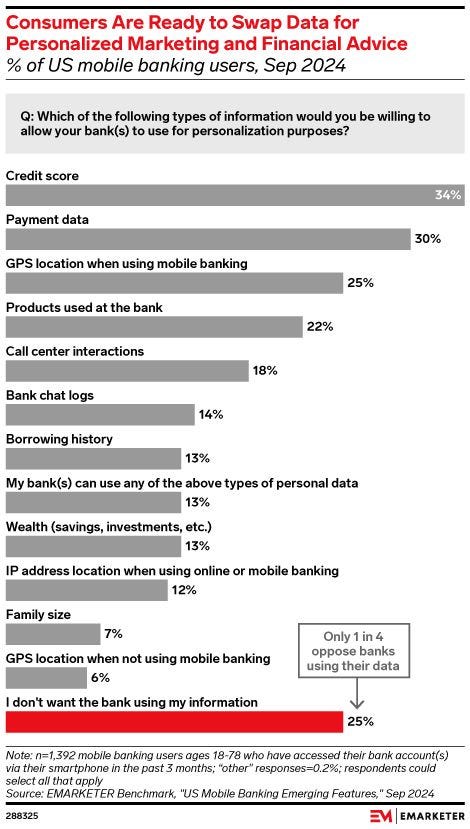

The data usage restraints are especially unfortunate because most consumers want banks to use their information for personalized marketing and advice. Guess which information they are most willing to share with a bank?

A somewhat positive development for consumers in riskier segments is that regulatory focus remains on traditional FSIs for now, giving fintechs a bit more freedom to close the gap. The proliferation of alternative lending products with higher rates and no reliance on credit scores is a suboptimal outcome, but it’s arguably better than depending on loan sharks.

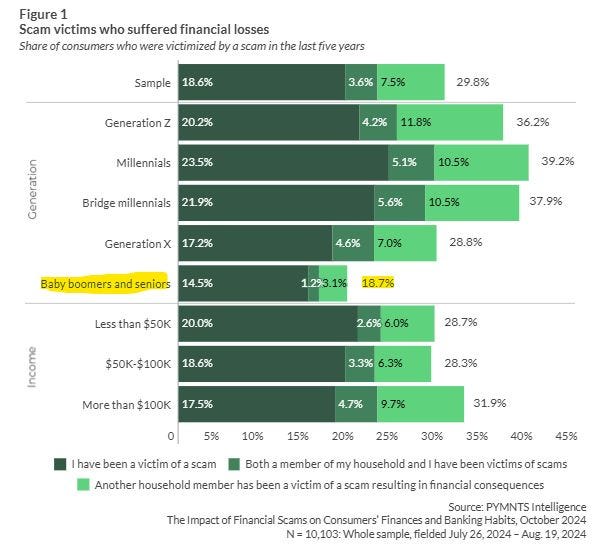

Similarly, when it comes to the pressure of offering either too little or too much credit, U.S. regulators are quick to blame traditional FSIs for using both too much and not enough data. In a recent lawsuit, the CFPB accused top banks of allowing fraud to persist in Zelle, partly by failing to share information about repeat offenders:

Allowing repeat offenders to hop between banks: Early Warning Services and the defendant banks were too slow to restrict and track criminals as they exploited multiple accounts across the network. Banks did not share information about known fraudulent transactions with other banks on the network. As a result, bad actors could carry out repeated fraud schemes across multiple institutions before being detected, if they were detected at all.

Since the U.S. government doesn’t seem interested in imprisoning repeat first-party offenders, maybe U.S. banks should indeed consider creating industry-wide blacklists, especially since the CFPB appears to be supportive. However, such blacklists might show that certain ethnic groups commit financial fraud at rates 5-10 times higher than average. This would expose banks to even bigger lawsuits and accusations of minority discrimination.

It would be tempting to dismiss current U.S. regulators as ideological zealots who will be replaced once Trump retakes office. However, from my recent conversations with FSIs, I've learned that they’re not convinced that restrictions on data usage will be relaxed. Trump has also expressed his negative view of FSIs, proposing cuts of 50% or more to auto insurance and credit card prices.

Digital transformation use cases depend on the ability to extract and apply increasingly broader data sets. However, navigating consumer-centric use cases feels like navigating a minefield, with everyone hoping an FSI takes the wrong step. In a world where FSIs are held accountable for any bad outcome while severely limited in their data use, boomers who don’t care for the internet become everyone’s favorite segment.