How To Fix Unhealthy Tension Between Enterprise and LOB Executives in FSIs,

Replacing Legacy Systems Is The Costliest Mistake in The Digital Transformation of FSIs

How To Fix Unhealthy Tension Between Enterprise and LOB Executives in FSIs

The head of client services at a large life insurance firm began laughing after I told him that the enterprise IT PMO was eager to pilot an agile MVP with his group. 'Agile? They don’t know what it means, and they understand what I do even less,' he said. Ironically, IT executives told me more or less the same thing about him. This chasm is common across financial services and insurance firms, even in well-managed ones. LOB executives complain about Enterprise groups being too siloed, while enterprise executives are frustrated by the lack of LOB engagement.

As a result, financial services and insurance companies are spending billions on consultants and advisors annually to have them act as a buffer between executives and be used as pawns in internal political battles. This buffer is like an expensive marriage counselor for couples who never want to see each other again while trying to win in the relationship at all costs. Since budgets always need to go up, many FSI executives are fine with such ineffective practices and tend to resist when pushed by advisors to collaborate.

As FSI LOBs increasingly realize that digital capabilities are crucial to their success, the requirements for time-to-market and the quality of enablement by enterprise groups are significantly increasing. That leads to higher intensity of mutual complaints between LOBs and enterprise groups, along with the turnover of enterprise-level executives. The serenity of enterprise chiefs (data, architecture, infrastructure, security, PMO), who were previously waited on patiently, is no more.

The enterprise C-suite has been mostly unwilling to downsize its legacy bloat of project managers, architects, and analysts. The head of Enterprise Architecture of a top-5 bank once came to ask for advice on how to keep almost 100 of his architects busy in a new paradigm. I suggested transitioning the best ones to lead shared platforms/apps as software engineers while pushing others to either interview for LOB roles or exit. Coincidentally, we never spoke again, and the bank’s number of enterprise architects has grown. If enterprise-level executives are not willing to transform their operating muscles, it falls to the CEO to drive the change, but how?

The need for the enterprise C-Suite to be more flexible is a comparatively straightforward problem to solve. If nudging by the CEO doesn’t help, a "glass tower" executive could be replaced with someone more entrepreneurial or from a more digitally mature FSI. A much bigger challenge lies in the wide spectrum of digital maturity across LOBs within the same company.

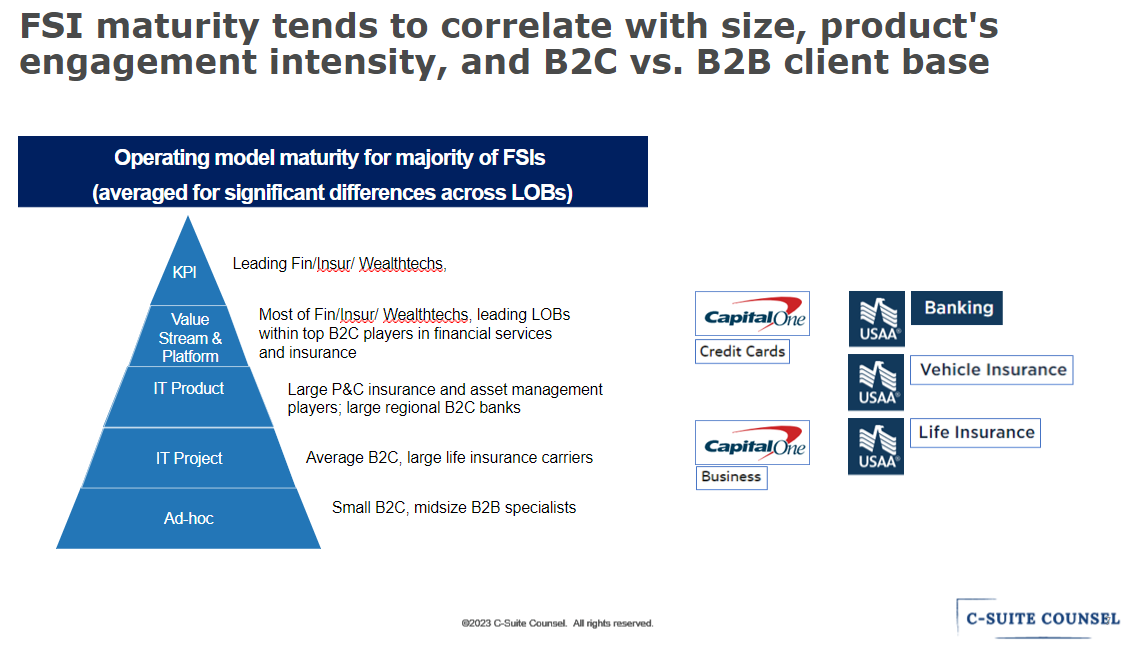

At least in higher-performing FSIs, all LOBs are eager to evolve their digital maturity, albeit at a different pace. In a typical FSI, the extra complication is due to some LOB leaders being content with their current level of data and technology support and not seeing a need to level up. Such variability in digital maturity and desired pace of evolution creates an extremely complex environment to be supported by shared enterprise groups.

In order to provide fit-for-purpose enablement in such an environment, shared enterprise groups have to operate at multiple speeds, two to four, depending on the FSI's size and product variety. This goes directly against a deeply ingrained human preference for reductiveness (aka, a one-size-fits-all operating model). And that is a fundamental root cause of LOB complaints about enterprise groups. If someone in the enterprise C-Suite can't operate at multiple speeds, their group would be suitable for some LOBs but too slow and/or too aggressive for others.

How could CEOs help eager enterprise executives to develop such rare operating muscle? They would need to micromanage through the following four steps for each LOB-Enterprise intersection until the muscle takes hold (or find a replacement):

Own the problem: Stop complaining about LOBs; they make money that pays for enterprise groups. In digital transformation, the enterprise C-Suite's job is to make LOB heads happy at scale.

Provide excellent reactive support: As we discussed in our recent newsletter on the role of the CIO, enterprise executives should aspire to level up their LOB counterparts, but only after exceeding LOB expectations for requested digital enablement. That means holding off on offering a business executive an agile pilot if the enterprise group takes a week to ship a laptop or can't resolve weekly outages.

Offer LOBs to self-select: Every year, ask LOB executives if they are ready to partner on a new digital pilot. Suggest a use case and promise to personally assist with leveling up. If successful, gradually expand the number of concurrent pilots and their complexity.

Relinquish ownership for one-offs: Also every year, suggest that LOBs accept full development ownership over solutions not used by other lines. Promise to personally assist with the transition of knowledge and staff.

In the end state, LOB leaders would assume full ownership of their own applications while enterprise groups focus on shared digital services (see the example of a Sales-related use case in this newsletter). What path would your FSI pursue this year: short-term satisfaction from complaining or long-term joy from mastering a sophisticated operating model?

Replacing Legacy Systems Is The Costliest Mistake in The Digital Transformation of FSIs

In a sea of examples of how not to approach digital transformation, it’s always a happy day to come across a clever FSI. A consumer P&C subsidiary of a global FSI was implementing Guidewire to digitize agent experience, but instead of a typical horror story, the project was going well. The first positive sign was a customer-facing website right after launch - it had a couple of workflow issues, was released in just one state with limited functionality, and the issues were fixed in a couple of weeks. I asked the CEO shortly after, “Why didn’t you big-banged it like most of your peers?” He said, “Because it doesn’t work.”

For a year afterward, I was telling other P&C carriers about that anonymous example of an effective core system replacement: an integrated team, a few local expert contractors, end-user engagement, one-state-one-functionality releases, and focus on change management. But when I checked in again with that P&C, the modernization went off the rails. I was shocked to hear about huge overruns and angry agents. “CEO got promoted, and the new one wanted to finish it faster, so we engaged 60 people from a low-cost off-shore vendor.” After decades of modernization disasters, including by this very same company, the collective memory of best practices was wiped out. Why?

The most honest response came from a CFO of a commercial insurance LOB. They were just starting to replace a legacy SME application with a hybrid (in-house+API) solution and already made every single mistake in a book (2-year release, 5-tier governance, 100s of offshore SI staff, untested vendor solution, no end-user engagement, etc). I asked CFO if she realized that this project would be a massive failure. “You are probably right, but this is the only way we know how to get things done.”

It's easy to blame the wasteful phenomenon of big-bang legacy replacements on the exquisitely persuasive platform and SI vendors who are ecstatic about huge bonuses and guaranteed employment. However, it is actually the FSI C-Suite executives who usually push for this approach. Their mindset hasn’t changed much since the 90s, but now it is called "agile" due to a much higher frequency of meaningless internal updates. In my experience, Gartner and Info-Tech Research Group analysts advise clients against such a strategy, but often to no avail. Here is how Navy Mutual’s IT executive, Peter Meyers, recently described the rationale for massive modernization:

Meyers explained that he knew that every existing process would need to be assessed and analyzed to achieve a high-tech vision for the company… In Navy Mutual's assessment, 99 systems were identified as key technologies, but presented a challenge as "each had been implemented over different years and at different points," stated Meyers. The disjointed technological ecosystem presented many challenges, Meyers added. The insurer was left to determine how to best approach the overall transformation.

A relatively small life insurance company wants to be “high-tech” via “overall transformation.” It’s as if Toyota Corolla wanted to compete in Formula 1 by replacing all major parts but keeping the regular Toyota staff for driving and maintenance. As we discussed in this newsletter about no-code solutions, the main reason for failure in replacing a legacy app is implementing it too rapidly, so the end-users can't catch up to new features. Now imagine doing this to dozens of apps, all at the same time, and with overlapping end-users.

What if you are an FSI executive who has the flexibility and grit to try a proven method? Then, the required mindset for legacy replacement is straightforward: no "digital beliefs." Don't treat "digital" as a cult with unquestionable rules: "modernization," "cloud-first," "API-first," "full stack developers," etc. Instead, embrace the harsh reality of upset end-users, disjointed staff, cost overruns, and misaligned incentives with 3rd parties; question every planning step through a skeptical lens:

By conducting the steps above, FSIs frequently discover that a microservice replacement would be more expensive and require more internal hand-offs, while business benefits are not clearly larger. That is, once a business owner appreciates how much involvement is required from them, many will select themselves out ("It's not as much of a competitive differentiation as I thought initially"). Even in the best-managed fintechs like Wise, monolith replacement is a never-ending bottom-up process. While the ultimate target state for all FSIs is singular (see this newsletter), the journey to that hyper-modular future is arduous, and leapfrogging is very costly.