If KYC=CYA, No Amount of Digital Transformation in FSIs Makes a Difference

Also in this issue: Why Is Scaling Natural for Fintechs but Elusive for Traditional FSIs?

If KYC=CYA, No Amount of Digital Transformation in FSIs Makes a Difference

Money laundering is good for business—at least for some. While plundering resources by government officials is disastrous for citizens of poor African countries, it's a boon for consultants, lawyers, realtors, and bankers in places like London, who launder those proceeds. They enjoy the best kind of business—rich, undemanding customers. An estimated $1.6 trillion is laundered annually, with the occasional spoiler being the U.S. government. Through its control of the dollar and FBI resources, it annoys its more lax counterparts in the UK, Switzerland, Singapore, and elsewhere to stop accepting easy money.

Most FSI C-suite executives treat anti-money laundering (AML) as a black box that can cause financial, reputational, and legal problems. The ideal scenario is to hire people to “handle all that” while providing “tone at the top” support to demonstrate senior leadership's commitment to complying with AML regulations. However, this hands-off mindset carries significant risks, as TD Bank recently discovered. The U.S.’s tenth-largest bank will pay $1.4 billion to the DOJ, $1.3 billion to FinCEN, $0.5 billion to the OCC, and $0.1 billion to the Federal Reserve. Even more unusually, TD will be forced to cut its assets by up to 7% annually if it fails to implement the resolution plan.

For over six years, TD failed to monitor 92% of its transaction volume, instructed its front-line employees not to file suspicious activity reports, and ignored a flood of transactions in places like Colombia, where it had no legitimate business. The bank, known for its legendary customer service, apparently thought that included catering to associates of Chinese triads and Mexican cartels.

The real irony is how long it took U.S. regulators to notice these pervasive issues and take action (unfortunately, we can’t fine or imprison them for incompetence). It doesn't seem like the OCC, FinCEN, FDIC, FINRA, or SEC run regular automated checks on compliance activities across financial institutions to notice if they monitor transactions for money laundering, fraud, or insider trading.

Though TD Bank is an extreme case, it’s not unique. FSIs have short-term incentives to avoid scrutinizing the source of funds too closely, and U.S. regulators often lag. This likely means other major FSIs are currently overlooking a significant portion of their transactions. More relevant to our discussion about digital transformation in FSIs is that fixing AML is much harder than it seems—and not for the reasons typically cited.

Regulators could blame the banks' “flat cost paradigm,” as throwing more money at problems is the default approach for government agencies. TD Bank, after spending half a billion tightening its AML procedures, points to its vast size as the issue. But how many employees does it take to notice missing transaction monitoring? TD Bank’s internal audit should have picked up on the lack of basic transaction monitoring and outdated alerting scenarios, let alone any independent assessor.

If you think your large FSI is immune to this, think again. Chances are your compliance department is equally disorganized, with its primary incentive being to sweep problems under the rug (aka "CYA"). A compliance leader at another top-10 bank described their operating model like this:

Enterprise and divisional siloes with no workload balancing, leaving some teams starved for capacity while others wait weeks for assignments.

Multiple contracts with large outsourcing firms in the U.S. and India, which subcontract AML work to specialist boutiques since they lack in-house expertise.

Information flows only upstream, leaving frontline teams mostly unaware of committee decisions. When upstream groups have questions, it can take weeks for frontline experts to receive and respond through the chain.

Citi recently paid $136 million in fines after failing to fix data management issues it had promised to address in 2020, after already paying $400 million in penalties. Like TD Bank, it’s not for lack of spending. Citi spends proportionally more on technology than most of its peers:

Business Insider recently interviewed 14 current and former Citi employees to understand why their issues haven’t been addressed yet. While the main story was focused on Anand Selva, the bank's COO, Citi’s notoriously opaque operating model was also cited as a key root cause:

Eight employees told BI that they were surprised that Selva was made the head of the Transformation given that he had never held a leadership role in technology or compliance. They described Citi's culture as a cliquey environment that rewards managing up over results, noting that the COO promotion followed dismal performance for the wealth unit he oversaw.

It's tempting to believe that technology, especially generative AI, has a major role to play. However, in my discussions with FSI C-suite executives, there’s been more eye-rolling lately. The optimism of late 2022, when generative AI was expected to overcome unstructured data and siloed operating models, seems to have faded.

If cutting-edge technology were the ultimate solution, advanced players like Starling Bank wouldn’t have recently been fined £29 million by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority for "shockingly lax" controls. Similar to TD Bank's case, Starling took about six years to realize they were screening customers against only a fraction of the full list of individuals subject to financial sanctions.

Starling’s financial sanction screening controls were shockingly lax. It left the financial system wide open to criminals and those subject to sanctions. It compounded this by failing to properly comply with FCA requirements it had agreed to, which were put in place to lower the risk of Starling facilitating financial crime.

As we've often discussed in our newsletters, solutions to persistent problems are rarely costly or intellectually complex. The real culprit is usually a lack of alignment in the C-suite when following the proper decision sequence:

Business model → Operating model → Technology model

FSIs that successfully tackle money laundering start by viewing compliance as a business differentiator. In these organizations, business executives actively engage in AML strategy, and the AML staff is integral to product development and rollout. Choosing the technology tools to maximize the scaling of the AML function is the final decision.

Once KYC stops being CYA, the AML staff feels more empowered, and their business counterparts finally understand their responsibilities. The real question is whether your FSI's C-suite genuinely desires this clarity and whether your head of AML seeks that level of accountability. Digital transformation cannot compensate for this.

Why Is Scaling Natural for Fintechs but Elusive for Traditional FSIs?

A quarter-century ago, Amazon taught us the meaning of scaling. Quarter after quarter, the startup operated at a loss, driving analysts mad with typical responses about long-term investments in scaling its core business and launching new ventures. By 2003, however, its variable margin contribution became so high that no amount of investment could negate it, leading Amazon to profitability—and the rest is history.

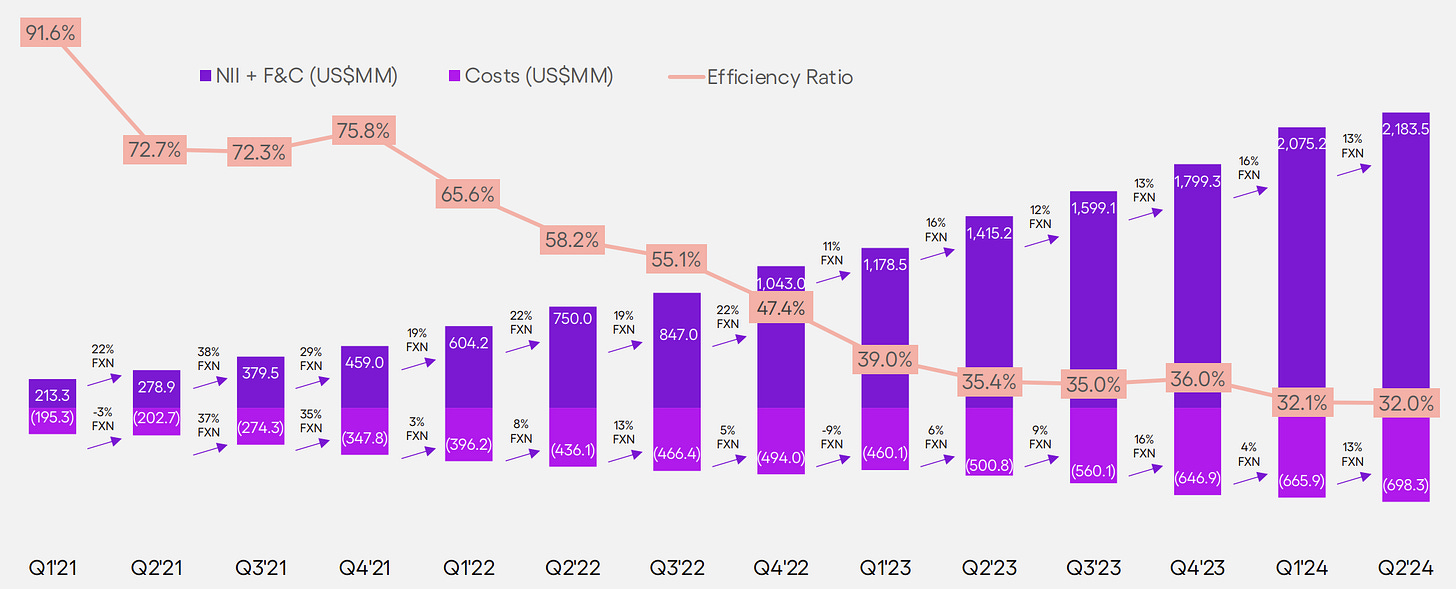

The same scaling pattern is evident with leading fintechs. They often operate at a loss during their initial years, necessitating massive VC funding, and typically break even after five to seven years. A relentless focus on automating every step with software creates scale with relatively fixed expenses while rapidly growing the top line. This results in spectacular efficiency ratios, with seemingly no end to further improvements, as seen in the case of Nubank:

To be fair, the majority of fintechs fail to reach or sustain scale, often going out of business when VCs suddenly focus on positive cash flow, as happened in 2022. Consumer insurtechs have struggled to scale, inadvertently competing in an industry that is barely profitable to begin with, with the stock prices of even the best players down 90% from their highs. Even for the top fintechs, Nubank’s rapid top-line growth at such a scale is unique. Many successful fintechs tend to settle around 20% growth in revenue and 15% in expenses.

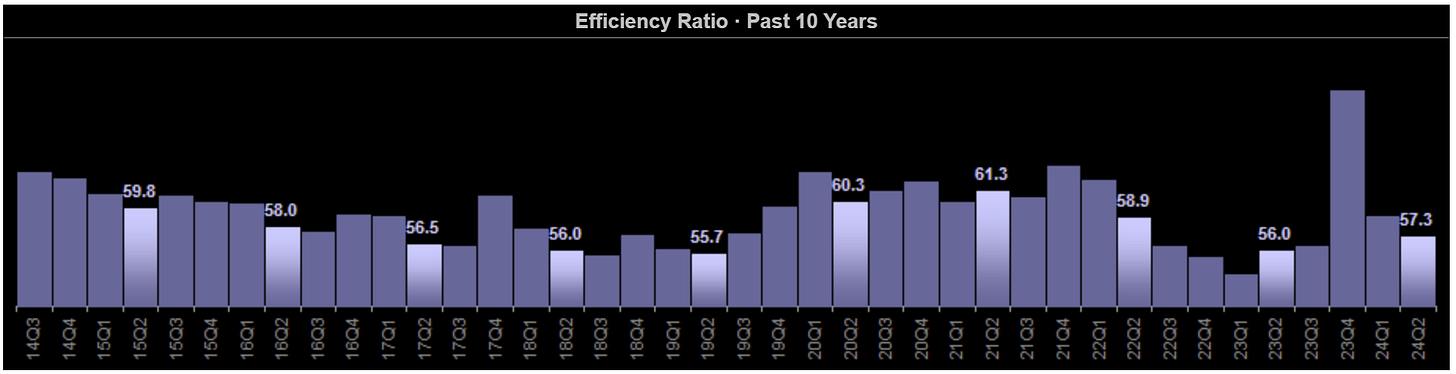

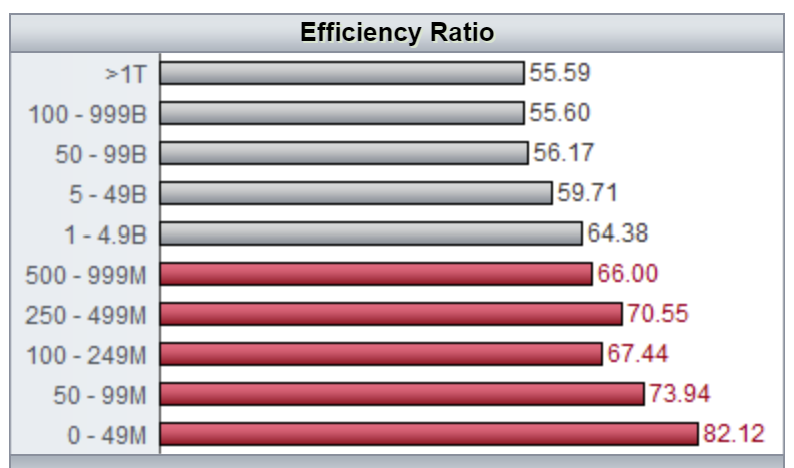

Traditional FSIs would love to be considered on par with fintechs, or even technology companies, but their proof of scaling is much less straightforward. Over the last decade, a typical FSI has roughly maintained the same revenue and expenses, adjusted for inflation. This has resulted in a somewhat unchanged efficiency ratio, as illustrated by the BankRegData site for the top 100 U.S. banks:

Scaling traditional FSIs is made even more elusive by the apparent lack of size advantage. As we often discuss in our newsletter, in financial services and insurance, bigger is not necessarily better. In some cases, larger FSIs, despite being more advanced users of technology, get stuck in the most perilous stage of digital transformation: IT Product. At this stage, product teams may churn out many more features and keep the business more involved, but without guidance from business owners, this often leads to massive waste.

With interest rates high, FSIs have been able to spend a record percentage of revenue on technology without impacting profits. However, the lack of scaling will be hard to conceal as Central Banks begin cutting rates. This was evident in the recent Q3 results announcements from firms like JPMorgan and Wells Fargo, which reported year-over-year declines in revenues and profits. Consequently, analysts have intensified their scrutiny of the timing of ROI.

In response, JPMorgan’s CEO, Jamie Dimon, essentially conveyed during the recent earnings call, “Trust me or get out.” He stressed that expenses should be viewed as an “investment,” emphasizing three priorities: private bankers, branches, and AI.

“You call expenses very often. I call investments… We're adding private bankers in international private banking… We've added some branches across the United States of America. We think there are huge opportunities in the innovation economy that takes bankers and certain technologies, stuff like that.

Our goal is to gain share, and everything we do, we get really good returns on it. So I look at that, these are opportunities for us. These are not expenses that we have to actually punish ourself on. And we do get, and we show you kind of extensively, you know, the cost and productivity on various things.

And also AI is going to go up a little bit. And I would put that as a category that's going to generate great stuff over time.”

With JPMorgan’s stock at an all-time high and up 30% year-to-date, investors seem willing to trust Jamie Dimon, much like VCs trust fintechs in their first five years. Moreover, in the worst-case scenario, an FSI may not achieve scaling but can always improve efficiency through good old-fashioned cost-cutting.

Recently, different UK players, such as Metro Bank and HSBC, announced plans for significant cost cuts. To be fair, even a visionary leader like Jamie Dimon won’t come close to Elon Musk’s feat of cutting 80% of Twitter’s staff while launching more features. However, a 10% reduction would be an easy task for any FSI CEO.

While buying time with analysts, FSIs have privately expressed increased concerns about capturing scale from massive digital transformation initiatives. Many are running well past their original timelines and budgets, and the rapidly rising costs of cloud services aren’t helping. As the saying goes, “One FSI's expense is another computing provider's revenue.”

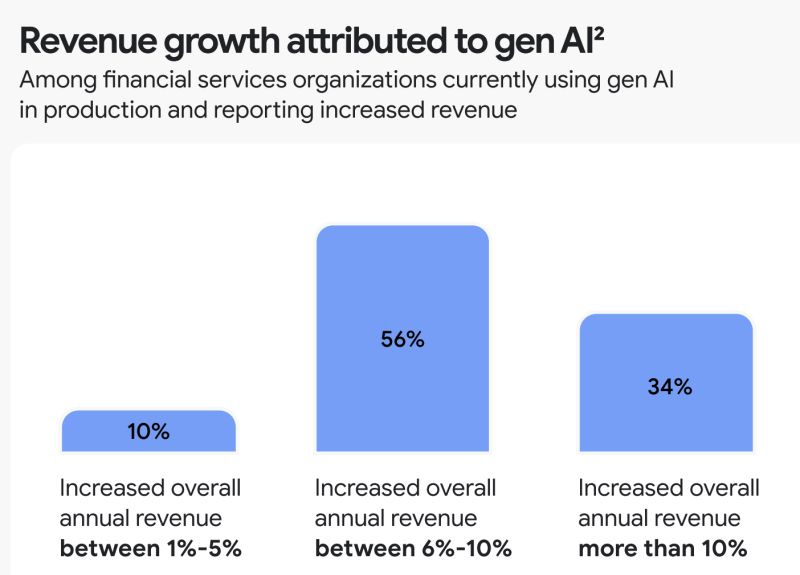

In response, and with 2025 planning underway, efforts are being made to apply more rigor to top GenAI use cases and eliminate the rest by year-end. On the surface, this seems feasible, as some initiatives have been in production for 6-12 months. Furthermore, recent surveys indicate that the majority of financial services firms expect not only significant productivity gains from GenAI but also close to a 10% increase in revenue or more:

With the latest analysis available, it’s becoming increasingly clear that long-term GenAI will represent a significant improvement over traditional machine learning pattern matching, despite its potential downsides, such as fabricated data, fragility, and deterioration. Another year won’t change this trade-off. And if your FSI would prefer to scale rather than simply cut costs, GenAI is a sufficiently discreet initiative to develop fintech-grade operating muscles.