The Overlooked Role of CFOs in the Digital Transformation of FSIs

Also in this issue: The Success of Revenue-Generating Digital Use Cases Boils Down to Two Metrics: LTV and CAC; Digital Channels: Overrated for Traditional FSIs?

The Overlooked Role of CFOs in the Digital Transformation of FSIs

Take a guess: which C-Suite executive in an FSI would make such public statements about technology spending?

“I just think like it's sort of mandatory, right? … Otherwise, we risk getting severely disrupted.”

“… even though all of the businesses in various ways are investing in technology and spending money on it, the drivers are actually pretty consistent across the entire firm even though it's really bottoms-up driven. And those drivers are consistent with what they've been: new products, features, and customer platforms as well as modernization.”

“…I think is interesting, that to the point about the driver being growth writ large, one of the things that we see is higher volume-related technology expense throughout the company.”

Which executive role is likely to feel that technology spending is mandatory, required in all parts of the company, and correlates with revenue growth? You probably guessed that it is a Chief Information Officer or Chief Data & Analytics Officer. They tend to fight for bigger budgets, enjoy building cool things, and view business lines and functions as similar. It is less likely, but you might have thought that this could be a particularly visionary CEO or Head of Strategy who imagined working for a technology company.

There might be other responses, but nobody would guess that this was a CFO. JPMorgan’s CFO, Jeremy Barnum, shared those perspectives during the recent analyst calls. Gone are the days of nitpicking CFO stereotypes. It sounds like modern CFOs act more like cheerleaders. What role, if any, is the CFO supposed to play in the digital transformation of an FSI?

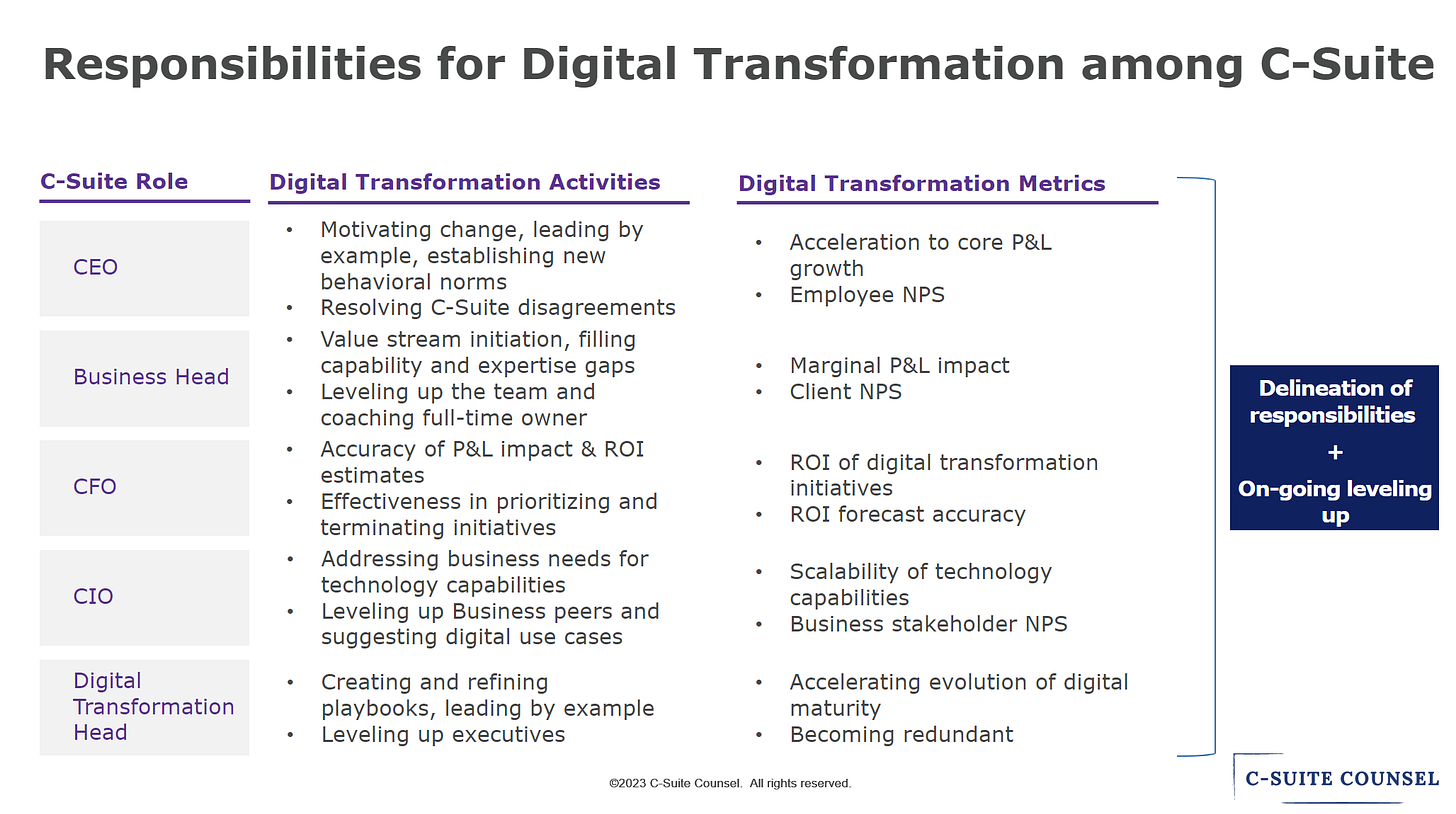

CFOs serve as the last line of defense. As the majority of digital transformation initiatives fail to generate a material P&L impact or break even, it falls upon the CFO to pose uncomfortable questions during prioritization and implementation. The CFO should be evaluated based on the ROI of digital transformation investments and the accuracy of predictions by business line and functional executives regarding those outcomes.

If JPMorgan's CFO understood that responsibility, he could have modified his pronouncements:

"The risks of disruption have been consistently overhyped, so we are rigorously evaluating every digital initiative for its ROI."

"Every business line and function has fundamentally different digital needs and current maturity, so we are prioritizing the few where ROI on technology spend will be the most significant and evident."

"There should be no correlation between revenue and technology spend across our company. Every IT initiative should result in higher platform scalability and internal NPS."

In my experience with CFOs, only a small portion think this way because they lack the operating muscles to perform these calculations and level up their peers. Instead, they often stick with their comfort zone of financial reporting and act as hands-off digital transformation cheerleaders. Here is how JPMorgan’s CFO views opportunities with generative AI:

“There's clearly some very significant opportunities, not for nothing, starting with technology developers themselves in terms of the opportunity for significantly increased productivity there".

For a CFO who understands the nuances of digital transformation, the "productivity" rationale should be a major red flag, not the highlight. More productive developers could be creating many features that the business group won't be able to absorb or that customers won't use or pay for. Instead, a good test for such rationale is to ask the Head of Engineering if the ten percent staff reduction could support the same business requirements due to the use of generative AI. In the great majority of cases, the answer would be "no" or "don't know."

In the next C-Suite meeting, ask the CFO how they understand their role in the context of digital transformation, and afterward, offer to help with leveling them up. Some don't know how to start, yet they would like to try new things because life is short.

The Success of Revenue-Generating Digital Use Cases Boils Down to Two Metrics: LTV and CAC

It has been fascinating to watch a discussion among banking and fintech experts about HSBC's launch of Zing. Zing is a cross-border money transfer app with some banking features aiming to attract younger customers from Revolut and Wise. Another newsletter discussed why this venture is designed to fail, but the experts are still having heated debates about the app features or the ease of customer onboarding, comparing those to Revolut and Wise. However, almost everyone is missing a much more fundamental question: Does Zing have a sustainable business model?

A business model clarifies whether the customer's long-term profit contribution is high enough, and that the customer’s acquisition is cheap enough to create a sustainable business, commonly described as LTV/CAC (long-term customer value divided by customer acquisition cost). For example, in the case of Wise, it generates $30-40 of revenue from the customer per quarter or around $150 annually. Assuming a 10% contribution margin, it translates to $15 per customer annually.

Compare that amount with Wise’s main acquisition channel, the digital referral program, which pays almost $40 for each referral on top of a free first transfer:

Since Wise tends to have a loyal fan base and not all word-of-mouth is paid, its LTV/CAC is probably still 2-3X. However, this referral amount is twice as high as it was a few years ago. Moreover, this relatively low-cost acquisition runway is ending anyway, with growth in consumer transfer volume declining to less than 20%. Wise is about to decide if it wants to avoid stagnation by boosting incentives for new customers even further.

What does this calculation mean for Zing? Since it doesn't have an early mover advantage like Wise and Revolut, Zing is facing a much harsher reality that banking and fintech experts are not discussing. Its acquisition cost would be much higher than Wise because it would be persuading customers of their beloved brand to switch to an unknown company with a sketchy-sounding name. This means Zing is a fine idea for HSBC's PR, but it would have to burn too much of its marketing budget to reach levels that matter to a $70 billion revenue FSI.

In contemporary times, achieving word-of-mouth virality solely based on product features is exceptionally uncommon. Ramp was already profiled in our newsletter as one of the most effective newer fintechs, last reporting growing 4X with 15,000 customers. Its value proposition lies in being an accessory to a business bank account by focusing on the billing and expense management process. Here is how Ramp’s Sales Manager described their differentiation in trying to get my business:

“With a Ramp card, all you have to do is swipe and snap a picture of the receipt, and the transaction data will automatically populate in our platform and match the receipt with no extra effort from your team. Then, it will sync and code the information on your accounting system to help make this system even more accessible. And the best part is that this level of automation and efficiency comes at no cost to you + we offer a 1.5% cashback.”

My business bank, like many others, already has a cashback card, and integrated receipt matching has been around for a while. Ramp's value proposition could work for some business owners whose banks don't have those features, so Ramp could probably grow from 15K to 100K customers over the next couple of years.

However, the 4X growth will start decelerating, as with other great fintechs, and Ramp would have to offer significant incentives to entice customers like me who are content with their current provider. Only then it would be clear if this fintech has a sustainable business model.

Traditional FSIs should apply the same logic when evaluating their next use case for digital growth. They need to consider what LTV and CAC they are expecting at scale and what evidence they have to back up those assumptions.

Digital Channels: Overrated for Traditional FSIs?

"... the fourth quarter was clearly very disappointing," Citi CEO Jane Fraser recently told analysts. How could the FSI which spends a larger portion of revenue than its competitors on technology produce such a surprising outcome?

Because the ROI from technology initiatives remains mixed, and their P&L impact is often negative. This is especially the case for B2B divisions like Citi's Fixed-Income Trading:

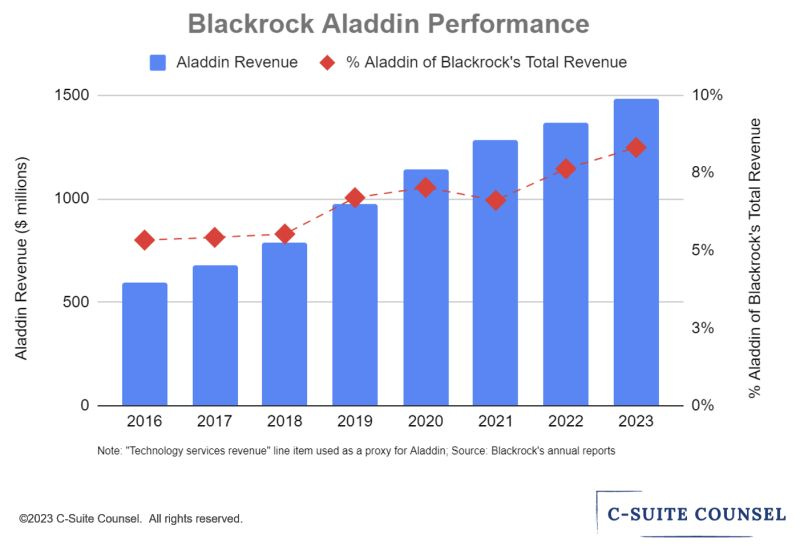

Even the best B2B FSIs continue relying on traditional sales channels. With 2023 results in for BlackRock, the monetization of its internal Aladdin platform remains one of the few success stories globally among FSIs and fintechs. As described in another newsletter, the integration of several superior differentiators across its business, operational, and technological models, in contrast to client in-house solutions and vendor offerings, explains Aladdin's unparalleled success. And yet, there's no 'rapid scaling,' with a 14% CAGR and the share of total revenue increasing by 3% in the last 7 years:

As traditional FSIs consider revenue-generating use cases as part of digital transformation, they should also remember that the more mature the target market, the more expensive it would be to acquire new customers at scale via digital channels. This is true even for the market leaders. Chase is paying $750 for new business accounts and up to $900 for new consumer ones:

If you think, with such heavy promotion, that Chase is emphasizing digital channels over traditional ones, you would be wrong. In a recent earnings call with analysts, "branch strategy and the associated staff for that" was called out as the first key driver. Moreover, Chase confirmed that in 2023, "we built 166 new branches, and we're planning about a similar number this year."

Other large banks are facing the same predicament. Bank of America is cutting 1-2% of branches annually in line with the banking trend in the US. Is this done because digital channels are more effective and growing in importance? No, the percentage of consumer sales through digital channels has stalled under 50%. Wells Fargo cut 6% of branches in the last 12 months. Is it because digital channels are sufficient for growing revenue? No, Wells Fargo’s revenue has grown less than 1% in the same period, far behind its peers:

Digital channels are stagnating across financial and insurance products, even in the most unexpected areas. Common wisdom states that money transfers are, of course, quickly moving to digital. Maybe domestically, but cross-border money transfers had some accelerated shift around Covid and then have stalled for more than 3 years:

As clients become increasingly content with highly evolved products, the efficacy of digital outreach will keep declining. Even Revolut’s CEO recently recognized that “Physical presence is one of the elements that helps establish a bank’s reputation and trust with customers.” FSI executives should disregard the hype around digital channels and continue investing in traditional acquisition experiences.