“Show Me the Money”: The Only Response to Digital Transformation in FSIs

Also in this issue: Leveraging Proprietary Data Is the Ultimate Moat for Traditional FSIs

“Show Me the Money”: The Only Response to Digital Transformation in FSIs

When Gordon Gekko famously declares in Wall Street that “Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit,” he’s making a point that has held for millennia: money makes the world go round. Even in politics—where pontification is an art form—money drives decisions.

Digital transformation in FSIs is no different. Executives can drown the room in buzzwords about digital innovation, but unless they can answer the ultimate question—" Show me the money”—it wastes shareholders’ time. That’s why the hardest part of digital transformation isn’t the “digital”—it’s the “transformation.”

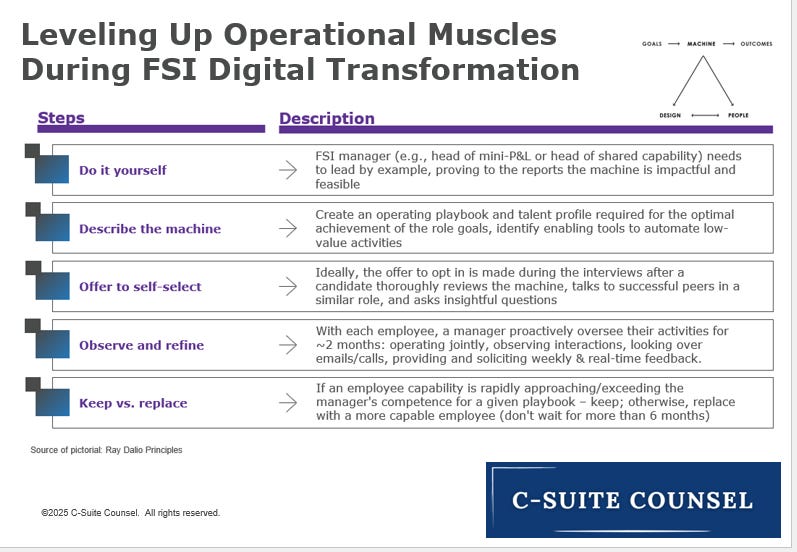

Launching digital products, coding new features, and adopting flashy tech are all things FSIs could accomplish just fine within their 20th-century silos. The real challenge—the painful, unavoidable one—is leveling up operational muscles to maximize the ROI of digital initiatives.

Jamie Dimon’s recent town hall remark that Bank of America is better and ahead of JPMorgan Chase in digital illustrates a misplaced focus on superficial transformation. JPMC employees initially thought he was joking. The only profit-related digital metric in which BofA appears “ahead” is tech spending as a percentage of revenue—12% vs. JPMC’s 10%.

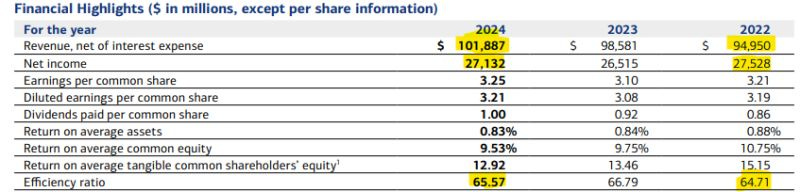

Maybe Dimon was impressed by BofA’s habit of including multiple digital engagement slides in every quarterly earnings presentation. But regarding true digital transformation north star metrics, over the past two years, JPMC’s revenue has grown 40% and net income has surged 60%. In the same period, BofA’s revenue has barely moved, while its net income and efficiency ratio have worsened:

Such misplaced focus on “digital” components is widespread among FSI executives, most of whom fail to grasp or forget what true transformation entails. When confronted by transformation-ready peers, these traditional executives struggle to understand why they should abandon familiar, functional systems in favor of a riskier, more complex paradigm.

In my experience, when challenged to elevate their operational capabilities, their typical reactions include:

You're downplaying the importance of my function.

You don’t value my input.

You think you know more than me.

Now, imagine you’re among the small percentage of executives in a traditional FSI who truly understand what meaningful transformation looks like—someone who sees continuous improvement as a daily routine. How do you think the rest of the organization would respond to your push for change?

To be fair to traditional FSIs, transformation-ready executives are a minority in many fintechs as well—just a slightly larger one, around 20-30% instead of 10-20%. I recently asked the Chief Product Officer of a $100 million B2B fintech in the US whether tariffs had impacted their product strategy. “My team immediately revised product roadmaps and updated positioning pitches, but sales and marketing heads weren’t interested.”

Without “show me the money” as the primary goal, digital transformation becomes overkill. Take the current trend of insourcing IT talent. Over the past three decades, large U.S. FSIs have come full circle—offshoring, outsourcing, relocating south, doubling down on outsourcing and offshoring, then insourcing to lower-cost domestic locations, and now bringing talent back to expensive hubs near business teams. This shift is a necessary digital transformation step from an IT product model to value streams and platform maturity. It also aligns with the need for newly formed units to collaborate in person 2-3 days per week.

However, the key to successful insourcing to HQ hubs is a highly selective approach that accelerates business value capture in priority areas. In practice, some traditional FSIs apply this strategy across the board, often prioritizing improvements in back-office capabilities instead of front-end value creation. Even worse, some rely on reacting to regulatory pressures—like data governance and deficient controls—as the foundation for digital transformation. This only adds complexity, drives away top talent, and ultimately leads back to 20th-century waterfall models with rigid silos that were already sufficient for those tasks.

A digital transformation executive at another large US bank recently described their culture as “policy-centric,” driven more by avoiding bad regulatory outcomes than by enabling upstream groups to generate more revenue. As a result, very few of the so-called product teams in enabling functions could articulate why they were building specific capabilities. “We could easily cut 30-40% across the board, and transformation would accelerate without negatively impacting business outcomes.”

So what should the 10-20% of executives who genuinely understand digital transformation do? Sisyphus was condemned by Zeus to endlessly push a massive rock up a hill, only for it to come crashing down each time he neared the top. You need to recognize if your CEO is playing a similar role. Do they justify digital transformation through compliance and risk factors, or do they regularly demand from their reports, “Show me the money”? If it’s the former, it may be time to move to a more advanced FSI or a fintech where transformation leads to value creation.

Leveraging Proprietary Data Is the Ultimate Moat for Traditional FSIs

A couple of years ago, many FSI and fintech CEOs bewilderingly bought into the notion that LLMs could replace structured data and predefined use cases. Influenced by experts, they were convinced that these models could sift through informational garbage to uncover profit-generating insights. The initial excitement has since waned, only to briefly resurface with the latest hype around AI agents: "Our data isn't structured enough for Machine Learning, but what if we leapfrog directly to Agentic AI?"

Leading fintechs didn’t indulge in similar illusions; they understood that structured proprietary data is the ultimate moat, recognizing that they start at a disadvantage compared to incumbents. When Nubank, Revolut, or Klarna build core applications in-house—replacing hundreds of SaaS tools and plugins—it’s clearly to preserve and maximize the value of proprietary data.

The real challenge, however, even for these disruptors, is breaking down internal data silos while enabling the rapid deployment of use cases, including with GenAI tools. Klarna’s CEO recently highlighted their use of graph databases to address this issue, opting for a more sustainable solution rather than continually patching together an array of SaaS providers:

“… all forms of knowledge of what Klarna is and what it has learnt was fragmented over these SaaS—most of them having their own ideas and concepts and creating an unnavigable web of knowledge that required a tremendous amount of Klarna specific expertise to operate and utilize… The side consequence of this was the liquidation of SaaS—not all of them, but a lot of them. And not for the license fees, even though those savings have been nice, but for the unification and standardisation of our knowledge and data.”

Klarna’s three million daily transactions and other business processes generate a substantial volume of proprietary data, now structured enough to drive meaningful impact with LLMs. In its recent IPO filing, Klarna outlined the following GenAI vs. ML use cases at scale:

GenAI

Higher purchase conversion: Personalized shopping feeds

Lower customer support costs, time, and errors: Chatbots

Higher engineer productivity: Code creation and review

ML

Higher conversion rates and lower losses: Credit underwriting

In contrast, traditional FSIs are still lagging in adopting this data-driven mindset. Despite close to $20B in technology spending, LLM suite access for 150K employees, 60K employees in tech, and 3K in data-related functions, JPMC—like it did decades ago—still sends out a monthly campaign to every resident in a region, increasing the bonus offer by $100 for no response. With the CEO’s intense focus on full-time in-office work, does he believe this will be the catalyst to end the kitchen-sink approach?

To be fair to traditional FSIs like Chase, those programs are still likely profitable overall, but they don’t have the same intensity to maximize ROI as leading fintechs. The fundamental contrast lies in the disregard for data-driven prioritization of investments in quasi-government financial institutions. The Trump administration recently shut down a chain of community development financial institution (CDFI) funds across predominantly low-income states. Guess how Mississippi, the state that received the most funding, defined the results of this program’s impact? Naturally, by how much money it gave away:

The amusing crossover between government giveaways and fintechs’ zeal to maximize the use of proprietary data is seen in the so-called “mission-driven” segment. The ones who genuinely believe in their mission tend to fail, while other fintechs employ a sleight of hand when measuring impact.

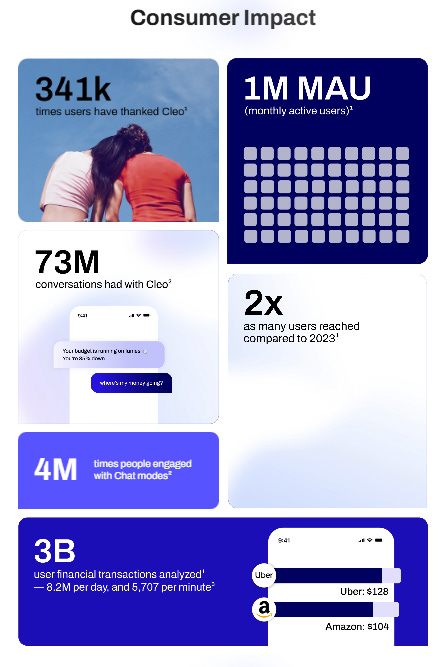

Cleo, a personal finance app with one million monthly active users and $185 million in annual recurring revenue, appears to be a success story in nudging consumers toward its mission of empowering financial wellbeing. However, a closer look at its proclaimed customer impact metrics reveals a different reality—there’s no measurable improvement in financial well-being, just a focus on tracking engagement:

In fact, given the average subscription cost, a significant portion of paying customers may not even be actively using the app—making it resemble more of a gym membership business model. This is probably not some Machiavellian manipulation; rather, it’s a subconscious bias toward measuring what’s easy while avoiding inconvenient truths, like the lack of meaningful financial wellness impact beyond self-reporting.

Customers appreciate Cleo for its “roasting” mode, where the chatbot gives them a hard time about spending. But has this “AI-driven” fintech developed a unique way of using data to curb excessive splurging? The most notable "AI-powered" example involves a customer manually entering a merchant name and defining how much to save after each transaction with that merchant:

Proprietary data differentiation is especially crucial for risk-based financial and insurance products in developed markets. Two main surprises for startups competing with incumbents in these products are: 1) their inability to catch adverse selection due to insufficient data, and 2) even the world’s best UX loses to a proprietary data set every time.

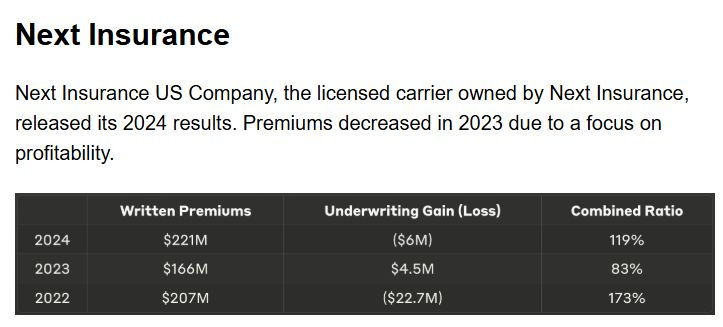

Eight years after its launch, Next Insurance has barely grown since 2022 and posted losses again. When the founders of Next Insurance sold their bill payment app, Check, to Intuit for $360 million in 2014, it wasn’t unreasonable to prioritize small business insurance as the next opportunity. However, like other insurtechs, the Check founders underestimated the importance of proprietary data for risk-based products.

I got a personal window into how the lack of data leads to bad decisions despite having great UX. With no claims or other engagement, Next Insurance hiked my renewal price by 66%, citing climate change and inflation (LOL). So, I switched to a great offer from an incumbent. Without massive proprietary data, relying on UX differentiation is like depending on AI tools. This is why leading "AI-native" fintechs and insurtechs founded in the last decade are seeing their stock prices down 75-95% from their all-time highs.

Of course, traditional FSIs need to be very careful when discussing the beneficial use of data. State Farm recently fired an executive who was secretly recorded on a Tinder date explaining why the carrier exodus from California would continue based on the disconnect between pricing and risk data. Coincidentally, the company notified regulators simultaneously that it would stop writing new policies in the state.