What Type of Business Executive Could Drive Digital Transformation in FSI?

Also In This Issue: From the Driver's Seat - Insights of the Former Head of Retail & SME at Raiffeisen Russia, Other FSI Digital Transformation Weekly Reads

What Type of Business Executive Could Drive Digital Transformation in FSI?

In one of the newsletters, we highlighted the necessity for a business executive to lead digital transformation, not IT/Data leaders. Some LOB heads may not care for it, and if the CEO agrees, there is no need to keep challenging them. Our newsletter strongly advocates for quality over quantity, proving with consistent evidence that it is more effective to do less digital transformation but do it well. Every year or so the peers of such reluctant LOB heads are welcome to suggest a potential digital use case and jointly level up operating muscles, but, otherwise, such business executives should be left alone.

However, some LOB heads are enthusiastic about accelerating digital transformation in their FSIs. In my meeting with the LOB President of a top-10 P&C carrier and his reports, he expressed eagerness to launch an AI pilot and even agreed to station a cross-functional team beside his office, promising to visit and support them daily. He concluded the meeting by saying, "Please finalize details with Yakov and let's communicate our plan to the team members on Monday." Leaving the conference room, I overheard two of his reports speaking in a hallway, "He won't remember this by Monday…” They turned out to be correct.

Such an inspirational-but-hands-off attitude is prevalent among business leaders in FSIs. While it is fun to discuss digital transformation in conferences, interviews, and LinkedIn posts, it takes a different level of commitment to drive it personally. A typical FSI business executive thinks about digital transformation like a sports club owner - they provide support and funding to the team and hire coaching staff, but don’t involve themselves in the team's composition, game strategy, and especially in training players. The good news in my experience is that nearly all FSIs have one or two business executives who are willing to roll up their sleeves.

In one such FSI, I was in a meeting with the new CEO and leadership team of a mid-size life insurance firm who were eager to embark on a digital transformation. They quickly prioritized two groundbreaking use cases, agreed on the readiness checklist, and two LOB heads raised their hands to own each value stream. However, given my past experiences, I assumed that most of their commitments would be forgotten by the time I returned a week later.

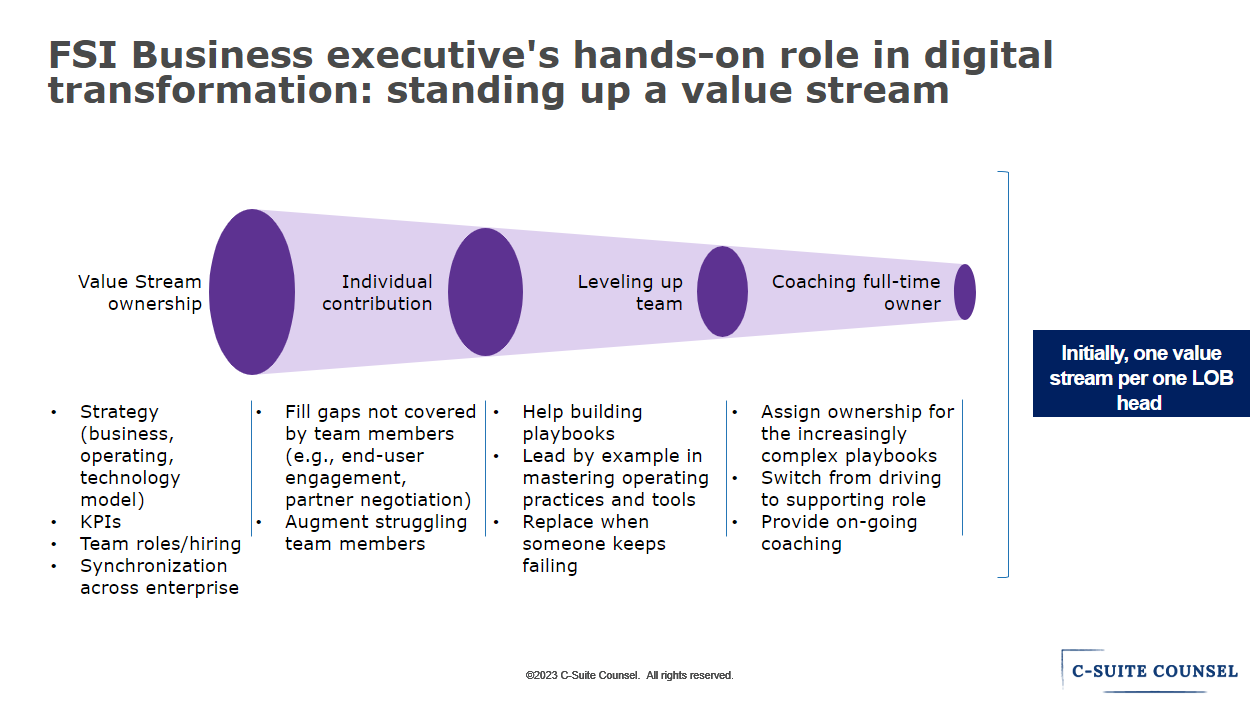

To my continued astonishment in the upcoming months, the outcome was much better. Within three months, a company previously struggling with foundational IT capabilities had two value streams operating like a decent insurtech. Such was the impressive power of two driven business executives who took ownership of developing new operating muscles for themselves and their teams.

They were excited to learn everything, from Agile routines to DevOps tools. They jumped into the tasks no matter how small they were, all to ensure that the team was making progress. Their enthusiasm was infectious, inspiring their teams who, like me, could not have imagined that such two heavy hitters would work with us in the trenches. They also invested a lot of time into bringing along Enterprise heads who were concerned about losing authority (read this newsletter for relevant playbooks and insights).

After a few weeks of observing their behavior, I became very curious as to what made these two business executives so different and why they would personally get involved in the work while most of their peers would delegate and hope for the best. While significant incentives for hitting aggressive revenue targets were a factor, they weren't the only reason. Many FSI business executives are already millionaires while continue earning comfortable salaries, so money by itself couldn't be the decisive factor for such unusual behavior. When they finally shared their backgrounds, my puzzlement was no more. Their life circumstances shaped them into self-starters.

One of the executives grew up in an entrepreneurial family, where his father and older brother built an insurance brokerage from scratch. He worked there from a young age and also held leadership positions with a local nonprofit, including overseas assignments. The other executive became a single mother at a young age and had to forego college to begin working full-time. Without a professional network or formal credentials to lean on, she felt compelled to excel in every work assignment and outcompete peers with a traditional background.

If you are an FSI business executive reading this newsletter, chances are you weren’t a self-starter to begin with. You likely entered a financial service or insurance company after attending a well-known college and completing a traditional internship. For the past 20-30 years, you have been climbing the ranks, trying not to disrupt the status quo too much. At this point in your career, the idea of taking on hands-on activities by yourself doesn’t seem appealing to you, especially since you are surrounded by VPs who are expected to handle such tasks under your mentorship. I sympathize with your strong preference for the status quo from the opposite end of the spectrum. As someone who founded/co-founded five companies starting while still in college, I could never quite fit into Western corporations, and no amount of coaching was able to change that. Most of us like who we become and don’t care to transform how we operate.

Except, there is one paramount downside of hands-off LOB heads who are trying to champion digital transformation in their FSI. Hundreds of people in their group are destined to waste years of their professional lives and millions of the company's budget by learning how NOT to approach digital transformation. Although such LOB heads could transition to a role where digital transformation is unnecessary or even retire, hopefully, this newsletter inspires them to roll up their sleeves.

From the Driver's Seat: Insights of the Former Head of Retail & SME at Raiffeisen Russia

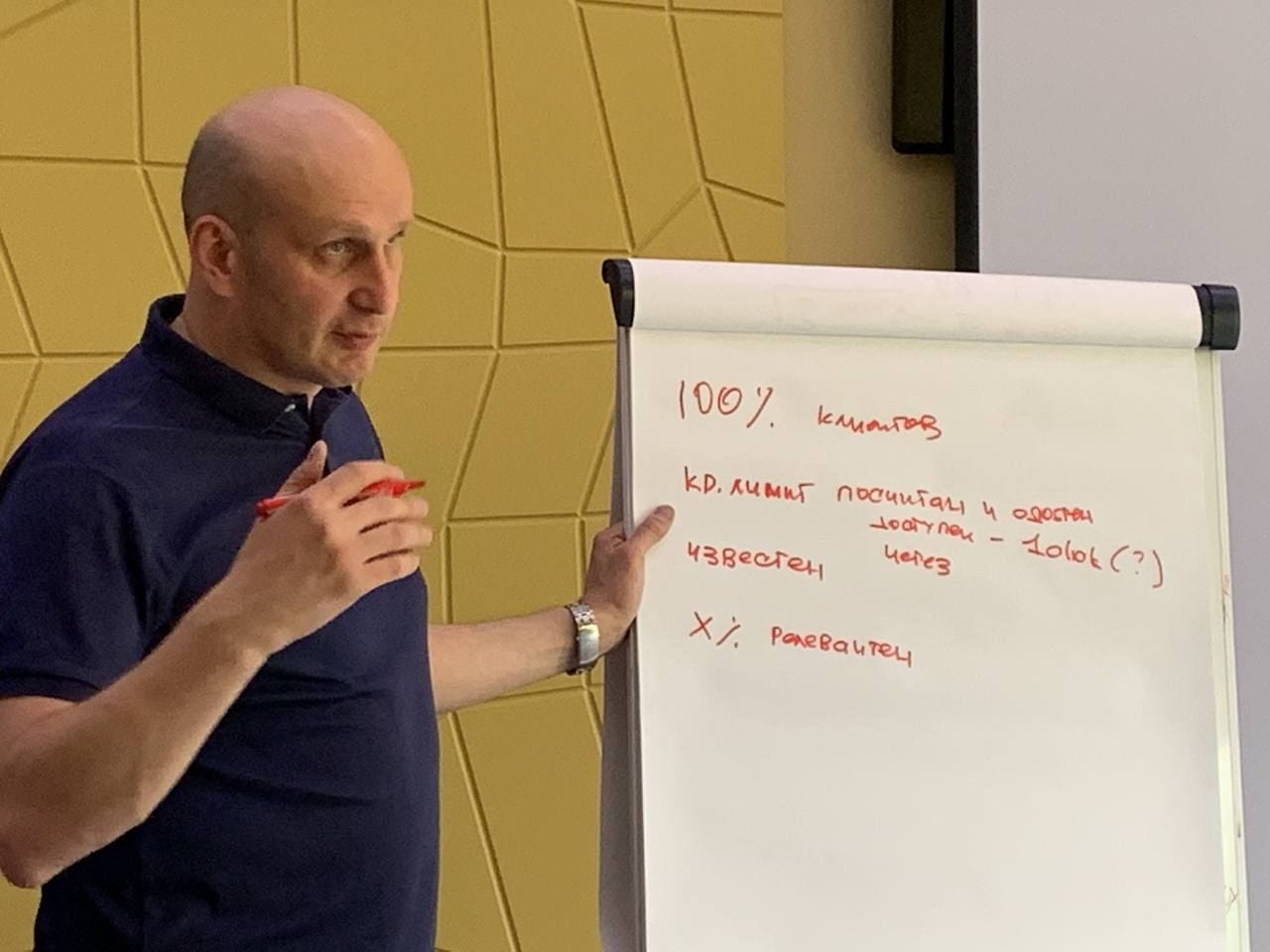

In 2018, Roman Zilber became the Head of Retail & SME at Raiffeisen Russia while the whole bank was in the midst of a digital transformation initiated by the CEO. He resigned from the bank in March 2022 and now lives in Israel consulting FSIs on digital transformation. Roman shared with FSI Digital Transformation Weekly what he learned from personally driving a massive digital change.

Initially, the need for transformation was not obvious since the bank was already running at a very healthy ROE and Cost-to-Income ratios. The shareholders were skeptical about both the fundamental change itself and its desired main outcome of making the bank the most recommended one in the country within five years.

"Our net interest margin was at least 1% higher than our competitors due to a lower cost of funds. Despite this advantage, we became concerned about the growing number of client complaints regarding the bank's digital features. If we didn't catch up with emerging digital-native competitors, the potential revenue loss would be significant. Plus, the initial investment required for digital transformation appeared minimal - mostly an organizational reform aimed at creating joint IT and business teams."

To reflect the digital transformation goal, the bank chose NPS as its North Star. The KPI was selected based on the DNA of the bank’s business model. The bank began in the late 1990s with the invitation-only channel and later evolved into a premium institution known for its high credit rating and exceptional customer service. This model allowed for higher prices, resulting in a superb ROE of 25%.

The CEO was eventually able to persuade stakeholders to agree on a much higher NPS and cross-functional operating model as the target state of the digital transformation. However, the Board requested that the bank maintain its ROE and Cost-to-Income ratios to ensure that the transformation would not become an innovation spending spree.

The bank faced its first major obstacle when the shift in the operating model began translating into personnel implications. The bank leadership believed it was essential to incentivize all employees toward the goal of achieving higher NPS, including the IT department, which had no direct influence on it. To facilitate this change, many IT specialists were transferred to the product and service teams. Despite the IT leadership's full support, several middle managers and senior developers disagreed with the move, resulting in some of them leaving the bank.

"Some of our IT colleagues wanted to maintain incentives for technology excellence, while we believed in the importance of setting common goals for both IT and business, with a focus on NPS and other business metrics. In hindsight, we could have made more of an effort to find a middle ground that involved scalability and internal NPS. However, measuring these factors was challenging, especially given the pace of our transformation, so we kept moving forward."

After establishing the KPIs and organizational structure for the target operating model, the next step was to hire hundreds of top-notch developers in order to build an in-house solution that would replace the undifferentiated vendor platforms. The bank's reputation aided in attracting qualified candidates, but the initial costs were significant. To comply with the Board's mandate for stable ROE, Roman made a bold decision to close 30% of the branches.

"The cuts were significant, including every branch in some smaller cities. Despite some internal protestations, I took a leap of faith that customers wouldn't mind which physical branch they were assigned to, as long as they received uninterrupted support anchored by superior digital features."

The bet paid off in spades: not only was there no client attrition, but the savings were substantial enough to cover the cost of IT hiring and to allow for overinvestment in marketing. The latter part proved crucial as it allowed the bank to maintain the semblance of availability despite having fewer branches on the main street. So the bank, which serviced 1.5 million customers with 180 branches before the start of digital transformation, ended up successfully serving 1.8 million with only 117.

At the same time, Roman began to recognize the first of many personal limitations in his operating muscles: reluctance to share power with the front lines.

"I found myself in seemingly ineffective interactions with the newly established product teams. Although they were all top-notch, we weren't working together seamlessly. As someone who considers myself intelligent, I had many thoughts and suggestions on what the product teams were doing. However, some dismissed my suggestions while others accepted them as orders, both outcomes frustrating me. Then one night, a realization hit me: digital transformation doesn't create new decision-making power; rather, it redistributes power from executives to the front lines. Empowering your people means disempowering yourself!"

To develop new operating muscles, Roman divided his target responsibilities into four categories: organizational structure and KPI setting, executive team hiring and development, strategy, and alignment with the Board. He also informed the product teams that they had operational decision-making authority going forward and could use client feedback to prioritize backlog in any way that they believed would improve NPS.

Over the next six months, Roman intentionally created a focused agenda before each interaction to prevent the return to old operating habits. In addition, he introduced a demo-day cadence where the product teams are being challenged not by top management but by customer-facing counterparts. During these sessions, the teams actively debated the scope and approach with their peers, while Roman emphasized the importance of using a common language.

The first year of the operating change was challenging for everyone involved. Several IT leaders departed and Roman replaced half of his leadership team with stronger hires. However, by the second year, the digital transformation had become much smoother, resulting in fewer daily distractions and allowing Roman some breathing room to refine everyone's KPIs.

"While we were unsure what it would take to achieve a highly-recommended-bank position, insights from the NPS research convinced us that "instant" service was an absolute necessity to reach this goal. We engaged in a lengthy internal debate over the definition of "instant." Some argued that reducing response time from hours to 15 minutes was sufficient, while others, including myself, believed that we needed to aim for milliseconds, which would require a complete overhaul of our product, operating model, and technology.

From that experience, I learned to set more ambitious short-term goals for the product teams, which unlocked their creativity and encouraged strategic thinking about how to transform the business."

Digital transformation presented numerous challenges for Roman, like a giant mountain with an elusive peak. However, overcoming each challenge gave the bank a competitive edge that left competitors farther behind. One of the final hurdles Roman faced before leaving the bank was shifting the scope of the product teams. To his surprise, the teams did not naturally consider the bigger picture and continued to make improvements even after a product was functioning satisfactorily.

"When the COVID lockdowns began, we had to revamp all the teams' backlogs. We believed it would be easy to mobilize our most capable teams to work on the new products, but many of them were not pleased, insisting on finishing their 1-3-year backlogs first.

I realized that there was a mindset difference between a banker, who would readily switch to something new, and IT professionals who get attached to their current build. They might even risk missing their KPIs to see it through. This taught me to engage more intensively with product leads and help them think more strategically as business owners."

In the end, the outcomes of the digital transformation exceeded the Board's expectations. The bank was not only able to preempt any client loss, but the high NPS also resulted in a low-cost referral channel: new profitable client growth increased from stagnant to 20% YoY.

“NPS became better almost right away, and kept improving 5% annually, expanding the gap from competitors. As we initially suspected, NPS was strongly correlated with the strength of digital features, so we focused on web, mobile, and then chat to expand our NPS lead.”

I hope this first-hand account inspires more FSI Business executives to get into the driver’s seat. You could follow Roman directly on his LinkedIn page for more. For additional insights on the engagement between LOB heads and IT leadership, check out this newsletter.

Thank you.

So would these LoB leaders have Sr Operations titles in Insurance companies or President of the particular business groups? I guess I’m wondering where is that line for calling too high when selling Digital transformation consulting and who is actually motivated like you described to actually deliver something vs just thinking about it and getting a nice binder from McKinsey et al