Should FSIs Give Up on Improving Their Random Digital Cross-Sell Efforts?

Also in this issue: It's OK for FSIs to Use Smoke & Mirrors to Jump-Start Transformation; Monetizing Excess and Victimhood in the Age of Decadence

Should FSIs Give Up on Improving Their Random Digital Cross-Sell Efforts?

When it comes to the five digital pillars of the 21st century—Agile, AI, API, Cloud, and DevOps—Capital One is second to none worldwide among traditional FSIs. Well, maybe not the whole Capital One, but at least its credit card division. Would you like your FSIs to be as capable as Capital One at cross-selling to your existing clients? Here’s their secret: rotate the same random offers to their customers and hope for the best.

Here are their recent offers to me:

“Earn 4.25% APY, one of America's best savings rates”

“ Pre-qualify to see your real rate on millions of cars.”

“Save 50% of any handcrafted bev at your local Capital One Cafe.”

That “best” savings rate is almost a full percent below the actual best on the market, I don’t own a car, the nearest Capital One Cafe is a 20-minute drive away, and why would I go to a bank for coffee in the first place? When the first bank in history, the Bank of Babylon, was cross-selling to its customers four millennia ago, it was missing a smartphone app, but the process was probably quite similar.

What about Bank of America with Merrill and their knowledge of years of my transaction data? BofA spent $12 billion on technology last year, but when it comes to cross-selling, it is similarly ancient, asking clients to pick from random rotations of standard offers:

Akin to "Nigerian princes," the world’s leading FSIs push random offers to their long-term customers, satisfied with a minuscule uptake rate. Despite proclamations of customer centricity, what is behind such a lack of progress? This is especially confusing given a decade of scaling AI. Generative AI alone, according to a recent McKinsey survey, constitutes up to 20% of digital budgets across FSIs, roughly translating to $50 billion annually in worldwide spending:

The reason is the analytical complexity of programmatically analyzing millions of customers to develop personalized offers. We might be in awe of micro-pricing by Delta Airlines for airplane seats or Progressive Insurance for auto coverage, but even those firms don’t analyze a person’s specific transaction history to offer a custom price.

And GenAI? Since the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022, executives in financial services and insurance companies have hoped for an analytics engine that could synthesize transaction history, replacing the manual effort that would be required and is not economical at scale. While we are no longer hearing about AI catastrophes for humanity, the forewarnings about GenAI's ability to perform analytical tasks are still prevalent:

To prove the feasibility, about a year ago, a startup called Parcha raised $5 million in a seed round to implement a human-like agent at scale using Generative AI:

“What makes an AI Agent unique compared to a more traditional workflow automation tool is their ability to autonomously carry out a task while dynamically react to the information it learns at every step, much like a human does. What makes Parcha’s AI Agents especially powerful is that they can learn to carry out these tasks using the same policies, procedures and tools that are already used by humans.”

After spending a year with banks and fintechs across the full spectrum of compliance-related use cases, Parcha recently published its lessons learned. GenAI agents can't replace FSI employees with complex roles since hallucination-induced errors would multiply across integrated tasks. However, GenAI can enable those employees to reduce data search and cleansing time with standalone microservices.

Until some undiscovered technology can analyze full client engagement history at scale, FSIs will continue their kitchen-sink approach to cross-selling. The only recent innovation from leading players like Chase and PayPal is to step up the monetization of customer transaction data for external cross-selling. Since nobody seem to know how to use that data internally, FSIs might as well sell it to the highest bidder.

If there is room for marginal investment, it might be to ask clients what products they would like and pay them for a thoughtful answer. Or would that be too customer-centric?

It's OK for FSIs to Use Smoke & Mirrors to Jump-Start Transformation

We often discuss how, with digital transformation, FSI executives prefer the "digital" part because it's fun to buy stuff and form partnerships but not the "transformation" part because it disrupts their routines. Since a typical FSI CEO is not a dictator, they usually try to get their executives moving with transformation using either consultants (e.g., “McKinsey told us”) or external forces.

Generative AI has been a convenient rallying cry for the former. At a recent conference, Chubb’s CEO Evan Greenberg explained:

… cycle times of change are currently very long for insurers—typically two or three years. “In my company, our cycle time of change is roughly a year, and we’re trying to lower that now to weeks. We have areas that are down to months,” he said.

“It’s AI and the tools of that, and other technologies and the insights, and how you organize and the skill sets you use” that are important contributors to lower cycle times of change, he suggested.

“It’s no longer underwriting. It’s underwriting and engineering, and how you put all that together with AI.”

Notice that the operating model message (organizing, skills, cross-functionality) is nested in the overall aura of AI. It's not like some companies couldn't do daily releases for two decades and some FSIs for a decade, right? However, if GenAI is the final impetus for your FSI to collapse business and IT silos into cross-functional teams to increase velocity, fine—whatever breaks internal politics.

US Bank is learning what happens without a change in the operating model the hard way. After investing $8B in technology since 2019, the country’s fifth-largest bank is only now starting to see a payoff, while its stock is 20% behind the Regional Banking index over the same period:

The reason for such delay in returns is explained in US Bank’s own presentation. Its digital strategy focuses on 20th-century efficiencies rather than transforming operating and business models. Digital transformation is too complex and risky to be used solely to cut costs; it is an overkill. Not surprisingly, US Bank has been measuring success by vanity KPIs rather than accelerating revenue growth and scalability, the north stars of digital transformation:

For FSIs using Generative AI as the raison d'etre to jump-start digital transformation, the trick is to initiate that novel operating model construct with a more basic analytics engine but not publicize that widely. The teams will crash and burn if starting with GenAI, and the digital transformation will get a bad reputation in the organization for years.

Monetizing Excess and Victimhood in the Age of Decadence

Being an FSI in the Age of Decadence is a double-edged sword: while there are few real pain points left in financial services and insurance, consumers and businesses have tons of excess cash they would like to spend. Consumers spend a trillion dollars annually on each of the alcohol, tobacco, and junk food industries globally, so how can FSIs get their clients to be as excited to spend more money on their products?

Luckily, the current zeitgeist has prescribed for everyone to feel like a victim, creating a unique environment aptly described by Louis CK fifteen years ago as "when everything is amazing right now and nobody’s happy." This means FSIs could monetize imaginary problems with imaginary solutions.

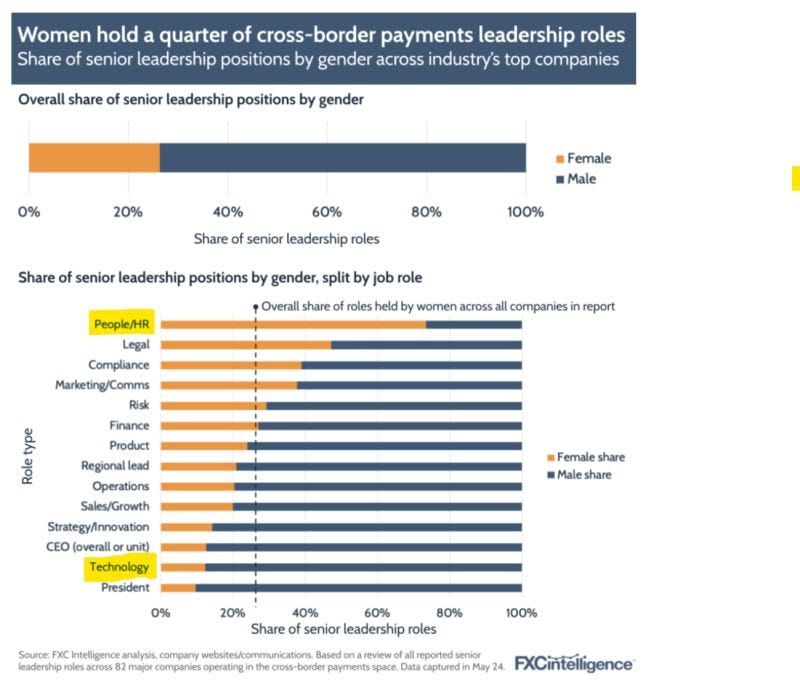

The set of “victims” is large enough to provide plenty of targeting opportunities. Even millionaires could be victims. For example, if your identity group has a smaller representation in some leadership roles in FSIs, congratulations—you could feel like a victim. And nobody will care if you are overrepresented in other roles.

If one identity group has less money than another, they are considered “victims”. Sure, any reporting on disparity typically ignores that: 1) in-group disparity is magnitude higher than across groups, 2) six decades of massive government and FSI efforts have only exacerbated disparity, and 3) no successful fintech exists that has effectively addressed these issues. Nevertheless, these pesky considerations are reliably ignored, perpetuating a sense of sadness about each group's plight:

Of course, nobody has been a victim for longer than young people. First, Millennials and now Gen Zers in the West have been suffering from supposedly unmet financial and insurance needs, as if villagers from Mongolia to Burundi might be losing sleep over it. The latest support came from Scott Galloway, a marketing professor at NYU Business School. After a small portion of kids from affluent families set up protest camps at some of the country's most elite universities, Scott expanded on that with "Young people have every reason to be enraged:”

Looking at the actual data, young people in the US are doing great financially - they are making more money than previous generations, making savvier financial and insurance decisions, and are poised to have the most prosperous retirement:

But the media will keep bombarding every identity group to forget about their reality and feel like victims. The question is, how should FSIs go about monetizing it? One fintech came up with a novel path.

A former teen model recently raised $2.8 million for an app that is supposed to address the social media-induced depression crisis among GenZ, caused by constant comparison to the material well-being of others. The solution? A social app with detailed comparisons of users' spending and salary, along with shopping incentives. And, of course, it is called FRich ("F@%ing Rich") to ensure users’ mental harmony.

Since the first rule of capitalism is to give people what they want, and younger people want to feel anxious, FRich creates more anxiety and then monetizes it via affiliate marketing. Acting in the people’s best interest would be the opposite - asking users to spend less time comparing themselves and spending less money to be like others. But that likely means less profit. Which path would the leading FSIs pursue?