Some FSIs and Fintechs Shun Customer Understanding: Does it Matter?

Also in this issue: Data Monetization's ROI Hinges on FSIs Managing Three Types of Risks

Some FSIs and Fintechs Shun Customer Understanding: Does it Matter?

What would FSI executives wish for if they possessed a magic wand? Perhaps fixing myriad issues in business, operating, or technology models? Or accelerating digital transformation to catch up with the maturity of leading peers and fintechs in their vertical? Maybe sorting through the untapped customer complaints to prioritize changes in products and channels? Instead, in a recent survey, the majority of FSI executives expressed a desire to know the future of their customer needs:

Why would FSI executives waste their magic wand on some esoteric distant data point? Because imagining the future is way more fun than fixing the present. This surprising response also implies that they already understand today’s needs of their target customer segments. But do they really, and does it matter?

Will Customers Be Excited When FSIs Build a Novel Solution?

Taylan Turan, Group Head of Customers, Products, and Strategy for HSBC’s Wealth and Personal Banking, recently underscored his commitment to "exceptional customer experience" through the new fintech subsidiary, Zing. In aiming to compete with fintech like Wise and Revolut, Taylan pinpointed three key customer needs:

Instead of focusing on the unmet needs of Wise and Revolut customers, HSBC has emphasized why its existing clientele prefers to remain loyal, particularly when the user experience mirrors that of fintech platforms. However, would this alone suffice for Zing to entice customers away from these fintechs? Certainly not, as these customers already favor their current product experience.

Conducting interviews with a statistically significant number of prospective consumers should be deemed a fundamental prerequisite before launching a company, especially when establishing a fintech subsidiary within a competitive landscape marked by prior failures and formidable competition from the world's leading fintechs. Yet, surprisingly, many FSI executives display limited interest in engaging in such hands-on activities.

HSBC could allocate $100 million towards Zing's marketing efforts and even lower prices to near-zero marginal profit. However, without a comprehensive understanding of customer needs, such an investment risks being futile.

A comparable oversight appears to be occurring within the realm of AI-based chatbots. Had FSI executives been attuned to customer needs, they would have observed a growing discontent with this support channel. Instead of relying solely on chatbots, customers are clamoring for more accessible, high-quality human support replicating the personalized experience of visiting a branch. Unironically, despite proclaiming their obsession with customer satisfaction, FSI executives persist in doubling down on AI-driven customer interaction strategies, as revealed in a recent survey:

Are Fintechs Always Superior in Understanding Customer Needs?

It is widely acknowledged that fintechs, as a collective entity, possess some inherent advantages over traditional FSIs, particularly in effectively understanding and addressing user pain points. As a reality check of this ethos, consider how the founder and CEO of Coinbase describes their top use case:

Digitizing the dollar. Despite high demand for the dollar in many regions around the world, many can't open USD bank accounts, until the adoption of dollar backed "stablecoins", which now exceeds $100 billion. A digital dollar, like USDC, is essential for our global competition with China, which began investing in a digital Yuan in 2019.

To distill the convoluted description, it appears that the most pressing customer need is the ability to open a USD account in regions with FX restrictions. Like HSBC, Coinbase outlines a solution it aims to provide rather than surveying consumers to ascertain what is lacking from their current providers. It's conceivable that some individuals might prioritize circumventing capital controls as their primary need, potentially positioning the US to compete with China in this regard. However, Coinbase might need regulatory approval for such a subversive mission.

Like HSBC, it is not that Coinbase does not know how to identify customer needs. It does not care to invest hands-on effort because its core business (in this case trading crypto where it is already legal) is going well enough.

Even within their core business, some fintechs shy away from the challenging task of comprehending customer needs. Onyx Private was launched in 2022 to provide digital private banking services akin to a "next-generation UBS" for young professionals. It has already announced a pivot from B2C to B2B:

He said Onyx will be shifting to a “B2B white-label platform-as-a-service model for community banks, regional banks, and credit unions” that want to launch digital apps built for young affluent consumers.

In other words: "While this UX failed to attract the target segment for our fintech, for your credit union, it would be a game-changer." If Onyx’s founders spent more time understanding the needs of young private banking customers, they would identify a craving for high-touch service. The point of "private" is to get a discerning hand-holding when getting investment advice or buying a Bentley, not just a posh-looking website.

Knowing End-User Needs is Not Always Critical

While understanding customer needs is critical in the direct-to-consumer sale of financial services and insurance, it could be ignored in some B2B2C use cases. For example, when a Life-Benefits-Retirement FSI sells its products to employers, the main contact tends to be the Head of HR. Does it matter that a typical Head of HR might not know how employees feel about their choices or the digital features? Often not. They might care more about the annual cost increases and breadth of HR and Benefits coverage from a single partner.

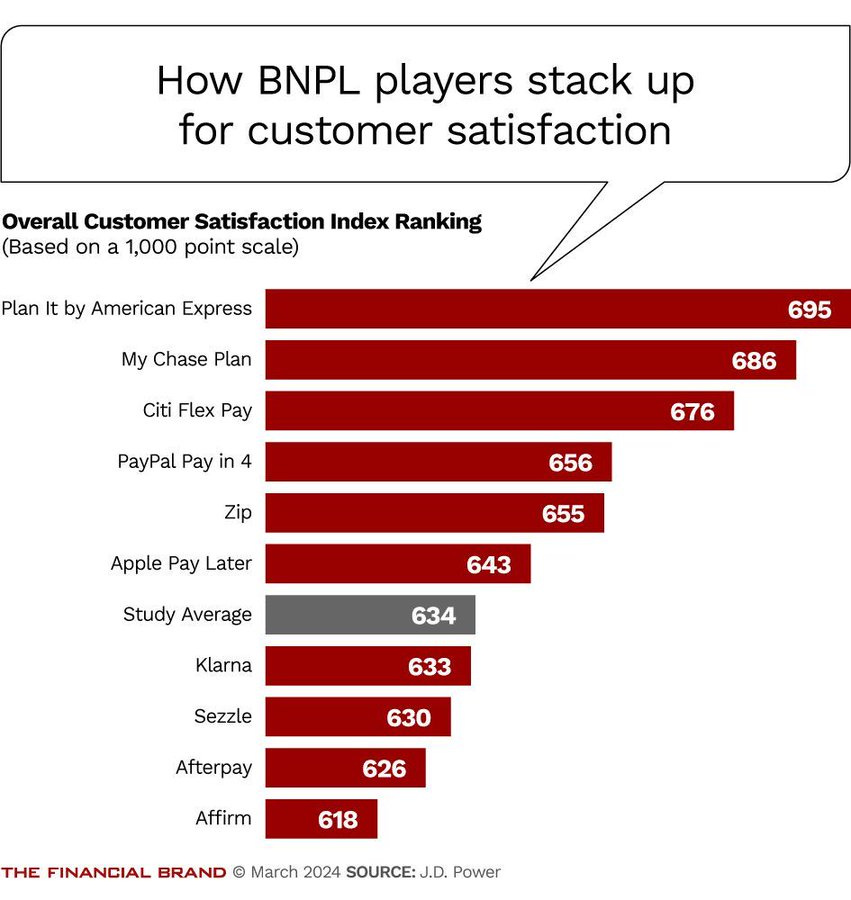

Similarly with some BNPL providers, in a recent customer satisfaction survey, incumbents received much higher marks than leading fintech companies. Even Citi was far ahead of globally renowned startups like Klarna and Affirm. How could this be?

For BNPL from Klarna and Affirm, the end-user could also be less critical than the decision maker who pays the bills, namely the executives of the retail partners. For American Express, customer satisfaction has to be higher because they pay for the service:

Data Monetization's ROI Hinges on FSIs Managing Three Types of Risks

When I worked with MasterCard in a developing market more than a decade ago, our CEO announced a $1 billion global target for data monetization. We were already selling some dashboards, but they offered little value. Banks and merchants wanted to know their share of spend and main competitors, ideally on the SKU level. That information would enable them to target the right customer with the right offer to ensure high relevance and ROI - a win for networks, banks, merchants, and customers!

The underlying technology to capture SKU-level information and present it as a compelling offer has been available since 2012. By now, most larger banks and fintechs have some Offers programs, but their impact remains minor. Merchants' card offers mostly benefit savvy consumers who would make the same purchase anyway. The trick for the offer platform is to persuade merchants that it is not the case. Why has there been so little progress?

A Single Customer Complaint Could Derail the Program

UX could be copied, technology bought, and talent poached, but data is the only sustainable moat for FSIs. Of course, extracting curated data from internal systems is a major challenge, especially if it involves cross-enterprise collaboration. It requires aligned incentives across the outgoing business unit, receiving business unit, and enterprise-level shared services (e.g., data management). However, proprietary data could be so valuable that even lower digital mature players like title insurers eventually figured out how to resell it:

This works unless customers realize that this data could be used against them and complain loudly. Sometimes, all it takes is one customer complaint and one article. General Motors recently stopped sharing its driving data with intermediaries LexisNexis and Verisk which re-sold it to P&C insurers for underwriting purposes. One Cadillac driver filed a lawsuit against GM and intermediaries when his insurance doubled. The New York Times wrote about it, and monetization was shut down. Earning low millions in a non-core business wasn’t worth the bad publicity.

FSIs Are Highly Selective About the Data They Share

Not just customers could be sensitive to how their personal information is used. JP Morgan recently sued TransUnion’s subsidiary, Argus, for using its data in the benchmarking product it sells to the bank’s competitors. Argus was collecting this data as a regulatory requirement on behalf of government agencies, and it appears it didn’t keep JP Morgan in the loop about the broader usage:

This is a common challenge for data monetization schemes dependent on broad industry participation. Top players are not necessarily averse to participation, but as long as use cases are explicitly defined and they share in the upside in proportion to their data contribution.

Regulators Favor Data That Reduces FSI Profits

And, of course, regulators don’t want FSIs to obtain more external data if it means new revenue streams or the possibility of higher prices for some consumers and businesses. Even in some developing markets more than a decade ago, Mastercard couldn’t get regulatory approval to share such data among willing banks and merchants. Regulators have only become more invasive since then.

The US's largest P&C insurer, State Farm, asked the California Department of Insurance to approve a 39% price hike for commercial apartments but was only allowed 23%. Already losing money, State Farm naturally announced a complete withdrawal from the state as a result, prompting this hilarious reaction from the state Insurance Commissioner, Ricardo Lara:

Lara said his plan also involves changing the models insurance companies use to better assess risk and to lower rates for those who protect their homes. "The current modeling is a black box," he said. "We're going to change that to be much more transparent."

If price controls don’t excite FSIs about working in California, perhaps disclosing their underwriting IP and interference with their models will. The bizarre goal of lowering rates when a carrier requests a 39% price hike prevents the Commissioner from considering which external data would help State Farm raise prices more precisely. On the contrary, in 2022, he warned carriers against using more data:

To be fair to financial and insurance oversight, this is a typical mindset of regulators in general. They start with the utopian objective of equity and dislike attempts to match consumer risk profiles with precise outcomes. For example, as the average high school student population was becoming less intelligent in the US, standardized tests were made easier and eventually disregarded to graduate almost all students. The mantra of all regulators seems to be: "Less Data, Less Problems," unless the data tracks compliance with regulations.

In Summary

The concerns about using customer data for monetization will continue to grow among customers, partners, and regulators. Successful FSIs follow the following five principles when setting up a new program:

Identify proprietary data and ballpark its value to ensure that monetization is worth the public relations and regulatory risks.

Receive explicit approval to use customer-identifiable data from customers and regulators.

Set up a separate operating unit responsible for data curation and selling in tight collaboration with the outgoing business line and enterprise data group.

Identify all allowable use cases with data buyers, align incentives with your data contribution versus peers (if relevant), and conduct regular audits.

Develop a communication strategy assuming monetization details become public.