How can FSIs Move from Digitization to Digital Transformation?

Five considerations for financial services and insurance companies to transition from traditional static operating models enabling only digitization to true digital transformation.

How can FSIs Move from Digitization to Digital Transformation?

"We have colossal tech debt, and our C-Suite disagrees on who should own the P&L, but at least our digital initiatives are going well," explained an executive from a $10B revenue FSI. I assured him that this is a typical state for an FSI, and as long as incumbents have comparable maturity and disruptors are small, this should be fine. Why risk transformation if everything seems to be okay with digitization? However, what if your FSI segment has one player rapidly capturing market share through advanced digital capabilities? How can you transition from a static operating model centered on digitization to a genuine digital transformation?

As we often discuss, the approach to digital transformation in FSIs has remained simple and singular for a decade, comprising of just three steps:

Step 1: The C-Suite and The Board collaborate to define the North Stars of digital transformation and outline the target state operating model.

Step 2: Each Line of Business (LOB) and Function are assessed for their current digital maturity and transformation velocity to identify any significant gaps.

Step 3: The Groups with the biggest gaps are confirmed to be led by individuals who are capable and willing to level up their operating muscles.

And here are just four slides that an FSI needs to complete these three steps:

Now, of course, in a typical FSI, most of the C-Suite executives and Board members understand only a portion of the above approach. They have been successful with entirely different frameworks and are not particularly interested in changing 'what works.' However, the same hypothetical FSI usually has a couple of executives who grasp all of these points and are willing to take some minimal career risk in order to try it out. The question remains: How do they start moving from traditional static operating models that enable only digitization when no one else is interested in true digital transformation?

1. Do not skip the steps

As individuals who are not CEOs or Board Chairmen of FSIs, we may lack the authority to steer the company ship and initiate a complete business and operating model transformation. Having served as a Board member and an advisor to C-Suites, I understand firsthand the frustration of witnessing decision-makers hesitating to embrace a proven approach, only to eventually come around years later. However, it is their responsibility, not ours. If they fail to recognize the need for transformation and prefer simple digital initiatives or superficial transformation efforts, our role is to provide them with more compelling information in the future or consider transitioning to another FSI with more forward-thinking leadership.

2. Time is on our side

The encouraging aspect is that time works in our favor. While there is a risk that certain FSIs might become complacent and fail to notice how their more advanced competitors or disruptors are gradually capturing 10% of their customers each year, eventually, most FSIs come to recognize the necessity of transformation. This realization may occur through existing leadership embracing the journey of leveling up or the transition to a new leadership team.

While digital transformation in FSIs is my passion, cross-border money transfer is my hobby. It has been enjoyable to observe the shifts in mindset among incumbents like Western Union and MoneyGram about disruptors like Wise and Remitly. The former have undergone the same three stages as most traditional FSIs in other verticals:

Dismiss: explaining that fintechs shouldn’t be taken seriously - “no volume” “big splash with their press releases” “can’t really be considered long-term players”

Digitize: spending 10-20% of the revenue on tech and consultants to automate and consolidate in order to create efficiency while doing digital PR

Transform: realizing that “something is rotten in the state of Denmark” and the fix has to come in the business and operating models

The only question is whether an FSI can reach stage 3 in time to fortify or, at the very least, salvage its franchise in a fierce battle, much like the ones Borders, Walmart, and IBM fought against various Amazon businesses, each with significantly different outcomes.

3. Discrimination is essential

As many FSIs sheepishly transitioned from equality-based to equity-based employee decisions while outsourcing management tasks to HR, it hindered the likelihood of digital transformation. Digital transformation offers an opportunity for everyone to level up (equality), but it also differentiates against individuals who may be incapable or unwilling to undertake the climb. This concept can be challenging to grasp since judgments are not solely based on current job performance but on an individual's potential to excel in a more demanding role in the future (qualification vs. capability). This discrimination manifests itself in three ways:

Certain groups receive significantly more budget and autonomy.

Some individuals receive higher compensation compared to their peers in similar roles.

Some people are let go from their positions despite possessing qualifications similar to their peers.

In our newsletter about the initiation of TD Canada's Personal Banking digital transformation, we highlighted that this specific line of business was given the green light to establish "a different kind of bank." Unlike its peer groups, this unit was granted the freedom to have fewer update meetings with enterprise management, more autonomy in making budget decisions, and the option to opt-out of enterprise-wide programs. Furthermore, TD Personal Banking had the authority to prompt some shared services groups to alter their operating models. The question arises: Who wouldn't want these privileges, and why was only this particular group granted such opportunities?

Despite some appearances, participating in digital transformation is not a perk that is unfairly bestowed on some employees. The process of engaging in business and personal transformation involves numerous failures, heightened stress levels, and requires investing extra hours. FSI executives should consistently remind all employees of these trade-offs.

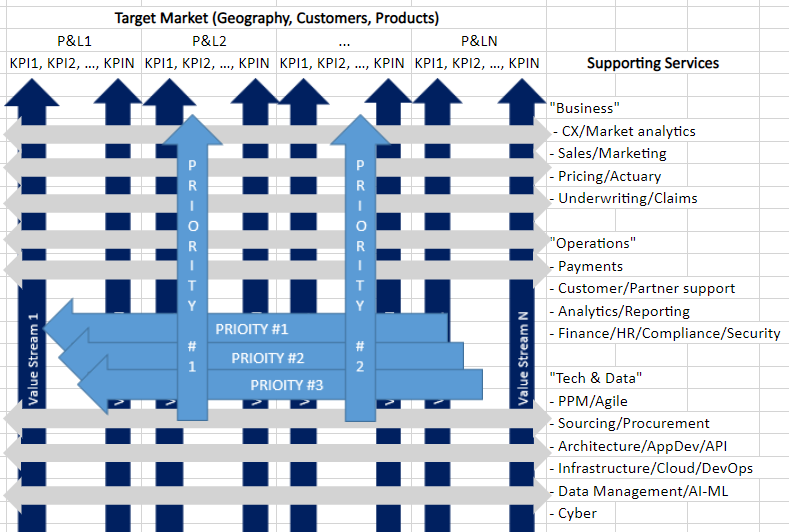

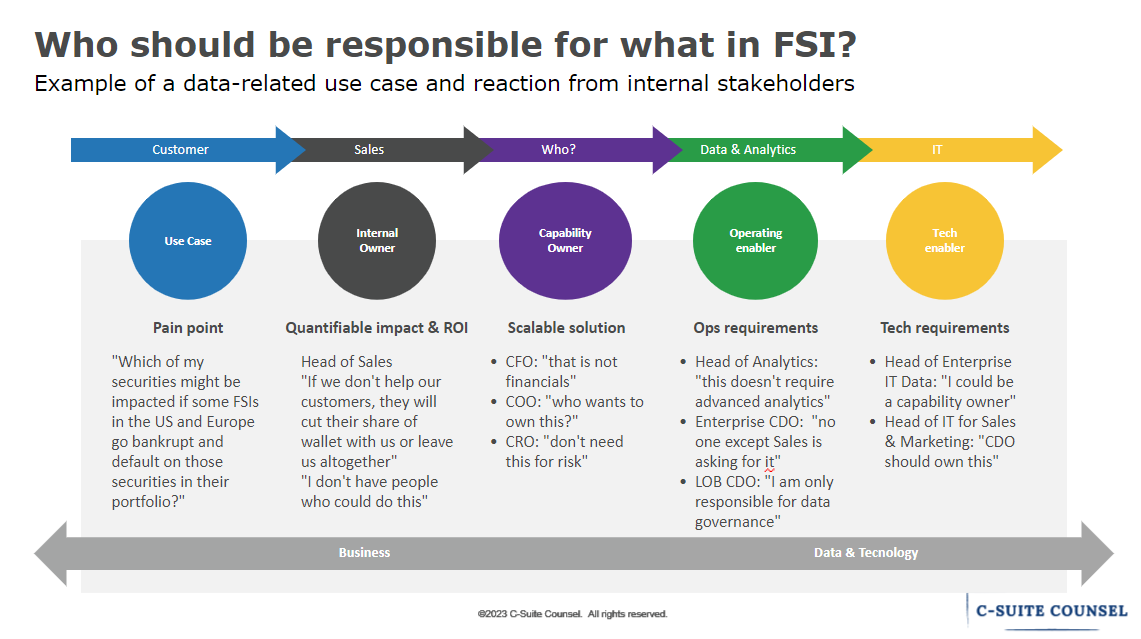

4. P&L vs. Support Function ownership

The culture of extreme ownership and the T-shaped employee profile are essential for digital transformation, but they can also be used as an excuse by some FSIs to evade clarifying groups' roles and responsibilities, particularly across enterprise, regional, and product teams. As we discussed in another newsletter, it falls upon the CEO to make those determinations, which may vary depending on the specific use case.

Since the P&L impact is the North Star of digital transformation, there should be a single owner for the P&L responsibility between product and regional groups. In countries like the US, a large FSI could have up to 10 product groups and another 10 regional groups, yet some FSIs have not fully determined how these groups should interact with each other. As a result, the P&L remains split, digital transformation is stalled, and there is an ongoing and unresolved debate on who should be supporting whom.

The decision framework for determining the right P&L ownership is based on which group exhibits higher digital maturity between products versus regions. In other words, the group that has progressed further in the digital transformation journey and can effectively capture the P&L impact should be granted P&L ownership. This approach ensures that if the supporting group fails to offer adequate support, the more digitally mature group possesses the capability to build some of that capacity, but not vice versa.

5. Annual revisit

When it comes to digital transformation, setting a target state for P&L ownership doesn't imply that all P&L assignments should be reconciled immediately. In a traditional FSI, not all Product or Regional groups are the same—some are top-notch, while others lag behind in digital capabilities. To proceed, begin with a full P&L assignment to the most advanced group and then gradually reconcile others as they become ready.

Since digital transformation is typically a multi-year journey, the question of which group to transform only needs to be discussed annually. This conversation spans both static and transforming groups. The transforming groups may realign with each other more frequently, typically on a quarterly basis. Presently, many FSI executives are evading these discussions in the absence of a CEO who is willing to lead an annual agreement to a logical conclusion (for more on the CEO role, refer to this newsletter).

This is the fundamental distinction from traditional re-organization in FSIs, which often results in exchanging one static model for another, leading to mostly failed outcomes. However, with digital transformation, as P&L groups and support functions evolve, their roles are dynamically adjusted toward the ultimate target state. Only when some groups begin to attain the target state of digital maturity, there is a semblance of organizational design stability. Nonetheless, for most FSIs, achieving this point is still a decade or more away. So the climb will seem indefinite, but the views will get increasingly gorgeous, and there will be rest stops along the way.

Other FSI Digital Transformation Reads

How Deutsche Bank’s 13-year attempt to kill off an IT system finally worked

Another great article on FSI. Concurring with your perspective, it’s absolutely vital for corporations to enlist the assistance of preeminent consultants to navigate the labyrinthine process of digital transformation. Executive compensation is inextricably tethered to a firm’s stock performance, thereby creating an intrinsic motivation to maintain a business environment characterized by dynamism and agility.

In this context, the calculus of cost becomes pivotal. Rather than viewing such transformations as financial burdens, they should be seen as strategic investments. Frequently, the financial implications of inertia—of failing to adapt or innovate—far exceed the expenditures associated with proactive, early-phase implementations.

It is essential, therefore, that firms adopt a far-sighted perspective, recognizing the latent value in investing in transformational efforts today to safeguard their competitive standing and financial health in the evolving market landscape of tomorrow.