Massive Technology Spend Can't Unburden FSIs of What Has Been

Also in this issue: What's Wrong with FSIs and Fintechs Expanding into Developed Financial Markets?

Massive Technology Spend Can't Unburden FSIs of What Has Been

"Our operating model is also siloed and opaque, but there is less backstabbing because executives are moved around more frequently. You need a couple of years of stability in a role before learning how to effectively sabotage your colleagues," a group of senior bankers who had worked at other large banks explained to me at an industry event last week. Hearing another round of horror stories about how leadership in different FSIs keeps making expensive decisions on launching new products, partnerships, or cost-cutting without cross-functional involvement led to my natural question to the group: which capabilities have improved in the last decade? The answer was always the same: technology.

After a decade of digital transformation attempts, FSIs seem to have learned the main lesson: when the operating model is ineffective, buy more technology. The hope is that by spending more on cloud, AI, digital tools, etc., front-line employees and their direct managers will collaborate productively while their executives can remain visionary idea generators who inspire and connect but don’t need to own leveling up. How is it working so far?

Technology spending in the range of 10-15% of revenue, once unheard of, is becoming the norm for top and regional banks in the US. For example, Key Bank is spending 13% of its revenue on technology this year. Its commitment to technology is so strong that the bank is cutting costs in other areas and risking the ire of analysts by driving overall expenses higher next year:

“… we took $400 million of expenses out last year just for the purpose of being able to invest in people and in technology and in the businesses that we're trying to grow… So expenses will go up in 2025, as you see the pull-through of the earnings that we're talking about, but we have not starved the business. We've continued to invest in our migration to the cloud. We've continued to spend $800 million a year in our tech area.”

Such a doubling-down on technology is especially puzzling since there are no signs that it has been driving significant business impact. Key Bank’s stock is trading at the same levels as three decades ago, and its revenue and profit have declined around 5% in the latest quarter.

The best example of an FSI with a disconnect between celebrating digital achievements while simultaneously facing declining revenues and profits is Bank of America. When its CEO famously declared in 2021 that “We're clearly a technology company,” he offered three reasons:

1. A large degree of sales comes from digital channels.

2. Many client-facing processes are digital.

3. Billions are being spent on technology annually.

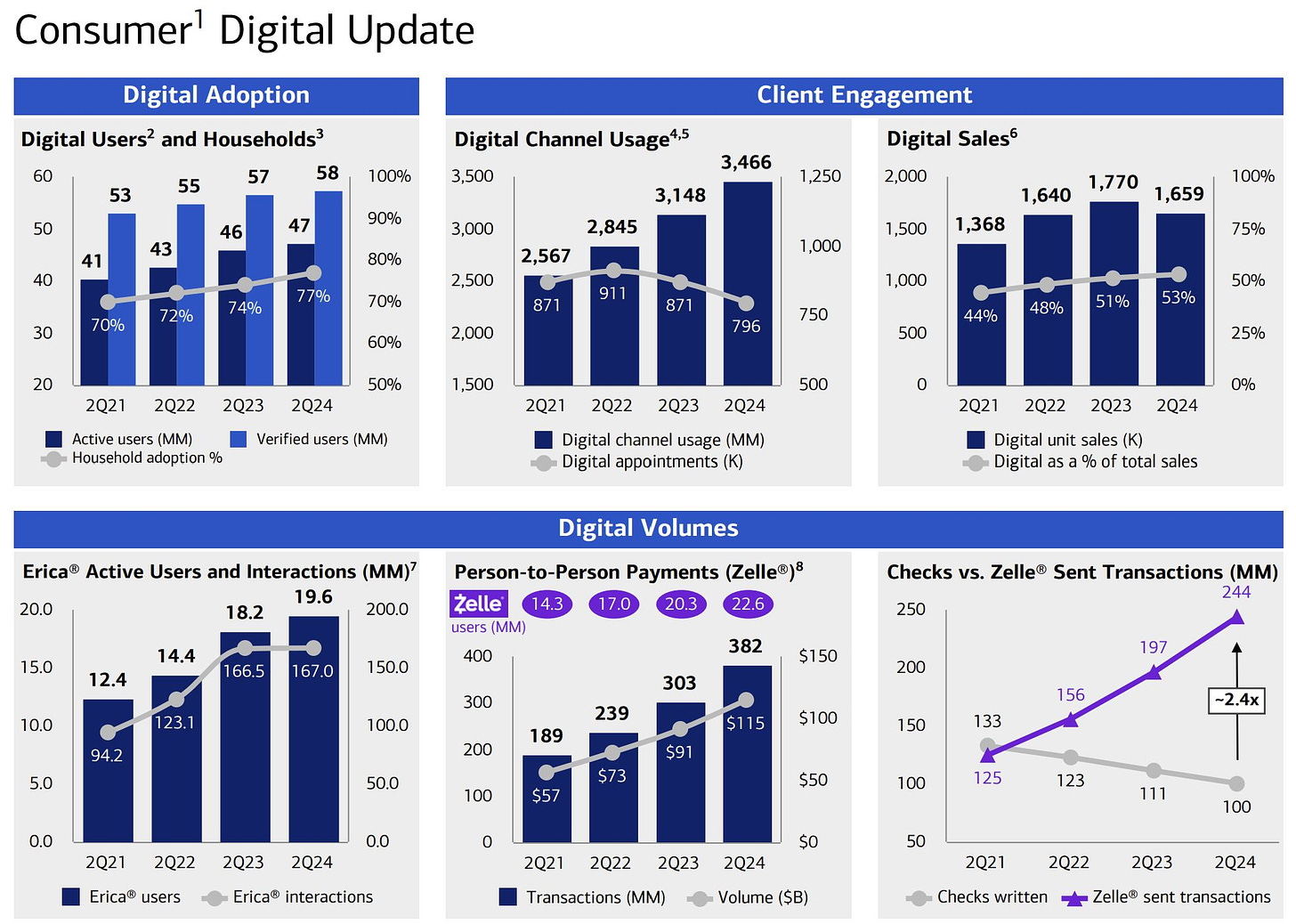

Indeed, those technology investments have created much higher digital engagement since 2021. However, even among digital achievements, there are troubling signs when it comes to Bank of America’s revenue-related indicators: both digital appointments and digital unit sales have been declining recently.

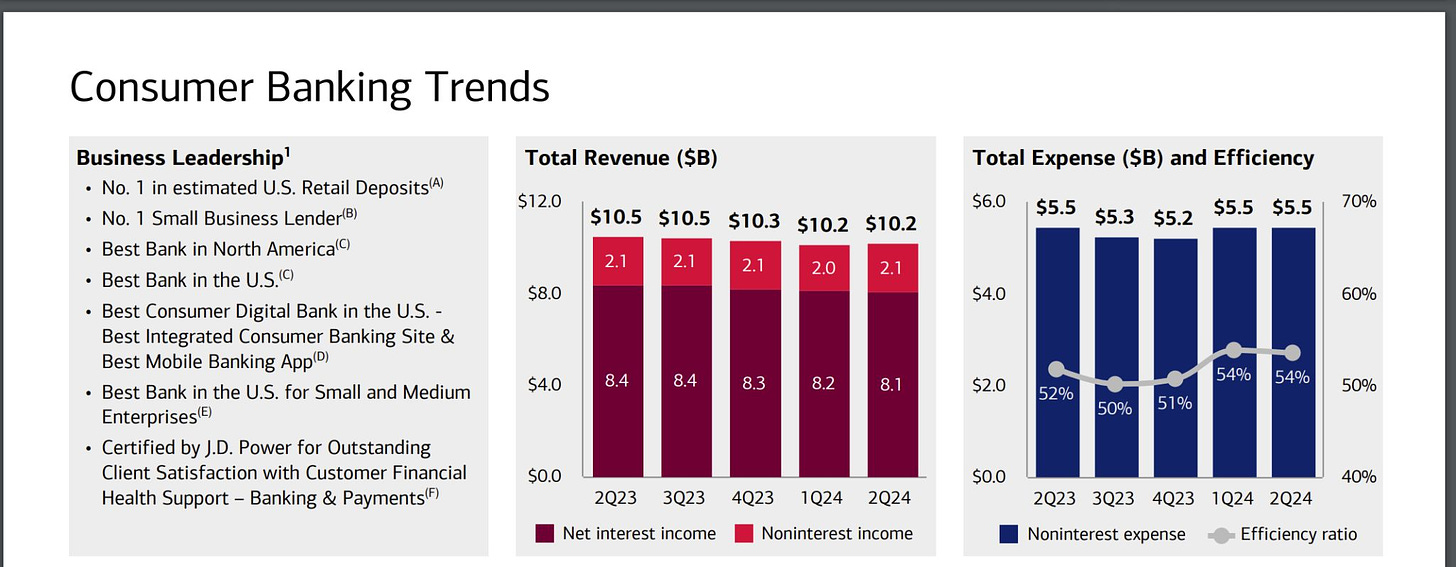

A decade ago, it might have been interesting to see digital channel adoption among existing customers, but in 2024, digital maturity only matters in the context of its P&L impact: new profitable customers and share of wallet/economics for existing ones. If Bank of America was a real technology company, its revenue and scalability would be exhibiting fast growth. However, for a traditional FSI, spending more than 10% of revenue on technology might earn accolades like the best consumer digital bank and best mobile banking app, yet still lead to declining revenues and a stagnant efficiency ratio:

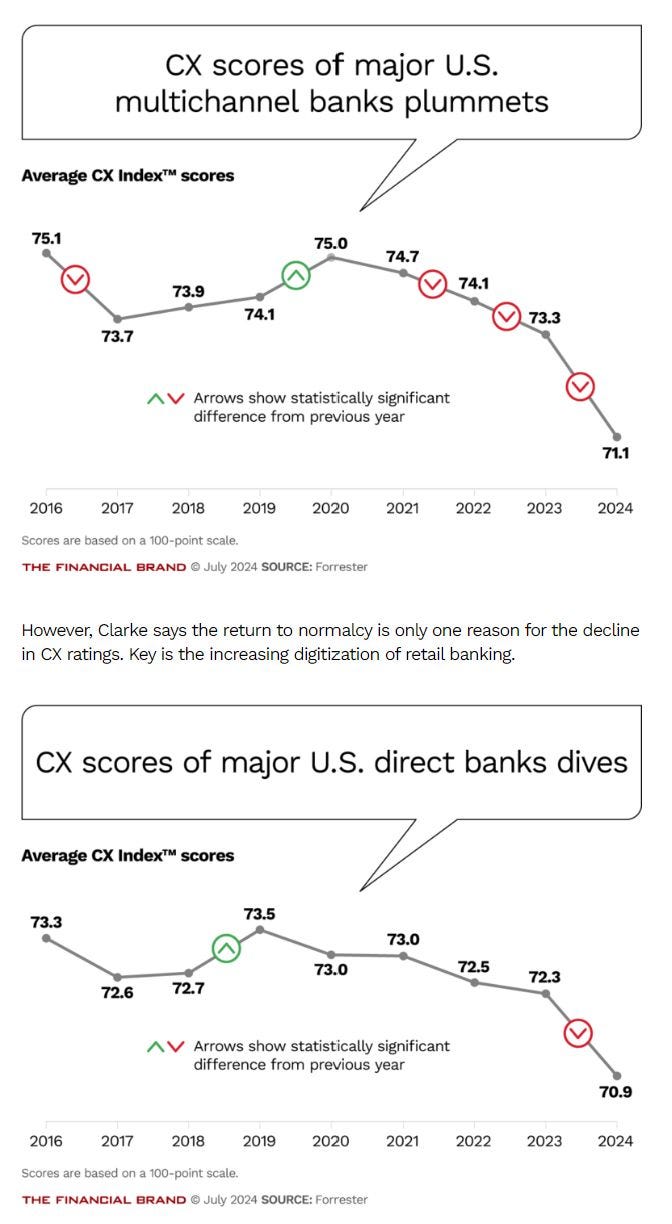

The most obvious illustration of the disconnect between higher technology spending and business impact is FSIs’ recent infatuation with chatbots. Somehow, executives were persuaded that AI and then Generative AI would make chatbots a better version of human agents while saving costs, and no amount of resulting customer complaints has shaken that hope so far. According to a recent Forrester report shared with The Financial Brand, customer experience at multichannel and direct banks has been declining for the last few years, with an acceleration in 2024:

Some FSIs already internalized that IT won’t miraculously fix gaps in their business and operating models. Until a year ago, Truist, the 6th largest US bank, was fully committed to the idea that higher technology spending creates lasting differentiation. However, because its CEO could never explain how that drives P&L impact, investors eventually lost patience, and the stock dropped almost 60% since its 2022 highs. The CEO had to announce $200 million in “tech optimization” and parted ways with the Chief Information Officer.

If we were to draw inspiration from one politician, we would say when it comes to a dysfunctional operating model, FSI leadership “got to take this stuff seriously, as seriously as they are because they have been forced to have taken this seriously.” Spending on technology is great for accelerating the passage of time but it won’t unburden what has been.

What's Wrong with FSIs and Fintechs Expanding into Developed Financial Markets?

Year after year, some incumbent FSIs and leading fintechs try expanding into the world’s most financially developed countries, only to shut those efforts down years later. What’s wrong with them acting like they just fell out of a coconut tree? When Chase launched its digital banking effort in the UK in 2021, I predicted a shutdown within three years. Little did I know that the bank would be okay with losing half a billion annually, with hopes of breaking even currently set for 2025.

Incumbent FSIs and leading fintechs’ massive cash cushions can enable years of attempts to generate positive unit economics before calling it quits. Cash App started its international expansion with the UK in 2018. It took the fintech six years to learn there are no P2P pain points in the UK, a realization that only seemed to occur after its founder, Jack Dorsey, returned to a hands-on leadership role.

Cash App UK to close on 15 September 2024… our strategic approach for Cash App, which prioritises our focus on the United States, and deprioritises global expansion.

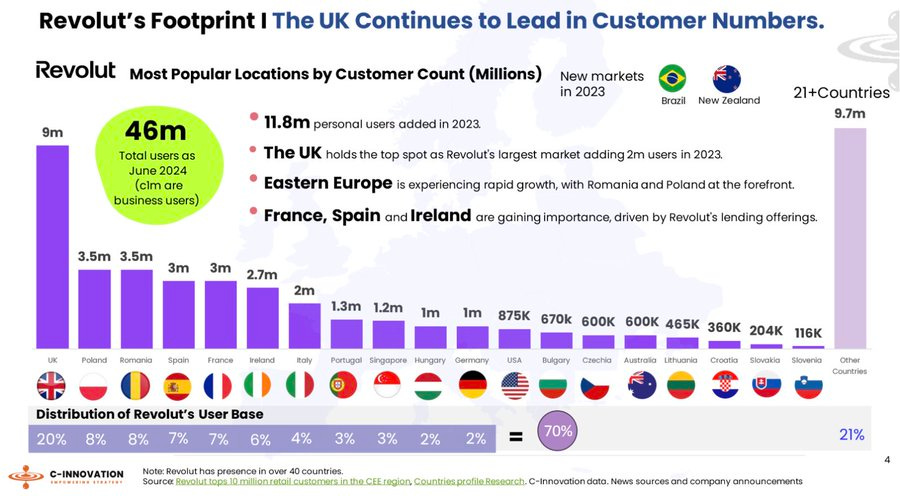

The same challenge is faced by UK neobanks like Monzo and Revolut as they try to gain a foothold in the US market. Monzo is currently gearing up for another re-entry after its first attempt failed. Revolut has gained close to a million customers but is struggling to identify a broader product-market fit. To explain why it has gained more clients in much smaller countries like Portugal or Hungary, Revolut cited two reasons: much higher competition in the US and surprise at how much Americans love credit cards.

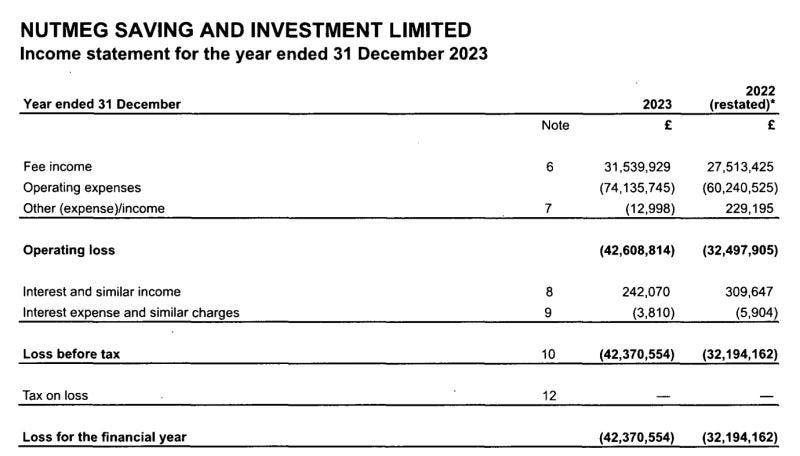

It might be tempting to expand into advanced financial markets via acquisition. In the same exuberant 2021, besides launching a digital bank in the UK, Chase spent around a billion dollars on buying the robo-advisor Nutmeg. The good news about Nutmeg compared to the bank’s internal effort is that it’s losing less money; the bad news is that it is losing money faster than it is growing revenue. In 2023, Nutmeg’s losses increased by 10 million pounds while revenue grew by only 5 million:

Besides the well-known mistake of buying companies at the peak of the business cycle, expanding into the world’s most developed financial markets undermines the basic premise of digital business. FSIs and fintechs can only generate significant positive ROI if they address pain points with new capabilities better than the competition. The chance for a new entrant to find sizable pain points and address them better than the myriad of local incumbents and fintechs might have had some validity a decade ago, but it’s highly unlikely since then.

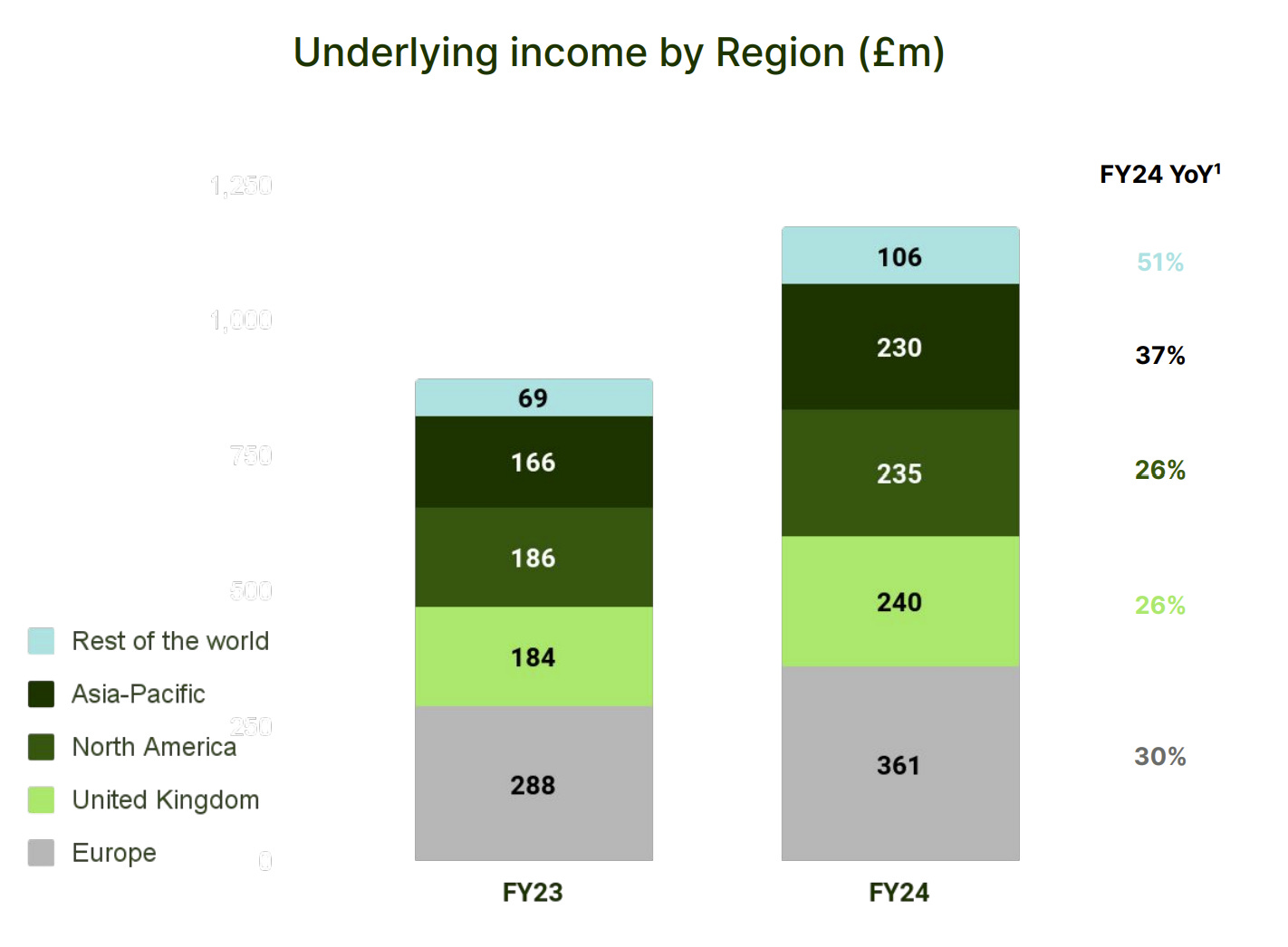

Success ideally requires a proverbial “10X” improvement in price and experience for upset customers compared to local competition. While not quite “10X,” Wise has developed a superior value proposition, offering cross-border money transfers at a fraction of the cost compared to US providers, with transfer speeds that are times faster. This has resulted in US revenue on par with Wise’s home base in the UK:

While expansion into less financially developed countries is also fraught with challenges, it is still more likely to generate ROI than targeting the most developed countries. Traditional FSIs and fintech must understand the context of the target market, the failure of those who came before it, and how it would do it much better.